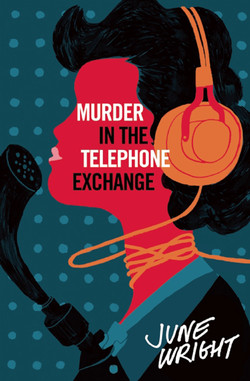

Читать книгу Murder in the Telephone Exchange - June Wright - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеPREFACE

The crime novels written by June Wright have been unjustly forgotten both in Britain, where they were published between 1948 and 1966, and in her homeland of Australia. They are distinguished by finely drawn settings in and around Melbourne, Victoria, feisty female protagonists and credible social situations, and in my opinion they thoroughly deserve a contemporary reappraisal.

She was born Dorothy June Healy on the 29th of June 1919 in Malvern, a leafy suburb southeast of Melbourne; and Catholic educated at Kildara College in Malvern and Loreto Mandeville Hall in the adjacent posh suburb of Toorak. She first showed literary promise as a schoolgirl; the respected Australian journalist P.I. O’Leary (1888-1944) awarded her a prize in a children’s writing competition run by The Advocate newspaper in Melbourne. But writing was in June’s blood; her grandfather John Healy (1852-1916) was a well-known Melbourne writer who wrote under the name “The Onlooker.” After leaving school and briefly studying commercial art, June got a job as a “hello girl” or telephonist at the Central Telephone Exchange in Melbourne (she is pictured overleaf operating a switchboard). In 1941 she married Stewart Wright, a cost accountant. They had six children: Patrick, Rosemary, Nicholas, Anthony, Brenda and Stephen.

When June’s first child Patrick was one year old, she began writing her first crime novel Murder in the Telephone Exchange (1948), which was set in her former workplace. Sarah Compton, a supervisor at the Central Telephone Exchange in Melbourne, is bashed to death with a “buttinsky,” a device used by telephone mechanics to butt in on or interrupt telephone conversations. June considered it to be “unique in the history of murder instruments. Just imagine the mess that sort of [thing] would make of anyone’s face,” she gleefully told the author of “Murder on the Brain” (1952). Maggie Byrnes, a spirited young telephonist at the exchange, who June emphatically denied was modelled on herself (I didn’t believe her!), narrates the Dorothy L. Sayers–style whodunit. (At the time, Sayers’ Gaudy Night (1935) was June’s favourite detective novel.)

June Wright in 1939: the model telephonist

While wrapping up vegetable scraps in an old newspaper, June happened to see an advertisement for an international literary competition run by the London publisher, Hutchinson. She entered Murder in the Telephone Exchange in the Detective and Thriller category of the competition, which was to be judged by Anthony Berkeley Cox (1893-1971), the author of the Roger Sheringham murder mysteries; John Creasey (1908-1973), the author of the Toff crime novels; and Dennis Wheatley (1897-1977), the author of the Gregory Sallust spy thrillers. “Unfortunately, in the Judges’ opinion, no novel was of sufficient merit to justify the award of a prize of £1,000,” Hutchinson informed June in 1945. “It has been decided, however, that certain manuscripts are deserving of publication, and to those authors who submitted entries considered to have the greatest merit we are prepared to offer an advance commensurate with the standard of the book. As your novel, Murder in the Telephone Exchange, is one of these, we have great pleasure in offering you an advance of £154 […] with an option on your next two novels.” June was thrilled.

June claimed “Murder in the Telephone Exchange was the first detective novel set in Melbourne since Fergus Hume’s (1859-1932) Mystery of the Hansom Cab published in 1886.” Whether she was correct or not, Melbourne certainly does feature a lot in her book. June saw no reason why Melbourne’s Russell Street police headquarters should not become as well known in crime fiction as Scotland Yard, she told the Australian magazine Woman’s Day; and at a swish lunch to promote Murder in the Telephone Exchange (“Oysters au Natural, Lobster Newburg, Chicken Maryland and Bombe” were on the menu), Sir Raymond Connelly, the Lord Mayor of Melbourne (1945-1948), thanked June for publicising the city in such a fashion. The setting of the murder mystery had to be “a real place, somewhere I knew and knew well, not an imaginary place,” June told me almost 60 years after her crime novel was first published.

Most book reviewers were full of praise for Murder in the Telephone Exchange, often singling out its quirky local setting, which June described in the kind of telling detail that only an insider could provide. For example, U.M.C., the author of “Have You Read These?” (1948), remarked: “Perhaps it was the Melbourne setting that gave a new freshness to the form. (One almost expected to meet the characters walking down the streets, to hear their voices over the phone.) But I think there were other factors, too: the atmosphere, the plot, the characterization, all are good.” June energetically promoted Murder at the Telephone Exchange in the press, on radio and at a number of literary events. The book was a bestseller, which according to The Advertiser newspaper in Adelaide, South Australia, “outsold even Agatha Christie [(1890-1976)] and other world-famous authors in Australia” in 1948. The ensuing royalties didn’t make June rich by any means, but she was able to buy herself a fur coat and pay for the remodelling of her kitchen.

Many people were intrigued by June’s ability to effectively juggle crime fiction writing and motherhood, which was reflected by the titles of several magazine and newspaper articles, such as “Wrote Thriller with Her Baby on Her Knee” (1948) and “Books Between Babies” (1948). June believed that housewives were extremely well qualified for writing novels, because “they are naturally practical, disciplined and used to monotony—three excellent attributes for the budding writer,” she told The Sun newspaper in Melbourne. She liked to hold up as an example Harriet Beecher Stowe (1811-1896), who wrote Uncle Tom’s Cabin (1852) when the mother of 10 children.

June’s second book, So Bad a Death (1949), which also features Maggie Byrnes, was “possibly the best Australian thriller yet written,” reported the author of “Brilliant Writer in Magazine” (1949). The book was serialised on ABC radio and also in Woman’s Day. By now, June had four children—Patrick aged seven, Rosemary aged five and the twins, Anthony and Nicholas, aged three—and two bestselling crime novels. How did she do it?

“With washing to do three days a week, I never get up later than a quarter to seven,” June told The Australian Women’s Weekly magazine in 1948. “On Monday, the biggest wash day, I rise at 5.30, light the copper, and have the washing on the line before breakfast. The twins are dressed in time for their breakfast at 7.30. Then come the other two, who have their meals with us. Monday is kitchen-cleaning day, Tuesday bedroom day. On Wednesday I scrub the back verandah and bathroom, and clean the two play rooms. On Thursday the lounge and study are done. Friday it’s back to the washtub, and the front verandah gets scrubbed. I cook an especially nice hot meal on Saturday morning, but like to sew or garden in the afternoon. Oh yes, I have to spend one night ironing, but I write on the others.”

June took up writing to make her domestic life more tolerable. “Marriage, motherhood and the suburban lifestyle were not enough—though one would never have dared to voice such sentiments then,” she confessed in 1997. By the same token, she never hid her frustration with domestic family life either. For example, at one stage, So Bad a Death was called Who Would Murder a Baby? When F.M. Doherty of Australasian Post magazine asked June why she had named it that, the then mother of four frankly declared: “Obviously you know nothing of the homicidal instincts sometimes aroused in a mother by her children. After a particularly exasperating day, it is a relief to murder a few characters in your book instead!”

Hutchinson rejected June’s next book The Law Courts Mystery. Undeterred, she tried a different genre, a psychological thriller called The Devil’s Caress (1952). According to the author of “Oven Fresh” (1952), it made her first two books “read like bedtime stories,” however it was generally not as well received as its predecessors. For her fourth crime novel Reservation for Murder (1958), June created a truly inspired character, the unassuming but strong-willed Catholic nun-detective Mother Paul, who in many respects is a female equivalent of the Catholic priest-detective, Father Brown, created by G.K. Chesterton (1874-1976). Hutchinson turned down the next book that June submitted, Duck Season Death (published for the first time by Verse Chorus Press in 2013). It seems that her publisher wanted more Mother Pauls because her final two crime novels Faculty of Murder (1961) and Make-Up for Murder (1966) both feature the inimitable nun-detective.

When June’s husband Stewart suddenly fell ill and could no longer work, she gave up writing crime fiction altogether to earn a regular salary. This was a great pity as I believe she could have written many more first-rate detective novels in the same vein as Murder in the Telephone Exchange, which not only tests the reader’s wits, but also is a wonderful evocation of post-war Melbourne. Nor had she exhausted the possibilities of Mother Paul in my view, a detective identified as “special” by a number of crime fiction reviewers. For example, according to J.C. of The Advocate (1961): “Mother Paul is indeed a most attractive personality, worthy to rank with the great sleuths of fiction, even if devoid of the eccentricities possessed by most of them. We shall be very disappointed if we do not meet her again.”

June passed away on the 4th of February 2012 aged 92. “Maybe I’ll never write a classic,” she once told Lisa Allan of The Argus newspaper in Melbourne. “Maybe that isn’t my role in life. But vegetable I’ll never be, and neither will I toss out any God-given talent simply because ‘I’m only a housewife’.”

DERHAM GROVES