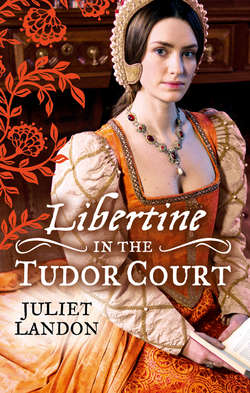

Читать книгу LIBERTINE in the Tudor Court: One Night in Paradise / A Most Unseemly Summer - Juliet Landon - Страница 7

Chapter One

Оглавление23 June 1575, Richmond, Surrey

A dorna Pickering’s ability to stay calm in the face of adversity was put severely to the test the day that Queen Elizabeth went hawking. They were in the park at Richmond and Adorna was noticed not so much for her superb horsemanship but for her graceful fall backwards into the River Thames and for her pretence that it was nothing, really. Though Adorna managed to impress the Queen, there was one who refused to be impressed in quite the same sympathetic manner.

It had all begun so well, the midsummer sun promising a windless day perfect for hawking, one of Her Majesty’s favourite sports in which she always indulged when staying at her palace in Richmond. The park was extensive, well stocked with deer and water-birds, and a select gathering of the Queen’s favourite courtiers made a brilliant splash of colour behind her, quietly vying with each other to show off their finery, their horses, and their popularity.

As the daughter of the Queen’s Master of the Revels Office, Adorna’s presence in such company was not only accepted but encouraged. Living at Richmond so close to the royal palace had many compensations, as her newly appointed father had only recently pointed out.

Adorna had already attracted smiles and admiring glances, her striking beauty and pale gold hair reflecting the similar pale gold of her new mare in the blue-patterned harness given to her last week for her twentieth birthday. By her side rode Master Peter Fowler, another member of the royal household, a young man on the upward current who privately believed that his future would be enhanced by his association with someone slightly above his station. Not that he was oblivious to Adorna’s physical attributes, but Peter was more ambitious than moonstruck, and his appearance by her side this morning was no coincidence.

In a sea of jewel colours, tossing plumes and a speckle of spaniels weaving between hooves, the company waited while the Queen and her Master Falconer cast their falcons up into the sky while down below the beaters flushed ducks from the river, putting them to flight. But, being on the edge of the gathering and not far from the river bank, Adorna’s flighty young mare took exception to wings whizzing overhead, squawking loudly. The mare bunched and staggered backwards, quivering with fright, and it was with some difficulty that Adorna controlled her and stopped her barging into nearby horses whose riders were looking skywards. Then, thinking that she was over that semi-crisis, she gave her attention to the falcons, which, in bringing down the ducks, dropped two of them into the river in a flurry of white feathers.

Everyone’s attention was now engaged in seeing who would be first to retrieve the flapping quarry for Her Majesty, none of them noticing how Adorna’s mare, still restive, had decided to join the retrieving party of her own free will against all her rider’s attempts to stop her. Moving backwards instead of forwards despite all that Adorna could do, the mare was beating a determined staccato with her hind hooves into the water around her. Men called, others laughed, including the Queen, some used their swords as fishing hooks, one lad plunged in bodily to earn the Queen’s favour, but no one—not even Peter—noticed how Adorna and her pale golden mare were now wallowing, hock deep, into the current.

She yelled to him, ‘Peter! Help me!’ but his attention was on the ducks like everyone else’s, and Adorna was obliged to use her whip to impel the horse forward as the water covered her feet, the hem of her long gown swirling wetly around one knee. But she had left it too late; the whip hit the water instead of the horse, which still refused to respond to her commands. Help came unexpectedly in the form of a large man and horse who plunged into the water ahead of her, grabbing unceremoniously at the mare’s bridle only seconds before the current swept over the saddle.

Concerned only with getting on to the bank as a team, she paid no attention to the man’s appearance except to note that his horse was very large and that he himself was powerful enough to drag the reins out of her hands and over the mare’s head and to haul the creature almost bodily through the muddy water on to dry firm ground.

Well away from the applauding crowd, Adorna found her voice. ‘Thank you, oh, thank you,’ she said, clutching at the pommel of the saddle as the mare lurched forward. ‘Thank heaven somebody noticed at last.’

Her thanks were misinterpreted. ‘If you think that’s the most effective way to be noticed, mistress, think again,’ the man snapped, devoid of any sympathy. ‘The applause you hear is for Her Majesty, not for your antics. Leave the retrieving to the hounds in future.’

It was not Adorna’s way to be speechless for long, but that piece of calculated rudeness was breathtaking. What was more, the man’s dismounting was far quicker than hers and, well before she could reply, she was being hoisted out of the saddle by two strong arms and set down upon the ground with the hem of her wet skirts and underclothes sticking nastily to her legs. His hands were painfully efficient.

‘I was referring, sir, to my predicament,’ she snapped back, shaking off his supporting hand. ‘If I’d planned on being noticed, as you appear to think, I’d not have chosen to back into the river before the Queen’s entire court, believe me. Nor was I in the race to retrieve a duck. Now, can I rid you of any more delusions before you go?’ Still not looking at him, she shook the full skirt of her pale blue gown, catching a glimpse of Peter out of the corner of her eye. He was dismounting. Kneeling. ‘Peter,’ she said, ‘get up off…oh!’ Her rescuer was doing the same.

The crowd had parted and, as Adorna sank into a deep wet curtsy, the Queen rode forward on a beautiful dapple grey. ‘Geldings make better mounts on these occasions, mistress, so I’m told,’ the Queen said. ‘Your mount is a beauty, but a little unmannerly perhaps?’ The embodiment of graciousness, the Queen exuded a sympathy for Adorna’s plight that came as a welcome change from the rescuer’s brusqueness.

Yet Adorna could not allow the chance to pass. She stayed in her curtsy, sending a haughty glance towards the man before making her reply. ‘Your Majesty is most kind. My mare is still young, though one would have to struggle to find a similarly good excuse for others’ unmannerliness.’ There was no mistaking the butt of her remark, the man in question glowering at her as if she were a troublesome sparrowhawk on his wrist, while the Queen and her Court’s laughter tinkled around them like splinters of breaking ice.

But Adorna’s glance had given her the information that she had already suspected, by his imperious manner and cultured voice—he was a self-opinionated wit-monger, albeit an extremely good-looking one, whose imposing stature was exactly the kind the Queen liked to have around her. Ill-featured people were anathema to her, especially men. He was dark-eyed and boldfaced with a square clean-shaven jaw, his head now bared to show thick dark waves brushed back off his forehead, a dent showing where his blue velvet bonnet had recently sat. His shoulders were broad enough to take her insult and, as the Queen signalled them to rise, Adorna saw that his legs were long and muscular, outlined in tight canions up to the top of his thighs to where his paned trunk-hose fitted. His deep blue velvet complemented her paler version perfectly, but that appeared to be their only point of compatibility.

The Queen was still amused. ‘There now, Sir Nicholas,’ she said. ‘Apparently it is not so much what one does as the manner in which one does it. I shall expect more from you when I have the misfortune to fall into the river.’

Sir Nicholas had the grace to laugh as he bowed to her. ‘Divine Majesty,’ he said, ‘I believe the Lady Moon will fall into the river before you do.’

‘I hope you’re right.’ She accepted the compliment and turned again to Adorna. ‘Mistress Pickering, there are few women who could look as well as you after such a fright. I hope you’ll not leave us.’

Adorna knew a command when she heard one. ‘I thank Your Majesty. I ask nothing more than to stay.’

‘Then stay close, mistress, and let my lord of Leicester’s man teach your pretty mare a thing or two about obedience. Sir Nicholas, tend the lady.’

Sir Nicholas bowed again as the Queen moved away to yet another scattering of applause at her graciousness, but Adorna had no intention of being tended by this uncivil creature, whatever the Queen’s wishes. She turned to Peter Fowler, but the voice at her back held her attention.

‘Mistress Pickering. Sir Thomas’s daughter. Well, well.’

Adorna spoke over her shoulder. ‘And you are one of the Master of Horse’s men, I take it, which would explain why you are more polite to horses than to their riders. What a good thing the same cannot be said of your master.’ It was well known that the handsome earl, Her Majesty’s Master of Horse, was desperately in love with the Queen.

‘My master, lady, has not yet had to drag Her Majesty out of the river in front of her courtiers. It’s not your pretty mare that needs a lesson in manners so much as its rider needing lessons in control.’ By this time the golden mare was eating something sweet from Sir Nicholas’s hand, as docile as a lamb. ‘Believe it or not, that is what Her Grace was telling you.’

Furiously, she rounded on him as Peter and two of her friends came to her aid, wringing the water from the hem of her gown. ‘Rubbish! There is no one in the world who speaks more candidly than the Queen. If that’s what she’d meant she’d have said so. Her Grace commands me to stay close and that is what I must do. I have thanked you for your assistance, Sir Nicholas, but now you are relieved of all further responsibility towards me, despite what Her Grace desires. Go and practise your courtesies on your horses.’

‘Mistress!’ Peter Fowler’s alarm warned her that her own courtesy was fraying around the edges. ‘This gentleman is Sir Nicholas Rayne, Deputy to Her Majesty’s Master of Horse.’

Before she could find another cutting retort, Sir Nicholas made a bow to Peter, smiling. ‘And you, Master Fowler, are the gentleman with the longest title in Her Majesty’s service. Gentleman Controller of All and Every Her Highness’s Works. Did I get it right?’ He was already laughing.

‘To the letter,’ said Peter. ‘In other words, Head of Security.’

But Adorna was not prepared for any signs of amity. She thanked her two friends and turned to Peter for assistance in remounting, though by now he was diverted by laughter and forestalled by Sir Nicholas who, in one stride, caught her round the waist and hoisted her into the saddle as if she were no more than a child.

For a brief moment, her view of the world turned sideways as her head came into contact with his neck and shoulder, her cheek feeling the softly curling pleats of the tiny white ruff that sat high above the blue doublet. She caught a whiff of musk from his skin and felt the firmness of his hands under her shoulders, and then the world was righted and she was looking down into his face, into two dark unsmiling eyes that held hers, boldly, for a fraction longer than was necessary. Confused by what she saw, she blinked, took the reins from him and waited as he and Peter unstuck the clinging fabric from her legs and arranged it in damp folds around her.

The Queen’s party had begun to move away.

‘Thank you, Sir Nicholas,’ she said, coldly, to the top of his blue velvet bonnet, watching the white and gold plumes lift and settle again. ‘I think you should go now.’

He made no reply to that. Instead, he took his own horse from a groom and vaulted into the saddle in one leap, reining the horse over expertly to walk on her other side, his nod to Peter cutting across her stony face.

By the time they reached the wide open fields well away from the river, Adorna’s composure was settling into an act which convinced those about her that she was comfortable. This was far from the truth, but showed the level of pretence of which she was capable. The wetness from her beautiful pale blue gown had now seeped up to her saddle, warm, sticky, and chafing her thighs: her golden mare’s hindquarters were caked with mud and the shining bells on her harness were clattering instead of tinkling. Far worse than any of that was the disturbing presence of the one who had saved her from a complete soaking, whose inscrutable expression gave her no inkling of his real reason for staying nearby, whether because he wanted to or because he had been commanded to. The pressure of his hands could still be felt, but she would not let him know, even by a sneaking exploration, that he had had the slightest effect.

As the Queen had commanded, Sir Nicholas drew her nearer to the centre of things than she had been before, which did even less for Adorna’s comfort. Having changed her peregrine falcon for a rare white gerfalcon, the Queen held it, hooded, on her wrist as a distant heron flew away upwards, ringing into the sky. The gerfalcon was released to pursue it, to climb even higher and then to stoop and dive, bringing the lovely thing down to the retrieving greyhounds whose speed prevented any injury to the precious raptor. Again, there was applause, then the announcement that they would have the picnic.

At this point, Adorna sidled invisibly back to her friends on the edge of the party, accepting whatever morsels of food were brought and passed around by the young pages. She made an effort to dismiss the incident of the river and to make herself affable to Peter, but her eyes had a will of their own, straying disobediently towards the tall well-built figure in deep blue braided with gold whose laughter was bold and teasingly directed towards a group of the Queen’s ladies.

Dressed entirely in white, the young Maids of Honour made a perfect foil for the Queen’s russet-and-gold that suited her so well. Like Adorna herself, she wore a high-crowned hat with a curl of feathers on the brim, a man’s-type doublet that buttoned up to the neck, and a full skirt. But whereas Adorna’s outfit was relatively modest in its decoration, the Queen had spared no effort to load herself with braids, chains and rings, frogging across her breast overlaid by pendants, and jewels winking from every surface, even from her neck-ruff of finest white lace.

Adorna’s gown had begun to dry by now and they would soon be away again on a search for herons and cranes, perhaps larks for those with smaller raptors. She went to where the mare was tied to a tree, her muzzle dripping with water from a bucket. ‘Your legs all right, my beauty?’ she whispered, taking a look at the mud-covered rear end. ‘We nearly came to grief, you and I, didn’t we, eh? Are you going to calm down this afternoon, then?’

‘That will depend,’ a voice said behind her, ‘on her rider more than anything else.’

Refusing to be drawn into another confrontation, Adorna clenched her teeth and slid one hand over the mare’s muddy rump, preparing to examine her legs. Sir Nicholas managed the gesture with far more confidence than she, overtaking her hand with his own as he came to stand before her, continuing the examination with all the assurance of a horseman. His hands were strong and brown with flecks of fine dark hair on the backs, his nails clean and workmanlike, and Adorna watched in reluctant admiration how his fingertips pressed and probed almost tenderly. She drew her eyes upwards to his face as he stood, and found that he was already regarding her in some amusement, knowing that the progress of his hands had been marked with an interest of a not altogether objective nature. Against her will, she found that her eyes were locked with his.

‘Well?’ he said, softly. ‘She’s still sound after her dunk in the river, and there’s nothing wrong with her temperament that a little gentle schooling won’t cure. Show her who’s master, though.’ As he spoke, his hands caressed the mare’s satin flanks, which twitched against the sensation, and Adorna knew that his words had as much to do with herself as they did with the mare. ‘She’s a classy creature,’ he said, ‘but not for amateurs.’ On his last phrase, his eyes left hers and rested directly on Peter Fowler who was just out of earshot, returning to her in time to see a flush of angry pink suffuse her cheeks.

If he wanted to believe that Peter was her lover, even though he was not, she was content for him to do so, for it would afford her some protection, his innuendo being impossible to misunderstand. She was as angry at her own uncontrollable shiver of excitement as at his blatant attempt to flirt with her after his earlier hostility, and the stinging rebuke came out like a rapier.

‘Don’t concern yourself with my mare’s requirements, sir,’ she said sharply. ‘Nor with mine. We have both managed well enough without your advice so far, so don’t think that your one act of bravado makes you indispensable to us. I think you should go back to your master and make yourself really useful. I bid you good day.’

She would have walked away on the last word, but his arm came across her, resting on the mare’s saddle, and she found herself imprisoned between him and the horse. ‘Ah, no, mistress,’ he said, without raising his voice. ‘That’s the third time you’ve ordered me to go, I believe. There are only a limited number of those who may give me orders, and you will never be one of them. What’s more, when the Queen commands me to tend a lady, I will tend her until she gives me leave to stop. If you dislike the idea so, then I suggest you make your objections known to her. Now, mistress, make ready to mount.’ And without the slightest warning other than that, he swooped and lifted her into his arms.

She should, of course, have been prepared for this, for he had already shown himself to be a man of immediate action. But strangely enough, she found that she was temporarily immobilised by his overpowering closeness, his refusal to be commanded, his boldness. Now his face was alarmingly close to hers and, instead of tossing her into the saddle as he had before, he was holding her deliberately tightly in his arms, preventing her from struggling.

‘You are a stranger, sir,’ she whispered, ‘and you are insulting me. My father will hear of this.’ Yet, as she spoke the words, she knew full well that her father would not hear of it from her lips and that, if this stranger was indeed insulting her, it was making her heart race in the most extraordinary manner that mixed fear with anticipation and a helplessness that made her feel guilty with pleasure. Or was it anger? Any other man, she thought, might have been expected to react with some concern at that threat, her father being Sir Thomas Pickering, Master of the Revels and therefore this man’s superior.

His expression showed no such disquiet. ‘No, mistress,’ he said. ‘I think not.’

She could feel his breath upon her face as he spoke, and she knew that he was allowing her to feel his nearness in the same way that an unbroken horse must be given time to get used to a man’s closeness, his restraint. His unsmiling mouth was firm and well proportioned and his nose, straight and smooth, led her examining eyes to his own that sparkled beneath high-angled brows, unflinching eyes of brown jasper, dark-lashed and suggesting to her an age of about thirty, by the experience written within them.

‘Let me go, I say. Please!’

As he moved to tip her upwards into the saddle, she saw a brief smile cross his face, which had disappeared by the time she looked again. He tapped her riding whip with one finger. ‘That’s for show, not for use,’ he said, severely. ‘Stallions need it, mares don’t.’

Adorna felt safe enough from that height to pretend unconcern. ‘Fillies?’ she said. ‘And geldings?’

The brief smile reappeared and vanished again as he recognised the return of her courage. ‘Remind me to tell you of the first some time. Of geldings I know little that would be of any use to you.’ And once again, she knew that neither of them was talking of horses.

The afternoon passed in a daze, though the only one to remark on her unusual quietness was Master Peter Fowler, who said, quite on the wrong tack, ‘Did that wetting upset you, mistress? It’s a pity you were not allowed to go home and change. You could have been back before Her Majesty noticed.’

That much was true, her home being a mere half-mile away over on the other side of the palace, a convenient place for Sir Thomas and Lady Marion to live when the Queen was at Richmond, and only one of several dotted about the home counties near the other royal residences. Life at court was a great temptation and Lady Marion, Adorna’s lovely mother, had no intention of leaving her handsome husband to the attentions of other women with whom he was obliged to come into contact. As Master of Revels, he probably saw more of them than the average household official, being responsible for the special costumes and theatrical effects needed for Her Majesty’s entertainment, an element of court life of great importance to balance the weightier matters of state.

Sir Thomas had expected to have Adorna’s assistance that day, but then had come Master Fowler’s request to take her to the Queen’s falconry picnic in the park, and he had not the heart to refuse. All the same, Master Fowler had better not harbour any fancy ideas involving Adorna: she could do far better for herself with her looks and connections.

Adorna’s looks were indeed something of which her parents were proud: pale blonde hair and startlingly beautiful features, large grey-blue eyes with sweeping lashes and a full mouth that, as far as her parents knew, had never been tasted by a man. Boys, perhaps, at Christmas, but never a man. Needless to say, there had been plenty of interest, so much so that Sir Thomas and Lady Marion had been criticised by family for being too lenient with her fastidiousness. At twenty years old, the elders said, it was time she was a wife and mother; let her put her high-faluting ideas aside and marry the richest of them, as other women did.

Fortunately for Adorna, her parents had so far ignored this advice, for they knew better than most how the Queen’s Court was a notorious hotbed of intrigue, liaisons, broken hearts and broken marriages, deceptions and dismissals. Adorna herself was not one of the Queen’s inner circle of courtiers nor had the Queen ever insisted on her regular appearance there, being sympathetic to the Pickerings’ views that lovely young women were often targets of men’s attractions for all the wrong reasons. Her Majesty had had enough problems in the past with her six young Maids of Honour, some of them losing their honour so quickly that it reflected badly on her, as their moral guardian.

Even so, Her Majesty was well aware of Adorna Pickering’s existence and, because she liked Sir Thomas and his wife, she encouraged their talented family to attend her functions. It worked both ways; while the Queen surrounded herself with beautiful and talented people, Adorna’s presence went some way towards advertising her father’s success as a new office-holder. Even though still part of the Great Wardrobe under Sir John Fortescue, his position carried with it a certain responsibility, one of which was to be seen in the best company.

To have access to Court without actually being sucked into the vortex of it was, Adorna believed, a very pleasant place to be, especially as her home was so conveniently near, with her father always at hand for protection if danger came a mite too close. On more than one occasion, he had been a very efficient tool to use against a too-persistent trespass, and running for cover became Adorna’s foolproof defence against over-attentive men, young or old, who would like to have taken more than was on offer. Though guests came and went constantly to her home at Sheen House next door to the palace, there were at least a dozen places in the fashionably meandering building where Adorna could remain out of touch until danger had passed.

True to form, she sought refuge with her father in the Revels Office for, despite Sir Nicholas’s refusal to be put off by the mention of him, she could think of no reason why the younger man would venture there to find her. There was still time left in the day to see how her father had proceeded without her, nor was it far for her and her maid to pass from Sheen House down what had lately become known as Paradise Road and through the gate in the wall of the palace garden.

To Sir Thomas’s annoyance, the Revels Office had no separate buildings of its own and was therefore obliged to share limited space with the Great Wardrobe where some of the Queen’s clothes were stored, others being in London itself. Consequently, tailors and furriers, embroiderers, carpenters and painters, shoemakers and artificers all worked side by side with never enough room to manoeuvre. Adorna’s creative talents were often put to good use in the Revels Office where men with flair and drawing ability were always in demand to design sets, special effects and costumes for the many Court entertainments.

Today, she had found a relatively private corner in which to examine some of the sumptuous and fantastic creations being prepared for a masque at the palace at the end of the week. She had helped to design the costumes and choose the materials and jewels, also to construct the elaborate head-dresses and wigs, for all the Court ladies taking part must have abundant blonde hair. She lifted one of the masks and held it above a flimsy gown of pale sea-green fringed with golden tassels, holding her head to one side to judge its effect.

‘Try it on,’ her father said. ‘That’s the best way to see.’

‘That won’t help me much, will it, Father?’

‘Perhaps not, but it’ll help me.’ He grinned and, to please him, she took up the mask and the robe stuck all over with silver and gold stars and went into a corner screened off from the rest of the busy room. Maybelle, her maid, went with her to help, though Adorna was wearing no farthingale or whalebone bodice to complicate matters. In a few moments she emerged to confront her father, but found to her surprise that he was not now alone but in the company of Sir John Fortescue and another officer of the revels who assisted her father.

This was not what Adorna had intended, for she was not wearing the correct undergarments, nor was the pale green robe with stars even finished, and it was only the papier mâché mask of a Water Maiden covering her face that hid her sudden blush of embarrassment as she held the edges of the fabric together across her bosom. And there was only one sleeve; her other arm was bare.

Before she could retreat, they had seen the half-dressed sea nymph and immediately began an assessment of its cost multiplied by eight, the amount of white-gold sarcenet with Venice gold fringe and the indented kirtles with plaits of silver lawn trailing from the waist. Not to mention the masks, head-dresses, shoes, stockings, tridents and other accessories, multiplied by eight.

‘Put the head-dress on, my dear,’ Sir Thomas said. ‘Which one is it? This one?’ He picked up a conch-shell creation covered in silver and draped with dagged green tissue to resemble seaweed and passed it to Maybelle.

‘Er…no, Father, if you please,’ Adorna protested.

But she was overruled by the three of them, and the thing was placed on her head, pushing down the mask in the process and making it difficult for her to see through the eyeholes. She must alter that before they were used. She heard murmurs of approval. ‘I must go,’ she mumbled into the claustrophobic space around her mouth. ‘Excuse me, if you please.’

Blindly, she turned and was caught by a hand on her arm before bumping into the person who had been standing silently at her back, someone whose familiar voice made her tear quickly at the mask, lifting it and tangling it with her loose hair and the head-dress in an effort to see where she was. The fabric across her front gaped as she let go of it and was snatched together again by Maybelle’s quick hand, but not before Adorna had seen the direction of the man’s eyes and the unconcealed interest in them.

‘Not a good day for water nymphs,’ Sir Nicholas whispered, letting go of her arm and stepping back to allow her to pass.

Summoning all her dignity, Adorna quickly snatched at a length of red tissue from the nearest tabletop and held it up to hide herself from the man’s gaze. ‘This is the Revels Office,’ she snapped, ‘not a sideshow.’

Amused, Sir Nicholas merely looked across at her father and Sir John.

Sir Thomas explained. ‘It’s all right, my dear. Sir Nicholas comes from the Master of Horse. He needs to know about our luggage for the progress to Kenilworth. Don’t send the poor man away before he’s fulfilled his mission, will you? Or I’ll have his lordship to answer to.’

Fuming, Adorna swept past him and returned to the screen, her face burning with annoyance that the man had once again seen her at a disadvantage. That he had seen her at all, damn him!

‘It’s all right, mistress,’ Maybelle whispered. ‘He didn’t see anything.’

‘Damn him!’ Adorna repeated, pushing her hair away. ‘Here, Belle. Tie my hair up into that net. There, that’s better.’ Her second emergence from the corner screen was, in a way, as theatrical as the first had been, for now she was not only reclothed in her simple day gown of russet linen but, covering the entire top of her body in an extravagant swathe of glittering red was the tissue she had snatched from the table. It trailed over one shoulder and on to the floor behind her, blending with the russet of her gown and contrasting brilliantly with the gold net caul into which her hair had hurriedly been bundled.

Astounded by the transformation as much as by the sheer impact of her beauty, the four men’s conversation dwindled to a stop as she approached, her head held high, and it was her father who spoke, at last. ‘Quick change, nymph!’ he laughed.

Sir Nicholas was more specific. ‘Water into fire,’ he murmured.

Sir John cleared his throat. ‘Ahem! Yes…well, your designs for the masque appear to be well in hand, Sir Thomas. I trust you’ll not leak any of this, Sir Nicholas. The masque theme must be kept secret until its performance.’ The Master of the Great Wardrobe looked at the younger man sternly from beneath handsome greying eyebrows.

‘I quite understand, sir. No word of the masque will be got from me, I assure you. My lord the Earl of Leicester is planning several for Her Majesty’s progress to Kenilworth, and he’s just as concerned about secrecy.’

‘Ah, yes,’ said Sir Thomas, ‘you need to know how many waggons and carts we need for the Wardrobe, don’t you? Well, why not come and join us for a late dinner on Wednesday? Lady Marion and I are celebrating my appointment with some friends. These two gentlemen will be there, too. Do you have a lady, Sir Nicholas?’

‘No, sir. Not yet.’ He smiled at their grins, and Adorna was aware that, had she not been there, more might have been said on that subject. But her father had blundered by inviting him to their home, which meant that both her places of refuge were now no longer safe from his intrusion.

Sir Thomas was clearly expecting his daughter’s approval of the invitation. He looked at her, eyebrows raised. ‘Adorna?’ he said.

The expression in her eyes, though fleeting, said it all. ‘No lady yet, Sir Nicholas? Perfect. Cousin Hester will be with us by tomorrow and Mother was wondering what to do about a partner for her. Now the problem is solved.’

Sir Nicholas bowed gracefully. ‘Thank you, mistress. I look forward to meeting Cousin Hester. Is she…?’

‘Yes, the late Sir William Pickering’s daughter. The heiress.’ That should turn your neat little head, she thought. ‘Now, if you will excuse me, gentlemen?’

Moving away from the group at the same time, Sir Nicholas was not inclined to let her go so easily, but strode alongside her, weaving his way in and out of the workers at the tables. By some miracle, he reached the door before her.

She glared at him. ‘I do not need lifting on to my horse, sir, I thank you. I left it at home.’

‘You’re walking? In this?’ He indicated the trail of billowing red stuff.

‘As long as you are gawping at me, yes. In this.’

‘And if I stop…er…gawping?’ He gave an impish smile.

She sighed, gustily, and glanced across at her father’s group. ‘Go back to your business, sir, if you please, and leave me to mine. You are in the wrong department.’

‘I’ll get used to it,’ he said softly, ‘and so will you, mistress.’

‘No, sir, I think not. See how you fare with Cousin Hester.’

‘And will Cousin Hester be in Water or in Fire?’

‘In mourning,’ she said, sweetly. ‘Good day to you, sir.’