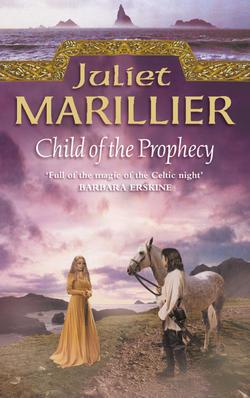

Читать книгу Child of the Prophecy - Juliet Marillier - Страница 7

Chapter Two

ОглавлениеThat day I set all my things in order. I tidied my narrow bed and folded the blanket. I swept the stone floor of my bedchamber, which was one of many caves in the Honeycomb’s maze of chambers and passages. I put away my shawl and outdoor boots in the small wooden chest which housed my few possessions. Our life was very simple. Work, rest, eat when we must. We needed little. Deep in the chest, half-hidden under winter bedding, was Riona. She was the only possession I had that was not a strict essential of life. Riona was a doll. When folk spoke of my mother, they would say how beautiful she was, and how slender, like a young birch, and how much my father had loved her. They’d say how she was always a little touched in the head, though it had shocked them when she did the terrible thing she did. But you never heard them talk about her talents, the way they’d mention that Dan was a champion on the pipes, or Molly the neatest basketweaver, or how Peg’s dumplings were the tastiest anywhere in Kerry. You’d have thought my mother had no qualities at all, save beauty and madness. But I knew different. You only had to look at Riona to know my mother had been expert with the needle. After all these years Riona was more than a little threadbare, her features somewhat blurred and her gown thin in patches. But she’d been made strong and neat, with such tiny, even stitches they were near invisible. She had fingers and toes, and embroidered eyelashes. She had long woollen hair coloured as yellow as tansy, and a gown of rose-hued silk over a lace petticoat. The necklace Riona wore, wound three times around her small neck for safekeeping, was the strongest thing of all. It was strangely woven of many different fibres, and so crafted that it could not be broken, not should the greatest force be exerted on it. Threaded on this cord was a little white stone with a hole in it. I did not play with Riona in Father’s presence. Of course, now I was too old for play. It was a waste of time, like taking silly, dangerous dives off the rocks when there was no need for it. But over the years Riona had shared countless adventures with Darragh and me. She had explored deep caves and precipitous gullies; had narrowly avoided falling from cliffs into the sea, and being left behind on the sand in the path of a rising tide. She had worn crowns of threaded daisies and cloaks of rabbit skin. She had sat under the standing stones watching us as if she were a queen surveying her subjects. Her dark embroidered eyes held a knowledge of me that could at times be disturbing. Riona did not judge, not exactly. She observed. She took stock.

That day I felt a strong need to be occupied, to channel my thoughts into the strictly practical. So, when my chamber was bare and clean, I went to the place where we kept our small supply of food, and took the fish the girl had brought, and a few turnips. The fish was already gutted and scaled. My father and I were not cooks. We ate because it was necessary, that was all. But I had time to fill. So I made up the fire, and let it die down, and then I roasted the turnips in the coals, and baked the fish on top. When it was ready I took a plateful down to the workroom for my father. But the door was bolted from the inside. I could not hear his voice chanting or speaking words of magic. The only sound was the harsh cawing of a bird within the vaulted chamber. That meant Fiacha was back. My heart sank, for I disliked Fiacha intensely. The raven came and went as he pleased, and when he stayed in the household he always seemed to be staring at me with his little, bright eyes, summing me up and finding me less than impressive. Then he’d be suddenly gone again, without so much as a by-your-leave. Perhaps he brought messages. Father never said. I did not like Fiacha’s sharp beak or the dangerous glint in his eye. He pecked me once when I was little, and it hurt a lot. Father said it was an accident, but I was never quite so sure.

I left the food outside the door. There was a rule which need not be spoken, that when the door was locked, one did not seek admittance. Some elements of the craft must be exercised in solitude, and my father sought always to deepen and extend his knowledge. It is too easy for an outsider to judge us wrongly, to see a threat in what we do, simply because of a lack of insight. Our kind are not always made welcome, not in all parts of Erin, for folk tell tales of us which are half truth and half a jumble of their own fears and superstitions. It was not by chance that my father had come to live in this distant, remote corner of Kerry. Here, the folk were simple souls whose lives turned on sea and season, whose world had no place for the luxury of gossip and prejudice. They had accepted him and my mother as just two more dwellers in the bay, quiet, courteous folk who left well alone. And everyone knew a settlement with its own sorcerer was the safest of places to live in. My father had quickly demonstrated that, for one summer, soon after his arrival in Kerry, the Norsemen came. All along the coast there were tales of their raids, the brutal killings, the rape, the burning, the stealing of women and children, and there were tales of the places where they’d come in their longships and simply moved in, taking the cottages and farms and settling down as if they’d a right to. But there was no Viking settlement in our cove. Ciarán had seen to that. Folk still told the story of how the longships with their carven prows had come into view, rowing in hard towards the shore with so little warning there was no time to flee for cover. The sunlight had flashed on the axes and the strange helms the men wore; the many oars had dipped and splashed, dipped and splashed as the fisherfolk stood frozen in terror, watching their death come closer. Then the sorcerer had walked out onto a high ledge of the Honeycomb with his staff of yew in his hand, and raised it aloft, and an instant later, great clouds had begun to roll in from the west, and the swell had risen till white-capped breakers began to pound the shore. The longships had begun to struggle and list, and the neat rows of oars were thrown into confusion. Within moments the sky was dark with storm, and the ocean boiled, and the folk watched round-eyed as the vessels of the Norsemen cracked and split and were torn asunder each in its turn. Later, children found strange and wondrous objects cast up on the shore. An armlet wrought with snakes and dogs, curiously patterned. A necklace in the shape of a tiny, lethal axe threaded on twisted wire. A bronze bowl. The shaft of an oar, fine-fashioned. The body of a man with pale skin and long, plaited hair the colour of wheat at Lugnasad. So, there was no Viking settlement in our cove. After that my father was revered and protected, a man who could do no wrong. When my mother died they grieved with him. All the same, they gave him a wide berth.

All that long day my father stayed in the workroom with the door bolted. When at last he emerged to take up the plateful of food and eat it abstractedly, not noticing it had gone cold waiting for him, he looked pale and tired. Sitting by the remnants of my small cooking fire, he picked at the congealing fish and had nothing to say. Fiacha had followed him and sat on a ledge above, staring at me. I scowled back.

‘Best go to bed, daughter,’ my father said, and coughed harshly. ‘I’m not good company tonight.’

‘Father, you’re sick.’ I stared with alarm as he struggled for breath. ‘You need help. A physic, at least.’

‘Nonsense.’ His expression was grim. ‘There’s nothing wrong with me. Go on now, off to bed with you. This will pass. It’s nothing.’

He had not convinced me in the slightest.

‘Father, please tell me what’s wrong.’

He gave a brief laugh. It was not a happy sound. ‘Where could one begin? Now, enough of this. I’m weary. Good night, Fainne.’

So I was dismissed, and I left him there, unmoving, staring into the heart of the dying fire. As I walked away to my chamber, the sound of his coughing followed me, echoing stark through the underground caverns.

She arrived one morning late in autumn, while Father was away fetching water. I made my way out, hearing her calling from the entrance. We had few visitors. But there she was; an old lady wrapped in shawls, trudging along on foot with never a bag or basket to her name. Her face was all wrinkled and her eyes so sunken you could scarce see what colour they were. She had a crown of dishevelled white hair and a very loud voice.

‘Well, come on, girl! Invite me in. Don’t tell me I wasn’t expected. What’s Ciarán playing at?’

She bustled past me and on down the tunnel towards the workroom as if the place belonged to her. I trotted after, hoping my father would not be too long. Suddenly she whirled back to face me, quicker than any old lady had the right to move, and now she was gazing intently into my eyes, as if assessing me.

‘Know who I am, do you?’

‘Yes, Grandmother,’ I said, for although she seemed quite different from the elegant woman I remembered, I could feel the magic seeping from every part of her, powerful, ancient, and it was plain to me who she must be.

‘Hmm. You’ve grown, Fainne.’ Clearly unimpressed, she turned her back on me and continued her confident progress through the darkened passages of the Honeycomb. Before the great door of the workroom, she halted. She put her hand out and gave a push. The door did not budge. Carven from solid oak, and set in a heavy frame which fitted tightly within its arch of stone, this entry was sealed by iron bolts and by words of power. My father guarded his knowledge closely. The old woman pushed again.

‘You can’t go in there,’ I said, alarmed. ‘My father doesn’t let anyone go in. Just him, and sometimes me. You’ll have to wait.’

‘Wait?’ She lifted her brows and gave an arch smile. On her ancient features, it looked hideous. Her eyes bored through me, as if she wished to read my thoughts. ‘Has your father taught you this trick, how to come out of a room and leave it locked from the inside?’

I nodded, scowling.

‘And how to unlock such a door?’

‘You needn’t think I’m going to open it for you,’ I told her, my voice growing sharp with anger at her temerity. I felt my face flush, and knew the little flames Darragh had once noticed would be starting to show on the edges of my hair. ‘If my father wants it locked, it stays locked. I won’t do it.’

‘Bet you can’t.’ She was taunting me.

‘I won’t open it. I told you.’

She laughed, a young girl’s laugh like a peal of little bells. ‘Then I’ll have to do it myself, won’t I?’ she said lightly, and raised a gnarled, knobby hand towards the heavy oak panels. She clicked her fingers just once, and a bright border of flame licked at the door, all round the edges. Smoke billowed, and I began to cough. For a moment I could see nothing. There was a popping sound, and a creak. The smoke cleared. The great door now stood ajar, its surface blackened and blistered, its heavy bolts hanging useless where they had fallen away from the charred wood.

I stood in the doorway, watching, as the old woman took three steps into my father’s secret room.

‘He won’t be happy,’ I said tightly.

‘He won’t know,’ she replied coolly. ‘Ciarán’s gone. You won’t see him again until we’re quite finished here, child; not until next summer nears its end. It’s just not possible for him to stay, not with me here. No place can hold the two of us. It’s better this way. You and I have a great deal of work to do, Fainne.’

I stood frozen, feeling the shock of what she had told me like a wound to the heart. How could Father do this? Where had he gone? How could he leave me alone with this dreadful old woman?

She was standing in front of the bronze mirror now, apparently admiring herself, for she took out a comb from a pocket in her voluminous attire and proceeded to drag it through her wild tangle of hair. Despite myself, I moved closer.

‘Didn’t Ciarán tell you about me, child? Didn’t he explain anything?’ She stared intently at her reflection. I came up behind, drawn to gaze over her shoulder into the polished surface.

The woman in the mirror stared back at me. She might have been sixteen years old, no more. Her hair was a glossier, prettier version of mine, curling around her shoulders with a life of its own, a rich, deep auburn. Her skin was milk-white, so pale you could see the faint blue tracery of veins on the pearly surface. Her figure was slender but shapely, with curves in all the right places. It was the figure I had tried to create for myself that day when I went down to the camp. I had thought myself skilful, but beside this, my own efforts were paltry. This woman was a master of the craft. I looked into her eyes. They were deep, dark, the colour of ripe mulberries. They were my father’s eyes. They were my own eyes. The old woman smiled back from the mirror, with her red, curving lips and her small, sharp white teeth.

‘As you see,’ she said with a mirthless chuckle, ‘I’ve a lot to teach you. And we’d best start straight away. Making you into a fine lady is going to be quite a challenge.’

For as long as I could remember, it had been the two of us, my father and I, working together or working separately, the day devoted to the practice of the craft. Our meals, our rest, our contacts with the outside world were kept to what was strictly essential: the fetching of water, the gathering of driftwood for the fire. Fish accepted from the girl at the door. Messages entrusted to Dan Walker. I had had the summers with Darragh. But Darragh was gone, and I was grown up now. Those times were over. My father and I understood each other without much need for words. Sometimes he would explain a technique or the theory behind it. Sometimes I would ask a question. Mostly, he let me find out for myself, with a little guidance here and there. He let me make my own mistakes and learn from them. That way, he said, I would become more responsible, and retain those things I most needed to know. Indeed, in time this discipline would lead not just to knowledge, but to understanding. It was an orderly, well-structured existence, if somewhat outside the patterns of ordinary folk.

My grandmother had quite a different method of teaching. She began by telling me Ciarán had neglected my education sorely; the least he could have taught me was to eat politely, not shovel things with my fingers like a tinker’s child. When I sought to defend my father, she silenced me with a nasty little spell that made my tongue swell up and grow fuzzy as a ripe catkin. No wonder she had said she could not live in the same place as her son. One of our most basic rules was that the craft must never be used by teacher against student, or student against teacher. My father would have recoiled from the idea of using magic to inflict punishment. Grandmother employed it with no qualms whatever. I hated the way she spoke of him, of her own son.

‘Well,’ she observed as she watched me eating my fish, her eyes following each scrap as it travelled from platter to lips, ‘he’s taught you shape-shifting and manipulation and sleight of hand. How much good will those skills be to you when you sit at table with the fine folk of Sevenwaters? Can you dance? Can you sing? Can you smile at a man and make his blood stir and his heart race? I thought not. Don’t gape, child. Your education’s been quite inadequate. I blame those druids, they got hold of your father and filled his head with nonsense. It’s just as well he called me when he did. Before I’m done with you, you’ll be expert at the art of twisting a man around your little finger – clumsy, plain thing that you are. I’m an artist.’

‘I have learned much from my father,’ I said angrily. ‘He is a great sorcerer, and deeply respected. I’m not sure we need your – artistry. I have both lore and skills, and will improve both as well as I can, for my father has given me a love of learning. Why spend time and energy on table manners?’

She laughed her young woman’s laugh, so incongruous as it pealed from that wizened, gap-toothed mouth.

‘Oh dear, oh dear. It stamps its little foot, and the sparks fly. The first thing you need to learn is not to give yourself away like that, child. But there’s more, so much more. I know your father has given you a grounding in the skills. The bare bones, so to speak. But you can achieve great things at Sevenwaters if you make the most of your opportunities. I’ll help you, child. Believe me, I know these people.’

From that point on she took charge. I was used to lessons and practice. I was used to working long hours, and being perpetually tired, and keeping on regardless. But these lessons were so tedious. How to eat as neatly as a wren, in tiny little morsels. How to giggle and whisper secrets. How to hold myself upright as I walked, and sway my hips from side to side. This one was not easy, with my foot the way it was. In the end she grew exasperated.

‘You’ll never walk straight in your own guise,’ she told me bluntly. ‘You’ll never dance without making a fool of yourself. No matter. You can use the Glamour when you will. Make yourself as graceful as you want. Have the loveliest feet in the world, if there’s need of them. The only problem is, it gets tiring. Keeping it up all the time, I mean. It wears you down. Why do you think I’m a wrinkled old hag? Our kind live long. Too long, I sometimes think. But I’m the way I am from being charming for Lord Colum all that time, keeping him dancing to my will.’ She gave a sigh. ‘Ah, now, there was a man. Shame that little upstart Sorcha thwarted me. If she hadn’t done what she did, there’d have been no need for all this. It would all have been mine, and in his turn, Ciarán’s. Your wretched mother would never have existed, and nor would you, pet. Think what I could have achieved. It would all have been ours, as it should have been. But she did it, she outwitted me, she and those – those creatures that call themselves fancy names. Otherworld beings. Huh! Power went to their heads a long time ago, that’s their problem. Shut our kind out. We were never good enough for them, and don’t they love reminding us of it? Well, we’ll see what the Fair Folk make of my little gift to them. They’ll be laughing on the other sides of their faces when your work is done, girl.’

I hesitated to ask her what she meant. She was quick to ridicule and to punish when she thought me slow or stupid.

It was too late, Grandmother said, for me to learn to play the harp or flute. I refused to sing, even when she punished me by taking away my voice. I did well enough without it, being used to long days of silence, and in time she abandoned her efforts to extract any form of music from me. She discovered very quickly that my skills in reading and writing far surpassed her own. My sewing was another matter; she pronounced it rudimentary in the extreme. Materials were found in a flash, fine silks, gossamer fabrics, plain linen to practise on first. By lantern light I stabbed my fingers and squinted my eyes and cursed her silently. I learned to sew. She watched me a little quizzically, and once she said, ‘This brings back some memories. Oh, yes.’

There were other lessons she taught me, lessons I would blush to relate. It was necessary, my grandmother said, for I was a girl, and to get anywhere in the world I must be able to attract a man and to hold him. It was not just a case of learning a certain way of walking, and a particular manner of glancing, or even of knowing the right things to say and when to remain silent. Nor was it simply a matter of using the Glamour to make oneself more beautiful or more enticing, though that certainly helped. Grandmother’s teaching was a great deal more specific. It made me cringe to hear her sometimes. It made me hot with embarrassment to be required to demonstrate before her what I had learned. The thought of actually doing any of it made me recoil in horror. She thought me very foolish, and said so. She reminded me that I was in my fifteenth year and of marriageable age, and that I had better make the best of what little I had in the way of natural charms, and learn how to use the craft to enhance them as required, or I’d have no hope of making anything of myself. It was plain to me, as I struggled with these lessons, why my father had summoned her to guide me. If it was true that I needed to acquire these skills, to know these intimate secrets, then it was equally clear he could not have taught me them himself. There are some things a girl cannot discuss with her father, no matter how close to him she may be. But I lay awake at night, wondering at his decision, for Grandmother was a cruel teacher, and her presence in the Honeycomb cast a cold shadow on my days and filled my nights with evil dreams. Why had he gone away, so far I did not even know where he was? Was that in itself some kind of test? He had never left me before, not even for a single night. I was heartsick and lonely, and I was worried about him. He was my world, my family, my only constant. I needed him; he surely needed me, for there was no other on whom he bestowed that rare smile which lit up his sombre features and showed me the man for whom my mother had left the world behind. Was he afraid of Grandmother? Was that why he had left me to her mercies? My dreams showed him gaunt and white, coughing painfully somewhere in a dark cave all by himself. I wished he would come home.

Autumn advanced into winter, and the lessons went on at a relentless pace.

‘Very well, Fainne,’ Grandmother said one day, quite abruptly, as we sat in the workroom resting. All afternoon she had made me turn a spider into other forms: a jewel-bright lizard; a tiny bird with fluttering wings that blundered, confused, into the stone walls; a mouse that came close to making its escape through a crack until I clicked my fingers to change it into a very small fire-dragon, which puffed out a very small cloud of vapour, flapping its leathery wings in miniature defiance. I was exhausted, as limp in my chair as the spider which now hung, still as if dead, in its web high above me. ‘Time for a history lesson. Listen well, and don’t interrupt if there’s no need of it.’

‘Yes, Grandmother.’ Obedience was the easiest course to take with her. She was ingenious in her methods of punishment, and she disliked to be challenged. I far preferred Father’s methods of teaching which, though strict, were not unkind.

‘Answer my questions. Who were the first folk in the land of Erin?’

‘The Old Ones.’ This type of inquisition was easy. Father had imparted the lore over long years, and he and I were fluent in question and answer. ‘The Fomhóire. People of the deep ocean, the wells and the lake beds. Folk of the sea and of the dark recesses of the earth.’

Grandmother gave a peremptory nod. ‘And who came after?’

‘The Fir Bolg. The bag men.’

‘And after them?’

‘Then came the Túatha Dé Danann, out of the west, who in time sent the others into exile and spread themselves all across the land of Erin. Long years they ruled, until the coming of the sons of Mil.’

‘Very well. But what do you know of the origins of our own kind?’ Her eyes were sharp.

‘Our kind are not in the lore. I know that we are different. We are cursed, and so we are ever outside. We are not of the Túatha Dé. Neither are we mortal men and women. We are neither one thing nor the other.’

‘That much you’ve got right. We’re outside because we were put there. One of us transgressed, long ago, and they never let us forget it. Know that story, do you?’

I shook my head.

‘We’re their descendants, whether they like it or not. Fair Folk, or whatever they choose to call themselves. Gods and goddesses every one, superior in every way, drifting around as if they owned the place, as they did, of course, after packing the others off back into their nooks and crannies. But someone dabbled in what she shouldn’t, and that started it all off.’

‘Dabbled? In what?’

‘I said, don’t interrupt.’ She glared at me, and I felt a sharp, piercing pain in my temple. ‘Back in those first days we could do it all, had every branch of the craft at our fingertips. Shape-shifting, transformation. Healing. Mastery of wind and rain, wave and tide. We were gods indeed, and no wonder the Old Ones crept back to their caves with their tails between their legs. But there are some byways of the craft that should not be tampered with, not even by a master. Everyone knew that. It’s perilous to touch the dark side; best leave it alone, best stay well away. Unfortunately there was one who let curiosity get the better of her. She played with a forbidden spell; called up what should have been left sleeping. From that day on there was an evil let loose that was never going to go away. So she was cast out, and part of her penalty was to be stripped of the ability to use the higher elements of magic: the powers of light, the healing, the flight. All she had left was the dross, sorcerer’s tricks: she could meddle, and she could perform transformations, a frog into a man maybe, or a girl into a cockroach. She had the Glamour. Precious little, compared with what she’d lost. She attached herself to a mortal man, since none of the high-minded ones’d have her, not after what she’d done. And you know what that means.’

This time an answer seemed to be expected. ‘That she herself would become mortal?’

‘Not exactly. Our kind live long, Fainne; far beyond the human span. But it did mean she in her turn would die. She would survive to see her family perish of old age before she herself moved on. Her descendants bore the blood of the cursed one, through the ages. Every one of us has her eyes. Your eyes, girl. Every one has the craft, but narrowly, you understand. Some things will always be beyond us. That rankles. That hurts. It should be ours. The punishment was unjust; too severe.’

I opened my mouth, thought better of what I was about to say, and shut it again.

‘Thinking of your father, are you?’ she said, unsmiling. ‘Thinking he seems to manifest a somewhat wider range of talents than those I described? You’re right, of course. I chose his father well: no less than Colum, Lord of Sevenwaters. They’re druid folk, that family. Look how they live, shut away in their precious forest, surrounded by those Others. They’ve got the blood of the Old Ones, mixed with the human strain. Ciarán’s different. Special. He should have ruled there after Colum. Isn’t he the seventh son of a seventh son? But I was foiled. Foiled by that wretched girl and her cursed brothers. They’re the ones you need to watch out for. The ones with the Fomhóire streak in them.’

I frowned in concentration. ‘Why would that be dangerous, Grandmother? The Fomhóire were not users of high magic.’

‘Ah. There’s high magic, and there’s sorcerer’s magic, and there’s another kind. You might call it deep magic. That’s what the folk from Sevenwaters have, and we don’t, child. Not all of them, mind. Most of them are simple fools like your mother, weak-willed and weak-minded. How my son ever fell for that empty little featherhead, I cannot understand. Niamh ruined his life; she weakened him terribly. But now there’s you, Fainne. You’re my hope.’

I had learned that snapping back was pointless, though her dismissal of my mother wounded me. ‘Deep magic?’ I queried. ‘What is that?’

‘The magic of the earth and the ocean. That’s where those folk came from, long ago. That’s why they cling to the Islands. They are no sorcerers. They don’t work spells. But some of them have the ability to speak to one another in the mind, without words. You don’t know how hard I tried to develop that. Wore myself out. Either you have it or you don’t. One or two of them can read the future. Powerful tools, both of them. And some of them have healing skills far beyond a physician’s.’

‘Is that all?’

‘All, she says!’ Her laugh mocked me. ‘Isn’t that enough? Those gifts shut me out of achieving my goal for nigh on two generations, girl. They took my son from me and turned him soft. But now it’s different. I have you, Fainne, and I have a new goal, a far grander one. You’ve got a little bit of everything in you, thanks to your mother. That was the one good thing she did for you, pathetic wretch that she was. I’ve never understood it. If Ciarán had to throw himself away on one of the Sevenwaters brats, why not choose the other sister? A child of that liaison would have had rare skills indeed. Never mind, Fainne. You bear the blood of four races. That has to count for something.’

This time I found it impossible not to challenge her. ‘I don’t like you to speak of my mother that way,’ I said, glaring.

‘No? I speak only the truth, child. Besides, what would you care? You scarcely remember her, surely. But I suppose all your attitudes come from your father. He’ll hear no ill spoken of his beloved Niamh. To him she was a princess, a creature of perfection who couldn’t set a foot wrong. He let losing her eat him up. Now, Fainne.’ Her tone had changed abruptly. ‘You’ve done quite well so far, child; we should be ready in time if you keep your mind on learning. Tomorrow I’ll outline what is expected of you at Sevenwaters. All this, you understand, the airs and graces, the easy conversation, the skills of the bedchamber, all this is only a tool, part of the means to an end. Tomorrow I’ll begin to explain what that end is. You’ve quite a task ahead of you, granddaughter. Quite a task. Now, off to bed with you, you’ll need all the rest you can get.’

That night, alone in my chamber with a candle for company and the ocean roaring outside, I opened the wooden chest and brought out Riona. She seemed a little crumpled from being squashed under blankets, and I thought I detected a trace of a frown on her neatly stitched features. I untangled her yellow hair and refastened the ties at the back of her gown. Tonight, suddenly I did not feel so grown up any more, and as I blew out the candle and lay down on my bed I kept Riona by me, something I had not done for a long time.

‘Is it true?’ I whispered into the darkness. ‘Is that all my mother was, a stupid girl who blighted my father’s life? Is that why he doesn’t want to talk about her? But he said he loved her. If he would talk about her, then maybe I would remember her. Maybe I would remember something. Some little thing.’

Riona did not reply. Her presence by me was comforting, nonetheless. My fingers touched the strange woven necklace she wore, stroked the cool smooth surface of the white stone threaded on it.

‘Perhaps it’s best,’ I said, to her or to myself. ‘Perhaps it’s best that I don’t know. She was one of them, the human kind, the family of Sevenwaters. I am of the other kind; I am my father’s daughter. Best if I never know.’ But my hand brushed the soft silk of Riona’s skirt, and as I fell asleep I was seeing my mother’s fingers, the swift flash of the needle as she sewed the little gown with tiny, even stitches. A gift for her daughter, to remember her by; a small friend to comfort me in the darkness when she was gone.

The next morning Grandmother set things out for me.

‘Now, Fainne,’ she said, watching me very closely as I stood before her in my plain gown and serviceable shoes, my hands clasped behind my back. ‘Why do you think your father wants you to go to Sevenwaters? Is not that the one place he longs to obliterate from his memory, yet cannot? Why would he send you there, his only daughter, into the heart of his enemy’s territory?’

‘I am the granddaughter of a chieftain of Ulster,’ I told her. ‘Father said the folk of Sevenwaters have a debt to repay. He thinks I must learn to move in that circle, since there is no real future for me here in Kerry.’ A shiver went through me. It occurred to me for the first time that I might never return to the Honeycomb. The thought terrified me. ‘I trust my father,’ I went on as steadily as I could. ‘If he wishes me to travel to Ulster, then that must be the right thing.’

Grandmother grimaced, awakening a network of deep wrinkles in her ancient skin. ‘Your confidence in Ciarán’s judgement is touching, my dear, if ill-founded. His decision is sound enough, it’s his reasons that leave something to be desired. I put that down to his druid training. That wretch, Conor, has a lot to answer for. He and those brothers of his robbed my son of his birthright, and muddled his head with foolish ideas, so he doesn’t know what’s what any more. They should never have survived what I did to them. But that’s beside the point. Your father only told you half the truth, Fainne. Ciarán’s sick. Very sick. He’s sending you away because he sees a day, quite soon, when he’ll no longer be here to provide for you.’

I felt the blood drain from my face. ‘What?’ I whispered foolishly.

‘Don’t believe me? You should. I’m in the very best position to know this. Ciarán won’t leave his precious little apprentice here with the fisherfolk, to become another wife with a gaggle of squalling brats at heel. He can’t leave you with me; I come and go as I please. So he’s left with only one option. Your uncle, Lord Sean of Sevenwaters; Conor, the arch druid; the elusive Liadan; those are the only family you’ve got. Your father sees no alternative.’

‘You mean – you mean this cough, this pallor, you mean he is – dying?’ I forced the word out. ‘But – but how can this be? Our kind are not like ordinary men and women, we live long – how can he be so sick? He said he was well. He said there was nothing wrong –’

‘Of course he said that. But there are some maladies beyond mortal remedy, Fainne; some sicknesses that can strike even the most powerful mage. He didn’t tell you the truth because he knew you wouldn’t agree to go, if you knew.’

‘He was right,’ I said, gritting my teeth. ‘I won’t go. I cannot leave him. How could he not tell me?’ The two of us had been so close, had shared such long times of perfect understanding, of wordless cooperation. Hurt lodged deep within me like a cold stone.

Grandmother was calm. ‘Let me explain something to you,’ she said. ‘It’s not the human folk of Sevenwaters that matter, child. It’s the power behind them: those Otherworld creatures with their fancy manners, and their grip on the rest of us. You will go to Sevenwaters, if not for your father, then for me. I’ve a task for you to undertake, a mission for you to complete. This is big, Fainne. Far bigger than you imagine.’

‘But Father said –’

‘Forget that. I’m his mother. I know what I’m talking about. There’s one reason for you to go to Sevenwaters, and one reason alone. My reason. Why do you think I came here, Fainne? I’ve been watching you, these long years; waiting until you were ready for this. You will complete what I started. You will achieve the success long denied our kind. You’ll show the Fair Folk that the outcast can be strong, strong enough to deny them their heart’s desire. You will thwart their long scheme. They will fall together, the folk of Sevenwaters and their Otherworld shadows. That’s your task.’

I gaped at her. ‘But – but, Grandmother, the Túatha Dé Danann? Who could challenge such power? I would be crushed.’

She grinned sourly. ‘I did it, and I’m still here. A little battered, but I have my will. And I nearly succeeded. They’re much weakened since the Islands were lost to the Britons. They had a plan for that girl, Sorcha, and her muddy-boots of a lover. They have a plan for Sevenwaters. I nearly ruined the first. But the girl was too strong for me. I forgot the Fomhóire streak. Never do that, Fainne. Watch out for it. Now you’ll thwart the second plan. The Fair Folk want the Islands back. They want it all played out in accordance with the prophecy. Down to the last word. And it’s all set to happen when another year has run its course. So I’ve heard.’

‘Prophecy?’ My head was spinning, quite unable to come to terms with the horror, the grandeur and the folly implicit in her words.

‘Didn’t Ciarán tell you anything? The Islands were taken by the Britons generations back. Ever since then, Sevenwaters has warred with Northwoods. Until the Islands come back to the Irish, both Fair Folk and human folk remain in disarray. They need them. The high and mighty ones want the Islands guarded. Watched over. That’s the only way they can protect themselves from what’s to come. The prophecy said it would take a child who was neither of Britain nor of Erin, but at the same time both. And there’s some nonsense about the mark of the raven. Well, they’ve got him at last, the leader long hoped for, grandson of that wretched Sorcha. He’s grown up, and ready to do battle with Northwoods, and he’s got a formidable force lined up behind him. It won’t be long now. Not next summer but the one after, that’s what’s being said. Your task is to stop them. Simple, really. You must make sure they don’t fight, or if they do, make sure they lose. Just think of that. We, the outcast ones, at last gaining the upper hand over the Fair Folk. I’d like to see the expressions on their faces then.’

I was so astonished I could barely speak. ‘But how could I achieve such a thing? And why has Father never spoken of this? It would be impossible, for one girl to stop an army. I would not attempt such a task. It’s ridiculous.’

‘Who are you calling ridiculous?’ The old woman fixed me with her berry-dark eyes.

I felt my backbone turn to jelly, but I tried to hold firm. ‘I would not attempt such a thing without Father’s approval,’ I said. ‘It is impossible to believe he would support such an idea.’

Grandmother’s gaze sharpened. Her expression alarmed me. I felt a prickle of fear go up and down my neck.

‘Ah,’ she said, in a very soft voice that clutched at me like a chill hand. ‘You’ll go, Fainne. And you’ll do exactly as I bid you do, from now on. I will not see my plans thwarted a second time.’

‘I won’t,’ I said, trembling. ‘I won’t leave my father. I don’t care how strong your magic is. You can’t make me do it.’

Grandmother laughed. This time it was not the tinkling bell-like laugh, but a harsh chuckle of triumphant amusement. ‘Oh, Fainne. You’re so young. Wait until you begin to feel the power within yourself, wait until men commit murder for you, and betray their strongest loyalties, and turn against what is dearest to their spirits. There’s no pleasure like that. Wait until you recognise what you have within you. For you may be Ciarán’s daughter, and carry the influence of his druid ways and his excess of conscience, but you are my granddaughter. Never forget that. You will always bear a little part of me somewhere deep within you. There’s no denying it.’

‘You cannot make me do bad things. You cannot force me to act against my father’s will. I must at least ask him.’

‘You’ll find I can do just that, girl. Exactly that. From this moment on, you will perform whatever tasks I set you. You will pursue my quest to the bitter end, and achieve the triumph that was denied me. You think, perhaps, that if you disobey me, you will be made to suffer. A slight headache here; a bout of purging there. Warts maybe, or a nasty little boil in an awkward spot. I’m not so simple, Fainne. Act against my orders, and it is not you who will be punished. It is your father.’

My heart thumped in horror. ‘You can’t!’ I whispered. ‘You wouldn’t! Your own son? I don’t believe you.’ But that was not true; I had seen the look in her eyes.

She grinned, revealing her little pointed teeth, a predator’s teeth. ‘My own son, yes, and what a disappointment he turned out to be. As for my will, you’ve already had a demonstration of that. Your father’s malady is not some ague he picked up, or the result of nerves and exhaustion. It’s entirely of my doing. I have been planning for some years, and watching the two of you. He senses it, maybe; but I caught him unawares, and now he cannot shake me off. So he sends you away to what he deems a place of safety. Straight off to Conor, his arch enemy. Ironic, isn’t it?’

‘You’re lying!’ I retorted, torn between horror and fury. ‘Father’s too quick with counter-spells, he’d never let it happen. There’s no sorcerer in the world stronger than he is.’ My voice spoke defiance while my heart shrank with dread; she had us trapped, the two of us, trapped by the love we bore each other. It was she who was strongest; she had been all along.

‘Weren’t you listening?’ she asked me. ‘Ciarán could have been what you say. He could have been the most powerful of all. But he threw it away. He let hope destroy him. He may still practise the craft, but he hasn’t the will now. He was easy prey for me. You’ll need to be extremely careful. I’ll give you some instructions before you leave. The slightest deviation from my orders, and your father goes a little further downhill. You’ve seen how he is. It wouldn’t take many mistakes on your part to make him very sick indeed; almost beyond saving. On the other hand, do well, and he may just get better. See what power I’m giving you.’

‘You won’t know.’ My voice was shaking. I’ll be at Sevenwaters, and you said yourself you cannot read minds. I could disobey and you would be none the wiser.’

Her brows rose disdainfully. ‘You surprise me, Fainne. Have you not mastered the use of scrying bowls, the art of mirrors? I will know.’

I wrapped my arms around myself, for there was a chill in me that would remain, now, on the brightest of summer days. My father sick, suffering, dying; how could I bear it? This was cruel indeed, cruel and clever. ‘I – I suppose I have no choice,’ I muttered.

Grandmother nodded. ‘Very wise. It won’t be long before you’re enjoying it, believe me. There’s an inordinate amount of pleasure that can be had in watching a great work of destruction unfold. You’ll have a measure of control. After all, you do need to be adaptable. I’ll give you some ideas. The rest you can work out for yourself. It’s amazing what power a woman can enjoy, if she learns how to make herself irresistible. I’ll show you how to identify which man in a crowd of fifty is the one to target; the one with power and influence. I did that once, and I nearly had everything I wanted. I came so close. Then that girl ruined everything. I’ll be as glad as Ciarán will be to see her family fail, finally and utterly. To see them disintegrate and destroy themselves.’

She fumbled in a concealed pocket.

‘Now. You’ll need every bit of help you can get. This will be useful. It’s very old. A little amulet. Bit of nonsense, really. It’ll protect you from the wrong sorts of influence.’ She slipped a cord over my neck. The token threaded on it seemed a harmless trinket; a little triangle of finely wrought bronze whose patterns were so small I could hardly discern the shapes. Yet the moment it settled there against my heart, I seemed to see everything more clearly; my anxiety faded, and I began to understand that perhaps I could do what my grandmother wanted after all. The craft was strong in me, I knew that. Maybe all I needed to do was follow her orders and all would be well. I closed my fingers around the amulet; it had a sweet warmth that seemed to flow into me, comforting, reassuring.

‘Now, Fainne,’ Grandmother said almost kindly, ‘you must keep this little token hidden under your dress. Wear it always. Never take it off, understand? It will protect you from those who seek to thwart this plan. Ciarán would say the powers of the mind are enough. Comes of the druid discipline. But what do they know? I have lived amongst these folk, and I can tell you, you’ll need every bit of assistance you can get.’

What she said sounded entirely practical. ‘Yes, Grandmother,’ I said, fingering the bronze amulet.

‘It will strengthen your resolve,’ Grandmother said. ‘Keep you from running away as soon as things get too hard.’

‘Yes, Grandmother.’

‘Now tell me. Is there anyone you’ve taken a dislike to, in your sheltered little corner here? Got any grudges?’

I had to think about this quite hard. My circle was somewhat limited, especially of late. But one image did come into my mind: that girl with her sun-browned skin and white-toothed smile, wrapping her shawl around Darragh’s shoulders.

‘There’s a girl,’ I said cautiously, thinking I had a fair idea of what was coming. ‘A fishergirl, down at the cove. I’ve no great fondness for her.’

‘Very well.’ Grandmother was looking straight into my eyes, very intently. ‘You know how to turn a frog into a bird, and a beetle into a crab. What would you do with this girl?’

‘I –’

‘Scruples, Fainne?’ Her tone sharpened.

‘No, Grandmother.’ I had no doubt she had told me the truth, and I must do as she asked. If I failed, my father would pay. Still, a transformation need not be for ever. It need not be for long at all. I could obey her, and still do this my own way.

‘Good. Just as well the weather’s better, isn’t it? You can walk down this afternoon and stretch your legs. Take that dour excuse for a raven on an outing, it still seems to be hanging about. You can do it then. You’ll need to catch her alone.’

‘Yes, Grandmother.’

‘Focus, now. Remember all you’re doing is making a slight adjustment. Quite harmless, in the scheme of things.’

I timed it so the boats were still out and the women indoors. If I were seen at all, two and two would most certainly be put together. I lacked the skill to command invisibility, for, as my grandmother had told me, we had been stripped of the higher powers. Still, I was able to slip from rocky outcrop to wind-whipped bushes to stone wall without drawing attention to myself, crooked foot or no, and it appeared that Fiacha knew quite well what I was doing, for he behaved exactly like any other raven that just happened to be in the settlement that day. Most of the time he sat in a tree watching me.

The girl was outside her cottage, washing clothes in a tub. Her glossy brown hair was dragged back off her face, and she seemed more ordinary than I had remembered. Two very small children played on the grass nearby. I watched for a little, unseen where I stood in the shade of an outhouse. But I did not watch for long; I did not allow too much time for thought. The girl looked up and said something to the children, and one of them shrieked with laughter, and the girl grinned, showing her white teeth. I moved my hand, and made the spell in my head, and an instant later a fine fat codfish was flapping and gasping on the earthen pathway, and the brown-skinned girl was gone. The two infants appeared not to notice, absorbed in their small game. I watched as the fish twisted and jerked, desperate for life. I would leave it just long enough to show I was strong; just long enough to prove to my grandmother that I could do this. Then I would point my finger and speak the charm of undoing. Now, maybe. I began to focus my mind again, and summon the words. But before I could whisper them, a woman came bustling out of the cottage, a sharp knife in her hand and a frown on her lined features. She was a big woman, and she stopped on the path right before me, blocking my view of the thrashing fish. And while I could not see the creature I had changed, I could not work the counter-spell.

Move, I willed her. Move now, quick.

‘Brid!’ she called. ‘Where are you, girl?’

Move away. Oh, please.

‘Where’s your sister gone?’ The woman seemed to be addressing the two infants, not expecting a reply. ‘And what’s this doing here?’ Before my horrified gaze she bent and scooped up something from the path. If only she would turn a little, all I needed was a glimpse of silvery tail or staring eye or gasping mouth, and I could change the girl back. I would do it, even if it meant all knew the truth. If I did not do it, I would be a murderer.

‘Who’s been here?’ the woman asked the children. ‘Tinker lads playing tricks? I’ll have something to say to your sister when she gets back, make no doubt of that. Leaving the two of you alone with a tub of wash water, that’s asking for trouble. Still, this’ll go down well with a bit of cabbage and a dumpling or two.’ She made a quick movement with her hand, the one that held the knife, and then, only then, she half-turned, and I saw the fish hanging limp in her grip, indeed transformed into no more than a welcome treat for a hungry family’s table. I was powerless. It was too late. The greatest sorcerer in the world cannot bestow the gift of life. A freezing terror ran through me. It was not just that I had done the unforgivable. It was something far worse. Had not I just proved my grandmother right? I bore the blood of a cursed line, a line of sorcerers and outcasts. It seemed I could not fight that; it would manifest itself as it chose. Were not my steps set inevitably towards darkness? I turned and fled in silence, and the woman never saw me.

Later we heard news from the settlement of the girl’s disappearance. A search was mounted; they looked for her everywhere. But nobody mentioned the dead fish, and the children were too little to tell a tale. The incident became old news. They never found the girl. The best they could hope for her was that she’d run off with some sweetheart, and made a life elsewhere. Odd, though; she’d been such a good lass.

After that, it became more difficult to get to sleep. Riona stayed in the chest. I could imagine her small eyes looking at me, looking in the darkness, telling me truths about myself with never a word spoken. I did not want to hear what she might have to say. I did not want to think about anything in particular. I knew a lot of mind games, tricks Father had shown me for focusing the concentration, strategies for shutting out what was not wanted. But now, none of them seemed to work. Instead, my mind repeated three things, over and over. My grandmother’s voice saying, Scruples, Fainne? Darragh, watching as I made the fire with my pointing finger. Darragh frowning. You’re a danger to yourself. And a little image of a red-haired girl, weeping and weeping, frenzied with grief, eyes squeezed shut, hands clutching her head, nose streaming, voice hoarse and ragged with sobbing. She, of them all, I wanted out of my mind. I could not bear to witness so wild a display of anguish. It made me want to scream. It made me want to cry, I could feel the tears building up in me. But our kind do not weep. Stop it! Stop it! I hissed, willing her away. Then she raised her blotched and tragic face to me, and the girl was myself.

After an endless winter and a chill spring, summer came and the travelling folk returned to the cove. I passed my fifteenth birthday. This year, when I might have roamed abroad free of Father’s restrictions, I did not climb the hill to see the long shadows mark out the day of Darragh’s arrival. But I heard the sweet, sad voice of the pipes piercing the soft stillness of dusk, and I knew he was here. Part of me still longed to escape, to make my way up to the secret place and sit by my friend, looking out over the sea, talking, or not talking as the mood took us. But it was easy, this time, to find reasons not to go. Most of them were reasons I did not want to think about, but they were there, hidden away somewhere inside me. There was that girl, and what I had done. It didn’t seem to matter that my grandmother had made me do it; it didn’t seem to make a difference that I had intended only to scare her, that I had been prevented from changing her back in time. It was still I who had done it, and that made me a murderer. I knew what I had done was an abuse of the craft. And yet, all that I had, all that I was, I owed to my father. To save him, I must be prepared to do the unthinkable. I had shown myself strong enough. But I did not want anyone to ask me about it. Particularly Darragh. And there was another, even more compelling reason: something my grandmother had said one day.

‘There’s a further step,’ she’d told me. ‘You did well. You did considerably better than I expected, in terms of the end result. But it’s easy to tamper when you hate; easy enough, when you don’t care. You may need to do more than that. Tell me, Fainne, is there anyone who is a special friend? Anyone you are particularly fond of?’

I thought very quickly, and blessed my grandmother’s failure to master the skill of mind-reading.

‘Nobody,’ I said calmly. ‘Except Father, of course.’

Grandmother grimaced. ‘Are you sure? No friends? No sweetheart? No, I suppose not. Pity. You do need to practise that.’

‘Why? Why should I? What do you mean?’

She sighed. ‘Tell me, what things are most important to you?’

I framed my answer with care. ‘The task I have been set. That’s all that is important.’

‘Mm. Seems easy, doesn’t it? You go to Sevenwaters, you insinuate your way into the household, you work your magic, and the task is complete. But what if you become friends with them? What if you like them? It may not be so easy then. That’s when the real test of strength begins. These folk are closely tied with the Túatha Dé, Fainne. You will not hurt one without wounding the other.’

‘Like them?’ My amazement was quite genuine. ‘Become friends with the family that destroyed my mother, and took away my father’s dreams? How could I?’

‘You’d be surprised.’ Grandmother’s tone was drily amused. ‘They’re not monsters, for all they did. And you’ve encountered few folk here, shut away with Ciarán at the end of the world. He did you no favours by bringing you to Kerry, child. You’ll need to be very canny. You’ll need to remember who you are, and why you’re there, every moment of every day. You cannot afford to relax your guard, not for an instant. There are dangerous folk at Sevenwaters.’

‘How will I know who –?’

‘Some will be safe. Some are harmless. Some have the power to stop you, if you give yourself away. That’s what happened to me. See that it doesn’t happen to you, because this is our last chance. You’ll need to beware of that fellow with the swan’s wing.’

‘What?’ Surely I had not heard her properly.

‘He’s the danger. He’s the one who can cross over and come back when it suits him. Watch out for him.’

I was eager to know what she meant. But try as I might, she would tell me no more that afternoon. Indeed, she seemed suddenly in a very ill temper, and started to punish me with sharp wasp-like stings for each small error in the casting of a spell of substitution. It became necessary to concentrate extremely hard; too hard to ask awkward questions.

I learned about pain that summer. My grandmother’s earlier tricks were nothing to the punishments she inflicted on me when she thought me defiant or stubborn, when she caught me dreaming instead of applying myself to the task in hand. She could induce a headache that was like the grip on an earth-dragon’s jaws, an agony that turned the bowels to water and drained whatever will I might once have summoned to aid me. She could pierce the belly with a thousand long needles, and cause every corner of the skin to itch and burn and fester, so that one screamed for mercy. Almost screamed. She knew I was young, and she would stop just before the torture became unbearable. What she thought of my strength of will she never said. I endured what she did, since there was no choice. My father could not have known she would treat me thus, or he would never have left me to her mercies. I learned, and was afraid.

She showed me, one night, a vision that struck a far deeper terror in me.

‘Just in case,’ she said, ‘you think to change your mind once you are gone from here. Just to erase that last little glint of defiance from your eyes, Fainne. You think I lied to you, perhaps; that this is all some kind of elaborate fantasy. Look in the coals there, where the flame glows deepest red. Slow your breathing, and shut out all else as you have been taught to do. Look hard and tell me what you see.’

But there was no need to put it into words. She must have read in my face the horror I felt as I stared into the fire and saw the tiny image of my father, his strong features contorted, his body twisted with pain, his chest racked with a coughing that seemed fit to split him asunder. Blood dribbled from his gasping mouth, his hands clutched blindly at the air, his dark eyes stared like a madman’s. My whole body went cold. I heard myself whispering, ‘Oh no, oh no.’ I might have begged her then, if I had had the strength to find words for it.

‘Oh, yes,’ Grandmother said, as the vision faded and I slumped back to crouch on the rug before the hearth. ‘It matters nothing to me if this is my son or a stranger, Fainne. All that matters is the task in hand.’

‘M – my father.’ I stammered. ‘Is he –?’

‘What you see is not now, it is the future. A possible future. If you want a different picture, it is up to you to ensure you obey my orders and perform what is required of you. Defy me, and he’ll die, slowly. You’ll do as I tell you, and you’ll keep your mouth shut about it. I hope you believe me, child. You’d be a very silly girl if you didn’t. Do you believe me, Fainne?’

‘Yes, Grandmother,’ I whispered.

The warm days passed, and the voices of children floated up on the summer breeze and made their way, laughing and shrieking, into the shadowy inner chambers of the Honeycomb. The curraghs sailed out of the cove in the dawn and returned at dusk, laden with their gleaming catch. Women mended nets on the jetty, and brown-skinned lads exercised horses along the strand, high-stepping over the mounded seaweed. I lay awake, night after night, listening to the distant lament of the pipes. Though Fiacha came and went, there was no sign at all of Father, and I began to fear I might never see him again. That hurt me terribly; and yet I did not want him to see what I was becoming, to witness my ill-use of the craft, and so in a way his absence was a relief. I hoped he would never have to learn the truth, that in sending me forth he sacrificed his only child to the most foolhardy and impossible of quests, where his own life was the price of failure. As for Grandmother, to her I was no more than a finely tuned weapon, a tool many years in the fashioning, which she would now employ for a purpose of such grandeur I still struggled to come to terms with it.

The summer was nearly ended. Grandmother had made practical preparations of a sort. My small storage chest now held two gowns of a slightly better standard than my usual garb of old working dress and serviceable apron. I had a new pair of indoor shoes as well as my walking boots. A man had made them specially, muttering to himself as he took measure of my misshapen foot. This was a trial. I would have blistered the cobbler’s fingers for him; but I needed the shoes.

I had not asked my grandmother how I was to travel to Sevenwaters. It was a long way, I knew that because Darragh had told me; nearly the length and breadth of Erin. But I had no idea how many moons such a journey might take. Perhaps my grandmother would work a spell of transportation, and send me north in an instant with my baggage by my side. In the end there was no need to ask, for one day Grandmother simply announced that it was time to go.

‘You’ll travel north on Dan Walker’s cart,’ she said, checking the strap which fastened my storage chest. ‘Very practical, if not altogether stylish.’

‘Practical?’ I echoed in dismay. ‘What’s practical about it?’

‘You’ll arouse a great deal less suspicion if you turn up with the travelling folk,’ she said drily, ‘than by manifesting yourself in your uncle’s hall amidst a shower of sparks. This way nobody’ll notice you. What’s one more lass amongst that great gaggle of people? Not nervous, are you? Surely I’ve worked that out of you by now. Use the Glamour if you must. Be what pleases you, child. These folk are only tinkers, Fainne. They’re nothing.’

‘Yes, Grandmother.’ Her words did little to settle the nervous churning in my stomach. I knew I must be strong. The task I undertook for my grandmother, her terrible work of vengeance against those who had slighted our kind, must be pursued with the utmost strength of purpose. My father’s very life was in my hands. I could not fail. I would not fail. Still, I was barely fifteen years old, tortured by shyness and quite unused to the world at large. It was this, I suppose, that made me such a subtle weapon. I must have seemed as innocuous as some little hedge creature that scuttles for cover at any imagined danger.

I took my leave of Grandmother. If she still harboured any doubts, she kept them to herself.

‘I almost wish I was coming with you,’ she sighed, and for an instant I caught a glimpse of that other manifestation she was fond of, an alluring, curvaceous young creature with auburn hair and pearly skin. ‘There must be fine men in those parts still, though there’ll never be another Colum. And I could still cast my net, make no doubt of it.’ Then, abruptly, she was herself again. ‘But I can see it wouldn’t do. They’d know me, Glamour or no. The druid would know me. So would that other one. This is your time, child. Remember what I’ve taught you. Remember what I’ve told you. Every little thing, Fainne.’

‘Yes, Grandmother.’

We walked out of the Honeycomb to the point where the cliff path stretched ahead all the way down to the shore and along to the western end of the cove, where Dan Walker and his folk would be making ready for departure. And there, dark-cloaked, ashen-faced, stood my father, staring silent out over the sea. My heart gave a great lurch.

‘I might walk down with you,’ Grandmother said. ‘See you on your way.’

It’s not easy to cast a spell over a fellow practitioner of the art. You need to be quick or you’ll encounter a barrier or counter-spell, and your efforts will be entirely wasted. This was exceptionally quick. In an instant, without so much as a glance at each other, both Father and I threw nets of immobility over Grandmother, so that she was held there in place from both left and right, feet rooted to the rock, mouth slightly open, eyes frozen in piercing annoyance.

‘She’ll be angry,’ I remarked to Father as we set off down the path, he carrying my small wooden chest on his shoulder, I clutching a roll of bedding for the journey. Fiacha flew overhead.

‘I’ll deal with it,’ Father said calmly. I glanced at him and thought I detected a shadow of amusement in his dark eyes. But he was thin, so thin, and he seemed far older than he had last autumn, his cheeks hollow, his severe mouth bracketed by new lines of pain. ‘Now, Fainne, we don’t have long. Are you well? This will have been a difficult time for you, a time of great change. It was hard for me to leave you thus; hard but necessary. Are you ready for this journey now, daughter?’

I picked my way with caution down the narrow, steep pathway. It had been raining, and the surface was treacherous. Questions raced through my head. How could you let your own mother do this to you? And, Why didn’t you tell me the truth? And, strongest of all, Will I ever see you again? I could not ask any of them, for Grandmother would know, and it would be my father who was punished for it. I longed to throw my arms around him and blurt out the whole truth, and be a child again in a world where the rules made sense. I could not tell him anything.

‘Yes, I’m ready,’ I said, feeling an odd sensation behind my eyes, as if I were about to cry.

‘Sure?’

‘Yes, Father.’

So we walked on in silence, and it seemed to me that although we walked quite slowly, as if reluctant to reach the end, we were very soon down on the level track that skirted the strand, and Dan and Peg and the jostle of bright-clad folk were in sight along the path.

‘Father,’ I said abruptly.

‘Yes, Fainne?’

‘I want to say – I want to thank you for being such a good teacher. To thank you for your wisdom and your patience – and – and for letting me find things out for myself. For trusting me.’

He said nothing for a moment. When he did speak, his voice was a touch unsteady. ‘Fainne, it is difficult for me to say this to you.’

‘What, Father?’

‘I – you need not go, if you do not wish to do so. If, in your heart, you feel this way is not for you, you have that choice.’

‘Not go?’ My heart thumped. Now, now that it was too late, he told me I could stay, and I was forbidden to say yes. I cleared my throat. I had never lied to him before. ‘When we have come so far, not do this for you? Do I not owe it to my mother to go back to Sevenwaters and become what she would wish me to be? Surely I must go.’ And, oh, how I longed to tell him I would give anything to stay with him in Kerry, and have things be as they once were. But he was my father, and for his own sake I must find the courage to leave him.

‘I wished – I simply wished you to understand that ultimately, what occurs, what develops, is for you to determine. And – and, Fainne, this may be a far greater, a far more momentous unfolding of events than either you or I have ever envisaged. So important that I would not dare put it into words for you. We are what we are by birth and by blood. Over that, we have no control. We cannot break the mould of our kind. But one always has the choice to practise the craft, to one end or another, or to stand aside. That choice you do have, daughter.’

I stared at him. ‘Not practise the craft? But – but what else is there?’

Father made no reply, simply gave a little nod. His expression remained impassive. He had ever been a master of control. We began to walk again, our last walk together around the cove, with the plumes of spray dashing the Honeycomb behind us, and the remote cries of the gulls above us, and ahead, Dan Walker advancing towards us, a hand reached out in greeting and a grin on his dark, bearded face.

‘Well, Ciarán. You’ve brought the lass, I see. Give that bundle to Darragh, young lady, and we’ll see you settled on the cart. All ready to go?’

I nodded nervously, staring at the ground. I did not even look at Darragh as he came up and plucked the roll of bedding out of my hands. The wooden chest was loaded unceremoniously onto one cart, and I found myself hoisted up on the other one, to be seated next to Peg’s friend, Molly, and several small girls with rather loud voices. Father stood alongside, and I thought he seemed even paler than before, if that were possible.

‘I’ll take good care of her, Ciarán,’ said Dan as he leapt up on the first cart and took the reins in his hand. ‘She’ll be safe with us.’

Father nodded acknowledgement. At the back of the assembled folk the lads were herding ponies into line, whistling sharply. Dogs added their excited voices. Fiacha retreated to a vantage point atop a dead tree, and the gulls scattered.

‘Well,’ said Father quietly. ‘Goodbye, daughter. It may be a long time.’

Now that the final parting was come, I could hardly speak. The task ahead was so daunting it could hardly be imagined. Change the course of a battle. Beat the Fair Folk at a game they had been practising for more years than there were grains of sand on the white shore of the cove. A momentous unfolding of events … I must complete the task my grandmother had begun, I must do it at any cost, to repay him for the years of patience and the priceless gift of knowledge.

‘Goodbye, Father,’ I whispered, and then Peg called to the horses, and gave a practised flick of the reins, and we were off. I looked back over my shoulder, watching my father’s still figure growing smaller and smaller. I remember colours. The deep red of his hair. The ashen white of his stern face. The long black cloak, a sorcerer’s cloak. Behind him the sea swept in and out, in and out, and the sky built with angry clouds, slate, purple, violet, dark and mysterious as the hide of some great ocean creature. A wind began to stir the beaten branches of the low bushes that bordered the track, and the little girls huddled together under their blanket, giggling and whispering behind their hands.

‘It’ll pass,’ said Peg to nobody in particular.

‘All right, lassie?’ queried Molly rather awkwardly. I gave a stiff nod, and winced as the cart went over a rock. Then we rounded a bend in the road, and Father was gone.