Читать книгу The Less You Know The Sounder You Sleep - Juliet Butler, Juliet Butler - Страница 9

Оглавление‘One cannot hold on to power through terror alone. Lies are just as important.’

Josef Stalin, General Secretary of the Communist Party, 1922–53

Age 6

January 1956

Mummy

‘I’m bored,’ says Masha.

Mummy’s sitting by our cot, and she doesn’t look up from all her writing.

‘I’m really, really booored.’

‘You’re always bored, Masha. Play with Dasha.’

‘She’s booooring.’

‘No, I’m not,’ I say. ‘You’re boring.’

Masha sticks her tongue out at me. ‘You stink.’

‘Girls!’ Mummy puts down her pencil and stares at us over the bars, all cross.

We don’t say anything for a bit, while she goes back to writing. Skritch. Skritch.

‘Sing us the lullaby, Mummy – bye-oo bye-ooshki – sing that again,’ says Masha.

‘Not now.’

Skritch. Skritch.

‘What you writing, Mummy?’

‘None of your business, Masha.’

‘Yes, but what you writing?’

No answer.

Masha squashes her face through the bars of the cot. ‘When can we have those all-colours bricks back to play with? The all-colours ones?’

‘What’s the point of that, when Dasha builds them and you just knock them down?’ Mummy doesn’t even look up.

‘That’s because she likes building, and I like knocking.’

‘Exactly.’

‘Can I draw, then?’

‘You mean scribble.’

‘I can draw our Box, I can, and I can draw you with your stethoscope too.’

A bell rings from outside the door to our room, and Mummy closes her book. A bit of grey hair falls down so she pushes it behind her ear with her pencil.

‘Well, it’s five o’clock. Time for me to go home.’

‘Can we come home with you, Mummy?’ I say. ‘Can we? Now it’s five clock?’

‘No, Dashinka. How many times do I have to tell you that this hospital is your home.’

‘Is your home a hospital too? Another one?’

‘No. I live in a flat. Outside. You live in this cot, in a glass box, all safe and sound.’

‘But all children go home with their mummies, the nannies told us so.’

‘The nannies should talk less.’ She stands up. ‘You know exactly how lucky you are to be cared for and fed in here. Don’t you?’ We both nod. ‘Right, then.’ She gets up to kiss us on top of our heads. One kiss, two kisses. ‘Be good.’ I push my hand through the cot to hold on to her white coat, but she pulls it away all sharp, so I bang my wrist. I suck on where the bang is.

The door to the room opens. Boom.

‘Ah, here’s the cleaner,’ says Mummy, ‘she’ll be company for you. Tomorrow’s the weekend, so I’ll see you on Monday.’

She opens the glass door to our Box with a klyak, and then goes out of the door to our room, making another boom. We can hear the cleaner outside our Box, banging her bucket about, but we can’t see her through all the white swirls painted over the glass. When she comes into the Box to clean, we see it’s Nasty Nastya.

‘What are you looking so glum about?’ she says, splishing her mop in the water. She’s flipped her mask up because Nastya doesn’t care if we get her germs and die.

‘Mummy’s gone home all weekend, is what,’ says Masha, all low.

‘She’s not your yobinny mummy. Your mummy probably went mad as soon as she saw you two freaks. Or died giving birth to you. That there, who’s just left, is one of the staff. And you’re one of the sick. She works here, you morons. Mummy indeed …’

I put my hands over my ears.

‘She is our yobinny mummy!’ shouts Masha.

‘Don’t you swear at me, you little mutant, or I’ll knock you senseless with the sharp end of this mop!’ We go all crunched into the corner of the cot then, and don’t say anything else because she did really hit Masha once, and she cried for hours. And Nastya said she’d do something much much worse, if we told on her.

When she’s gone, we come out of the corner of the cot into the middle.

‘She is our mummy anyway,’ says Masha. ‘Nastya’s lying like mad, she is, because she’s mean.’

I sniff. ‘Of course she’s our mummy,’ I say.

Supper time and bedtime in the Box

Then one of our nannies comes into our room with our bucket of food. She puts it down with a clang on the floor outside the Box, and we both reach up with our noses, and smell to see what she’s brought. It’s our Guess-the-Food-and-Nanny game. We can’t see her, but the smell comes bouncing over the glass wall and into our noses, and it’s whoever guesses first.

‘Fish soup!’ Masha laughs. ‘And Aunty Dusya!’

I love it when Masha laughs; it comes bubbling up inside me and then I can’t stop laughing.

‘Fish soup it is, you little bed bugs,’ calls Aunty Dusya from outside the Box. Then she clicks open the glass door and comes in with our bowl, all smiling in her eyes.

‘Open up.’ We both put our heads between the bars with our mouths wide open, to get all the soup one by one spoonful each.

‘Nyet!! – she’s getting the fish eyes, I saw, I saw!’

‘Now hush, Masha – as if I pick out the nice bits for her.’

‘You do, you do – I can see, I can!’

‘Don’t be ridiculous.’ It’s hard to hear Aunty Dusya because she’s got her mask on, like everyone. Except Mummy, who’s got the same bugs as us. And Nastya, when she’s being mean. ‘And stop gobbling it down, Masha, like a starving orphan, or you’ll be sick again. Yolki palki! I don’t know any child at all for being sick as often as you. You’re as thin as a rat.’

‘I’m thinner than a rat,’ says Masha. ‘And Dasha’s fat as a fat fly, so I should get the popping eyes!’

I don’t know what a rat is. We don’t have them in our Box.

‘What’s a rat?’ I ask.

‘Oooh, it’s a little animal with a twitching nose and bright eyes, that always asks questions. Here’s your bread.’

‘I want white bread, not black bread,’ says Masha, taking it anyway.

‘You’ll be asking for caviar next. Be grateful for what you get.’ We’re always being told to be grateful. Every single day. Grateful is being thankful for being looked after all the time. ‘I’ll come back in half an hour to clean you up, and then lights out.’

Masha stuffs her bread into her mouth all in one, so her cheeks blow out, and looks up at the ceiling as she chews. We know all our nannies’ names off by heart. And all our cleaners’ too. And all our doctors’. Aunty Dusya says only special people can see us as we’re a Big Secret. She says it has it in black writing on the door. I don’t know why we’re a Big Secret. Maybe all children are Big Secrets? Masha doesn’t know either.

I love black bread because it’s soft and juicy, and fills me all up in my tummy. I have to stuff it all in my mouth, though, because if I didn’t, Masha would take it.

Aunty Dusya comes back to wash us after we’ve done a poo and a pee in our nappy, and gives us a nice new one.

‘I’m scared of the cockroaches, Aunty Dusya.’

‘Nonsense, Dashinka, there aren’t any cockroaches.’

‘Yes, there is!’ Masha shouts and points up. ‘See that crackle up there?’

‘Well, there is a small crack in the ceiling …’

‘That’s where they come out when it’s dark, and they go skittle-scuttle across the ceiling, then drop down with a plop on top of Dasha, and then they skittle-scuttle across her too, and she screams until I squish them and they go crunch.’

Aunty Dusya looks up at the crackle then, and picks up the stinky bag with our nappy in.

‘Well, we used to have cockroaches, once upon a time, when you were babies, but not now. There are no cockroaches in the Paediatric Institute. Nyet.’

She looks over at us, all cross and black, so I nod and nod like mad, and Masha pushes out her lip, like she does when she’s being told off, and twists the knot on our nappy with her fingers.

Then Aunty Dusya goes and leaves us alone, and the lights go off with a snap, and the door bangs shut with a boom.

I lie and listen hard, because when it’s dark is when they all come out.

‘I’ll squish them,’ says Masha in a hushy way. ‘You wake me and I’ll squish and squash and squelch them. I know all their names, I do … they’re scared of me … Yosha and Tosha and … Lyosha …’

After a bit I can feel she’s gone to sleep, but I can hear them all coming out and skittle-scuttling, so I reach out and hold her hand, which is all warm. Masha’s hand is always warm.

Having our heads shaved and dreaming on clouds

Skriip skriip. Aunty Dusya is doing Masha’s head with a long razor, and slapping her playfully when she wriggles. ‘Stop squirming, or I’ll slice your head right off!’

‘It hurts!’

‘It’ll hurt even more with no head, won’t it? Stop being so naughty! Dasha sits still for all her procedures, why can’t you?’

‘I’ll sit still,’ I say, quick as quick. ‘Do me. I like having my head razored. If we had hair, we’d get Eaten Alive by the tiny, white, jumpy cockroaches.’

‘Lice. That’s exactly right, Dashinka.’

‘But can you cut the top bit of my hair off too, and not leave this?’ I pull at the tuft they leave at the front.

‘You know we leave that to show you’re little girls, not little boys. You wouldn’t want anyone to think you were boys, now, would you?’

‘But everyone knows we’re little girls anyway. And Masha pulls mine when she’s cross.’

‘Like this,’ says Masha, and goes to pull it, but Aunty Dusya gives her another little slap and her mask goes all sucked into her mouth with breathing hard.

Dusya’s got a yellow something on today. I can see it peeking under the buttons of her white coat.

‘Why don’t we wear clothes like grown-ups? Do no children wear clothes?’ I ask.

‘Why would you need clothes, lying in a cot all day? Either that or in the laboratory … doctors need to see your bodies, don’t they? Besides, we need to keep changing your nappy because you leak; we can’t be undoing buckles and bows every five minutes.’ She pushes Masha flat on the plastic sheet of our cot, and starts on me. Skriip skriip. It tickles and I reach up to touch a bit of her yellow sleeve. It’s more like butter than egg yolk.

‘There. All done. Off you hop.’ We wiggle our bottom off the plastic sheet in our cot and she folds it up and then leaves us, wagging her head so her white cap bobbles.

‘Foo! Foo!’ Masha’s huffing and puffing because she’s got bits of cut hair in her nose, so I lean over and blow in her face, as close as I can get.

‘Get off!’ She slaps my nose.

‘You get off!’

‘No, you!’ We start slapping at each other, and kicking our legs until she gets hers caught between the bars and howls. Then we stop.

Saturdays are good, because we don’t have to shut off like we do when Doctor Alexeyeva comes in to take us into the Laboratory. But Saturdays are bad, too, because Mummy isn’t here and there’s nothing to do.

I hold my hand up and look through all my fingers. That makes the room seem broken and different, it’s the only way to make it change. I look at the whirly swirls of white paint on the glass walls of the box, then I look up at the cockroach crackle in the ceiling, and it breaks up into lots of crackles, then I look up at the strip light, and my fingers turn pink, then I look at the window to see what colour it is on the Outside now. Sometimes it’s black or grey or has loud drops or a rattly wind trying to get in and take us away. It’s blue today and I smile out at it, and wait to see if there’ll be a little puffy cloud. Mummy says there are lots of other buildings like ours on the Outside, but we can’t see anything ever. Just sky.

‘A bird!’ Masha’s been lying back, looking up at the window all the time. ‘Saw a bird! You didn’t!’

I didn’t, she’s right, but we both stare at the window and stare and stare, as they sometimes come in lots of them. But not this time. I stare until my eyes prickle. Then I see a cloud instead, which is even better – we imagine being inside clouds and on them and making them into shapes by patting them. And they move and change, like nothing in our Box ever does.

‘I’d sit on that one up there, see? That one, and I’d ride all the way round the world and back,’ I say.

‘I’d shake and shake mine,’ says Masha, ‘until it rained on everyone in the world.’

‘I’d jump right into it, and bounce and bounce, and then slide off the end, down into the sea with the fishes.’

When we do imaginings of being on the Outside we’re not stuck together like we are in the Box. In imaginings you can be anything you want.

Learning about being drowned and dead

‘Well, urodi. Here I am, like it or not.’ On Sundays, our cleaner is always Nastya. She’s got a nose like a potato, and hands so thick they look like feet. We must have done something very bad to make her so mean to us, but I can’t remember what, and Masha can’t as well.

‘Urgh. You should have been drowned at birth.’ She’s got the mop and is splishing the water over the floor again, banging the washy mop head into the corners. Shlup, shlup. I put my hands over my ears and nose, because I can’t shut off with her, like I can with Doctor Alexeyeva. Masha sucks all her fingers in her mouth.

‘Shouldn’t have been left for decent people to have to look at day in, day out …’ I can still hear Nastya through my hands ‘… and when the scientists have finished with you here, they’ll drown you, like kittens, and put you in a bag and bury you in a black hole, where you’ll never get fed or cleaned again.’ She makes a big cross on her chest with her fingers, which is what lots of the nannies do with us.

I won’t think of the black hole, I’ll think of the blue sky and bouncing on the clouds. I keep my hands over my ears and nose, so I don’t hear or smell anything, and close my eyes tight, so I don’t see anything as well. Except clouds in my imaginings.

When she’s gone, Masha starts pulling me round and round the cot, and I count the bars to see if they’re still the same as all the ones on my fingers and our two feet (not counting the foot on our leg at the back because the toes are all squished on that one). We only know up to the number five because Aunty Dusya told us years and years ago that we were five years old, just like there are five fingers on my open hand. Now we’re six, but I don’t know when that happened. Maybe it was when Mummy brought us the wind-up Jellyfish to play with? Mummy says we don’t need to learn how to count or read or write anything, because she’ll do it for us.

‘What’s drowned?’ says Masha, stopping going round and round for a bit.

‘I don’t know,’ I say. ‘But I think it makes you dead.’

‘What’s being made dead like?’

‘It’s like being in a black hole with nothing to eat.’

‘Let’s play Gastrics.’

‘Nyetooshki. I never get to put the tube down you.’

‘That’s because I’m always the Staff and you’re always the Sick. Here.’ She gets a pretend tube out. ‘Open up. Down we go.’ I open my mouth but I’m starting to bubble laugh, because she always puts her finger in my mouth pretending it’s the tube and wiggles it, and I bubble laugh before she even does it.

‘Molchee! Do as you’re told, young lady!’ she shouts, just like a nurse.

Then we both jump, as the door bangs open again.

‘Morning, my dollies! Now – what have I got for you today then?’

‘Aunty Shura!’ shouts Masha. Aunty Shura’s nice, too, so we can’t have done anything bad to her either. ‘It’s ground rice!’ says Masha pushing her nose in the air to catch the smell coming over the Box.

‘With butter!’ I shout, but I can’t smell it. I only hope it.

‘Yes, Dashinka, with butter,’ says Shura, and clicks open the door to the Box, carrying our bowl in her two hands.

She sits on a stool, and spoons a spoon of it into Masha’s open mouth, and a spoon into mine.

‘Foo! It stinks of bleach in here,’ she says, wrinkling her nose. ‘Nastya overdoing it again. Enough to drown a sailor.’

‘What’s drown?’ I ask, keeping the ground rice stuck in the top of my mouth, so I don’t lose the taste when it goes down in me.

‘Hmm, it means when you’re in water and can’t breathe air.’

‘Do you get dead when you can’t breathe air?’

‘Sometimes.’

‘What’s getting dead like?’

‘Goodness! What silly questions.’

‘Is it like being in a hole and hungry all the time?’ I ask.

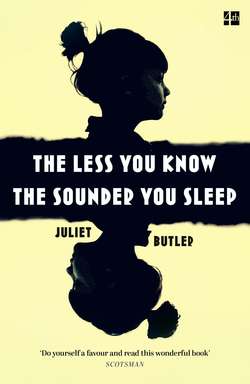

Her eyes crinkle up so I think she’s smiling, but I can’t see for sure under the mask. ‘Now, now. That’s quite enough. Mensha znaesh – krepcha speesh: the less you know, the sounder you sleep.’ It sounds like a lullaby, all shushy and soothing. And when she’s scraped the last little bit out of the bowl, she goes too. So we go back to crawling round the cot while I count off the bars on my fingers and toes.

Fighting to get single and then learning not to

‘Why have you got two legs all to yourself and we’ve got only one each, and an extra sticky-out one?’ I ask Aunty Shura, next time she comes in. But she pushes my hand away, because I’ve lifted up her skirt through the cot bars to see what’s there, and I can see, plain as plain, she’s got two legs all to herself.

‘Well I never!’

‘Why though?’ I ask. ‘Why?’

‘Because … well … because all children are born like you, with … one leg each …’ She pulls her mask up higher, then she loosens the laces on her cap and does them up again tighter.

‘So all children are born stuck together, like us?’

‘Yes, yes, Dashinka. They’re all born together …’

‘And then what happens?’

‘Then … they … ahh … become single. Like grown-ups …’

‘So, do we grow another leg each, when we get single?’

‘When do we get single?’ asks Masha, trying to pull herself up on the top cot bar. ‘When? When? When do we get single?’

‘Now then, you two Miss Clever Clogs, you know you’re not allowed to ask questions …’

‘But when? When do we get single?’ Masha asks again. ‘Tomorrow?’

Aunty Dusya looks all round the Box for something she must have lost, and doesn’t look anywhere at us. Then she goes out with a klyak of the glass door, without saying anything at all.

‘I want to get single now,’ says Masha crossly, and grabs with both her hands on to the bars. I can see the black in her eyes that gets there when she’s angry. She snatches my hand, and twists my fingers all back, and starts shouting: ‘I want to get single now! Go away! Urod! Get off me! Get off!’

I get scared as anything when Masha is angry. She kicks and scratches and punches and pinches, and I kick and scratch too, to keep her away. But I know it won’t make us get single.

‘Girls! Girls!’ After we’ve been fighting for hours and hours, Aunty Shura runs back in the Box, but she screams when she sees us, and I look, and see all red blood on us, but I keep kicking and punching to keep Masha away, and Shura runs out again.

She comes back with Mummy, who pulls at us both, and tells the nurse to tie us up to one and the other end of the cot with bandages. Masha hates being tied up all the time, so she starts shouting with bad, Nastya swear words, and so Mummy stuffs a bandage in her mouth too.

‘You two will kill yourselves if you carry on fighting like this,’ she says, leaning over us with her eyes all screwed up small and angry. ‘Do you understand? You’re black and blue from fighting all the time, but one day, one of you could die.’

She leans right into me then. ‘Do you want to die, Dasha?’

I shake my head. I really, really don’t want to die. I hate being hungry. And I hate the dark. So I decide then and there that I’ll do something which will make sure we never die.

I won’t ever, ever fight back again.

Looking out of the window to the real Outside

The next day Mummy comes back into the Box.

‘What you are, is bored,’ she says. She puts her notebook down on her chair. She’s with a nurse. ‘You need some fun.’

‘Oooh, can we have Jellyfish back?’ asks Masha, sitting up on one arm, with her mouth open. Jellyfish has gold and yellow and black and blue patches on his hard back, and lots of dangly legs, which rattle and shake when he’s wound up with the key. He makes a buzz, and trembles and we only had him for once. For one day. He’s loads and loads of fun.

‘No. You know you’re not allowed toys. That’s only for the filming. But I’ll tell you what: as a treat, I’ll let you look right down out of the window at Moscow. Now that you’re not in the Laboratory so much, you have nothing to do, day in, day out.’

And then she does this wonderful, wonderful thing.

She gets the nurse to push our cot right over to the side of the Box, which is by the wall. Right under the Window.

‘Now then. Hold on to the top bar of your cot and pull yourselves up.’ Our legs don’t stand by themselves, but our arms do, so we keep pulling and pushing until our chins and arms are on the bottom of the Window.

And then we look out and round and down and up, and we can see all of the Outside at once. I can’t think at all for looking and laughing.

‘Well?’ she asks. But we’re so bursting to happy bits with looking and laughing, we can’t talk. It’s full as full can be of new things, moving and happening.

‘Those grey blocks across there and all down the street are like our hospital block,’ says Mummy. ‘We’re six floors up here, which means six windows up from the street. The black holes are windows, like this one. The little black things moving down there on all the white snow are people. And the bigger black things, going faster, are cars carrying people inside them …’

I’m still so bursting inside with happy bits I can’t hardly hear her talking.

‘Those orange sparks come from the trams on the tramlines – they’re the black lines in the snow. The trams carry lots of people. And all the red banners up there on the buildings have slogans, which help people to work harder and be happier.’ I don’t know a lot of the words she’s saying, but I have no breath to ask.

One side of a block is all covered from top to bottom with the face of a giant man with kind eyes and a big moustache, which turns up at the ends, and makes him look like he’s smiling a big smile to go with his gold skin and gold sparkly buttons.

I point at him and look up at Mummy, but I still can’t talk.

She looks at the giant for a bit and then says, ‘That’s Stalin. Father Stalin. A great man. He’s dead now, but he will always live in our hearts. Just like Uncle Lenin.’

Questions we’re not allowed to ask about life on the Outside

‘Look! Look! That one’s fallen flat! Look! Haha!’

‘Where? Where?’

Masha’s pointing, and I’m looking and laughing too, but I can’t see it yet. There’s so much on the Outside, I need a hundred eyes or a hundred heads to even start seeing it all. ‘There! See the people trying to get him up. There!’ I follow her finger.

‘I can see! Haha! It’s the ice, Masha, they’re slipping on the ice because the snow’s melting, isn’t it, Mummy?’

I turn to her. She’s sitting behind us, writing in her notebook on her stool. She nods. We stay by the window all the time now, and it’s the best thing in the world. My head and eyes are all whizzing and whirring like Jellyfish legs, with all the things down there. Like fat green lorries full of soldiers who keep us all safe, but whose faces look like boiled eggs, looking out of the back, or children being pulled along by their mummies on trays, or packs of dogs, or lines of people waiting to get food from shops, or the clouds going on and on forever, getting smaller like beans, and the blocks going on and on forever, getting smaller too. And all watched by giant Father Stalin.

‘Why are some people allowed on the Outside and some aren’t?’ I ask after a long bit. ‘Like us?’

‘Because on the Out— I mean, out there, everyone is ordinary and you’re Special.’

‘When we get Single, will we be ordinary too?’ asks Masha.

‘What do you mean, “get single”?’ She stops writing and her eyes go small.

‘Aunty Shura said, when we grow up, we’ll get single and grow an extra leg each.’

‘Hmm. Aunty Shura should chatter less and work more,’ says Mummy, and makes a sniff as she rubs her nose. ‘Aunty Shura will get a talking to.’

‘Aunty Shura said all children are like us, but they’re not, see.’ She points at the street. ‘Not on the Outside, anyway, not even the baby ones.’

‘That’s quite enough of that. How many times have I told you not to listen to the nonsense your nannies talk, what with their prayers and their fantasies.’

We look back out again. I still don’t know why we’re Special. I hope it’s not nonsense that we’ll get single. I hope it’s true. I’ll go Outside then.

‘Can we see all the whole wide world from here?’ I ask.

‘No, Dasha,’ says Mummy. ‘I’ve told you before. This is only a small part of Moscow, which is the city where you live. I do wish you’d listen.’

‘Are there lots of cities? What happens when the city stops?’

‘Yes, there are lots of cities. And when it stops there’s grass and trees and a road, until you get to the next one.’

‘What’s grass and trees? Can you draw them for me?’ asks Masha. Mummy makes a whooshing with her mouth like when she’s tired or cross.

‘I really can’t draw everything, Masha. In fact, I can’t draw at all. I’m here to write. Why don’t you both try and stay quiet for five minutes?’

‘How long’s five minutes for?’ I ask.

‘Just please be quiet, and I’ll tell you when five minutes is up.’

I take a deep breath, to see if I can hold it for five minutes, and look straight at giant Father Stalin to help me. I hold my breath forever, but then it starts to snow and Masha laughs, so I do too, with a big sssshhhh as my breath blows out, and we pretend to reach our hands out and snap the fat flakes up as they bobble past our window. I’m getting lots of breaths in now, to make up for not having one for hours, and Masha looks round at Mummy.

‘Why can’t we go on the Outside too? Why are we in the Box all the time?’

‘Five minutes isn’t up,’ she says.

We wait again for more hours, and I hold my breath again, and count to five Jellyfish over and over, and then forget, because I keep seeing things, like how the snowflakes make the black clothes all white when they land on them.

I start breathing again, but I keep my mouth tight closed to stop all the questions spilling out. I don’t want Mummy to be cross with me, so I stuff them all in my head for later. Like, what sort of noise does snow make? How do the trams and cars move? Why can children smaller than us walk? I look up. And what does the sky smell like?

‘AAAKH!’ Masha screams all excited in my ear, so I scream too, and Mummy shouts crossly, and I start shouting, ‘What? What?’ until Masha points at a man who’s fallen under a tram. Everyone’s stopped in the snow to look and the tram’s stopped too, but then it goes on forward a bit, and the man is left squished in two pieces with all his red blood out on the snow.

‘He’s dead! He’s dead!’ shouts Masha, all excited as anything and laughing, and she jumps so much, we fall back into the cot.

‘And now you can stay there!’ says Mummy, and pulls the thick curtains closed, shutting the Outside all out.

‘Is he really dead, Mummy?’ I ask, panting.

‘No, no. He’s not. He’s just … ill.’ She peeks through the curtains.

‘Will the doctors mend him?’

‘Yes, Dasha. They’ll take him to hospital to be sewn together and made all better.’

‘But he’s in two bits. Can they sew two bits together?’

‘Yes.’ She doesn’t look up.

‘Will they take him to a hospital like ours?’

‘Well … a hospital for grown-ups, not children, but yes.’

‘Are we sewed together? Are we ill too? Is that why we’re in hospital?’ I ask.

‘Do stop asking questions, Dasha!’ Mummy stands up, picks up her pencil and notebook. She looks all tired and old. ‘You know it’s nyelzya. Not allowed.’

‘Nyelzya, nyelzya,’ mutters Masha. ‘Everything’s nyelzya.’

The door to our room opens then, and Mummy looks round to see who it is. She’s tall enough to see over the glass walls of our Box, but we can’t.

‘I don’t want to be ill!’ shouts Masha. ‘I’m not ill! I want to go on the Outside!’

‘Molchee!’ hisses Mummy.

‘I won’t be quiet! I yobinny won’t! I’ll run away I will, I want to be single like all the other people there on the Outside, I want—’ Mummy reaches down then, quick as quick, and slaps her hand over Masha’s mouth to stop all the shouting coming out, but it’s too late because the glass door opens and Doctor Alexeyeva walks in with the porter, the one who carries us in to the Laboratory.

We both get all crunched into the corner of the cot to hide when we see it’s Doctor Alexeyeva come in, and we start crying, because it means it’s time for our Procedures. Masha covers her face with her hands and I squeeze my fists tight and my eyes tight too, waiting, until I make everything go black and empty in my head.

February 1956

Leaving the Box

It’s sunny today and our cot is back in the middle of the Box, not over by the window any more.

Serves us right, said Mummy, for being so naughty. But it was Masha who was naughty … not me.

It’s worse, being back in the middle, than it was when we were always in the middle, because now I know the world’s happening through the window and I can’t get over there and see it happening. I can only do lots of imaginings about it in my head. But it’s not the same.

And I ache and ache, thinking that Mummy is cross with me, which is even worse than missing the world. I know it must have been Doctor Alexeyeva who got us back in the middle of the Box. I heard her shouting at Mummy, just before I switched myself off, saying me and Masha were being spoilt and treated like real children.

There’s a white patch of sunlight on the floor, which is moving. I can’t see it moving but when I close my eyes and count to five Jellyfish over and over again, for hours and hours, it’s hopped a tiny bit over when I open them again.

Masha’s asleep, but after a bit she wakes up and yawns.

She looks up at the ceiling and then at the window and then she asks me, ‘What did she mean when she said real children? Why aren’t we real?’

‘I don’t know, Mashinka. I asked Mummy, didn’t I? I asked why we’re not real, and she wouldn’t say.’

‘Why doesn’t anyone ever say anything? Why not?’ And then she starts hitting me and punching me and telling me to go away so she can be real like everyone else. But I don’t fight back any more. I just curl up small as a snowflake, until she gets too bored to keep hitting me. And then we both cry.

After a bit Masha goes back to sleep.

After a bit more, the door to our room opens.

‘Girls!’

It’s Mummy. Her voice is all high, instead of low like it normally is. ‘I have a wonderful surprise.’

Masha wakes up again, and does another big yawn as Mummy opens the glass door, klyak. She doesn’t have her notebook and pencil in her hands, she has clothes instead.

‘Nooka – I have these beautiful white blouses for you, see?’ She holds them up in front of us. ‘And a pair of trousers, specially tailored, just for you.’ She holds them up too.

Masha starts bobbing around all excited and smiley, and reaches out her hand to grab one.

‘That’s right, good, good, let’s get you all dressed up,’ says Mummy in the same high voice, like she’s not her, but someone else. I’m not as excited as Masha, because she really does sound like she’s someone else. ‘Look at the frills on the front, and the buttons. How many buttons, Dashinka?’ She holds out the blouse, so I take it.

It’s all soft, not like our nappy or our night sheet, which scrapes my skin.

‘Can I have a yellow blouse, not a white one?’ asks Masha, still bobbing around as she tries to get it on, but can’t, because she needs one arm to keep sitting up.

‘Of course not. Goodness, what a spoilt little princess you are.’ She turns away then, and has her back to us.

‘I’ll help then, Masha,’ I say. But I don’t know how to tie buttons up, so I pull through the bars to catch Mummy’s coat and get her to help. She turns round, but her nose is all red and her eyes are shining. It’s almost like she’s crying, like some of the nannies do when they see us for the first ever time. Sometimes they cry and cry and cross themselves and don’t stop forever. And Masha and me just watch them and don’t talk, but we sit there thinking it’s funny how some grown-ups cry even more than we do. Then she puts my blouse on too, and ties the buttons up. She tells us to lie flat and puts our legs in all the sleeves of the trousers, and ties them up at the front with two big buttons.

‘Well, well, yolki palki, you’ll look as pretty as two bridesmaids in this when you go to your new home. Yes, as pretty as two little—’

‘New home?’ I stare at her. ‘What new home?’

Masha stops playing with the frills and stares at her too. Then we both push ourselves away into the corner of our cot.

‘Don’t be silly. Nothing to be afraid of. Now then, are we all ready? The porter’s waiting to take you away.’

‘Porter?’

‘Away?’

‘Nyet!!’

‘We want to stay here!’

‘This is our home!’

‘You’re here.’

‘I’ll be good, Mummy!’

‘We won’t ask any more questions.’

‘Don’t let us go!’

‘When?’

‘Are you coming with us?’

‘MUMMEEEE!’

Masha and me are talking all over each other, but Mummy has her eyes closed and is shaking her head from side to side, and holding tight on to the top of our cot as if it’s going to roll away.

‘Stop this at once!’ She opens her eyes all of a snap, lets go of the cot and goes out of the Box to open the door to our room. ‘You may take them away now,’ she says. ‘They’re ready.’

A porter walks in, but not Doctor Alexeyeva’s one. He’s different. He smells different and has no mask but has a moustache like Father Stalin. But it’s not Father Stalin. This man doesn’t have kind, smiley eyes. He looks at us for a bit, then goes all yukky like he’s going to be sick. I feel like I’m going to be sick too.

‘Go away!’ shouts Masha as he bends to pick us up, and she starts hitting him with her fists.

‘Stop that at once, young lady, and do as you’re told!’ shouts Mummy. ‘Just do as you’re told! Do as you’re …’ she chokes, like she’s swallowed a fish bone, so Masha stops hitting him.

He smells like old mops as he lifts us out of the cot, but we have to hold him tight round the neck to stay on. We’re both scared as anything and crying.

Mummy kisses us both on the tops of our heads, like she does always, every night after she’s sung to us, and then she opens the door to the Box. Klyak. He pushes out through it sideways.

‘Nyyyyyyet!’ I’m holding his neck with one hand and leaning to Mummy with the other, I’m screaming for her to take me back. Masha’s doing the same.

The porter staggers a bit. ‘Hold still, you little fuckers, or I’ll drop you on your heads, and then you’ll be going nowhere!’

Then Mummy opens the door to our room as well, to let us out for the first time ever. She’s swallowing and coughing and her face is all blurry and wet. ‘I’ll visit you, girls. I’ll come and visit. I promise.’

‘Mummeeeee!’ I scream. ‘Mummeeee!’

She’s holding on to the door handle now, tight as tight, not saying anything. As he takes us away from her, I look at her over his shoulder, getting smaller as she stands in the door to our room, not moving to run and take us back. Until I can’t see her at all because of all the tears in my eyes.

Then I hear her voice. ‘You’ve got each other!’ she calls as we go through another door. ‘Always remember – you’ve got each other …’