Читать книгу Ask Not What I Have Done for My Country, Ask What My Country Has Done for Me - Julio Rodarte - Страница 11

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

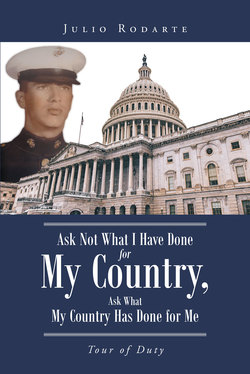

ОглавлениеEnlistment in the United States Marine Corps

It was January 13, 1969, that I joined the US Marine Corps along with four other friends from the nearby communities. This is a story that is brutally open and honest. Vietnam is the secret world, the inner sanctum of a warrior, a place unknown to most, a hidden world seldom spoken of to the uninitiated, yet a time-honored world in which we live every moment of every year. War after war, there will always be warriors, and all warriors share the same battleground, and we are caught in two very different and conflicting worlds. As we became Marines, each of us left behind the comforts and safety of our country to travel halfway around the world to experience the horrors of war, and yet within it, we found the true meaning of trust, honor, friendship, and loss. As our tours of duty ended, we returned back to the world only to find our torment continuing with the painful memories of how life once was, and yet could never be the same again. Due to my own military background, I have kept my primary focus on learning how to deal with post-traumatic stress and have learned that we all combat Vietnam veterans have one thing in common. This story recounts many of my own experiences, beginning as a Marine combat rifleman with India Company, Third Battalion, Fifth Marines in and around An Hoa, South Vietnam. As I got in country, I had to quickly learn first to survive combat and, for fifty years, have learned to survive life. To accept dishonor, accept the fact that my valor was stolen by my company commander. Where necessary, I use harsh language, which was common among us in Southeast Asia.

For those of you who have love ones and friends, I hope that you have taken the time to understand what we have gone through and understand that we have come back to the “world” from war forever changed. A new day out in the “bush” was a blessing and never knowing what the rest of the day brought forth. Each day, I never knew if I was going to die or perhaps, at best, be severely wounded. This is what we live through each day that we were in a combat operation.

We truly want to feel normal. We want to be like we were and what most people would like us to be again, but it is impossible. We have changed forever.

For a combat Vietnam veteran walking off the battlefield, the journey of life becomes very lonely, very painful. All of us ask only for someone to care, to understand our pain, and to love us as we are, who gave all we had to protect what we hold sacred, our country, our home, and our loved ones—la famila, la tierra, y la patria. We loved those we left behind, more than they will ever know. I ask of you to open your hearts to us, to allow us to be a part of your world that we would willingly die to protect. We will never be like we were as much as we try to. Accept us for who we have become, for what we have sacrificed for you and this great nation.

Joining the Marine Corps

It was the morning of January 13, 1969, that my parents learned that I was joining the corps. It was my decision and my decision only, and I didn’t want anybody interfering. I had decided to join the Marine Corps for two years and continue my education. My mother had no idea that I was joining the service; she couldn’t understand why I was making this decision. She knew that the Selective Service was drafting teenagers if they didn’t have a school deferment. I told her I was not going to wait to get drafted and that I was volunteering. My father didn’t say much; he acknowledged my decision. Yet after my return from the war, he mentioned to me that I was a fool for enlisting. My response was, had I not joined by my own free will and gone against my will, we probably would not be having this conversation.

The war was not an issue for me, until I entered the Marine Corps in 1969. Three years of carnage and a personal vulnerability to the draft at the very height of the war had made little impression on me. I doubted I even knew where Vietnam was. Nor did I much care. After all, I recall, I was eighteen years old, fresh out of high school, and having a good time. The draft was something you always thought of, but I never thought of Vietnam. All I saw was a little bit on the news. Hell, when I was eighteen years old, who watches the news? I was more interested in going out and having a good time.

Arguably, few young men just out of high school had the maturity or experience to assign a value to our lives or to understand just how fleeting life could be. War is a concept that can be understood only after the fact, and such understanding seems impossible to impart to those who have not shared an equivalent experience.

Military service attracts young people in peacetime and time of war for reasons both personal and patriotic. The majority of men who were called to serve in Vietnam went dutifully. I volunteered with the intention of serving in combat; others enlisted for precisely the opposite reason. But somewhere between the extremes of aggression and avoidance lay the personal motivations that attracted nearly eight million Americans to enlist during the Vietnam era.

Vietnam was not a concern to those who entered the service prior to the summer of 1965, largely because full-scale American participation had not yet begun. Theirs were peacetime reasons for joining the military. Consequently, when the first American infantry unit deployed to Vietnam in 1965, the majority of the men in their ranks were volunteers.

The military served as a form of social welfare for some, a relief mechanism for those in need of opportunity. But it was not the stellar opportunity afforded by the minorities into the ranks; rather, it was a lack of chances for employment elsewhere that channeled me into uniform. Many of us young men, minority members as well as whites, enlisted as a means of securing a better future and acquiring an education through the Montgomery GI Bill. Although it is common to assume otherwise, the most serious inequities between those who served in combat in Vietnam, and those who did not were based on social and economic distinctions rather than racial ones.

Unfortunately, minorities in the United States were more likely to be poor; and the poor, as well as the poorly educated—regardless of race—found their way into the service and into combat at perhaps double the rate of their more affluent neighbors. The military was also a place where a young man might find some personal direction and self-discipline. For us young men, enlistment did not always indicate volunteerism. Some of the so-called volunteers were pressed into joining by a magistrate or judge who saw military service as a way to rehabilitate social misfits and petty criminals. These individuals had a choice to either do prison time or military time, and most chose to enlist in the United States Marine Corps.

The majority of us Vietnam veterans are proud of what we did for our country; our greatest pride is in what we endured for one another. While some of us now believe that we were victimized, those of who volunteered can blame nothing more than our own innocence or our involvement in the war. I had not been duped or coerced by double-taking recruiters. I had simply trusted our government, believed the rhetoric, and stepped forward because, for whatever reason, that was the direction I wanted to go. I believed in my government and my country, and I was willing to do the ultimate “por me patera.”

There was a widespread belief in the country that even if the war was unjust or unwinable, America could not simply turn tail and run. The war’s goals were honorable. For some, the conviction still exists that while the war itself was militarily mismanaged and politically doomed from the start, the ideals for which we fought were the right ones all along. I was determined to be one of the best, and I was not going to give up. I would not lose hope and determination and follow my instincts.