Читать книгу Curtain Up: Agatha Christie: A Life in Theatre - Julius Green - Страница 11

Behind the Scenes

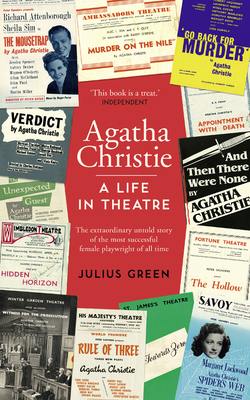

ОглавлениеThis is the story of the most successful female playwright of all time. She also wrote some books.

Agatha Christie (1890–1976) is universally acknowledged as the world’s best-selling novelist, and yet the significance of her contribution to theatre has been largely overlooked by historians. This despite the fact that she is responsible for a repertoire of work that enjoyed enormous global success in her own lifetime and continues to do so more than forty years after her death. She not only holds the record for the world’s longest-running theatrical production, but is also the only female playwright to have had three of her works running in the West End simultaneously. Her first attempts at playwriting date from around 1908 and her last completed play premiered in 1972. Nine of her plays opened in the West End in the 1940s and 1950s alone, and two of them were big hits on Broadway. For Christie, theatrical success arrived relatively late in life; it brought her much pleasure and, despite her legendary shyness, she enjoyed the company of theatrical people and relished their eccentricities.

From the point where she finally broke through as a playwright in the 1950s, it is clear that Christie continued to regard writing books as her day job, but that she found true creative fulfilment in her work for the stage. In her autobiography she notes:

Of course I knew that writing books was my steady, solid profession. I could go on inventing plots and writing my books until I went gaga … writing plays seemed to me entrancing simply because it wasn’t my job, because I hadn’t got the feeling that I had to think of a play – I only had to write the play that I was already thinking of. Plays are much easier to write than books, because you can see them in your mind’s eye, you are not hampered by all the description that clogs you so terribly in a book and stops you getting on with what’s happening. The circumscribed limits of the stage simplify things for you. You don’t have to follow the heroine up and down the stairs, or out to the tennis lawn and back, thinking thoughts that have to be described. You only have what can be seen and heard and done to deal with. Looking and listening and feeling is what you have to deal with.1

In a 1951 article on Christie, The Stage newspaper reported that she found writing plays easier than writing books because ‘With a play you can go straight to your plot and characters and you have not to deal with the problem of describing scenes and the movements and habits of people. If you are at all successful, all this appears automatically through your characters and the action in which they are involved.’2 And, in an interview for the BBC Radio Light Programme in 1955, she once again stated that ‘Of course writing plays is much more fun than writing books … you must write pretty fast, keep in the mood and keep the talk flowing naturally.’3

Some commentators have interpreted such remarks as implying that, whilst writing books was Agatha Christie’s profession, writing plays was simply her hobby. My own view is that, for a writer who had a real aptitude for dialogue and who, by her own admission, felt hampered by ‘description’, playwriting was her true vocation. And her determined, twenty-year struggle to gain recognition as a dramatist bears witness to this. Like most playwrights, Agatha Christie has her good and her bad days but, speaking as a theatre practitioner rather than an academic, it seems to me that she is both a master of her craft and a unique and witty voice with a great deal to say about the human condition. Actors always seem to enjoy engaging with her characters and find much in them to relate to, belying the popular misconception that they are thinly drawn caricatures. Her work is laced, whether consciously or not, with echoes of the other great playwrights of the era, and some of the most celebrated actors of the day appeared in her plays.

So why has history been so unkind to Agatha Christie, playwright? At the height of her popularity in the 1950s the dominant producing force in the West End was Binkie Beaumont, but Christie’s most enduring working relationship was with Peter Saunders, a rival impresario who was openly critical of the monopolistic tendencies of the Beaumont empire. So, despite her popular success, Christie was notable for working outside the established (and at times fearsomely ruthless) West End oligarchy of the day; a fact that makes her achievements all the more remarkable. As a doyenne of the ‘well-made play’ she remained delightfully untouched by the Royal Court revolution and consequently does not even feature in the vocabulary of those academics for whom the history of twentieth-century British playwriting started with Look Back In Anger in 1956. She thus occupies a unique position as a playwright, outside both the prevailing theatrical culture and its counter-culture; and her theatrical vocabulary suits the historians of neither.

Another very straightforward reason for the neglect of Christie as a playwright is continued confusion over the authorship of the plays credited to her. As well as her own work for the stage there have been a number of second-rate adaptations of her novels by third parties; and this, combined with the enduring success of third-party film and television adaptations, has led to an assumption that the plays credited to her were not from her own pen. There is an immediate and obvious qualitative difference between Christie’s own work for the stage and that of her adaptors, but the staging of a number of such works in her own lifetime, and several more since, has inevitably diluted her own stock as a playwright. Christie herself was unequivocal on the subject, repeatedly expressing her displeasure at her stage adaptors’ work: ‘Several books of mine were dramatised by other people and they all dissatisfied me intensely,’ she told the Sunday Times in 1961.4 Ironically, though, whilst arguably initially hindering her own development as a playwright, the adaptors’ efforts provided her with an entrée to the world of theatre and its practitioners, where she became a willing student and gained the confidence to promote her own work: ‘I think what started me off was my annoyance over people adapting my books for the stage in a way I disliked.’5 Certainly, she is the only playwright I can think of whose reputation has had to contend with the truly bizarre obstacle of a body of work for the stage penned by others but promoted to the public and the critics in her name.

And then there is the question of collaboration. Playwriting is often a shared undertaking, and writers from Shakespeare to Brecht to David Edgar have worked with others in the preparation of their scripts. There can be no doubt that one of the things that most attracted Christie to the stage was the collaborative nature of the process, enabling her as it did to exchange ideas with others in a way that her largely solitary work as a novelist did not. She was a willing and adept participant in script discussions, either as a commentator on other people’s adaptations of her novels or as a playwright herself attempting to address the concerns of producers, directors and actors. Despite the patronising claims of certain directors about the level of their own input, the fourteen full-length plays and three one-act plays that were premiered on stage in Christie’s lifetime, and which carry her name as sole playwright, are indisputably her own work. She only ever incorporated the suggestions of others up to a point, and always remained in control of the script development process. And when she was convinced that she was in the right she was legendarily immovable. Ironically, her own highly accomplished adaptation of one of her short stories was appropriated wholesale by an ‘adaptor’ without so much as an acknowledgement of her own dramatisation as source material. And, conversely, she had very little to do with the only script for which she is actually credited as co-adaptor. In such cases Christie herself acted in good faith at the behest of agents and producers, but it doesn’t help when it comes to establishing the extent of her own contribution to the dramatic canon that bears her name.

There is also perhaps a misconception that Christie exploited her reputation as a novelist to promote her career in the theatre, and that her theatrical successes were in some way dependent on the success of her books. If anything, as we shall see, the opposite was the case, and the expectations raised by the popularity of her detective fiction frequently hampered her progress as a playwright and prejudiced critical opinion against her work on the stage. Whilst her producers inevitably attempted to capitalise on her existing fan base, the adaptations of some of her best-selling novels proved to be critical and box office disasters, and theatregoers repeatedly demonstrated themselves to be more than capable of judging her work for the stage on its own merits. Christie’s success as a playwright was exceptionally hard-won and, far from resting on her laurels as a popular novelist, she consistently dedicated herself to honing her craft, observing and willingly learning from the numerous leading theatrical practitioners with whom she worked. In any case, Christie was writing at a time when combining careers as a novelist and a playwright was not uncommon; amongst the contemporary female playwrights who did so were Clemence Dane, Margaret Kennedy, Enid Bagnold, Dodie Smith and Daphne du Maurier. Christie was simply both a more successful novelist and, ultimately, a more successful playwright than any of them. And, for those who carp that her plays were simply adaptations of existing works, it is instructive to note how far these adaptations diverge from their source material and that, amongst her full-length plays, there are nine totally original works, six of which were premiered in her lifetime. Christie herself said, ‘I prefer to write a play as a play, that is rather than to adapt a book.’6

Christie was passionate about theatre and was deeply involved in the processes of making it. She attended and contributed to rehearsals, and her delightful ‘author’s notes’ at the front of some of the published editions of the plays show her engaging with everything from the mechanics of creating the effect of a lift ascending and descending in Appointment with Death to the problems associated with the unusually large dramatis personae of Witness for the Prosecution and the ‘ageing’ of actors and multiple locations in Go Back for Murder. She was very aware of the practicalities of putting on a play, favouring single sets and relatively small casts (Appointment with Death and Witness for the Prosecution are notable exceptions), and this partly accounts for her enduring popularity with cash-strapped repertory theatres and touring companies over the years, and the consequent law of diminishing returns in terms of both production values and credibility within the theatre community.

Born in 1890, for the first ten years of her life Agatha was a Victorian; Gladstone became Prime Minister for the fourth time shortly before her first birthday. As a teenager and a young woman she was an Edwardian. She waved husbands off to both world wars, and women got the vote on the same basis as men when she was thirty-eight. In 1969 she watched man land on the moon on television, and when she died in 1976, Harold Wilson was Prime Minister. Her first success as a novelist came when she was thirty; but although she started writing plays as a teenager, none of her work was staged until she was forty, and her playwriting career didn’t really take off until she was in her sixties. This is an interesting inversion of the timeline of Noël Coward’s career; Coward and Christie were contemporaries, but his success as a playwright came much earlier in life and reached its pinnacle in the Second World War with Blithe Spirit and Present Laughter, just as Christie was experiencing her first West End hit with Ten Little Niggers. (The history of this play’s problematic title is examined later in this book.)

All but one of Christie’s plays are firmly set in the period in which they were written, and they resist any attempt at updating in just the same way that the work of Noël Coward does. Although the moral dilemmas faced by the characters and their guilt, obsession, love and jealousy are timeless, their behaviour and interactions are very much a function of the social mores of the time in which each play is set; not to mention the fact that modern communications technology would severely compromise key elements of the plotting. The stakes are raised in several of the storylines by the ever-present threat of the hangman’s noose; particularly in Verdict, where the existence of the death penalty clearly informs the protagonist’s decision not to turn the murderer over to the police, and in Towards Zero, where it accounts for an extraordinary plot twist. The acceptability of smoking provides a continuous subtext of cigarettes, pipes and cigars both as a form of social interaction (offering someone a cigarette can be as good as a chat-up line) and to underscore key moments of tension. A nervous character will reach for a cigarette and a pipe smoker is usually to be trusted.

But it would be a mistake to assume that the society reflected in the majority of Christie’s stage work is a halcyon one of pre-war vicarage tea parties. Ironically, this relatively elderly woman, whose upbringing was defined by the mores of the previous century and whose frame of reference is generally assumed to be that of the pre-war era, found lasting fame as a playwright in the decade when ‘angry young men’ were allegedly redefining the theatrical playing field at the Royal Court. Christie did not live a cocooned middle-class life. She was adventurous, widely travelled and politically aware, and encountered people of all classes and cultures. She worked in a hospital dispensary during the First World War (gaining a comprehensive knowledge of poisons in the process), was one of the first people to surf standing up on a surfboard (whilst visiting South Africa) and made use of recent changes in the law to divorce her cheating first husband, Archie Christie, in 1928. Her work spans a century of massive social and political change and this does not go unacknowledged within it, from The Hollow with its crumbling aristocracy facing up to the loss of empire to the overtly political challenge to the conservative orthodoxy represented by Alderman Higgs in Appointment with Death, the ‘not a Red, just pale pink’ Miss Casewell in The Mousetrap, the post-war suspicion of foreigners in Witness for the Prosecution and the persecuted East European immigrants at the centre of Verdict.

Whilst the received wisdom is that Christie’s novels are to a certain extent formulaic, and much scholarly time has been devoted to analysing these alleged formulae, the same most definitely cannot be said of her work as a playwright, and it almost seems that she found herself enjoying greater freedom of expression as a writer in this genre. A repertoire encompassing the edge-of-your-seat chiller Ten Little Niggers, the definitive courtroom drama Witness for the Prosecution, the Rattiganesque psychological drama Verdict and the ‘time play’ Go Back for Murder can hardly be described as formulaic and there is no such thing as a ‘typical’ Agatha Christie play. Despite the enduring perception of her work as little more than an extended game of Cluedo, Christie’s plays tend to be character-led rather than plot-led, and she clearly relishes entrusting the entire momentum of the story-telling to the voices of her ever-colourful dramatis personae. Her dialogue fairly trips off the tongue and is spiced with witticisms and observational comedy frequently worthy of Wilde. In her plays the detectives and police inspectors are usually relegated to minor roles, with the solving of a crime taking second place to the human drama that is being played out. It is as if we come closer to what Christie wants to say as a writer without the dominating presence of Poirot and Marple. With the exception of Poirot’s appearance in Black Coffee, the first play of hers to be produced (in 1930), neither character features in any of her own stage plays, and indeed she removed Poirot from the storyline when undertaking her own adaptations of four of the novels in which he appears, maintaining, doubtless correctly, that he would pull focus on stage.

Explorations of guilt, revenge and justice loom large in Christie’s stage work and are timeless subjects that go back to the very dawn of playwriting, but although the concept of justice and the many forms that it can take is central to many of her plays, the image of the policeman leading away the guilty party in handcuffs is rarely part of her theatrical vocabulary. An inability to escape the past is a recurring theme, and man’s infidelity is often the catalyst for its exploration, a frequently used storyline that some have attributed to the philandering of Christie’s own first husband. In Christie’s work for the stage, the murder itself is usually nothing more than a plot device to move forward the action and to set the scene for Christie’s exploration of the human condition and the dilemmas faced by her characters. ‘Who’ dunit is far less important than ‘Why’.

Agatha was a regular theatregoer from childhood and engaged in theatrical projects from an early age, was hugely theatrically literate and drew on a broad frame of reference from Grand Guignol to Whitehall farce, all of which can be seen in her work. But her lifelong passion was for Shakespeare, and her theatrical vocabulary was defined in particular by an enjoyment and understanding of his works, gained as an audience member and a reader rather than a scholar. In a 1973 letter to The Times she wrote: ‘I have gone to plays from an early age and am a great believer that that is the way one should approach Shakespeare. He wrote to entertain and he wrote for playgoers.’7 And in her autobiography she says,

Shakespeare is ruined for most people by having been made to learn it at school; you should see Shakespeare as it was written to be seen, played on the stage. There you can appreciate it quite young, long before you take in the beauty of the words and the poetry. I took my grandson, Mathew, to Macbeth and The Merry Wives of Windsor when he was, I think, eleven or twelve. He was very appreciative of both, though his comment was unexpected. He turned to me as we came out, and said in an awestruck voice, ‘You know, if I hadn’t known beforehand that that was Shakespeare, I should never have believed it.’ This was clearly meant to be a testimonial to Shakespeare, and I took it as such.8

Agatha and her grandson particularly enjoyed the knockabout comedy of The Merry Wives of Windsor:

In those days it was done, as I am sure it was meant to be, as good old English slapstick – no subtlety about it. The last representation of the Merry Wives I saw – in 1965 – had so much arty production about it that you felt you had travelled very far from a bit of winter sun in Windsor Old Park. Even the laundry basket was no longer a laundry basket, full of dirty washing: it was a mere symbol made of raffia! One cannot really enjoy slapstick farce when it is symbolised. The good old pantomime custard trick will never fail to rouse a roar of laughter, so long as custard appears to be actually applied to a face! To take a small carton with Birds Custard Powder written on it and delicately tap a cheek – well, the symbolism may be there, but the farce is lacking.9

Agatha’s letters to her second husband, Max, during his wartime posting to Cairo are full of enthusiastic descriptions of her visits to the major Shakespearian productions of the day, including those presented by the Old Vic Company at the New Theatre, their London base towards the end of the war. Her critiques of the productions and the performances of the leading classical actors of the day, and her insightful interpretations of the characters’ motivations, display a comprehensive knowledge of the Shakespearian repertoire. She also shows a keen interest in Shakespeare’s craft as a playwright. Commenting on the fact that he did not devise original plots she says, of the era in which he wrote:

I think the playwright was rather like a composer – he had to find a libretto for his art (like a ballet nowadays). ‘I should like to do a setting of Hamlet, or my version of Macbeth etc.’ Inventing a story was not really thought of. ‘What is the argument?’ Claudius asks in Hamlet before the players begin. The argument was a set thing – you then exercised your art on it … I think plays tended to be loose on construction, because they incorporated certain ‘turns’ – like the music halls … He saw a play as a series of scenes in which actors got certain opportunities. Rather like beads on a necklace– the thing to him remained always individual beads strung together.10

Shakespeare’s portrayal of female characters particularly engaged Agatha – ‘All Shakespeare’s women are very definitely characterized – he was feminine enough himself to see men through their eyes’11 – and she was intrigued by Oxford academic A.L. Rowse’s disputed identification of the ‘Dark Lady’ of Shakespeare’s sonnets. Rowse, in turn, was an admirer of Christie; ‘We must not underrate her literary ambition and accomplishment, as her publishers did, simply because she was the first of detective story writers.’12 Meanwhile, Christie trivia buffs can spend many happy hours identifying the numerous Shakespearian references in the titles and texts of her works. To get the ball rolling, I will pose the question, what were the two plays she wrote that took their titles from Hamlet?

Agatha was as enamoured with the backstage world of theatre as she was with the performance itself. ‘I don’t think, that there is anything that takes you so much away from real things and happenings as the acting world,’ she wrote to Max in 1942.13 ‘It is a world of its own and actors never are thinking of anything but themselves and their lines and their business, and what they are going to wear!’ And she says in her autobiography, ‘I always find it restful to stay with actors in wartime, because to them, acting and the theatrical world are the real world, any other world was not. The war to them was a long drawn-out nightmare that prevented them from going on with their own lives, in the proper way, so their entire talk was of theatrical people, theatrical things, what was going on in the theatrical world, who was going into E.N.S.A. – it was wonderfully refreshing.’14 To Agatha Christie, whose imaginary world has offered a welcome escape for so many, the world of theatre offered one to her.

Agatha shared with her theatrical friends the excitements and disappointments of live performance – ‘Lights that do not go out when the whole point is that that they should go out, and lights that do not go on when the whole point is that they should go on. These are the real agonies of theatre’15 – and in particular the agonies of first nights:

First nights are usually misery, hardly to be borne. One has only two reasons for going to them. One is – a not ignoble motive – that the poor actors have to go through with it, and if it goes badly it is unfair that the author should not be there to share their torture … The other reason for going to first nights is, of course, curiosity … you have to know yourself. Nobody else’s account is going to be any good. So there you are, shivering, feeling hot and cold alternately, hoping to heaven that nobody will notice you where you are hiding yourself in the higher ranks of the Circle.16

Christie trivia buffs can again spend happy hours identifying the numerous theatrical references, characters and scenarios in her novels; I offer for starters 1952’s They Do It with Mirrors, in which Miss Marple is fascinated by the stage illusion involved in the creation of a production of a play that rejoices in the Christiesque title ‘The Nile at Sunset’. And it is no coincidence that disguise is a recurring plot device in her plays, a number of which feature characters who are impersonating someone else. This conceit accounts for Christie’s two greatest coups de théâtre, in The Mousetrap and Witness for the Prosecution; the latter is carried out with a high level of theatrical skill by a character who is a professional actress, in a plot twist with echoes of her 1923 short story, ‘The Actress’.17

Agatha Christie is herself one of the most written about of writers. Much of what has been published about her, however, engages either with the highly seductive imaginary world of her novels or with endlessly re-examined elements of her personal life; even those writers who do make a serious attempt to place her work in a historical and literary context tend to overlook her contribution as a dramatist. Alison Light’s persuasive study of Christie’s work as an example of ‘conservative modernity’ in Forever England (1991) focuses on the inter-war period and so can be excused for overlooking her plays. But other serious assessments of her work, from Merja Makinen’s Agatha Christie: Investigating Femininity (2006) and Susan Rowland’s From Agatha Christie to Ruth Rendell (2001) to Gillian Gill’s Agatha Christie: The Woman and her Mysteries (1999) and Agatha Christie in the Modern Critical Views series (edited by Harold Bloom; 2001), are united in their neglect of her work as a playwright. Ironically, many of the writers concerned may well have found an engagement with Christie’s work for the stage to have been beneficial to their arguments.

An honourable exception is Charles Osborne’s 1982 book The Life and Crimes of Agatha Christie. Osborne, a theatre critic and former literature director of the Arts Council, is less academic in his tone than the writers listed above, but is diligent in affording Christie’s dramatic work equal prominence with her novels. Other than Osborne’s book, the only significant overviews of Christie’s plays in the context of appraisals of her own work are in J.C. Trewin’s lively and opinionated contribution to Agatha Christie; First Lady of Crime (edited by H.R.F. Keating; 1977) and a chapter in Peter Haining’s workmanlike Murder in Four Acts (1990). Two histories of crime drama, Marvin Lachman’s The Villainous Stage (2014) and Amnon Kabatchnik’s epic, five-volume Blood on the Stage (2009–2014), each contribute some original research to the subject, and at least acknowledge Christie’s significance as a writer of stage thrillers if not as a playwright in a wider context. Several of the multifarious Christie ‘companions’ and ‘reader’s guides’ dutifully list the plays and recite the often inaccurate received wisdom about their origins and first productions (an honourable mention here to Dennis Sanders and Len Lovallo’s 1984 The Agatha Christie Companion, which is a cut above many of its competitors); but I have seen ‘encyclopedias’ of her characters which omit completely those which appear only in the plays.

Perhaps most saddening, though, is the fact that Christie has even been eschewed by feminist theatre academics such as those responsible for The Cambridge Companion to Modern British Women Playwrights (2000), meriting not so much as a footnote in the chapter covering the 1950s in a book that purports to ‘address the work of women playwrights in Britain throughout the twentieth century’. Whilst not notable for chaining herself to railings, Christie challenged the male hegemony in West End theatre more successfully than any other female playwright before or since. She took on her male contemporaries on their own terms, and in many respects beat them at their own game. She created a series of strong and memorable female protagonists of all ages, and any actress complaining that there are not enough substantial stage roles for women need look no further than her plays. Most disappointing is Maggie B. Gale’s West End Women (1996). Although Gale’s book, which covers the period 1918–1962, offers a fascinating insight into a neglected area of theatre history, and acknowledges Christie’s commercial success as a playwright, it largely overlooks her contribution in favour of the usual suspects: Clemence Dane, Enid Bagnold, Gertrude Jennings, Dodie Smith and others. This is a missed opportunity in an otherwise excellent book. Gale does, however, make the following interesting point: ‘Research on women playwrights, let alone performers, managers, directors and designers is, in real terms, only just beginning. It is important that we look at what was there, rather than trying to fit our findings into some preconceived notion of what it is that, for example, women should have been writing.’18

And, examining Clemence Dane’s work in Women, Theatre and Performance (2000), Gale observes that Dane ‘falls foul of many failings in theatre historiography: the unwillingness to view women’s work in the mainstream; the fear of the “conservative”; and the general lack of interest in mid-twentieth century theatre. It remains quite extraordinary that there is so little critical, biographical and historical material on a playwright so recently working in theatre, a playwright, once a household name, who has somehow been removed from fame to obscurity.’19

It could so easily be Agatha Christie to whom Gale is referring that I have gladly taken this as the starting point for my own book. ‘Suffrage theatre’ gets a great deal of attention from historians of women’s writing for the stage, but theatre written by women simply in order to entertain audiences tends to be overlooked. Gender history is a fascinating subject, but the problem with it is that it tends to be written by gender historians. Lib Taylor, in British and Irish Women Dramatists since 1958 (1993), dismisses Christie’s plays solely on the basis that she believes them to exhibit an ‘underlying collusion with patriarchy’. This view is based on a comprehensive misreading of a small number of the later works, and seems to be a common misapprehension amongst academics. And even if it were true, a playwright is surely free to ‘collude’ with whoever they like. In 1983, seven years after Christie’s death, the Conference of Women Theatre Directors and Administrators undertook a major survey of women’s role in British theatre.20 Amongst the many interesting statistics arising from this important exercise was that of the twenty-eight plays written by women produced in the previous year on the main stages of regional repertory theatres, twenty-two (or 80 per cent) were penned by Agatha Christie. More recently, on the eve of her 125th anniversary year, Christie was the only woman with a play running in the West End. It is a shame that the preconceptions and prejudices of many historians of women’s theatre appear to have dictated against a proper analysis of her achievements as a playwright.

Of the two ‘authorised’ biographies, Janet Morgan’s (1984) does its best to examine the importance of theatre in Agatha’s life and work, whilst Laura Thompson’s (2007) marginalises it in favour of an emphasis on the widely accepted thesis that much of Agatha’s work under the pen name of Mary Westmacott was semi-autobiographical. Both contain significant inaccuracies in relation to the plays, the former due mostly to the notorious difficulty of correctly dating Agatha’s correspondence (which Morgan quotes extensively) and the latter due to the author’s evident lack of interest in this area of Agatha’s work. The book you are reading is not a biography; I have had the privilege of being able to investigate in detail a particular aspect of Agatha Christie’s work, and I do not underestimate the task of attempting to chronicle the entire life of such a multi-faceted individual. So if you want to find out more about her personal life, and in particular her family history, then I recommend both of these books.

The journalist Gwen Robyns wrote an unauthorised biography, The Mystery of Agatha Christie, in 1978, based largely on interviews with people who knew and worked with Christie. Although somewhat unorthodox in its approach, it acknowledges the importance of theatre in her work, and is of particular interest in that Robyns appears to have spoken with some of the key players, including Peter Cotes, the original director of The Mousetrap, and Wallace Douglas, who as director of Witness for the Prosecution and Spider’s Web was responsible for two more of Christie’s biggest hits. Whilst inaccurate in a number of respects, Robyns’ book gives a good flavour of the spirit of Christie’s engagement with the world of theatre. As is often the case, though, her list of ‘Agatha Christie plays’ makes no distinction between those written by Christie herself and those which are the work of third-party adaptors.

It is autobiographies, rather than biographies, that provide the most fruitful source of published material for the Agatha Christie theatre researcher. In 1972, Agatha wrote the introduction to The Mousetrap Man, the autobiography of Peter Saunders, who produced all of her work in the West End between 1950 and 1962, including her biggest successes. An entertaining and opinionated romp, it gives an interesting, but nonetheless selective, insight into Agatha’s work at the height of her playwriting career, as well as Saunders’ own views on matters such as investors, critics and his fellow producers. In 1977, Agatha’s own autobiography was published posthumously. Written between 1950 and 1965, when she was aged between fifty-nine and seventy-five, it is a compelling read and gives some fascinating insights into her personality and her love of theatre, but is notoriously selective and not always entirely accurate in points of detail and chronology. Because of its focus on her early life, and the fact that her work as a playwright met with success relatively late in her career, it ironically is not the most reliable of sources on the subject. Agatha’s second husband, the archaeologist Max Mallowan, published his own autobiography, Mallowan’s Memoirs, in the same year. His opinions on his wife’s theatrical efforts are perceptive and insightful, if relatively brief.

In 1980 Hubert Gregg, who directed The Hollow, The Unexpected Guest and a couple of Christie’s later, less successful plays, published Agatha Christie and All That Mousetrap. In this bizarrely self-satisfied and resentful book from a relatively minor player in the story of Christie on stage, Gregg complains that Christie underplayed Peter Saunders’ contribution to her theatrical success in her own autobiography. What Gregg really objected to, of course, was that she had failed to mention his own modest contribution at all. I have had access to a small but very interesting privately held collection of Gregg’s rehearsal scripts and correspondence with Christie, which does not entirely bear out his version of events.

Peter Cotes, the original director of The Mousetrap, uses his 1993 autobiography, Thinking Aloud, to establish (at some length) his own position in respect of his lifelong dispute with Peter Saunders, the play’s producer. In doing so he quotes Gwen Robyns in support, although Robyns was presumably simply repeating information that Cotes had himself given to her. Saunders, Gregg and Cotes between them provide lively and often conflicting first-hand accounts of the production process of Christie’s plays from 1950 onwards, but tend to marginalise the role of Christie herself.

No Christie scholar’s bookshelf is complete without the extraordinary contribution of John Curran, whose meticulous transcriptions from and analyses of her seventy-three notebooks in his own two-volume work, Agatha Christie’s Secret Notebooks (2009) and Agatha Christie’s Murder in the Making (2011), provide a vital key to Christie’s imaginary world. Largely undated and frequently illegible, these copious, gloriously disorganised, handwritten aides memoires show work in progress as Christie developed ideas for storylines for both her novels and plays. The notebooks themselves are particularly interesting for their outlines of plays that never made it as far as a draft script, and Dr Curran has been unstintingly generous as an expert guide in this respect, sharing his knowledge in a manner that enabled me quickly to locate the particular nuggets that I was seeking. For plays that reached script stage, however, the notebooks are frequently less informative as a source for examining the work’s development than the often numerous versions of the draft scripts themselves, the typed and handwritten amendments made to them, and Christie’s sometimes extremely detailed correspondence with directors and producers as new ideas were explored and incorporated. The draft scripts for Three Blind Mice (which became The Mousetrap) and Witness for the Prosecution, for instance, are full of alterations, insertions, amendments and pencil notes made as she developed the scenarios and characters. We often see quite radical changes to plotting and outcomes taking place before us on the page. The draft scripts are, in effect, the ‘notebooks’ for the plays.

Many of these drafts are held by the Christie Archive Trust, whose collection consists mainly of papers that were removed from Christie’s cherished Devon estate Greenway when it was handed over to the National Trust in 2001, and includes a vast quantity of personal correspondence, as well as the legendary notebooks and drafts of many of the books and plays. The correspondence, mostly between Christie and her second husband Max, at times when he was either away on archaeological work or on wartime military service, gives a fascinating and deeply personal insight into Agatha’s devotion to family, the wide range of her interests and her delightful sense of humour. Almost entirely absent is any reference to her work as a novelist (which, to her, would have been the equivalent of discussing her ‘day job’). She does, however, frequently refer with obvious delight to progress on her numerous theatrical projects. The letters themselves, like the notebooks, are mostly undated (or not fully dated; we are usually told the day of the week) and often illegible; at one point even Max asks if she would mind typing her next epistle. Analysing the correspondence when a line about a play rehearsal could read either ‘it was absolutely marvellous’ or ‘I was absolutely furious’ is a labour-intensive but deeply rewarding operation. Dating the letters is an equally time-consuming process, although made easier by Max’s completely legible and meticulously dated side of the correspondence, where available. Some of the previous mistakes that have been made in documenting Christie’s theatre work have arisen from the misdating of letters, but ironically taking note of their theatrical context is often one of the most accurate ways of identifying the time of writing. When and where certain productions that she refers to were actually staged is, after all, a matter of record. Five key scripts are missing entirely from the archive: Black Coffee, Ten Little Niggers, Appointment with Death, The Hollow and Go Back for Murder; but it more than redeems itself by housing five unpublished and unperformed full-length scripts and a further seven one-act plays, all of them of considerable interest to the historian of her work as a playwright.

One of the many problems with assessing historic play texts is that what we currently accept as the published version may well contain significant changes to the draft that was accepted for production, and equally to the version that was eventually performed in front of the critics following amendments made during the rehearsal process. It is here that the Lord Chamberlain’s Plays collection at the British Library provides an invaluable resource. From 1737 until 1968 all new plays produced in the UK were subject to approval by the Lord Chamberlain’s office, thus effectively conferring a censorship role on a department of the royal household. Almost every play submitted has been retained in the collection, and scripts from the period 1824–1968 are housed at the British Library, referenced through thousands of handwritten index cards. Significantly, the script held in this collection would be exactly that performed on the first night, and thus reviewed by critics, because changes were not permitted once a licence had been issued.

Scripts had to be submitted to the Lord Chamberlain no later than a week before the first scheduled performance, and to allow for changes to be made right up to the last possible moment they were often sent at very short notice; it has to be said that the Lord Chamberlain’s office seems to have been remarkably good-natured and diligent in processing scripts and responding to them in what were frequently very short timeframes. The result of this was that playwrights effectively self-censored, as nothing could be more catastrophic than to have your play postponed by a last-minute spat with the censor when the production was paid for and in rehearsal. Each play was subject to an Official Examiner’s report on a single sheet of paper, which make for interesting reading and often show the censor in the role of would-be critic. There is also a file of correspondence between the Lord Chamberlain’s office and the producer of each production.

The card index is by play title and the handwritten, 17-volume chronological list of plays submitted for licensing between 1900 and 1968 is similarly far from user-friendly when it comes to identifying works by a particular writer; but amongst the collection’s many Christie treasures is a rare copy of the script for Chimneys, which was cancelled at the last minute in 1931, and some interesting correspondence that gives lie to the assumption that the censor never found cause to interfere with her work.

Another significant copy of any play that gets as far as production is the ‘prompt copy’ used by the stage manager to record technical cues and stage directions in rehearsal. Few of these still exist, although The Mousetrap’s is housed in the V&A Theatre Archive. The ‘acting edition’ of Christie’s plays, which was usually published by Samuel French within a year of the first performance, would often incorporate stage directions from the prompt copy which Christie herself had not actually written.

Christie researchers and biographers are also fortunate to have access to the archives of Hughes Massie Ltd, her agent, relating to her work. Edmund Cork, who took over the company from the eponymous Massie, started representing Christie in 1923 and masterminded her business affairs until his death in 1988. Central to this extensive collection are the file copies of his regular updates to Christie on the progress of her work with publishers and theatre producers. What is immediately apparent from this correspondence is that under Cork’s guidance ‘Agatha Christie’ rapidly became the first truly global, multi-media business empire based on the intellectual property of one individual. One woman with a typewriter was creating the work and one man with a typewriter (assisted by a small staff that latterly included his daughter, Pat) was responsible for selling it throughout the world; in print and on stage, as well as on film, sound recording, radio and television. Cork not only had to grapple with prototype contracts in many of the media concerned, but also with the complex and burdensome UK and international tax implications of individual worldwide royalty income on such an unprecedented scale. His unceasing labours on Christie’s behalf, and his unfaltering loyalty, charm, tact, discretion and good humour, led Christie to place a complete and deserved trust in her agent, who was four years her junior. Taking on a role which these days would be described as ‘personal manager’, he dealt with everything from organising tickets for her regular theatre visits to dealing with troublesome tenants and the purchase of a new car. So complete was the trust between them that she would give him power of attorney when she and Max were away together on archaeological digs, to avoid their work being interrupted by business matters.

Cork had an eloquent and witty turn of phrase and his correspondence, both with Christie herself and with his New York counterpart, her American agent Harold Ober, make both for an entertaining read and a comprehensive narrative of Christie’s business affairs. He may have made some mistakes, particularly when grappling with the unprecedented complexities of the network of companies and family trusts that latterly masterminded the collection and disbursement of Christie’s royalty income, but on the front line of dealing with the sale and licensing of her work he was a canny businessman and a shrewd judge of character.

The Hughes Massie archive is housed at Exeter University and contains extensive correspondence between Cork and Christie, but sadly it only commences in 1938, and is sparse before 1940, so we have to look elsewhere for information regarding the business side of Christie’s theatrical work prior to this date. Here her own correspondence with her husband can be used to fill in some of the gaps, as too can the archives of theatrical producer Basil Dean, with whom she discussed some of her work, although he never produced any of it.

Despite the huge success of adaptations of Christie’s work on both large and small screens, she herself had absolutely no interest in film or television. She disliked the majority of the film adaptations of her work that she saw and, apart from a lengthy and diligent, but unused, film adaptation of Dickens’ Bleak House, and a speculative, and equally unused, two-page film treatment for her play Spider’s Web, she never wrote for the medium. She took part in a couple of radio ‘serial’ stories on behalf of the Detection Club (of which she was appointed president in 1957) and wrote four original radio plays which were broadcast live on the BBC but, despite misinformation to the contrary, she never wrote for television. Theatre, on the other hand, was her lifelong passion, both as a creator and a consumer.

Although Cork was initially sceptical about the commercial value of Christie’s theatre projects, and was delightfully and wittily cynical about what he referred to as the ‘vicissitudes of theatre’ and the colourful personalities who populate its world, it is apparent that he quickly came to understand that the way to engage her attention was to prioritise her theatre work in his correspondence. And the result is that, doubtless against his own inclinations, a remarkably large amount of it relates to matters theatrical. As Christie herself commented in a 1951 press interview, ‘with a book you have fewer anxieties. You write it, send it to your publisher, and, after a time, it appears. In the case of a play such things as the right cast, the most suitable sort of theatre, the best time for its production, the success or not of the first night, and a dozen other things have to be taken into consideration.’21 It is evident from both her personal and her business correspondence that Christie greatly enjoyed engaging in these theatrical debates.

Eventually, though, even Cork had to admit that Christie’s work for the stage was not simply an intellectual diversion on her part but a valuable source of core income to the business empire that he masterminded. At the time when Christie’s plays were first being produced, London’s West End ‘theatreland’ as we now know it, comprising around forty high-profile commercially operated theatres, was a relatively recent phenomenon.22 A theatre building boom, facilitated by the 1843 Theatres Act’s removal of draconian licensing restrictions, had taken place between the last decades of the nineteenth century and the eve of the First World War, and playwrights now aspired to have their work presented in one of these prestigious London venues. A West End production, which would be reviewed by the national newspapers’ theatre critics and would gain considerable publicity, could greatly enhance a play’s value, making it attractive to repertory theatres, amateur groups, touring and international producers and even film companies. The key, therefore, did not necessarily lie in the success or otherwise of the first West End run but in the ability subsequently to exploit a title in these other markets. The licences issued to theatre producers by literary agents such as Hughes Massie consequently put a huge premium on achieving a West End production, rewarding producers who did so with participation in the subsidiary income thus derived and thereby ensuring that they shared an interest with the agent in achieving the maximum exploitation of a title. New York’s Broadway theatre district, which owes its current configuration to a theatrical building boom in the first three decades of the twentieth century, fulfilled a similar role to the West End in providing a valuable showcase for a playwright’s work. The licences issued to theatre producers today still reflect the importance of both West End and Broadway productions for this reason.

This book focuses on the journey that each of Agatha Christie’s plays took from page to stage in their original productions; there is simply not space to enumerate or evaluate the countless subsequent presentations of each title. Peter Haining sums it up well: ‘the number of productions of her work plus the adaptations in this country, let alone the rest of the world, has passed into the realms of the uncountable. The performances of touring companies, repertory theatres and amateur dramatic societies are simply legion … Though, like all playwrights, Agatha Christie had her flops and short runs, her name outside a theatre has long exercised a tremendous attraction for the public, and spelt gold for the management.’23

The volume and complexity of the licensing of Christie’s stage work is apparent from the enormous typewritten card index which constitutes Hughes Massie’s Agatha Christie licensing records from the 1920s to the 1990s, housed in twenty-one leather-bound volumes at Agatha Christie Limited, the company which is now responsible for the global exploitation of her work. The two files labelled ‘DD – apart from radio’ are those of the Hughes Massie Drama Department, and detail the numerous global licensing and sub-licensing transactions relating to her dramatic work (apart from radio!). In most cases amateur rights for the English speaking world were licensed to Samuel French Ltd (who also publish the ‘acting editions’ of the playscripts), and in many other overseas territories deals were done with licensing sub-agents for both professional and amateur rights. These unique records confirm once again that the plays of Agatha Christie were, and remain, a vast international industry. As soon as each West End production opened, licences were being issued from Iceland to Kenya.

Of course, commercial success is a double-edged sword when it comes to critical reputation. Christie believed that critics resented the success of The Mousetrap, the longevity of which has become something of a theatrical running joke and which is by no means her best work as a playwright; and Hubert Gregg blamed the poor critical response to Go Back for Murder in 1960 on the fact that on the same day the newspapers had announced that Christie had signed a lucrative film deal with Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer. It is undeniable, though, that the enormous and enduring popularity of Christie’s stage work in the repertory, secondary touring and amateur markets inevitably resulted in an association with cut-price and sub-standard productions, and a consequent law of diminishing returns as regards theatrical quality. Christie’s estate have become sensitive to this in recent years and have done their best to reverse the trend, with a licensing policy that prioritises quality rather than quantity.

The story of Christie’s contribution to theatre is very definitely a drama of two acts; that which predates her alliance with producer Peter Saunders in 1950 and that which follows it. Up to that date her own stage work and that of her adaptors was produced for the most part by Alec Rea and Bertie Meyer who, although great men of the theatre, failed to leave us either autobiographies or any substantial accessible business records. Until now, the Saunders archives have also been unavailable, but I am privileged to have been granted unique access to them for the purpose of researching this book. Sir Stephen Waley-Cohen, who bought Sir Peter Saunders’ business, including The Mousetrap, when Saunders retired in 1994, thereby took ownership of two metal filing cabinets in the bottom drawer of each of which are files relating to Saunders’ wide-ranging portfolio of productions and theatrical investments, including a meticulously ordered file relating to each of the nine Christie-authored plays that he produced in the West End. Here, for the first time, we see the story as it unfolded from the point of view of those responsible for the staging of Christie’s work: literary licences, theatre and artiste contracts, publicity material, budgets, accounts, and lively correspondence with directors, designers and Christie herself, including handwritten missives from her about script changes and casting, often sent from archaeological digs in the Middle East. Here we also see further confirmation of Christie’s box office success in the 1950s, in the form of statements to investors detailing the considerable profits that were being made from her work.

There can be no doubt that Saunders’ meticulous attention to detail, exemplary financial housekeeping and understanding of publicity in all its forms was instrumental in establishing Christie’s unassailable position as Queen of the West End in the 1950s. Without Saunders at the helm The Mousetrap may well not have run, and Christie would certainly never have penned her dramatic masterpiece Witness for the Prosecution. The former journalist, who was a relative newcomer to theatre when she first entrusted him with her work, became a lifelong friend and a frequent visitor to Greenway, the family home. In any event, the triumvirate of Cork, Harold Ober and Saunders proved an unstoppable force in ensuring the business success of Christie’s theatrical work. But Saunders, for all his achievements, carved his own niche in theatreland based largely on a profitable, populist repertoire rather than allying himself with the theatrical oligarchy of the day and their aspirations to educate audiences as well as to entertain.

The irony is that Christie herself didn’t need the money – her ‘day job’ took care of that – and it would have been interesting to see what history would have made of her as a playwright if she had persevered with some of her interesting early theatrical associations. The first Christie play to be produced was directed by a leading light of the Workers’ Theatre Movement, and her first West End hit was directed by the first woman to direct Shakespeare at Stratford and co-produced by a female producer and a co-operative founded by a leading Labour politician. The first ‘director’ Saunders introduced Christie to was Hubert Gregg, a comedy actor even less experienced in the role of director than Saunders himself was at the time in that of producer. The taxman might have been less happy if Christie had never met Saunders, but the chances are that theatre historians might have taken her work more seriously. And to me that is a poor reflection on theatre historians rather than on the resourceful, diligent and hard-working Saunders.

The combination of the Cork and Saunders archives furnishes a comprehensive backstage picture of the ‘Saunders years’, but although the British side of the operation prior to that is sparsely documented, the American side is not. Christie’s first Broadway venture as a playwright (a couple of third-party adaptations from her novels had preceded it) was an even bigger hit than it had been in London. The retitled Ten Little Indians was produced by the Shuberts, America’s leading theatrical producers of the day, in 1944. The company, set up by three brothers from Syracuse at the end of the nineteenth century, still flourishes; and their archive, located at the Lyceum Theatre on New York’s West 45th Street, in a splendid office complete with the brothers’ original furnishings and photographs, provides an unparalleled insight into American theatre history. As with Saunders’ archive, a wealth of original documentation has been retained, along with a well-resourced script library. It was the latter that took me to New York, on the trail of the only copies of a completely overlooked Christie script, which turned out to have been the only play of hers to receive its world premiere in America in her lifetime. Not only did I find exactly what I was looking for, but also a whole lot more …

The only other play of Christie’s to transfer to Broadway was an even bigger hit there: Witness for the Prosecution in 1954. By this time Saunders was at the helm in the UK, and he was not alone in finding the Shuberts frustrating to deal with. The more affable Gilbert Miller was therefore offered the licence to co-produce on Broadway, and while I was in New York unearthing the Christie treasures in the Shubert archive I also tracked down some of Miller’s papers, which resulted in a visit to the Library of Congress in Washington DC. Several other important theatrical archives in both the UK and the USA have assisted hugely in completing the picture of Agatha Christie, playwright from the ‘backstage’ perspective.

So, what is this book exactly? It is not a biography – if you want the story of Agatha’s childhood or her two marriages, or an analysis of how her life is reflected in some of her lesser-known works, then please look elsewhere. It is not about the ‘eleven missing days’, or ‘one missing night’, as I prefer to call it, since we know exactly where she was for the rest of the time. One of the ‘missing’ plays, I believe, may have some bearing on this over-reported episode; but you must draw your own conclusions, and my book will no doubt avoid the best-seller list by failing to come up with yet another ‘definitive’ new theory on the subject. It is not a literary analysis; there is no point at all in engaging in the long-running debate between the ‘highbrow’ and the ‘middlebrow’ when it comes to popular culture. I have neither the vocabulary nor the patience for it. Neither is it a ‘reader’s companion’. If you want to find out about the plots and the characters then I suggest you read the plays themselves or, better still, go and watch a production of them; and if you want to play ‘spot the difference’ between the novels and short stories and their adaptations then read the originals as well. This is not a book about Christie’s imaginary world, it is about the very real world of a playwright struggling to get her work produced, enduring huge disappointment and finally enjoying success on a scale that she could only have dreamt of. Because the playwright concerned happens to be female, it is unusual in not having been written by a feminist academic; as a theatre producer I have no agenda other than to set the record straight about Christie’s contribution to theatre on a number of levels. I am hoping that by offering more detail about what she achieved, particularly as an older woman in a male-dominated industry, working at a time of enormous social, political and cultural change, the value of her work for the theatre, over and above its purely monetary one, may come to be more widely acknowledged than it currently is.

To understand the unique trajectory of Christie’s playwriting career, it needs to be set within the theatrical history of the time. In Christie’s case this means charting a timeline from around 1908, when she made her first attempts at writing scripts, through to the last premiere of her work in 1972. In so doing, I will introduce a whole new cast of characters to the oft-told story of this extraordinary lady; the colourful and eccentric cast that populated Agatha Christie’s much-cherished world of theatre.

One thing that this book is definitely not about is detectives, and I am sorry if that disappoints some readers. But I have often felt like a detective myself as I have hunted down, assembled and analysed the evidence from a variety of different sources, and from often conflicting accounts of the same events. I hope that Hercule Poirot would have approved of my efforts and that what emerges is something approaching the truth behind the remarkable and previously untold story of Agatha Christie, playwright.