Читать книгу Diversify - June Sarpong - Страница 8

ОглавлениеOnly Connect

The British humanist and novelist E. M. Forster famously wrote ‘Only connect’.* And he was absolutely right. While the Earth is vast, we live in a small world full of opportunities to connect with each other, and it’s only when we do this that the walls between us come down. Yet the majority of us seem to find this incredibly difficult, caught up as we are in the things that divide us.

In one sense, of course, we are more connected than we’ve ever been before. Whether we live in the remotest parts of the world or in great international cities such as London or New York, we can connect across the globe at the click of a button. So it’s a great irony that the economic gap between those at the centre of society and those at the periphery is ever-growing. Our great cities of culture and commerce are in fact cities of strangers, where individuals have rejected relationships with neighbours in favour of superficial relationships with an online community. We often ignore passersby as we get on with our lives. We may SMH (Shake My Head) at news-feeds that show injustice at home and abroad, yet somehow we continue on, unaffected by what happens to ‘others’.

And yet, as the MP Jo Cox argued so passionately before she was murdered in 2016, we have far more in common than that which divides us. This isn’t head-in-the-clouds liberalism speaking; this is scientific fact. Genetically, human beings are 99.9 per cent identical.* Our bodies perform in the same way – we breathe the same, we eat the same, we sleep the same – and yet we choose to focus so much on the 0.1 per cent that makes us different – the 0.1 that determines external physical attributes such as hair, eye and skin colour. This focus has been the cause of so much tension and strife in the world, yet by re-evaluating the importance we place on it, we have the power to change how it affects our future. What if we celebrated that 0.1 per cent rather than feared it? What amazing things might follow for our society? The need to do this has never been so urgent – thanks to the recent political upheavals of Brexit and the election of Donald Trump, the rise of extremism and economic instability, we are now more divided than ever before – but the ability to change this is firmly within our grasp. To heal the wounds that have been exposed, we need to diversify, and we need to do it now. This is an issue I’ve felt passionate about for a long time: it informs my work, my relationships and my everyday life. And it’s more than a question of encouraging human kindness; I’ve long suspected that there is a hidden financial cost to our lack of diversity. The research that I have undertaken for this book has confirmed that.

I decided to write this book, often drawing on my own experiences, to present the issues that a lack of diversity is causing for us today, alongside the arguments for the social, moral and economic benefits of diversity. You’ll also find practical tools and ideas for how we might go about creating a new normal that is equitable, diverse and prosperous.

Why now?

On 28 August 1963, Dr Martin Luther King – for me, one of the greatest men of the twentieth century, without question – delivered his iconic ‘I Have a Dream’ speech. I have always found his words, laying out such a powerful and clear vision for global equality and unity, and delivering a message of hope that we could all be part of, absolutely mind-blowing. He presented a comprehensive vision and framework for the much-needed journey that would get us there, and I firmly believe it’s one of the best examples of the type of society we should all be striving to create. Now, over half a century later, where are we on that journey that Dr King laid out for us, and what does this mean for humanity?

The sad truth is, it’s a journey that many of us are yet to embark on. Prophesying his own assassination, King ended his last speech with ‘I may not get there [to the Promised Land] with you’, and indeed he didn’t. And there have been claims that if Dr King were still alive he would be incredibly disappointed by what he saw: a world divided by gender, nationality, class, sexual orientation, age, culture, and, of course, the two big Rs of Race and Religion.

I would argue that, actually, Dr King would not be so disappointed in what he saw, but rather in what he couldn’t see. It’s what lies beneath the surface and facade of ‘tolerance’ and political correctness that causes the real malaise – the limiting viewpoints that are hidden inside us, that we rarely speak of but often think about and, worse, sometimes act upon. Whether they are conscious or unconscious, it’s these hidden, unexamined attitudes that shape the inequality we see in society.

The evidence of that is clear in the political upheaval that has occurred in both the UK and US recently. There are many parallels between the shock results of Britain’s Brexit referendum and the Electoral College victory of Donald Trump in the US in 2016. As a board member of the official Remain campaign, I was certainly not in favour of Brexit and put all my passion and energy into trying to convince the British public that Britain was Stronger IN Europe. The result was a painful and bitter blow, and one that still hurts. We will only see the true fall-out now that Article 50 has been triggered and the negotiations have begun …

However, we are beginning to see what this new world looks like. For many, Brexit represented freedom. Yet one of the worrying repercussions of Brexit, which the experts didn’t anticipate, is the rise in hate crime and the open season on anything or anyone deemed ‘other’. Since the referendum I’ve heard phrases such as, ‘This doesn’t feel like modern Britain’, ‘A victory for xenophobia’, and ‘The revolt of the working class’. The same seems to be true of Donald Trump’s victory in the US, with David Duke, the former KKK leader, celebrating it as ‘one of the most exciting nights of my life’. I feel huge disappointment for those who wanted us to stay part of the EU, and fear what might happen to tolerance of the ‘other’ in the US – but, more importantly, I want to understand why these results went the way they did, shaking up the status quo in response to campaigns which focused on immigration and fear. The short answer is that both Brexit and Trump were symptoms of our failure to address the issues of fairness and inequality in our globalized economy.

The majority of us recognize that there are things greater than ourselves that can unite us: the world we share and our common humanity. We know that the need for understanding, connection and solidarity as one human family is more urgent now than ever. The greatest challenges of our time demand our cooperation. But how do we achieve this? When we have been separate for so long, change is not easy. But it is necessary. That’s where this book comes in.

Why me?

The daughter of Ghanaian immigrants, I was born and raised in the East End of London, home to a diverse range of people. The part of town that I grew up in, Walthamstow – or Wilcomestu, as the Anglo-Saxons called it – means ‘place of welcome’. Coincidentally, the Ghanaian greeting for hello is Awaakba, which also means ‘welcome’, so being welcoming is part of both my British and Ghanaian heritage – literally.

During my early years, Walthamstow more or less lived up to its name. We had the longest street market in Europe, where you could get anything from anywhere. The older generation of market stall-holders were mainly white working-class survivors of the Second World War. They were community-minded, and would call out to you if they knew your mum, chucking you an apple or a bag of sweets from their stall. My school was like a blue-collar version of the UN and proclaimed the belief that diversity was an asset. All the main religious holidays were celebrated – my Indian friends always brought in the best sweets on the Guru Nanak celebration. I was well liked and, being an inquisitive soul, I often found myself at my friends’ houses celebrating Shabbat, Eid and Diwali. My best friend, Levan Trong, was Chinese Vietnamese, so this meant free Mandarin lessons and amazing New Year parties.

This multicultural upbringing served as a great basis for my media career, paving the way for me to connect comfortably with people from all walks of life. After leaving school, I started an internship with Kiss FM, a vibrant, fresh radio station that looked to unite the young people of London through music. So wherever I went, it was a given for me that difference was not a problem. In fact, it was cool, and what London was all about. I carried this belief with me from radio to television, to my first presenting job. I was getting to do what I had enjoyed my entire life: meeting and talking to people from anywhere and everywhere.

In 2008 I moved to the US in the hope of finding that holy grail: the secret formula for ‘cracking America’. I wouldn’t say I ‘cracked’ America – rather, I made a small dent in her West and East Coast – but with the support and mentorship of Arianna Huffington, Donna Karan and Sarah Brown, I was able to sample a slice of the American Pie when they helped me to co-found a women’s network that was designed to facilitate this generation’s female leaders paying it forward to the next: Women: Inspiration and Enterprise (WIE) (www.wienetwork.co.uk).

I was also lucky enough to start working in American TV quite quickly, and one day, when I was filming in Las Vegas, a young sound assistant appeared on set. I noticed him straight away – and immediately felt uneasy around him. He hadn’t behaved aggressively towards me, but he was covered in tattoos. And I’m not talking David Beckham-style ink, but rather what looked like gang markings. I suspected he’d probably had a tough upbringing, possibly had a few run-ins with the law in his time. But had I really just painted this picture and gained this insight into another person’s life based on some tattoos and a bad ponytail? Yes, I had. And, regardless of the illogic of my assumptions, I began to feel intimidated.

As a woman of colour, I am all too aware of the problems that can be caused by stereotyping. In fact, being excluded as a result of being a woman, and being excluded because of your race, are two forms of discrimination I understand first-hand. So you might think that I, of all people, should know better, and should get over my discomfort and preconceived ideas and just have a conversation with this man. But in that moment I couldn’t do it. And in that moment I suddenly understood both sides of this enigma – and how our fear of the ‘other’ (whatever that ‘other’ is for you) subconsciously influences our behaviour. Whether we like it or not, ‘other-izing’ is something we all do, and ‘other-isms’ are something we all have.

I was about to quietly exclude this young man – not overtly (I’m far too polite and British for that), but subtly, which is even more soul-destroying: no eye contact and false politeness. Basically, I was prepared to pretend he wasn’t there so I could feel comfortable. But I’m happy to say that I didn’t. In that light-bulb moment, I chose to be my better self and to challenge some of my own limiting beliefs. Limiting beliefs that I didn’t even realize I had. So I went over nervously and did what usually comes very naturally to me: I spoke to him.

As it happens, he had indeed had a difficult start in life. However, he had also done a great deal of studying and self-development, and was now committed to making a better life for himself and was extremely excited about the possibility of a career as a soundman. He was brimming with enthusiasm and full of dreams – dreams that, I sensed, he secretly hoped wouldn’t be dashed by those prejudging him. Fortunately, our lead soundman had looked beyond his exterior and taken him on as an apprentice, but I couldn’t help but lament what it would take for him to rise above the limiting beliefs of others in order to achieve his full potential. He was truly a gentle soul, yet I could sense the unspoken burden he had to carry because of his appearance and the effect it had on people like me – he had to go out of his way to seem unthreatening, and to overcompensate with helpfulness.

Now, I grew up around men like this, so it was not as if I had never encountered someone like him, but I had never encountered someone like him in this context. I work in an industry that, in both its on- and off-screen talent, is not known for its diversity. I have been a very outspoken critic of this, yet I didn’t realize that I had become so accustomed to the lack of diversity at work that when the status quo was challenged, even I had to adjust.

I ended up having one of the most enlightening conversations of my life with this young man – and I realized that, had I not been able to put aside my issues around his appearance, I would have missed out on a defining moment that not only changed the way I think, but also enabled me to truly understand both sides of a problem that affects me personally. It made me wonder how many of us miss out on enriching, enlightening, even magical moments every day due to our failure to put aside our issues with external packaging.

Part of the reason so many of us are reluctant to honestly address our ism’s or voice our pain from being otherized is because it involves guilt and shame, two emotions most humans seek to avoid at all costs. Family issues that involve these emotions often go unspoken and unresolved, and the same is true for societal issues; but, as we know from our personal relationships, ignoring conflicts doesn’t dissolve them, it just allows them to fester, breed resentment and then sometimes explode. I still have a funny feeling in my stomach every time I recount this story, because to own the positive outcome, I have to accept that I went into the situation with prejudice. And this is not who I consider myself to be. But this belief is itself limited, because we are all hardwired with stereotypes – perceptions of what looks like safety and comfort, and what looks unfamiliar, something to be kept out. At times these ideas protect us, but they often trap us, too. Stereotypical assumptions on who should lead and who should follow limit potential, which in turn limits us all. Those to whom we mentally close our gates may well possess the answers to some of the greatest challenges of our age: extremism, economic instability, poverty, and the sustainability of the planet itself. To solve these complex problems (which don’t appear to be going anywhere), we need to nurture the greatest minds of our age – whatever body they reside in.

Why this book?

The aim of this book is to help people take a more positive view of others and their differences. It is not, by any means, about privileged white male bashing, but rather the opposite. My argument throughout this book is that by operating in a more inclusive way towards everyone we will be able to realize the talents and potential of everyone. Scapegoating any one group or defining an individual solely by their demographic or otherness blocks us from having the honest and open dialogue we need in order to create a fairer society. To achieve ‘business as unusual’ we have to make a compelling case that demonstrates that diversity is better for everyone, even those who will need to share a little more than they have previously, thus helping the UK and the US – two of the richest countries on the planet in terms of diversity (and in terms of monetary wealth) – to meet and overcome the challenges of the twenty-first century.

This isn’t a book that offers a whimsical argument for being nice to one another. It provides solid evidence of what’s going wrong and why, and offers practical tools and arguments for how we can change things. To use a business analogy, even the novice investor knows that the best way to achieve a return on your investment is to diversify your portfolio. If you invest all your capital in one place, you leave yourself vulnerable to fluctuations in that particular market. In the same way, companies need to ensure a diverse mix in their employee portfolio so that new ideas from people with different skill sets give them a competitive edge. Because when everybody thinks the same, we miss out on the opportunity to meet challenges with fresh ideas, we become complacent and we continue to do what we’ve always done before. The question that every company and every community has to ask is: ‘Is everyone in the room?’ And this book will try to help make sure they are.

How this book works

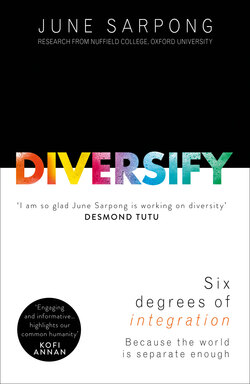

In Diversify, I will be primarily looking at the social, moral and economic benefits of diversity from a UK and US perspective, arguing that these two nations are probably best placed to lead the way on tolerance and equality. Both nations have ‘United’ in their title, both countries are born of the concept of ‘union’, and its essence is in their DNA. And both countries, as we’ve seen, are at a critical stage politically, economically, and socially.

The Others

You will notice that each section in Diversify is titled according to an ‘Other’. So what do I mean by labelling a group as ‘other’? Well, for the purpose of this book, ‘other’ refers to any demographic that is excluded socially, politically, or economically because of their difference from the dominant group(s) in society. If you are not a white, non-disabled, educated, heterosexual, middle-aged, middle- or upper-class male adhering to a version of Christianity or atheism that fits within the confines of a secular liberal democracy, then on some level you will have been made to feel like an ‘other’. The ‘others’ that I have chosen to look at here are as follows:

• The Other Man: This section looks at disenfranchised males in society: black, Muslim and white working-class men.

• The Other Woman: This section explores gender inequality in the workplace, in the media and in wider society, and what the barriers are to female empowerment.

• The Other Class: In this section I look at the class divisions that separate societies, in particular the economic gap between the elites and the working classes.

• The Other Body: This looks at what society deems as valuable bodies, and how we treat those who don’t fit the physical and mental standards of the so-called ‘able bodied’.

• The Other Sex: This section looks at how LGBTQ communities have been perceived and treated throughout the ages to the present day.

• The Other Age: This section covers ageism from the perspective of the young and the old, by analysing the disproportionate value we place on those of ‘working age’.

• The Other View: This section looks at the divisions caused by opposing political views and the vital importance of listening to the other side of the argument.

• The Other Way in Action: The final section will focus on what a fair and inclusive society might actually look like and how we might practically achieve it.*

Each chapter within these sections will feature theories, data and real-life stories that examine the perspective of each of the discriminated groups and the solutions to combat that discrimination. Each one opens with a look at The Old Way for that group – how things are and have been in the past – and closes with a vision of The Other Way – outlining how things could be. And at the end of each chapter you will also find action and discussion points to help you kick-start change in your own life, right here, right now.

The Numbers

Where diversity is concerned we have long heard the moral arguments and the rational reasons for equality, but Western society is primarily financially driven. So, to support my case further, I’ve partnered with some of the leading academic institutions and organizations in the world, including Oxford University, LSE, and Rice University TX, to provide the cold, hard numbers that demonstrate just what we stand to lose, economically as well as socially, by failing to diversify. Each of these institutions has provided some of the research and data in the book, and the Centre for Social Investigation at Nuffield College, Oxford, in particular, has provided the statistics you will see at the end of each chapter. This data is a combination of both new and existing research that delivers an overview of the challenges facing each ‘other’ group. Perhaps the most striking data in this book comes from LSE. Professor John Hills and his team at the International Inequalities Institute have calculated what must surely be the most important number of them all: the actual economic cost of discrimination – a shocking figure that brings this book to a close.

The Six Degrees of Integration

Finally, you will also find in this book what I’m calling the Six Degrees of Integration. Famously, it is said that there are just ‘six degrees of separation’ between any two individuals on the planet – from a newborn child in the most isolated tribe of the Amazon to Queen Elizabeth. The concept originates from social psychologist Stanley Milgram’s 1967 ‘small world experiment’, in which he tracked chains of acquaintances in the United States, by sending packages to 160 random people, and asking them to forward the package to someone they thought would bring the package closer to a set final individual: a stockbroker from Boston. Milgram reported that there was a median of five links in the chain (i.e. six degrees of separation) between the original sender and the destination recipient.*

But while Milgram’s experiment proves we may be linked, are we really connected? Misunderstanding and strife dominate our world and its politics, and there is now an urgent need for understanding and connection. None of us can be fulfilled in a life alone. We need others in our lives, yet many aspects of modern life are leaving us increasingly isolated. Social networking as we now experience it generally limits us to the people just one degree away, people we already know.

We need a human revolution that opens a world of possibilities for us to connect with the members of our human family who are living beyond our comfort zones and our cultures. So, in order to do this, rather than six degrees of separation, I’m introducing the Six Degrees of Integration: six steps or degree shifts in our behaviour patterns that will bring us closer to having a more diverse and integrated social circle. You will find these Six Degrees dotted throughout this book, and each one is a tool that will show you how to break free of prejudice and take action as you go on your journey towards diversity. They are:

– Challenge Your Ism

– Check Your Circle

– Connect with the Other

– Change Your Mind

– Celebrate Difference

– Champion the Cause

Human beings are notoriously creatures of habit, so change is of course difficult, but my goal in writing this book is to show how change for the willing might be made easier – and my hope is that in choosing to read this book you may indeed be one of the willing. So by undertaking the Six Degrees outlined, you will be changing your behaviour patterns bit by bit, edging ever closer to creating your own truly diverse circle. When this is true for the majority, then we will be able to change the way we think and the way we do things.

Diversify.org

Accompanying this book is www.Diversify.org – a revolutionary online space that opens up a world of possibilities for us to connect with the members of our human family who are living beyond our known horizons. www.Diversify.org is the next generation of social networking – ‘emotional networking’ – and breaks the mould as we now experience it: networking that limits us to the people one degree away that we already know. We will use the Internet in the spirit in which it was created – to connect with the lives of others, to promote our own humanity. From our own doorsteps to the most distant horizon, together we can create the unity that eludes the conventional grind of politics and diplomacy. Together we can share. Share information. Share imagination. Share vision. Share a movement that unites us, thus making it that much better and fairer for us all.

As well as being an online community, this innovative multimedia platform will also act as a resource tool for many of the elements I refer to in this book, housing content such as the ISM Calculator, case studies, interviews, videos and campaigning tips.

Remember Anansi

Changing attitudes is not easy to do, and must come from within, but we can draw on inspiration in order to empower us to do this. As a result of my Ghanaian heritage, I have always been fascinated by mythology and the power that storytelling has to shape our image of ourselves and the world around us. Ghanaian culture is steeped in folklore and myths that have been passed down from generation to generation through an oral tradition, one of the most important being the tale of Anansi – or ‘Kweku Anansi’ as he is called in Ghana – the original Spider-Man! Anansi’s story is itself a parable of self-belief and succeeding against the odds. It is a story of hope for anyone with an uphill climb to face between themselves and their dreams.

The story goes something like this: Anansi is a spider and the smallest of creatures, almost invisible to the naked eye. But he has the audacity to ask the Sky God, Nyan-Konpon, if he can buy all his stories. The Sky God is surprised to say the least. Even if Anansi could afford to buy his stories, what was a lowly spider going to do with these stories – the most valuable items in the animal kingdom?

I suppose Anansi took the view that if you don’t ask you don’t get, and what’s the worst the Sky God could do? Say no? At the bottom of the animal kingdom, ‘no’ is a word Anansi is very much accustomed to.

Still confused, the Sky God asks Anansi: ‘What makes you think you can buy them? Officials from great and powerful towns have come and they were unable to purchase them, and yet you, who are but a masterless man, you say you will be able to?’ Anansi tells the Sky God that he knows other high-ranking officials have tried to get these stories and failed, but he believes that he can. He stands firm and challenges the Sky God to name his price. Now the Sky God is intrigued, but also slightly on the back foot. When you’re a God you don’t expect to be challenged by a spider, after all. So the Sky God sets Anansi the same ‘impossible’ challenge he set the others: to bring him a python, a leopard, a fairy and a hornet. (Yes, we do have fairies in Ghana, just like everywhere else.)

Anansi is not the strongest creature on earth, but he is the most resourceful – he has to be to survive, right? Otherwise he ends up down a plughole or flattened by a newspaper. By using his wit and cunning, Anansi manages to catch all of these creatures. This involves some elaborate hoaxes and traps, but true to his word Anansi delivers to the Sky God the animals, and in return the Sky God gives Anansi the stories. Stories that Anansi goes on to share with the whole of humanity, spreading wisdom throughout the world. From that day on, Anansi grows in stature above all other creatures.

This story is dear to me because it tells us that when you have equal opportunity coupled with purpose and self-belief, anything is indeed possible. Even though the Sky God did not believe Anansi could complete the task, he gave him the opportunity anyway – the same opportunity he had given the previous, seemingly worthier, candidates, who had each failed. Fortunately, Anansi believed in himself, and with a little help from the Universe, he achieved the impossible. It’s this theory that I want to explore in more detail in this book – as well as how limiting beliefs about ourselves and each other prevent us all from achieving our full potential, and how society is robbed as a result. It’s the equivalent of mining for treasure: we are standing in a vast, mineral-rich landscape, but deciding only to dig a small section of the Earth, and so we’re missing out on all the gems the rest of the ignored land has to offer.

We have no template for a truly fair and equal society from any major civilization in recent history. In fact, we have to travel as far back as 7500BC to Çatalhöyük, a Neolithic settlement in southern Anatolia, Turkey, to see an example. Çatalhöyük is extraordinary for many reasons, not least its vast population (over 10,000 inhabitants), which makes it our first known ‘town’. However, perhaps its most notable characteristic was its inhabitants’ egalitarian ways and their lack of societal hierarchy. The town comprised an enclave of mud structures, all equal in size – there were no mansions or shacks. There was no concept of ‘rich’ or ‘poor’, no nobility or slaves, and no separate or lower castes of people. Men and women were considered equal with a balanced distribution of roles and participation in civic life.

Our so-called ‘civilized’ way of living would have us believe that a fair and inclusive society is wishful thinking – a naive or utopian idea. We are naturally programmed to follow the Darwinian theory of the survival of the fittest – a system that has only worked for a privileged few, caused social polarization and proved unsustainable. But as Çatalhöyük shows, this doesn’t have to be the conclusion. Its exact model is perhaps unrealistic in a modern capitalist society, yet we can incorporate some of the philosophies of our ancient ancestors and make our communities much more inclusive. We have the chance to change gear and move towards a more meritocratic model – a thrilling and exciting destination.

The old way isn’t working; the first country that gets this right will be a beacon to the world. The first economy that is efficient enough to capture the talents of all those available to contribute and utilize its greatest minds will produce a model that the rest of the world will be desperate to emulate.

My sincere hope is that the arguments, evidence, stories and tools in this book will help us to get there – to that Promised Land that Martin Luther King dreamed of. If we remember the story of Anansi, give each other equal opportunities, and believe in ourselves, we can achieve this seemingly impossible utopian ideal. Put simply, to make progress, we must diversify, transcend the six degrees of separation and move towards lives connected by six degrees of integration.

Because the world is separate enough.