Читать книгу All the Wild Hungers - Karen Babine - Страница 13

Оглавление5

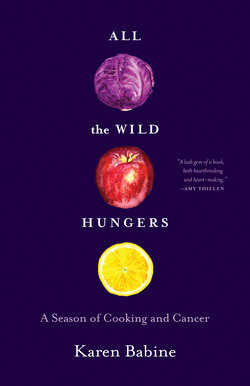

MY MOTHER’S SURGEON SAYS that the margins and lymph nodes are clear, but skepticism lingers between my ribs, a slight and constant pressure. Later, the poet Heid E. Erdrich introduces me to the concept of fetal microchimerism, the phenomenon of fetal cells being found in the mother decades after birth—“blood river once between you / went two ways / what makes us / own sole and sovereign selves / is only partially us,” Erdrich writes in “Microchimerism”—and I wonder what alternate selves mothers carry in wombs that betrayed them, what muscle memories remain in the phantom space left behind when children have been delivered, when the wombs themselves are gone, or what we carry in wombs that, by choice or circumstance, never bear children. Scientific American tells me, “We all consider our bodies to be our own unique being, so the notion that we may harbor cells from other people in our bodies seems strange. Even stranger is the thought that, although we certainly consider our actions and decisions as originating in the activity of our own individual brains, cells from other individuals are living and functioning in that complex structure”—and I cup my palms together to imagine what my mother’s three-pound cabbage-sized tumor would feel like, but the heft of my imagining disintegrates into the feel of my mother’s hand in mine while the doctor attempts a second biopsy, necrotic tissue floating darkly in clear tubes, learning later that the cells simply fell apart when pathology tried to look at them. But I don’t understand, not really. Are we our own unique beings or not? Science would suggest we are not. We exist within systems, networks, the matrix of family and friends, patterns. We are not alone. We are all connected, even on a cellular level, across time, space, and logic. Perhaps it is individuality that is the myth.