Читать книгу Tango - Justin Vivian Bond - Страница 6

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление2

Once I had my prescription I began to reevaluate my past through the lens of this recent discovery. I started remembering what life had been like for me when I was a child. For the first three years of elementary school my desk was always separate from the rest of the class. There were twenty-five students and the teacher, and I was by myself off to the left. I thought this was normal. I wasn’t hyperactive or difficult; I think I was just extremely aware of everything going on around me and it was difficult for me to choose which thing to concentrate on the most.

I told my mother of my diagnosis. She seemed surprised and didn’t remember the many times she had come in to school on Parents’ Day and wondered why I was seated separate from the class. But mothers remember what they want.

A few days later when I was on the phone with my sister Carol, she told me she’d had a conversation with our mom about my ADD. Then she said to me, “Don’t you think you were seated separate from the rest of the class because you were always trying to be the center of attention?”

This made me feel like my brain was splitting open. When asked these kinds of loaded questions by my family members, I immediately go on the defensive. I was hurt at the insensitivity of what seemed like her invalidation of what I was telling her, as if my issues were “all in my head.” So many things that I felt, thought, or experienced as a child were attributed by my family to being all in my head. When they said something hurtful and I got upset, it was all in my head. When I felt like someone was making fun of me, it was all in my head. If my mother criticized me and I reacted negatively or defensively, I was too sensitive. If I was nervous or upset about something like a performance or show I was about to do, my father would say to me, “Why are you nervous? You have no reason to be nervous.”

For a huge portion of my life one of my greatest challenges has been to flatline myself emotionally around my family, because when I expressed my feelings I was told that I was either overreacting or being hysterical. Maybe this was because I bottled so much up that when feelings finally did come through it was in the form of an explosion. Nevertheless, my sister Carol and my mother believed that I was always trying to be the center of attention, and this simply wasn’t true.

“No, actually, I think I was made uncomfortable by the fact that I received too much attention.” My sister didn’t seem to believe me.

“It’s okay to want a lot of attention. I did. Everyone wants a lot of attention.”

“Maybe you wanted a lot of attention. Perhaps that’s why you were the president of your class from sixth grade till the end of high school and were voted most popular in your class. I don’t think I would have spent most of my teenage years hiding out in my best girlfriend’s room reading gothic romance novels and listening to Elton John records if I wanted so much attention.”

THE FIRST TIME I WAS SEPARATED FROM THE class was in first grade. I think I felt very lonely then because I wasn’t sure exactly where I fit in. Generally, I found myself befriending the less outgoing, shy people in the class. I was very good at bringing them out of their shells and making them laugh. I was attracted to outsiders. I always felt very skittish when surrounded by too many people—when I felt like I had too many eyes upon me.

I have a cousin Pam who’s three months younger than I and who I always felt extremely close to. When I wasn’t with her I imagined she was with me, and I took great comfort in her presence. I distinctly recall arranging it so that I had to sit at the end of the row of desks in order that there would be room for a desk for my invisible cousin to sit next to me. There was an imaginary desk for an imaginary friend in an open space, which made me feel safe. I quickly learned that if I got stuck between two people all I had to do was engage them in too much conversation and my desk would be moved. I would be seated on my own and have a space to create a world around me where I felt safe, in spite of the fact that I had a “behavioral problem.” When on my own I was perfectly fine. When left to myself without the distractions of so many people around me I was much better able to focus on the tasks at hand. I realize now that my “need for attention” was really more of a need for simplicity.

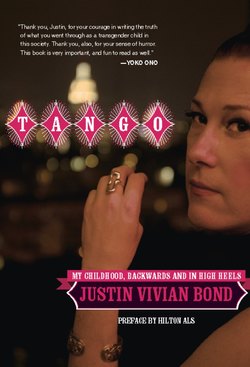

I STARTED ELEMENTARY SCHOOL IN 1969. AT THAT time, people weren’t diagnosing children with mental health issues the way that they do today. We were just “trouble.” I mention this because Carol, during the same recent conversation, told me a story about a boy who grew up next door to us who had been my archnemesis and who had recently been arrested for impersonating a drug enforcement agent out on Route 81. Evidently they had nabbed him somewhere between the Valley Mall and Martinsburg, West Virginia. According to my sister he had been operating under an assumed code name: Tango.

“Did you hear about Michael Hunter?”

Immediately I felt a fluttering in my stomach. I hadn’t seen Michael Hunter anywhere other than in my dreams for a good long time. In spite of the fact that I hated him, we had been lovers, if you could call it that, from the ages of eleven to sixteen. My sister knew there had been a lot of tension between us when we were kids, but I don’t know if she really knew the full extent of our relationship. Nonetheless we got a good laugh that he had given himself the code name “Tango,” and wondered if it came from the 1980s Kurt Russell movie Tango and Cash in which Kurt Russell plays a narcotics detective who is paired up with a partner he can’t stand but with whom he has to work in order to clear his name. Clearly, Michael Hunter was living a life of delusion and may have had some kind of psychotic break.

It is a terrible thing to laugh at another’s misfortunes, but Carol and I couldn’t help but laugh at the absurdities of Michael Hunter’s arrest that day. As soon as I got off the phone, I went online and found a newspaper article about his arrest with the headline “Man Posing as Cop Nabbed,” along with his mug shot. His face looked tragic. He had become a middle-aged bald man. Instead of feeling any kind of satisfaction I felt tremendous sadness because I knew that he had been through hell. I did think, however, that calling himself Tango showed that somewhere inside he still had a touch of panache. I thought of Kurt Russell who had gone from playing a boy who could make himself invisible in Disney’s Now You See Him, Now You Don’t to being a gun-toting action adventure hero in such films as Escape from New York and Death Proof. The newspaper said that Tango was wearing a bulletproof vest, fatigues, and a green shirt that read JOINT TERRORIST TASK FORCE when he was arrested. He probably thought he was starring in Death Proof 2: The Sequel.

It was reported that the police had found handcuffs, two-way radios, and various law enforcement equipment in Michael’s blue BMW. Reading this, many memories came flooding back. This definitely wasn’t the first time “Tango” had impersonated a law officer. Tango and I had a history of arrest ourselves. When we were young, one of the games we liked to play involved one of us posing as an undercover police officer and the other as a criminal. Many summer afternoons were spent getting frisked in his parents’ two-car garage, where invariably one of us was found with a concealed weapon in his pants.

It was all too much. After reading the article I called my sister back. Carol is now an elementary school vice principal who deals with lots of medicated children. Looking back, we both agreed that Michael had probably had mental health issues since childhood.

“YOU WALK LIKE A GIRL.”

“No, I don’t.”

“Yes, you do. You walk like a girl.”

“Well, I’m a boy, and this is how I walk. So I don’t walk like a girl, I walk like a boy.”

I had this conversation with a little girl when I was nine years old, in the fourth grade. I remember the spot where it happened. It was in the doorway at Pangborn Boulevard Elementary School as we were exiting onto the playground. She didn’t say it to be rude. It was just an observation. For me, it was more complex. I was simultaneously flattered and confused. I hadn’t been aware that I walked like a girl. I don’t even know that I aspired to walk like a girl. But I’m sure I never tried to walk like a boy. I didn’t like boys. I’d never really liked boys.

FOR THE FIRST PART OF MY LIFE, I THINK MY role was very clearly defined: I was my mother’s most glamorous accessory. I was cute, fairly at ease socially, and I began talking at a very young age. My parents were delighted that their first child was a boy and it was several more years until my sister came along, so I was the focus of quite a lot of attention.

I was mostly surrounded by women and girls. My mother’s best friend, who I called Aunt Judy, had a daughter who was one year older than me. I had a girl cousin who was three months younger than me and a slew of female teenage cousins who were always dropping by, especially when they needed to use our bathroom as they were headed from their house in the country to go shopping downtown.

I was raised by girls and I liked it. I was like a pet monkey that they would tease and dress up and play with. This seemed perfectly normal to me and I remember enjoying it. Once I entered school in the autumn of 1969, I was thrown into social situations with boys for the first time. I was appalled. They were always racing around, screaming loudly, playing with trucks, throwing balls, wrestling, and sweating. I found it disgusting and unnerving. I wasn’t used to so much aggression and commotion. I preferred skipping rope and playing house to running around. I enjoyed climbing the jungle gym with the girls. My teachers’ reports were always the same: “He is very alert, a good student, but needs to learn how to play with the other boys.”

By the time fourth grade rolled around, I had become fairly comfortable with most of the boys in my class simply because I was familiar with them, as it was a small school. Nonetheless, I didn’t play or socialize with them. I’d had several girlfriends, and as a matter of fact I had “married” Patty Chase in second grade. Her sister performed the ceremony in her parents’ house, and I was devastated when I was told we weren’t going to be allowed to live together. Obviously, when no one took our marriage seriously, I became disillusioned. Well, they had their chance . . . Anyway, I had several girlfriends in the fourth grade, including Kim Bell who wore white go-go boots to school. I was very happy because I got to sit next to her and stroke her go-go boots, which to me had the texture of marshmallow fluff, one of my favorite treats. Kim didn’t seem to mind me stroking her go-go boots one bit, and my teacher didn’t stop me because I think she was relieved that I was showing interest in a girl instead of trying to be one.

IN 1964, MY PARENTS BOUGHT A THREE-BEDROOM ranch house in a development at the edge of town. Our street was paved, but the rest of the freshly plowed area consisted of red clay. The Kendalls, our neighbors to the rear, had a son named Greg who was a bit younger than me, and I quickly became friends with him. In their front yard they had a great big boulder that we used to play on, until someone fell and scraped their knee and the boulder had to be removed. That’s how it was then. They tried to keep us from climbing trees in case we fell out. They removed boulders so no one would skin their knees. I’m surprised they didn’t put cotton bunting on the sidewalk in case someone fell. It was all about the safety of the children.

Next to the Kendalls, a new house was being built. Eventually, a couple moved in with their daughter, Eva. They had an aboveground pool, which was very exotic, and they were almost, but not quite, hippies. The Brinings were young and cool and much hipper than anyone else in the neighborhood. Eva became one of our best friends. Greg, Eva, and I played together every day. But one day when we knocked on her door, her father said that Eva wasn’t living there anymore. Our parents told us that she wouldn’t be coming back because her parents were getting a divorce. This was the first time anyone we knew had parents who got divorced, and it was sad for us because our friend just disappeared.

THE BRININGS’ HOUSE WAS SOLD TO AN AFRICAN American man named Mr. White. Mr. White was a bachelor and the first African American man to move into our neighborhood. We were very excited and wanted to welcome our new neighbor. We didn’t know how to make a pie and our mothers were busy so we decided that since we had just gotten a new set of crayons, and since he was a “colored” man, Greg and I would write him a poem using all of our new colors: Red is nice, we like red. Green is nice, we like green . . . making our way through all of the colors . . . we like purple, blue . . . we LOVE White! Then we got to black. Black is ugly, we hate black.

Very excited and proud of our poem, we knocked on Mr. White’s door, smiling from ear to ear, and handed it to him. We said, “Welcome to our neighborhood, Mr. White!” He looked at the card. We were sure he would be delighted by our neighborliness but instead he looked very shocked and asked, “Do your parents know you wrote this?”

“No. We did it on our own, Mr. White. We would have baked a pie but we don’t know how.”

He didn’t seem at all pleased with our gift, which was very confusing to us. We went home and told our parents Mr. White wasn’t very friendly. Soon, they received a phone call from Mr. White and we got into big trouble. We hadn’t realized Mr. White was black, we thought he was colored, which is why we wrote him a poem about all the colors we liked. Most kids prefer red or green to black, but we didn’t realize that saying we hated black would be an insult to Mr. White. Our parents brought us over to his house and, in tears, we apologized. “We’re so sorry Mr. White. We didn’t know you were black.”

He was very nice to us from then on, although he moved out a few years later. In all honesty we were glad he moved out because we wanted someone fun like Eva to move back in there. And Mr. White didn’t let us swim in his pool.

FINALLY, A NEW FAMILY MOVED IN. THE HUNTERS. They had two boys, one of whom was my age, named Michael, and his older brother, named Bobby. On Michael’s first day of school I discovered he was in my class at Pangborn and our teacher Mrs. Schmid, clearly with an agenda, decided I should show Michael around since he was my new neighbor. I was very interested in knowing what Michael was like but I was also suspicious of the motives of adults, and I quickly realized this was her attempt to find me a boy friend.

I thought, I’ll give this Michael boy a chance. He talked about how he had lived in a very nice neighborhood in New Jersey, much nicer than the one we lived in, and told me that his father’s company had provided all the glass for the new United Nations building. I thought to myself, “This boy’s full of crap, and I have to take him down a notch.” He was very full of himself and clearly was seeking to impress. I approached relations with most boys with an air of studied disdain, but Michael Hunter had my hackles up immediately. I was unaware that the UN building had been erected in 1952 but I knew well enough not to believe him. I didn’t come straight out and call him a liar, but he could tell that I knew he was full of it.

One thing I was pretty sure I knew how to do was to be condescending to men and boys. Having three teenage cousins during the era of women’s lib had taught me quite a bit about sarcasm and just how far a good roll of the eyes could take you. These were the times when you couldn’t turn on the TV without a news report making reference to the women’s movement, Roe v. Wade, and the fight for the Equal Rights Amendment. Gloria Steinem was on with her frosted hair and wire-frame glasses, and Bea Arthur was starring in a sitcom called Maude in which her famous line was “God’ll get you for that, Walter,” which not only put her husband Walter in his place, but God in hers. My greatest role model on television was Cher. The Sonny and Cher Show always had a segment where Cher would one-up Sunny with her put-downs.

Any chance I got to show my finely honed skills at bitchiness was okay by me. I didn’t really think of it as being mean, I thought of it as having fun. Michael Hunter might have thought otherwise. I can’t remember what I said to him that first day in school, but I know I made him feel like shit. By the end of the day, I had definitely not made a new friend. Nonetheless, I had begun one of the most intense relationships of my early years.

In many ways, Michael was everything that I was not. Brash, confident, athletic, and charming in a guileless, almost needy, sort of way. He had brown hair, which got much lighter in the summer, brown eyes, thick eyebrows for a kid, and one unusual feature that we all noticed immediately: the last section of his index finger had been reattached. I forget how he lost his finger, and even if he told me it was probably a lie. I always said his mouth ran so fast he probably bit it off himself.