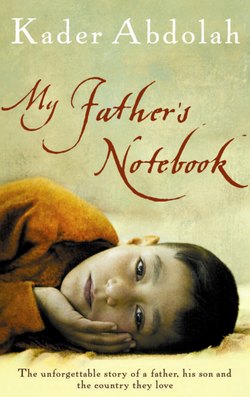

Читать книгу My Father's Notebook - Kader Abdolah - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Isfahan

ОглавлениеWe go to Isfahan with Akbar, where

we weave carpets. That and nothing more.

When night-time comes, we sit on the roof

of the Jomah Mosque and stare at the sky.

The Dutch poet P. N. van Eyck (1887–1954) believed that life was good and beautiful because it was filled with mystery and sorrow. One of his well-known poems is “Death and The Gardener”:

A Persian Nobleman:

One morning, pale with fright, my gardener

Rushed in and cried, “I beg your pardon, Sir!

“Just now, down where the roses bloom, I swear

I turned around and saw Death standing there.

“Though not another moment did I linger,

Before I fled, he raised a threatening finger.

“O Sir, lend me your horse, and if I can,

By nightfall I shall ride to Isfahan!”

Later that day, long after he had gone,

I found Death by the cedars on the lawn.

Breaking his silence in the fading light,

I asked, “Why give my gardener such a fright?”

Death smiled at me and said, “I meant no harm

This morning when I caused him such alarm.

“Imagine my surprise to see the man

I’m meant to meet tonight in Isfahan!”

A sombre poem. A sombre story. A sombre Akbar rode on horseback with Kazem Khan to a deserted station, where he left for Isfahan.

His uncle wanted him to leave Saffron Village for a few months, or even a few years. He had arranged for Akbar to stay with a friend of his in Isfahan.

Kazem Khan wanted to free him from the isolation of the village, which he thought was a suitable place to live only if you happened to be old or ill or an opium addict. It was time for Akbar to move on and meet other people. But where was the best place to send him?

Being an opium addict wasn’t easy. No matter where you were, you had to have a pipe, a fire in a brazier, a teapot, a special tea glass, sugar, a clean spoon, a carpet, and a safe but quiet place looking out over trees and mountains or some other pretty landscape.

That’s why the opium addicts needed each other. That’s why they kept in touch. All over the country they had friends and acquaintances with whom they were always welcome to smoke a pipe.

Kazem had many friends, especially poets and famous carpet designers. Men with high social standing. One of these men lived in Isfahan.

The train came in and Aga Akbar climbed on board. It was his first train ride. In his pocket he had all the information he needed: the name and address of his contact in Isfahan, his own address in Saffron Village and even the telegraph number of the sergeant in charge of the local gendarmerie.

Imagine leaving your birthplace for the first time and going directly to Isfahan, the city referred to as “half the world”. The city containing Persia’s oldest mosques. Centuries ago the builders had covered these mosques with beautiful azure tiles. The mysterious designs, numbering in the thousands, are so mesmerising that when you look upon them you no longer know where you are or what you’re doing there.

Behind the magical Naqsh-e-Jahan Square is an ancient cemetery, with tombstones dating back to the time of the Sassanids. This is the burial place of the Persian gardener, the one mentioned by the Dutch poet. On his tombstone, it is written: “Here lies the gardener, the man who momentarily escaped Death’s clutches.”

If you look to the left when you’re standing by the grave, you can see a tall cedar off in the distance. If you walk towards it, over an ancient stone path that meanders through a rose garden, you’ll eventually come out near a bazaar—the oldest in the country and the most beautiful in the Islamic world. That’s where you can see the most amazing Persian rugs. Hundreds of them are piled high in every store. In the rear there’s always a workshop, where an old, experienced weaver plies his trade. He doesn’t weave new carpets, but mends old ones. Expensive rugs are for sale in the bazaar. Sometimes these unique works of art get damaged, so there’s always an experienced carpet-mender—a craftsman—on the premises who can perform wonders with a needle and a few coloured threads.

In one of those stores there was a well-known carpet-mender named Behzad ibn Shamsololama. He had pure magic in his fingers. He also happened to be the man waiting for Aga Akbar at the station in Isfahan.

After twenty-three hours the train finally reached its destination.

Aga Akbar got out.

“When you get off the train,” his uncle had told him, “don’t go anywhere. Wait right there until an old man with glasses and a cane comes to get you.”

And that’s what must have happened, because years later a black-and-white photograph of a bespectacled man with a cane stood on the mantel in Aga Akbar’s living room. If you examined the picture closely, you could see faint traces of the word “Isfahan” on the wall behind him.

Aga Akbar lived in Isfahan for a year and a half. He worked from sunrise to sunset in the workshop at the rear of the store. When the store closed, he went to his sleeping place on the roof.

Isfahan made a lasting impression on him. In the years that followed he never missed an opportunity to broach the subject. If he happened to see an Isfahan carpet, he would say, “Look, this carpet comes from Isfahan. Have you ever been there?”

Or he would talk about the mosques. He would point up at the sky to describe the blue tiles of the Sheikh Lotfallah Mosque. A dome located defiantly opposite the dome of the universe.

To express his admiration for the ancient Jomah Mosque, he would pick up a brick, then drop it. This was his way of saying that the tiles used in the mosque had come from heaven.

When he talked about the bazaar, he would put his hand over his mouth and look around in astonishment. What he meant was that the magic carpets unfurled by the shopkeepers made your jaw drop in amazement.