Читать книгу Evening Clouds - Junzo Shono - Страница 5

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

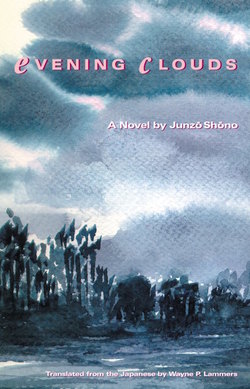

one BUSH CLOVER

Оглавление“JUST LOOK AT THE SIZE of these things!” Ōura exclaimed in surprise, standing alone in the yard.

Three vigorous clumps of bush clover grew in a neat row directly in front of the sitting-room veranda, nearly brushing the sliding glass doors. The branches of the tall one on the right stretched all the way up to within a foot of the eaves.

Approaching that part of the yard had become like suddenly wandering into a dense thicket of wild bush clover.

Since the outdoor faucet was located in back of these plants, Ōura had to push the arching branches aside and duck in behind them whenever he needed to water the shrubs in the yard. He had actually been aware of the plants’ increasing size for some time now.

“This’s getting to be a pain,” he’d been grousing to himself every time he lifted the branches out of his way.

Yet just now, on this cloudless morning near the end of August, when he emerged from his study and came up to the thriving plants, he exclaimed in amazement as though he had noticed their lusty growth for the very first time.

It appeared no one inside the house had heard his sudden outburst, though, for it provoked no response. His wife was busy rinsing out some hand wash in the bath, and the three children had withdrawn to their rooms.

“I wonder what made them shoot up like this?”

Since he could not actually expect anyone to hear his question, Ōura was merely talking to himself. He edged backward a little, then to one side as he studied the plants’ dimensions.

The plants had never reached such proportions last year. And what was more, toward the end of autumn, after the leaves had turned completely brown, Mrs. Ōura had cut the branches back almost all the way to the ground, leaving barely a stubble.

Perhaps that treatment had been good for them, however, for this year they had prospered spectacularly. Branches sprang up where none had existed before, arching tall and sweeping gently against the windowpanes in the breeze.

Of a day, if you happened to be alone in the sitting room when this happened, it could give you quite a start. The branches would move across the other side of the shoji screen like the shadow of an intruder passing by, and since that intruder looked like a veritable giant of a man (assuming, of course, that the intruder was male), young and old alike would feel their hearts skip a beat.

Perhaps the men and women of this house were simply too jumpy. Since this shadowy movement had never occurred when someone other than the family was in the sitting room alone, it was hard to know for sure. But Ōura felt quite certain that the motion would startle almost anyone—all the more if that anyone did not know about the bush clover or the way its branches stirred in the breeze.

At night, the sound of the branches brushing against the window screen produced exactly the same effect. You’d be watching baseball on TV, say, and suddenly you’d be startled by a noise and turn to look. It wasn’t as if you’d been watching the ball game with feelings of foreboding, but you couldn’t help jumping a little, wondering what might be lurking outside.

The Ōuras had transplanted the bush clover here from the nearby hillside two years ago. The plants had been puny little things then. The Ōuras’ older boy, Yasuo, had barely started fifth grade when he found them, yet none of the three plants even came up to his knees.

No one had imagined then that they would ever grow so tall.

That year, still only a year after the family had moved to their new home atop a ridge in the Tama Hills, Ōura’s foremost concern was to plant trees around the house for a windbreak as quickly as possible. Besides the bush clover, they had transplanted an occasional wild lily or oriental orchid they’d found on their mountain, but for the most part, smaller plants of that kind had had to remain a low priority.

By building their new home on the crest of a tall hill, they had gained spectacular views. But they had also placed themselves directly in the path of powerful winds. Being able to gaze out over a panorama of 360 degrees meant at the same time that their house took the full brunt of the wind no matter which way it blew—north, south, east, or west. There was simply no place to hide.

A single glance at the nearby farm houses, the oldest homes in the area, made it instantly clear what kind of place was best suited to human habitation. You could search far and wide and never find a single such house built on top of a ridge. Instead, their thatched roofs nestled placidly in the folds of the hills or among stands of trees set back from the road where they need never fear the wrath of the wind.

The builders of these farmhouses had probably selected such sites because their ancestors had been doing the same since time immemorial; they had drawn on a kind of instinctive wisdom the ancients had always possessed. Surely none of them had dithered for a second over whether to build on the summit of a hill or at its foot.

But these insights came to Ōura only after the house was completed, and after his family of five had moved in and lived there awhile. By that time, it was too late to pick up and go someplace else. They hadn’t come there on a camping trip; they couldn’t simply switch to a new spot when they discovered problems with the first site they had chosen.

Ōura felt sorely deflated to realize that he lacked the wisdom even the ancients had possessed. He knew less than the ancients had known. But it would do him no good to dwell on this humiliation. Somehow, he had to make certain that the house would not be blown away by a strong wind; he had to devise a means of self-defense.

Of course, when he said “a strong wind” here, what he actually meant was “typhoon”; he merely called it “a strong wind” to keep from picturing too vividly what could happen if a full-blown typhoon were to hit.

So long as it was only a “strong wind,” he could envision his whole house lifted intact into the sky with him and his pajama-clad family inside.

“We got blown away!” they’d cry out.

A typhoon, on the other hand, could hardly be taken so lightly.

The Ōuras had moved in April, so the season for new plantings was already well under way. If they dillydallied, it would soon be too hot. Then they’d have to wait until fall; they’d have to face the dreaded typhoon season without a single wind-absorbing tree in place.

But when a family moves to a new home in an entirely new locale, all manner of pressing needs demand attention right away. Ōura had to take care of a myriad other chores one by one before he could get to the trees.

It didn’t help that things they had all taken for granted at the old house no longer held true. And to make matters worse, their new location was not very conveniently situated. Ōura claimed it was only a twenty-minute walk from the train station, but that applied to persons with his own constitution and vigor. For Mrs. Ōura it took much longer.

“It seems like I walk forever and ever and I still don’t see the house,” was more the way she felt about it.

In fact, the very first time the two of them came to look at the lot, Ōura had marched ahead at his own pace while his wife fell farther and farther behind, until eventually they drew as far apart as the leader of a marathon and the also-rans who had given up any hope of placing.

Having built a new house on this hilltop with the intention of living here permanently and not merely camping out for a while, they now had to start from scratch to get everything put in proper order. They couldn’t simply decide to skip one thing or another because it was too much trouble. Sometimes that meant Ōura got back from a trip to the station only to have to run right back down the mountain for something else.

It really is true, Ōura concluded as he dashed up and down the mountain on these endless errands. If at all possible, a person should live his whole life in a single place, staying put in that place decade after decade and never thinking of moving anywhere else as long as he lives. That’s the ideal.

When you carry on in the same place, your efforts to make your life there as comfortable as it can be are spread out naturally over the course of many months and years. And although anything that doesn’t go according to wish really stands out, you tend not to notice all the other things that keep running along smoothly without a hitch. These other, smooth-running things didn’t get that way in a day; they grew into place slowly, the way tree roots reach around rocks that block their path or thread their way between the roots of neighboring trees to somehow find the water and nutrients needed by the branches overhead. You never realize how tightly intertwined they have become until you go to dig them up.

Moving to a new place was like having one’s entire root system ripped apart, and that was what made it so difficult.

But it did no good to fret. The Ōuras had moved here, after all, because other considerations had made it the right thing to do—and wasn’t that the same as saying the move was meant to be? In that case, instead of worrying about the old roots they had severed, they needed to concentrate on putting down strong new roots just as quickly as they possibly could.

If Ōura was in a perpetual flurry, so too were his wife and three children. Until they could establish a new set of routines for living in this unfamiliar locale, they would continue to feel pressed both in body and in spirit.

Before this, when the two older children dragged themselves from bed early because of school and sat bleary-eyed at the breakfast table sipping their miso soup, the youngest could declare it no concern of his and stay blissfully in bed. But now, with the new school year beginning this April, even Shōjirō had to get up to go to kindergarten. Gone were the days when he could stick his head out from under the blankets on a cold winter morning, remind himself that there was no rush to get up, and snuggle back into the warmth of his bed for another cozy snooze. Life did not permit him to remain a carefree child forever.

Once he started to kindergarten, grade school came next whether he liked it or not, and soon he would be longing for the good old days when he could play from morning to night at home without having to go anywhere at all.

At any event, with the entire family hurrying and scurrying about, April and May flew right by and gave way to steamy June. Not a day went by without trees for a windbreak weighing on Ōura’s mind, but the days simply outran him. After all, he also had his livelihood as a writer to make. The season for planting passed in a flash, and the new house remained surrounded by hillside as naked as the day they first moved in.

“Naked” was perhaps an overstatement. They did have some crinums, two Chinese tallow trees, and a white magnolia they’d loaded at the back of the truck and brought with them from the house that had been their home for the previous eight years.

Ōura had chosen to bring along these particular plants because they had not yet grown very big. In fact, worried as he was that their household goods might not all fit into the truck, he had at first hesitated to dig up even these relatively small plants.

The persimmon and peach trees he had planted at the old house both produced wonderfully sweet fruit, but he reluctantly left them behind.

“It’d be too much trouble to try to take these, too,” he had had to concede.

He left in place, as well, a lilac bush that his older brother bought and planted for them as a housewarming gift the first time he came to visit from Osaka. Their old yard had had many other trees and shrubs as well, but the persimmon and peach and lilac came to mind first because those were the ones Ōura missed most.

“We should have at least brought those along,” he had kicked himself over and over in regret.

Unfortunately, the crinums and tallow trees and magnolia that had made it onto the truck with their belongings failed to thrive after being transplanted. They had difficulty getting established because they were always being buffeted by the wind (that was Ōura’s reasoning at the time, anyway). The two tallow trees gradually withered over the course of the spring and died at the beginning of summer; the magnolia put out a few leaves but then seemed to have stopped growing as it jostled constantly in the wind.

This is not looking good, Ōura thought.

All this time he had still been trying to decide what to do about trees for a windbreak. Most of the old farmhouses in the area seemed to be surrounded by live oaks, so perhaps that was what he should choose. But mightn’t chinquapins be better? Or was there yet another species he should consider—a tree that was particularly sturdy and quick to grow?

Not a day went by without Ōura pondering these questions. Yet now the tallow trees had died, and the magnolia looked touch-and-go as well.

Their hilltop location certainly got more than enough sunshine. Stands of cedar and pine grew only a short distance away. Some of the larger red pines looked like they must be a hundred years old. And there were some sawtooth oaks as well. Since all these trees grew on the same mountain, it could hardly be the fault of poor soil. It had to be the wind.

In the morning, Ōura would note happily that the day was calm, but then a wind would rise in the afternoon. The entire Tokyo area was notoriously windy in the spring. Gusting winds could throw up clouds of dust thick enough to obscure the sky. Even with the storm shutters closed tight, dust filtered into the house and settled everywhere. Ōura had grown quite accustomed to this at their former home.

But the winds there had never been so utterly relentless, day after day, the way they were here. On their new mountaintop it was as if a high-wind advisory needed to remain permanently in effect. Once, when Ōura stepped outside, a powerful gust took hold of the front door and slammed it against the wall so hard it wrenched it out of shape. That was the kind of wind they had to contend with.

Ōura wondered if other areas around Tokyo might also be experiencing unusually high winds, but nowhere in the paper did he find any such reports. No storefront signboards had blown off or hit unfortunate passersby in the head.

When the dry cleaner or the butcher’s apprentice came by with their deliveries, they gave no sign that anything was out of the ordinary, so even right here in their own little town it apparently wasn’t particularly windy in the business district down by the train station.

At this rate, regardless of what kind of tree Ōura chose, before he could plant trees to make a windbreak for the house, he’d need to make a windbreak for the windbreak. Otherwise, the trees might never be able to establish themselves; the constant jostling of the wind would keep the new roots from ever being able to grab hold of the soil.

Perhaps a spell of several quiet days in a row would let a few new roots begin to take hold, but then as soon as the wind came up again the thin strands would get torn right off. With this cycle repeating itself over and over, soon even the most determined tree would have to give up.

But who had ever heard of planting trees to make a windbreak for the trees you wanted to plant for a windbreak? Ōura would simply have to do what he could to help the first trees he planted take root. He could secure the trees firmly in place by tying bamboo poles sideways across the row of trunks, or he could prop up each of the trees separately with its own set of supports. Even on the flat lowlands, people had been using such methods for centuries in order to help their trees grow healthy and strong.

Before Ōura had planted a single tree to tame the wind, as he was still fretting about what exactly he should do, he received a special-delivery letter from his brother in Osaka one day:

“I had meant to send you something to celebrate your move long before this, but the days just kept slipping by. Today I finally got out to the rose gardens at Hirakata and arranged to have five kinds of bush roses and five kinds of climbing roses shipped to you. You should get them in no more than a week, so you need to start the following preparations as soon as you receive this letter.

“First, choose a well-ventilated spot with plenty of sunshine and dig holes one meter across by fifty centimeters or more deep (the deeper the better), at least one meter apart for the bush roses and two meters apart for the climbing kind.

“Next, fill the holes to half their depth with a well-blended mixture of oil cake or chicken manure and humus from under the fallen leaves in the woods. But make sure the roots of the roses won’t actually come in contact with these soil amendments when you plant them.”

Off to one side Ōura’s brother had sketched a simple diagram illustrating the dimensions.

As soon as he finished reading the letter, Ōura went to get his shovel and headed for the yard. If he didn’t get to work right away, the holes might not be ready by the time the roses arrived.

In recent weeks, Ōura had been thinking only of planting a windbreak. His mind was filled with pictures of trees that would grow rapidly to maturity and hide the entire house from view. Putting in roses could hardly have been farther from his thoughts, for his heart was consumed by something quite removed from ornamental interests.

His brother, however, knew nothing about any of that. When they moved into their previous home, he had bought them a lilac bush; this time he was sending roses. This brother was fond enough of trees, too, but his real love was for flowering shrubs. Ōura, for his part, wasn’t obsessed with trees because he particularly preferred them, either. It was just that he had been forced by circumstances—lest a violent gust blow his family, house and all, into the sky—to focus his attention on trees that could protect them from the wind.

Only a few days before this, Ōura had written his brother to tell him how some mutual friends of theirs had come to visit, each bringing a gift from his yard—a pepper tree, a spiderwort, a shoot from a redbud paulownia, and a hydrangea. In his letter he had given an account of the rollicking party they had had, too, but he hadn’t mentioned the winds that visited them so mercilessly, day after day. He could easily have added a note about the winds, but he hadn’t.

Under the circumstances, his brother could not know that what Ōura really wanted was trees to protect the house. It would be tempting fate to let unappreciative thoughts enter his mind—such as to wish his brother had not sent the roses.

Ōura set briskly to work digging the holes. If he allowed as much room as his brother had stipulated, the whole house would be surrounded by holes, so he decided to reduce the measurements a little. It took him two days to finish his excavations.

“I feel like a grave digger,” he mumbled as he scooped out another shovelful of dirt.

Digging the holes did not complete the required preparations, however. Next he had to round up the soil amendments his brother had named. Having expended all that effort removing the dirt from the holes, he now had to fill them halfway full again with something else.

Down by the station was a rice store, which the owner ran with the help of his eldest son. The way the owner’s T-shirted stomach bulged out over his tightly wrapped apron reminded Ōura of the potbellied little toddlers he often saw running around looking so cute. He was a gentle, easygoing man—no doubt made that way by growing up at the foot of these verdant Tama Hills, soaking up the ample sunshine, drinking the sweet water, and enjoying to his heart’s content the plentiful harvests of persimmons and peaches and pears the region offered.

“Would you happen to know where I could buy some oil cake or chicken manure?” Ōura inquired.

“They sell oil cake at the farm co-op, but they might not be able to help you if you’re looking to buy just a little.”

“I need it for planting some roses. For fertilizer.”

“In that case, chicken manure should do fine.”

“Is there some place that sells it?”

“It wouldn’t be for sale, but every farm around here has chickens, and I’m sure they’d be happy to let you have some if you asked. They’re rolling in the stuff, so they’ll tell you to help yourself to however much you want.”

He looked ready to burst out laughing.

“We don’t really know any of the farmers yet, so I’m not sure I feel comfortable asking them for favors. Would there be anything else that might work instead of oil cake or chicken manure?”

“You mean something we might have here?”

“Yes.”

“Well, we have fishmeal. I suppose that should work.”

He went to get something in a paper bag and poured a little out onto his palm for Ōura to see.

“What exactly is it?”

“Dried sardines.”

“The innards?”

“No, not just the innards. They press the oil out and then dry what’s left. It’s for chicken feed, and there’s some problem with the oil so they have to get rid of it first.”

“They feed it to chickens?”

“Uh-huh. Everybody uses it. All the places that have chickens.”

“I wonder if it’ll work for roses.”

“I’ve never tried it myself, but it seems like it should be okay. If chicken manure works, then the fishmeal the chickens eat ought to do the job, too, I’d think.”

“I suppose that goes to reason.”

They both laughed.

Just to be sure, the rice man phoned a farmer he knew who cultivated roses (as he spoke on the phone he still looked about to burst out laughing). The farmer said it should work fine, so Ōura went home lugging two large bags of fishmeal under his arms.

The Ōuras had a slim notebook labeled “Planting Log” on the cover.

Yasuo had charge of it, and each time they planted something new in the yard, he recorded the date, the name of the plant, the number planted, and the place of purchase or the place it was transplanted from.

They had not actually started keeping this log right away; they had begun it in October of the year following their move. For all the things they had planted before that, they had had to reconstruct an approximate record from memory.

The advent of the Planting Log a year and a half after their move signified that Ōura’s preoccupation with trees for a windbreak had finally come to an end. Until then, the need to do something about protection from the wind had continued to occupy his mind, but at around that time he had finally been able to breathe a little sigh of relief. A glance at the entries for that October help confirm this:

Camellia 2 From Ozawa’s

Persimmon 1 From Ozawa’s

Maple 1 From Ozawa’s

Ozawa was the name of a gardener Ōura had gotten to know that spring. Like the rice merchant, he was a man who had lived here at the foot of the Tama Hills all his life, and he had the same easygoing manner. For the moment, he need not be introduced further.

Camellias and persimmons and maples can all reach a considerable size if permitted to grow, so these plantings could certainly have been part of a windbreak. But Ōura had chosen the persimmon tree in anticipation of the sweet fruit it would produce, as a replacement for the bountiful tree that the entire family so regretted leaving behind at the old house. Ever since their move, they had all shared the wish to someday have a persimmon tree in their yard again.

The camellias and maple were selected for their ornamental appeal. They stood as the clearest evidence that Ōura had emerged from his stubborn and single-minded obsession with trees that could fend off the blustering wind, and that his heart finally had room for aesthetic sensibilities to assert themselves once again.

This did not mean that he believed planting twelve chinquapins (after endlessly vacillating between live oaks and chinquapins, he had ultimately settled on the latter) and three Himalayan cedars around the house immediately gave them all the protection they needed. Perhaps in five years or so the trees would grow to a reasonably reassuring size, but there was no guarantee that a typhoon would not strike in the meantime. And nobody could tell beforehand what might happen if a typhoon did come their way.

Bush clover 3 From the mountainside

Of the plants thus recorded in Yasuo’s handwriting, the cluster on the far left was now in full bloom. Coming up close, Ōura could see several bees busily dodging in and out among the branches.

So they get nectar from bush clover, too, he thought as he watched them buzzing about.