Читать книгу Unearthed - Karen M'Closkey - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеPREFACE

THE INCREASING PROMINENCE OF LANDSCAPE ARCHITECTURE OVER THE PAST TWO DECADES IS UNDENIABLE, DUE IN NO SMALL PART TO THE WIDESPREAD ATTENTION TO ISSUES OF SUSTAINABILITY AND THE SENSE OF URGENCY THAT ACCOMPANIES

our current environmental problems, which are now understood in a global context. Landscape’s centrality to addressing these issues—the form of future urban settlement, and the importance of ecological and recreational networks to guide such settlement—is becoming more apparent to those outside of the field, which has helped reestablish landscape architecture in the significant position it previously and deservedly enjoyed in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. However, such increased visibility of the discipline has been accompanied by a narrowing comprehension of its full cultural efficacy, due to the ways in which the terms “sustainability” and “ecology” have been uncritically adopted as the primary justification for the contributions that landscape architects make to the built environment. Certainly, landscape architecture is a “practical” discipline that engages the myriad social, political, and ecological realities that constitute our landscapes; however, landscape architecture is also a “projective” or imaginative discipline because it envisions the intersections among those realities in critical or challenging ways by making places that are unique, expressive, and experientially compelling.

Two recent developments have overshadowed these latter concerns. First, a turn in the profession that emphasizes “ecofriendly” or “green” design has resulted in a set of predictable responses to environmental sustainability, such as green roofs or constructed wetlands. The prominence of this utilitarian approach to function has eclipsed questions about how such approaches engage the equally relevant social, experiential, and symbolic functions of landscape. And second, academic discussions concerning “landscape urbanism” have gained traction among architects and landscape architects over the past decade. Its proponents claim that conjoining the terms “landscape” and “urbanism” frees landscape from being understood in counterpoint to the city (and attendant associations with remoteness, scenery, and nature). Here, ecology is constructively understood as an overarching metaphor for interconnectivity: by recognizing that every-thing is bound together by the same dynamic processes, we see that our cities are as ecological as our landscapes, our landscapes as manufactured as our cities. Given this desire to leave behind binary divisions between city and landscape, center and periphery, or culture and nature, it is unfortunate that the rhetoric of landscape urbanism has been polarizing in other ways by arguing that landscape architecture should be liberated from its “traditional” concerns (the most commonly named are form, composition, and representation) by subsuming it under a different rubric and, presumably, by engaging in different modes of practice. Landscape urbanism’s call for a “disciplinary realignment” raises important pedagogical questions in terms of what ideas (theory, history, techniques) we teach and, significantly, what defines a discipline’s efficacy, if not its expertise. This has yet to be seriously addressed in pedagogical or methodological terms, which is why landscape urbanism as defined in the North American context is simply landscape architecture “rebranded.”1 Landscape architecture is already broadly cross-disciplinary in practice; it was founded as a profession by combining practical knowledge drawn from a constellation of other fields—geology, forestry, horticulture, and so on—and is influenced by visual culture, philosophy, science, politics, and poetry. It engages this collection of influences in order to propose or challenge how ever-changing social, economic, and technological conditions might be engaged and experienced on the ground. It is, in fact, the ground—its specific material, historical, and formal potential—that is missing from much of the conversation surrounding sustainability and landscape urbanism today. This account of Hargreaves Associates’ work is a consideration of alternative strategies that in their turn critique these recent developments.

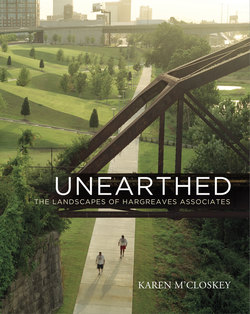

HARGREAVES ASSOCIATES HAS BEEN EMBROILED in the challenges of making public landscapes for almost thirty years. Its practice thus spans a time frame that has witnessed many changes both internal and external to the discipline. The aim of this book is to trace these shifts, utilizing Hargreaves Associates’ work as a vehicle in order to demonstrate how the utilitarian and infrastructural demands (hydrological, ecological, etc.) placed on landscapes can be engaged through vivid and precise design interventions rather than privileging one of these values at the expense of others. A second objective is to explicate the firm’s “geologic” design methodology, which incorporates diverse notions of strata—historical, material—to demonstrate its pertinence for dealing with the type of site conditions commonly encountered today, namely, the postindustrial landscape. Though landscape urbanism has, in the United States, been positioned as a response to the sprawling metropolis, which is characterized by a vast horizontal field that is automobile-dominated rather than by traditional definitions of city centers and building density, the sites vacated because of this horizontal expansion (old airports, industrial waterfronts) are exactly the types of locations that form the basis of projects most often referred to as exemplars of landscape urbanism, and they are the types of sites focused on in this book.

Given the prevalence of such sites today, we have entered a phase of park building that rivals the political momentum of the nineteenth century. This is an immense opportunity for landscape architects to engage in questions about the nature of public space, and the nature of “nature” as represented and constructed in urban landscapes, particularly because today’s site conditions are distinct from those of our predecessors. As George Hargreaves has said, the firm has never built on a greenfield site: there are no streams, no boulders, no forests, in other words, “no bones” on which to build its projects.2 Hargreaves Associates has taken advantage of these conditions to develop methods to physically and conceptually build complexity back into sites that have been stripped of their ability to support diverse uses. Consequently, this book is organized into three chapters that address different notions of fabricated ground—geographies, techniques, and effects—and includes an examination of three projects within each theme. The choice of projects cited—by landscape standards quite modest in size, ranging from eighteen acres to two hundred acres—is to focus on the specificity of a “middle scale” of site.3

The themed chapters are preceded by an introduction that situates Hargreaves Associates’ work with respect to the influences that were prevalent when Hargreaves began his practice. Given that earlier interpretations of the firm’s work are structured around terminology such as “process” and “open-endedness,” terms that have become more prevalent over the past two decades, the introduction traces how these ideas emerged with respect to that work. George Hargreaves and others have explained a shift in their approach as a move from a subjective engagement with process to a more intensive investigation of programming; however, this change is as much an indicator of the shifting nature and location of public park space and its funding as it is simply a reflection of the shifting intentions of the designer.4 Thus, the subsequent chapters include projects that span from the late 1980s to 2012 bringing into focus the consistent threads in Hargreaves Associates’ work that manifest differently in various projects, and that shift expression as externalities change.

The title of Chapter 1, “Geographies,” signifies the intersecting cultural, natural, and political forces that influence a region’s transformation over time. I use the projects in this chapter as microcosms of these broader changes, and underscore the challenges that landscape architects face when transforming sites for public use, especially in regard to postindustrial sites. The notion of public, collective life is presented in two interrelated ways: first, in how sites are places of collective memory; and second, in the changing definition and role of who constitutes the public. The projects chosen for this category demonstrate how public space is about representation—of people, of place—whether or not we claim it to be so. The first project is under the jurisdiction of the National Park Service (San Francisco’s Crissy Field), the second a state park (Los Angeles State Historic Park), and the third a downtown waterfront development (Chattanooga) that contains part of a National Trail—also a designation of the National Park Service. Consequently, these projects must address the needs of local residents while representing the aspirations for federal and state cultural landscapes.

The second chapter, “Techniques,” focuses on the relationship between technological and natural systems in order to demonstrate how the dynamic aspects of landscape are engaged via engineering and construction. The three projects in this chapter address water cleansing and control and are used to highlight the interface between landscape architecture and engineering. Guadalupe River Park illustrates the various, at times incompatible, definitions of “function” as it pertains to landscape, and demonstrates how different infrastructural systems can perform similarly in measurable ways without appearing identical. The other two projects, Sydney Olympic Park and Brightwater Wastewater Treatment Facility, are used to make a similar point by focusing on the inescapably aesthetic and ideological aspects of function.

The third thematic chapter, “Effects,” examines relationships among geometry, topography, and planting, and emphasizes the importance of form making to support a variety of conditions, experiences, and uses. The examples analyzed, Louisville Waterfront Park, the University of Cincinnati, and the Clinton Presidential Center Park, all use similar strategies for their organization. I discuss how form, material, and movement are orchestrated in the work, and how their various combinations constitute moments of awareness in the landscape where particular spatial or material attributes become legible. Working the earth to mold the ground is central to the landscape medium, and Hargreaves Associates’ facility in working with topography is fundamental to the effect of the work.

GEORGE HARGREAVES RECEIVED A BACHELOR OF landscape architecture from the University of Georgia in 1977 and his master of landscape architecture from Harvard University in 1979 under Peter Walker’s tenure as chair of the department. Hargreaves spent several years working at SWA, one of the incarnations of the collaboration between Hideo Sasaki and Peter Walker, before venturing out to form his own practice in 1983, initially named Hargreaves, Allen, Sinkosky & Loomis (HASL) and reincorporated as Hargreaves Associates in 1985. Hargreaves Associates office was first stationed in San Francisco, which remained their only location until Hargreaves became chair of the department of landscape architecture at Harvard University in 1996, at which time they opened their Cambridge, Massachusetts, office. After concluding his position as chair in 2003, Hargreaves opened a third location in New York City and, as of 2008, an office in London.

While George Hargreaves remains the design lead of Hargreaves Associates, the firm depends on the talents of other individuals, many of whom have been with the office for one or two decades. Of particular note are senior associate and president Mary Margaret Jones, who joined the firm in 1984 and has been instrumental in its direction, and former associate Glenn Allen, who was one of the founding partners of HASL.

THE IMAGES IN THIS BOOK ARE DRAWN FROM various sources, including images from Hargreaves Associates, images gathered from the agencies or corporations who manage the projects, my own photographs, diagrams drawn from information provided by Hargreaves Associates, and photos from users of their landscapes who post images on websites such as Flickr.com.