Читать книгу The Impossible Five - Justin Fox - Страница 5

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

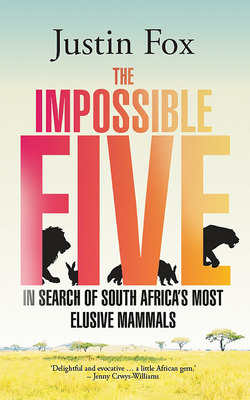

NOT THE BIG FIVE

ОглавлениеLike most South African children, I grew up with stories of animals. Fairy-tale animals, dream animals, intelligent domestic animals and dangerous, toothy, wild animals. Members of my family took turns reading me to sleep at night. There were the Barbar the Elephant books and Dr Seuss’s Cat in the Hat tales, Richard Scarry’s heroic characters epitomised by the intrepid Lowly Worm, Beatrix Potter’s world of erudite rabbits, books of African folktales and Kipling’s Animal Stories.

Winnie the Pooh and his coterie were favourite bedtime companions, and today I’m still able to recite whole chunks of A. A. Milne. Who can forget Piglet meeting a Heffalump, Eeyore losing his tail or Pooh getting his head stuck in a honey jar? These are indelible moments in my literary upbringing. I remember odd but important details, like the fact that Tigger had trouble climbing down from trees because his tail kept getting in the way. For years, I wondered if real tigers experienced the same difficulty.

Perhaps the book that most captured my imagination was Alice in Wonderland. The story of her adventures down the rabbit hole seemed to my young mind completely believable. Lewis Carroll’s characters – the March Hare, Cheshire Cat and White Rabbit – inhabited my suburban playground as much as they did that enchanted college garden in Oxford, the setting for his famous book, written in the 1860s. Wonderland could be discovered anywhere.

When I was old enough to read for myself, more weighty tomes such as Watership Down, Jock of the Bushveld and Gerald Durrell’s animal escapades took over. I began reading African tales of myth and legend, which often masqueraded as fact. I was never exactly sure whether the white lions, giant snakes and talking apes I read about were fictional characters or adaptions of flesh-and-blood animals. Real creatures and imaginary ones morphed into one. It was probably impossible to meet a real Pooh bear, but probably just as impossible to meet an aardvark. Or was it?

Growing up in the city, my contact with animals was mostly domestic. We had two dogs and a cat, as well as a parade of smaller fry that passed through the house, or hid in the attic, or flew away, or floated belly-up in a bowl. I loved my cat best of all, and as Ling was an intelligent and indulgent Burmese of impeccable breeding, he played games with me every day after school and slept on my bed each night.

I realise now that my affection for Ling led me to an understanding, a love even, of his movements and moods, the way he purred, or stretched after a snooze, or stalked a bird with his slow-motion gait. Human children are, in a way, imprinted by their pets. That languid, cat-walk stride, that bored, eyes-half-closed, don’t-bother-me-I’m-thinking-about-Nietzsche look – I grew to know such things intimately. And so it was that when I eventually met bigger cats in the wild, there was an immediate, electric recognition. The love was already there.

When I was old enough for malaria tablets and able to sit still for longish periods without making a fuss, my parents started taking winter holidays in game reserves, in particular the Kruger National Park. The excitement was almost unbearable. This was a real-life, adult Wonderland, just as alluring as Alice’s. A hundred kilometres before arriving, I’d already have unpacked the binoculars, Roberts bird book and foolscap pad with three columns marked mammals, birds, reptiles.

The challenge was always to find the Big Five. On most Kruger holidays, we managed the first four: elephant, rhino, buffalo and lion. It was always the leopard that eluded us.

After countless unsuccessful attempts, finding the spotted cat became something of an obsession for me. It was not until adulthood that I saw my first wild leopard, draped on the branch of a leadwood tree beside the Sabie River, looking just as I’d always expected him to look. There was a jolt of recognition … and elation. It felt like a kind of benediction. Ling had long since passed into the forests of the night sky by then, but I knew the set of those limbs, those steady golden eyes, the sinuous beauty as though they belonged to a long-lost friend.

As an adult, I continued the childhood tradition of visiting game parks each winter. My taste had broadened, and I now sought rarer animals: little-brown-job birds, strange insects and shy night creatures such as bush babies, civets and genets.

Over the years, my list of new creatures to find grew longer. There was one particular animal that replaced leopards on my most-wanted list: the pangolin. I’d heard a lot about these armadillo-like, prehistoric-looking mammals, and wanted to see one for myself. Each time I visited a game reserve, I’d ask the rangers about pangolins. Invariably they’d shake their heads and tell me to give up. ‘Impossible,’ they’d say. Most rangers had never seen one themselves, even those who’d spent a lifetime in the bush.

My fruitless search for pangolins got me thinking about creating a list of the mammals I’d tried and failed to find over the years; those animals you had just about zero chance of seeing. Instead of the Big Five, I would try to find the Impossible Five. After much deliberation, I narrowed my search down to a shortlist that included such animals as the black-footed cat, Cape fox, aardwolf and Knysna elephant. The last on this list was discounted after I found out there were probably less than five left in the Garden Route forests, my chances of finding them were nil, and these elephants were not a subspecies or genetic variant, but simply common-or-garden Loxodonta that enjoyed a bit more leaf cover than their cousins.

I also considered a number of smaller, critically endangered African mammals, including four species of moles and two bat species. However, my final five were all distinctive, sexy mammals that had long frustrated me (and my friends, family and many rangers I had spoken to). My Impossible Five would be: Cape mountain leopard, aardvark, pangolin, riverine rabbit and (naturally occurring) white lion.

These animals had survived into our modern age largely due to their elusiveness. Their ‘impossibility’ was their tenuous insurance against extinction. They were still wild and free, most of them living outside national parks, still occupying the same territories they had for millennia. As such, they were symbols of wilderness – that wildness once everywhere, and which is now drastically curtailed and shrinking by the day.

Their continued presence, even if never seen, was a comfort, a kind of ecological money in the bank. If they disappeared or were driven into contained environments, our human species would be far poorer for it. I began to think of my creatures’ impossibility as their saving grace – our saving grace. In this light, it didn’t matter if I found none of them, and my mission was a complete failure. As long as I knew – we knew – they were still out there, that would be enough.

My quest, or series of journeys, was going to be a costly business. So I approached a few magazines and websites, as well as a vehicle manufacturer (Land Rover) and various safari lodges, to help with logistics. In return, they’d get coverage in the print media and online, and there was also the dangled carrot of a probable book with the catchy title The Impossible Five. I set aside six months to find my animals: one a month each, with a month to spare. In the end, it took me nearly three years.

Before setting off on my first journey, I took a closer peek at each of my five contenders. The Cape leopard is smaller and more elusive than its larger cousins elsewhere in Africa, and far rarer. Its territory is the mountain ranges around my home town, but it is hardly ever seen, and precious little is known about the last remaining big cats living so close to Cape Town. In a sense, these mysterious creatures have become an emblem of the old Cape – a Garden of Eden thronging with big game before European settlers arrived.

They are also a reminder of our very distant past, when we were ape creatures and nights were ruled by the spotted cat that hunted us in the dark. This notion led Bruce Chatwin to ask in The Songlines whether Dinofelis, the ancestral leopard, ‘was a specialist predator on the primates? … Could it be … that Dinofelis was Our Beast? A Beast set aside from all the other Avatars of Hell? The Arch-Enemy who stalked us, stealthily and cunningly, wherever we went? But whom, in the end, we got the better of.’ Perhaps in our subconscious, we humans still recognise who is really the Prince of Darkness, the prince of our darkness.

Aardvarks and pangolins are not as rare as Cape leopards, but just as hard to find. The aardvark is an improbable, but adorable creature with bunny ears and a Hoover snout. It looks as though evolution should have knocked it off the branch long ago. But somehow it persists, largely due to its elusiveness and nocturnal habits. The pangolin, with its prehistoric armoured scales and shambling gait, occupies a similar terrain, and has nocturnal habits and an insectivorous diet similar to the aardvark. My best chance of finding these two creatures was by making a trip to the Kalahari Desert.

Lions are kings of the bushveld, members of the Big Five, and should have no place on an impossible list such as this. However, white lions are a different story altogether. At the time I began my research, it was thought that there were only a handful of naturally occurring white lions in the wild, and these could be found in the Timbavati region of South Africa’s Limpopo Province. But these cats moved through vast territories, so I was going to have to be on standby for months, ready to hop on a plane and follow up one of the rare sightings.

The riverine rabbit is officially the most endangered mammal in Africa, and the thirteenth most endangered on Earth. This little creature was probably going to be my hardest nut to crack. To make matters worse, there appeared to be precious little information about it. I tried to do some background reading, but soon gave up. My fauna bible, Southern Africa’s Mammals by Robin Frandsen, was disconcertingly scant on detail: ‘Little known, solitary rabbit … Gestation period: unknown. Mass: unknown. Life expectancy: unknown. Spoor: unknown. Length: 43 cm.’ That’s an awful lot of unknowns. At least I knew precisely the length of the creature I’d be looking for on the interminable nights that lay ahead, driving the dirt tracks of the Little Karoo in search of a nondescript bunny.

I opened my journal and wrote: ‘Riverine rabbit: 43 cm.’ Then I closed the book. It was time to pack the car and take to the road on a magical quest of miracle and wonder to find the Impossible Five.