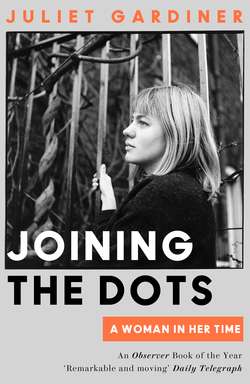

Читать книгу Joining the Dots: A Woman In Her Time - Juliet Gardiner, Juliet Gardiner - Страница 8

A War Baby

ОглавлениеAlthough this new era started in 1960, my life began on 24 June 1943, just before the end of the Second World War.

I was a war baby born on Midsummer’s Day. The previous week the RAF had mounted a major bombing raid on Düsseldorf, part of the sustained Allied attack on the Ruhr, Germany’s industrial heartland. Nevertheless, the end of the war in Europe was still almost two years distant, though the tide had begun to turn. At El Alamein, Montgomery’s Eighth Army had secured Britain’s first military victory, defeating Rommel’s Afrika Korps in November 1942. The surrender of all German troops in North Africa followed in May 1943. Alamein had led Churchill, desperate for a morale-raising British success, to venture, ‘This is not the end, it is not the beginning of the end, it is, perhaps the end of the beginning.’ His optimism seemed justified. By the summer of 1943 the Battle of the Atlantic was at last going the Allied way as well, with the ‘killer packs’ of German U-boats succeeding in sinking fewer Allied ships.

For those on the home front in Britain, however, the war remained unrelenting. Although the intense nine-month-long Blitz had ended in May 1941, frequent raids continued. One lunchtime in January 1943 a single 500kg Luftwaffe bomb was dropped on Sandhurst Road School in Catford, southeast London. Thirty-eight children and six teachers were killed in the so-called Terrorangriff (terror raid). There were rumours of deadly new secret weapons being developed by the Nazis. These would materialise the following summer as the lethal V1 ‘pilotless planes’ and V2 rocket bombs. Meanwhile rationing continued, and in many cases bit deeper.

It was a courageous and optimistic decision to have a baby at this moment. Apart from the practical difficulties of shortages of baby clothes, nappies, cots, prams, feeding bottles, teats and food, there was the uncertainty of bringing a child into a world when the map to the future had been torn up into jagged pieces. No one could know how long the fighting would go on, or what form it would take.

Shock and uncertainty about the future meant that the birth rate had fallen dramatically in the early months of the war. In 1941 it had reached the lowest point since records began: 13.9 per thousand of the population. When Peggie Phillips found out that she was pregnant in June 1941, she was pleased. But her husband, John, wrote from his army camp cautioning that ‘much as we would like another baby [they already had two daughters] these are hard times, and it would be wisdom to be brutal and cut off this little promise of a life until the world is a little more settled and we could find some sort of assurance that this new little person could be cared for in a decent way’.

This was the strongest argument, he suggested, ‘for you going to the osteopath [an abortionist] … Perhaps the most simple way of looking at it is that we ought to get rid of this “little accident” while it is early days yet and things haven’t gone too far: and we can always have the baby at another time (if it ever gets to be). I hate deciding the way I have.’

Mrs Phillips took her husband’s advice, raided the children’s saving accounts, and on the recommendation of a doctor ‘whose eyes she didn’t really trust’, travelled to a discreet nursing home in Kent where she paid fifty guineas for an illegal abortion. Sadly ‘another time’ never came, as John was killed in the battle of Monte Cassino later in the war.

Many other women had no choice but to be single mothers: they had been widowed by war. On the front page of The Times on the day of my birth, the list of those killed or missing in action is four times longer than the announcement of births. Some women had husbands, fiancés or boyfriends fighting abroad with no hope of home leave until the war was over.

After 1941 the birth rate rose steadily, however. Even in such an unpredictable world there were clearly many who wanted to lay down a marker for the future; to normalise the conventional progress of family life in the midst of chaos, anxiety and despair. Biological clocks ticked louder and youngest children grew older, as did their parents. War was not going to be outwitted, it had to be endured. Life, as usual, had to ‘go on’ and be celebrated in as many ways as possible.

Of course, as an infant I was unaware of the turbulent times into which I had been born. As I slept soundly in a second-hand Silver Cross carriage pram, under an apple tree at the end of the garden, the nation was gripped with the excitement and optimism that accompanied the news of the successful D-Day landings on 6 June 1944; I had no idea of the terror induced by the buzz bombs and V2 rockets that devastated London and parts of the home counties in the following months. Walking by the time VE Day was celebrated on 8 May 1945, I was still unlikely to have been perched in a high chair to tuck into jam sandwiches or trifle at a Victory in Europe street party. This was partly because of my young age, but also because on the whole the home counties did not go in for that kind of communal merriment.

For us there was rarely bunting and flag-waving, and we never dragged a piano into the street so that neighbours could gather round the old joanna and have a rousing sing-song. So often the most potent images of civilian war are of the urban working classes: sheltering in the Underground, emerging from their bomb-battered houses clutching all they could carry of their meagre possessions, waving Union Jacks outside Buckingham Palace or splashing in municipal fountains on VE Day. It was the working classes (some seventy per cent of the population, if assessed by the indices of unskilled or semi-skilled employment) who became the public face of the civilian war.

The middle and lower-middle classes fought a more private war. They were less likely to be found in public air-raid shelters, under archways or down the Tube. They sought protection in Anderson shelters in their own gardens or evacuated themselves as well as their children to safer places in the country or abroad. Celebrations were less exuberant and more self-contained: a glass of Bristol Cream sherry with a few close friends in the front room rather than beer or ginger pop in the street.

‘The day we have waited for for nearly six years, and at last it is here, it is miraculous, exciting, wonderful,’ wrote Madge Martin, the wife of an Oxford vicar, on VE Day. ‘Lovely weather, streets beflagged, happy crowds dancing in the streets, singing everywhere, infectious happiness … packed churches, thankful people.’ She invited a few friends and neighbours into the vicarage, where

we listened to Churchill speak in the afternoon, quietly, no boasting. The King spoke at 9 p.m. We listened to his modest speech and drank sherry happily and rather dazedly … before going out to see the sights … enormous crowds shouting, cheering, dancing, huge bonfires fed by ARP properties, magnesium bombs, great logs of old chairs, tables, ladders etc. with dancing rings of young people circling them, beautiful floodlit buildings, lighted windows, torchlight processions and a good humoured gaiety with no rowdyism … Robert [her husband] and I went about together happier than for years remembering it all for ever. Light after darkness. Thank God for this day of days.

I Don’t You Know There’s a Peace On?

Whatever a person’s class, the dolorous grey cloud of postwar austerity hung over the whole country within days of the end of the war. The wartime excuse for shortages, regulations and bureaucratic inefficiencies – ‘Don’t you know there’s a war on?’ – was inverted almost as soon as the VE Day celebrations were over, the bonfires damped down, the children’s street parties cleared away. ‘Don’t you know there’s a peace on?’ became the ironic, resigned, sometimes bitter question in those early postwar months – one that particularly affected women. Rationing persisted until 1954 when meat was finally taken ‘off the coupon’, and in many cases shortages were more acute than during the war. It was estimated that housewives spent an average of at least an hour every weekday in a queue. Grocers’ shelves were half empty; bread, which had never been rationed during the war, was limited to two large loaves a week of unappetising grey bread adulterated with a high chalk content and, consumers suspected, cattle feed. Strange new products were imported such as blubbery whale meat (advertised as being like steak but in fact with a fishy aftertaste) and barracuda fish, known as Snoek, that no one wanted to eat despite exhortations to mash it with chopped-up spring onions and serve it on toast, so it was eventually fed to cats, some domestic, some feral, living in roaming posses on bomb sites.

Manufacturers with nothing to sell valiantly tried to keep their brand names in the public eye for the day when they did. ‘Won’t it be nice when we have lovely lingerie, and Lux to look after our pretty things? Remember how pure, safe Lux [soap flakes] preserved the beauty of delicate fabrics?’; ‘Soon all Heinz 57 varieties will be coming back into the shops, one by one’; ‘Unfortunately, Cadburys are only allowed the milk to make an extremely small quantity of chocolate … so if you are lucky enough to get some, do save it for the children …’

The 1946 exhibition Britain Can Make It, staged at the Victoria and Albert Museum – the windows of which had been blown out by bomb blast, hastily replaced by requisitioning all glass production for the purpose – was designed to show that the country could again establish itself as a manufacturing nation, turning swords into ploughshares, or rather Spitfire parts into ashtrays. But though one and a half million people flocked from all over Britain to queue for a glimpse of the phoenix rising, the exhibition was soon wryly mocked as ‘But Britain Can’t Have It’ since most British production went for export to repay the staggering debt of $3.7 billion that the country owed to the United States. As Mollie Panter-Downes, London correspondent of the New Yorker, wrote, ‘the factories which people hoped would soon be changing over to the production of goods for the shabby, short-of-everything home consumers, are having to produce goods for export. The government will have to face up to the job of convincing the country that controls and hardships are as necessarily a part of a bankrupt peace as they were of a desperate war.’

The ambivalent adjustment to peace could be seen in the faces of the demobilised fighting men, as they exchanged their khaki or blue uniforms for ill-fitting suits. Many of the jobs they’d left when call-up papers arrived had disappeared, despite promises they would be kept open for them when they returned from the war. The workplace had changed, new skills were needed, and the colleagues who’d remained at home had overtaken them. Many women, while thankful to have husbands home again, were uneasy about having to relinquish the head-of-household role they’d been obliged to assume and to have their decisions questioned, their independence compromised. Those women who would have liked to continue to work outside the home found formidable barriers in the way: priority was given to men when it came to job vacancies; the nurseries set up during the war to enable women to work were peremptorily closed down, like theatre cloakrooms when the performance was over.

In addition, husbands often disapproved of their wives working, and a slew of childcare ‘experts’ pronounced on the damaging effects of maternal deprivation, insisting that mothers should remain at home, nurturing, caring. It was a measure of the largely unwelcome return to pre-war convention that women who had driven ambulances, heavy lorries and jeeps during the war were not expected to get behind the steering wheel of the family car. Fathers drove while their wives sat in the passenger seat, forced to read the map and give their husbands directions.

Both women and men came to miss the unexpected pleasures of war: the intense ‘live now for today for tomorrow you may die’ mentality that had led to transitory passions and fleeting, often illicit, affairs. Women yearned for the near-Hollywood glamour that one and a half million GIs from the United States had brought to Britain from 1942 until the attack on ‘Fortress Europe’ on D Day. They missed the catchy, energetic beat of the imported American music and the invitations to US bases where, with any luck, Glenn Miller might be leading his orchestra on the trombone. Those dances – the Lindy Hops and Jitterbug Jives – were a world away from the sedate waltzes and foxtrots of formal occasions, or the jolly, communal country dancing in village halls up and down Britain.

As the euphoria of victory flattened, diarist Madge Martin felt guilty that though she dutifully attended the harvest festival in her husband’s church, she found no pleasure in the display of nature’s mellow bounty.

In Barrow-in-Furness in northwest England, the middle-aged Nella Last, who had found a new confidence and purpose in her wartime work with the Women’s Voluntary Service, wondered what she could do now that there was no need to raise money for the war effort, serve tea and buns to war workers, or provide clothes and comforts for the troops and refugees. Was her life to revert to looking after her uncommunicative, stick-in the-mud husband, tending her garden, and polishing the brass ornaments in her house until they gleamed?

II A Child’s War

As a small child I of course had no reference point for pre-war or for the war. I missed neither white bread nor the choice of shampoos. I presumed that it was normal to carry, snail-like, an edited version of your home around with you, taking aspirins and sticking plasters in a sponge bag; cotton, needles, matches, batteries and string in an empty waxed cardboard Meltis Fruit Jellies box, in case these were unobtainable on your travels.

Hertfordshire, the county in which I was brought up, had been designated a ‘neutral’ area during the war, one that neither sent nor received evacuees under the official government scheme, though of course many private arrangements were made ‘to get the children away’ from designated danger zones. Some stray bombs had fallen not far from my home, evidenced by craters in the roads or fields, some of which were absorbed into the landscape as ponds. By the time I was born, virtually no one carried a gas mask anymore and the Anderson shelters were gradually colonised by weeds and brambles.

I had few toys and those I had were invariably hand-me-downs from my parents and often incomplete: lead farm animals with matchsticks for legs, Dinky cars with a wheel missing. A home-made stockinet rabbit I called Tipsy was a particular companion that I pushed around in a wooden box on wheels for a pram. But I was not aware of the absence of the playthings that might have filled a middle-class child’s toy cupboard in the 1930s.

There are a few reminders of war, however, that I do recall from those early postwar years. One was the evidence of destruction on trips to London, when my mother and I went shopping or visited the Wallace Collection at Hertford House, which was my mother’s favourite cultural venue. She loved the domestic interiors by Dutch and Flemish artists such as Vermeer and Pieter de Hooch and found it convenient that it was just round the corner from Selfridges, and a couple of bus stops away from Daniel Neal’s in Kensington for Start-rite shoes, liberty bodices, fawn knee socks and navy knickers for me.

Nothing was whole anymore, or so it seemed. Many buildings were nothing but facades; others had tarpaulins stretched and lashed down to serve as roofs; windows were boarded up, or just left as holes in the brickwork. There were sudden gaps in terraces of houses or parades of shops. Stretches of Oxford Street were like a Wild West boardwalk, and looking in the windows of John Lewis’s department store which had been all but razed to the ground on 18 September 1940 was like peering into an aquarium: a narrow rectangle of glass behind which whatever paucity of merchandise was available could be glimpsed. In February 1946, Vogue was thrilled to report that ‘Dickins & Jones [in Regent Street] are soon to have their plate-glass windows restored,’ although what would be displayed in them was anyone’s guess.

Rationing affected me consciously not at all. I had no pre-war abundance with which to compare the shortages, so the leather-hard liver (offal was not rationed), the tasteless mince eked out in a sea of imperfectly mashed lumpy potatoes, the slightly muddy, undersized carrots from the garden, were what I expected to be served – and was. I was unquestioning of the eggs stored in isinglass (made from fish bladder) in the larder; oblivious to the fuss made when the import of dried eggs from the US was temporarily banned; non-complicit in the illegal acquisition of butter and cream from a local farmer. It was not until sweets came ‘off the coupon’ in 1949, only to go straight back on again since the demand was so heavy it could not be satisfied, that rationing impacted on me. I had spotted something I liked and pointed to it, only to discover that chewing gum was not the nougat I had imagined it to be.

The other subtler memory is of class, which I could neither conceptualise nor name as such at the time. I recall very well the gossip that I would later recognise as disquiet that class, and thus power relations, had been turned upside down during the war – and the implacable determination to set them to rights again. In my mother’s view – and she was not alone in this – shopkeepers had become very ‘uppity’, reserving special goods on points, keeping the occasional few oranges under the counter for favoured customers. Such retailers seemed to regard the long queues that formed outside shops as their personal supplicants. The grocer who weighed out sugar in blue paper bags, scooped biscuits from glass-topped tins, sent his delivery boy round weekly on his bicycle with my mother’s order of rashers of streaky bacon and a box of Post Toasties cereal, must have realised that as ration books disappeared, his control was ebbing. The customer was again king (or rather queen) and had a choice of shops to patronise. The half-crown or capitalist ten-shilling note became the only currency of exchange required, instead of the government-issued ration book to be stamped.

Herbie Gates was one of the church wardens at St Mary’s Church, Hemel Hempstead, where my mother went to matins every Sunday and was a member of the Mothers’ Union. Before the war he had sometimes helped with the heavy work in our garden, but during the war he had volunteered for Civil Defence duties, becoming an ARP warden, a responsibility he had taken very seriously, even officiously. ‘Little ’itler’ was murmured as he admonished ‘Put out that light!’ to householders demonstrating inadequately observed blackout. Now that he had handed back his brassard and tin hat, he too must be cut down to size, according to my mother and her neighbours, and put to setting potatoes, scything nettles and taking the church collection plate again, rather than having his wartime authority recognised as was surely his due.

It is not surprising that I have no memory of the war or its immediate aftermath, but what is surprising is that while I could read the signifiers of shortages and destruction, I had almost no factual knowledge until I was almost an adult about this cataclysmic event that would slice the twentieth century in two. No one I knew wanted to talk about the war that had gone on too long and too painfully and had put lives on hold for half a generation. There was no narrative of the war, though it was proffered as an explanation for many things, including the appearance one Sunday lunchtime of a neighbour who had been in a Japanese POW camp for three years, crawling on his stomach through the open French windows of his family home some months after his release, a knife clenched between his teeth as he threatened his wife and children.

Boys played cowboys and Indians, not Tommies and Nazis; we looked at maps of the British Empire in primary school, not the world at war. The Second World War was not on the syllabus at secondary school either, and nor was it offered as a topic when, much later, I went to read history at university.

There were soon plenty of books about the military aspects of war: battles, generals’ memoirs, discussions of causes, strategies and hardware. Cinema-goers too thrilled in time to such heroic films as The Wooden Horse and The Dam Busters. But the civilian experience remained largely unspoken. During the war, films such as Waterloo Road, Millions Like Us, Went the Day Well? and Mrs Miniver had filled cinemas with their subtle – and sometimes not so subtle – messages of propaganda and encouragement for the home front. Give your all for the war effort; pull together for victory; keep faithful and devote your energies to keeping your home happy and secure for when your fighting man returns. Immediately after the war, the dreariness of wartime sacrifice was not what cinema-goers wanted to be reminded of; the films they flocked to see were comedies, musicals, historical dramas and thrillers.

Richard Titmuss’s volume of the official history of the civilian war, Problems of Social Policy, came out in 1950 but it was not until the late 1960s that books for the general reader began to be published. Angus Calder’s The People’s War, the first – and to date the best – book on the civilian war in Britain, much influenced by Titmuss, was published in 1969, followed in 1971 by Norman Longmate’s history of everyday life in wartime Britain, How We Lived Then. The first of the twenty-six episodes of the epic series The World at War directed by Jeremy Isaacs was shown on ITV in October 1973. ‘Home Fires Burning: Britain’, the single episode on the civilian side of the war, written by Angus Calder, was transmitted on 13 February 1974.

There were many hard-working and courageous women who joined the forces in the war and gradually the great value of the Auxiliary Territorial Service (ATS), the Women’s Royal Naval Service (WRNS), the First Aid Nursing Yeomanry (FANYs), the Women’s Auxiliary Air Force (WAAFs) and the Women’s Land Army (WLA) was recognised, as was the story of the heroic women recruits to the SOE (Special Operations Executive). However, the contribution of women on the home front was slower to be acknowledged. This was in no way solely a women’s domain: think firefighters, Civil Defence and Observer Corps, medical staff and many more organisations which in most cases consisted of more men than women. Nonetheless, women did ‘keep the home fires burning’, in their own houses if their meagre coal rations stretched to it, but also on the land, in banks and offices, in munitions and aircraft factories, on buses, in postal services, as porters at railway stations, and in welfare and medical services.

Statues of Second World War generals and leaders strut on plinths throughout the country. Even the animals – horses, dogs, pigeons, mules – who served in various ways in wars had a monument erected at the edge of Hyde Park in 2004. But it was not until nearly a year later that a sombre bronze monument depicting the wartime uniforms women had worn, both military and civilian, hanging, discarded, from hooks, was unveiled in Whitehall close to the Cenotaph. Certainly I had no idea in those early postwar years of the professionalism and heroism that must have been displayed by the women around me. It was many years later, through my work as a historian, that I came to understand the texture of that time.