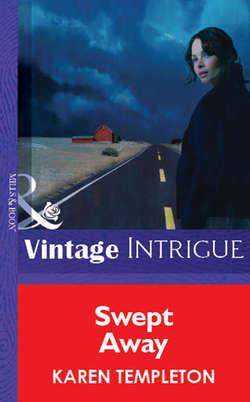

Читать книгу Swept Away - Karen Templeton - Страница 9

Chapter 3

ОглавлениеIt’d been a long time since a woman had made him lunch.

It’d been even longer since sex had tapped at the door to his thought and said, Psst…remember me? Okay, so maybe it had come a’knocking once or twice in the past three years, but for damn sure Sam hadn’t had the time, interest or energy to open the door. In any case, the problem with both of these events was that Sam didn’t need, or want, either one in his life.

On an intellectual level, at least. Which was the only level he was going to pay any mind, since listening to the alternative—which would be something not involving a whole lot of brain cells—was too darn scary to contemplate. Because right at this very moment, if he indeed removed his brain from the equation, he didn’t mind at all having somebody make him lunch. And he really didn’t mind that pleasant ache in his groin, if for no other reason than to be reminded that, hallelujah, brother, he wasn’t dead yet. But he very much minded not minding, because…well, because what was the point?

Although the way the gal was looking at him…

He heard the pipes shudder, then groan, as Lane turned on the shower. Meaning it would probably be a while before they had a buffer. One big enough to count, anyway, he thought with a glance at his youngest, wrestling on the floor with Radar and growling louder than the dog. So much for the clean hands.

“So—” The word popped out of Carly’s mouth like a blow dart, like maybe she’d been having similar thoughts. Sam realized he could see straight through that flimsy shirt she was wearing, and even though she had another shirt on underneath, the peekaboo effect was wreaking havoc on his common sense. “What’s with all the notes all over the place?”

Not what he expected her to say. But after a quick scan of the room, he could see why she’d asked. “Huh. Guess there are a few, aren’t there?”

“Twelve,” she said. “Not counting that.” She nodded toward the wipe-erase board.

Sam held one of the kitchen chairs steady so Travis wouldn’t knock it over as he climbed up into his seat. Kid was still too short to really sit at the table comfortably without a booster seat, but Sam had a better shot at getting him to eat worms than use the “baby chair.”

“Got tired of repeating myself, basically. And this way, nobody can claim they didn’t know what they were supposed to do.”

Carly took a seat at the table, her plate filled mostly with lettuce, it looked like. “And this doesn’t strike you as just a tad…autocratic?”

“Only way to go when you’ve got six kids. Unless you got a better idea?”

“Move?”

“Don’t think the thought hasn’t crossed my mind a time or two.” He handed Travis half a cheese sandwich. The kid gave him a wide smile, and Sam thought, with a little pang, This is the last baby-toothed grin I’ll see. “For what it’s worth,” he said, turning back to Carly, “your dad was impressed as all get-out.”

“He would be.” With a loud groan, Radar collapsed on the floor in front of the sink, clearly untroubled by his status as wuss dog of the family. “Although,” Carly was saying, “Dad never resorted to notes or lists. He tended to rely more on the bellow and glare method.” Then her mouth quirked up. “With good reason.”

Yeah, Lane had shared a few stories about his daughter. Stories he doubted Carly would appreciate being bandied about, Sam mused with a smile as Henry, an ancient, chewed-up-looking tomcat whose few waking hours these days were mostly devoted to tormenting the dogs, paused in his travels to sniff Radar’s butt. The startled dog leaped to his feet, only to immediately cower against the cabinet door, ears tucked against his skull, eyes wide with terror. Satisfied, Henry flicked his tail and stalked off. Travis giggled; Carly gave the little boy a smile softer than Sam would have thought possible, given the sharpness of her features.

“Yeah,” he said, unable to take his eyes off that smile, “Lane definitely gave me the impression that you were a bit of a handful.”

She smirked. “Are you kidding? I made his life a living…” She glanced at Travis, then back at Sam, her eyes glittering, defiant, like her makeup, which, while anything but subtle, ventured no where near tacky. This was simply a woman who had no qualms about making herself look good. “Let’s just say I took the concept of challenging authority to a whole new level. Which begs the question…” She swept one arm out, indicating the notes. “Does this work?”

“Mostly. Once everybody realized I meant business.”

“And how old’s your daughter?”

A cold, clammy chill tramped up his back. “Almost fifteen.”

All she did was smile. And change the subject, her smug expression clearly indicating her belief that she’d won that round. “So. You get that fence fixed?”

“You’re still doing it, aren’t you?” Sam said.

A bite of salad halfway to her mouth, her eyes shot to his. “Doing what?”

“Challenging authority.”

She shrugged, the gesture setting the dangliest of the earrings to shimmering. Her hair, a rebellious tangle of not-quite curls swarming around her neck and shoulders, strained against the single bright blue clip jammed impatiently at one temple. “Can’t say as I’ve ever been real big on following the rules, no. So. The fence?”

Sam found it curious that, for someone so intent on being a badass, she sure didn’t seem interested in discussing it. But no matter, especially as it was none of his concern, anyway. “All done,” he said, loading up his own plate with several sandwich halves before turning back to the refrigerator. Carly’d already poured Travis a glass of milk, but Sam wanted iced tea. Preferably dumped over his head. “Thanks to your father. Can’t remember the last time I saw anybody get such a kick out of replacing fence posts.”

“Yep, that’s Dad.” Sam noticed how cautiously she was eyeing the four-year-old, giving him the feeling she didn’t spend a lot of time around little kids. Then she picked up a napkin and wiped a dribble of milk off Trav’s chin, which earned her a shy smile. She smiled back, sort of, then forked in a bite of lettuce and said, “So I guess that means the two of you didn’t spend the whole time discussing my errant ways.”

“Not the whole time, no. Just on the ride there. And back. And whenever we got close enough to hear each other.”

She reached out to move Trav’s cup of milk back from the edge of the table. “I wouldn’t’ve thought there was that much to discuss.”

“And here I was thinking it sounded like he’d barely scratched the surface.”

That got another moment’s stare before she said, “Anyway…I think Dad’s missed working with his hands.” Sam checked out hers—long fingers, smothered in all those rings, but no nail polish. “Mom was convinced he’d bought an old house on purpose so there’d always be something to fix. And believe me, there was. The kitchen alone took the better part of a year.” She smiled. “I swear, all the clerks at Home Depot knew him by name.”

“Sounds like a man after my own heart,” Sam said, and she rolled her eyes, making him chuckle. But her smile dimmed as she stabbed at a hunk of lettuce.

Travis asked for another sandwich half. Carly beat Sam to it. “Doing nothing makes him crazy. After he retired from the Army, he started his own security business. Except when Mom got sick, he sold it so he could spend as much time as possible with her. Then after she died, he got rid of the house right away and moved into an apartment. I understand why he did what he did, but he’s been at loose ends ever since.”

Sam waited out the twinge of sadness, faded more than he would have ever believed possible three years ago, but not entirely gone. For a moment, he almost envied the other man, being able to cherish what he had, to say goodbye. Losing Jeannie so suddenly had been like being shoved off a cliff into an ice-cold waterhole—there was no time to get your breath before you had all you could handle just to keep from drowning. But as hard as Jeannie’s unexpected death had been on him and the kids, at least she hadn’t suffered. Watching somebody you loved dwindle away…he could only imagine how hard that must have been. “Too many memories in the house?” he finally said, as his own echoed softly from every nook and cranny of the one they were sitting in.

“That’s what I figured, but he never really said.”

“I’m done,” Trav piped up. “C’n I be ’scused?”

Sam said, “Sure,” and the kid slid down from his seat, his feet hitting the floor with a thump before pounding out the back door, Radar—having recovered from the cat’s brutal attack—hot on his heels. The screen door whined shut, leaving him and Carly alone. Together. With the water still humming through the pipes and Sam well aware that voicing Lane’s probable motivation for selling his house could possibly let Carly more into his own head than he might like, especially since a few of those memories now whistled through his brain like wind through a canyon. With some difficulty, Sam swallowed the bite in his mouth and said, “Your dad must be bored out of his mind. In an apartment, I mean.”

She gave him one of those looks that women do when they’re trying to translate what you just said into their own language, then nodded.

“You have no idea,” she was saying, taking another bite of lettuce, her posture bringing to mind the deceptive strength of a sapling.

“So you decided what he needed was a road trip to jump-start him again.”

“Both of us, actually. Although when I brought it up, Dad definitely pounced on the idea.”

“How long’ve you been on the road?”

“About a month.”

“Since you lost your job?”

“That happened about three months ago, actually. Which is when the sports doctor told me I could have surgery, with no guarantee I’d ever dance again anyway, or quit dancing altogether and the problem might clear up on its own.”

“Some choice.”

“Yeah. That’s what I thought.”

Her bravado wasn’t doing a particularly hot job of masking her disappointment. “And how long until you go back home?”

“We hadn’t decided that. One of the perks of being in limbo,” she said with a grand wave of her fork. “I’ve got a half offer from an old dance school friend who’s married with munchkins and the minivan and the whole nine yards in a Chicago suburb, she wants to open a dance school and wondered if I’d be interested in teaching.”

“Are you?”

That bite of lettuce finally found its way into her mouth. After several seconds of chewing, she shrugged. “It’s an option.”

The pipes groaned again, this time from the water being turned off. “But…not one you’re very excited about.”

“Hey. I’m thirty-seven. Even without my knee sabotaging me, I only had maybe five good years left, anyway. Eight if I didn’t mind pity applause,” she said with a short, dry laugh. “Still. Somehow, even though most dancers turn to teaching after they retire, I somehow never saw myself doing the Dolly Dinkle Dance School routine. Teaching a class full of everybody’s precious darlings in pink leotards and tutus… I can’t see it, frankly. I’m not really into kids.”

Sam thought of her wiping Travis’s chin and smiled to himself. “Yeah. I can tell.”

“It’s not that I don’t like them,” she added quickly. “Exactly. I just never quite know what to say to them. How to relate to them. I mean, my biological clock’s merrily ticking away and I’m like, ‘Fine, whatever.’ Shoot, it’s all I can do to take care of myself.”

Chuckling, Sam polished off his last sandwich, then chased it with the rest of his iced tea. When he finished, he leaned back in his chair. “You always this up-front with people?”

She shrugged. “Pretty much. Does it bother you?”

“It’s a mite unnerving, but no. Not particularly. Actually it’s kinda nice to be around someone who has no trouble saying whatever’s on her mind.”

“Most men wouldn’t agree with you.”

“That’s their problem,” he said mildly. “So tell me about your dancing.”

Brows lifted. “This isn’t a date. You’re not going to win any points by pretending to really be interested in what I do.”

“Humor me. It’s not every day I have an honest to God ballerina sitting in my kitchen. And I’d add ‘eating my food’ but that would be stretching it.”

Her eyes followed his to her plate. “Ah,” she said, with an understanding smirk, before her shoulders bounced again. “I’m not anorexic, if that’s what you’re thinking. I ate like a pig at breakfast, that’s all.”

“What? A piece of toast and a grapefruit half?”

“Hah. Three pieces of French toast, sausage and two scrambled eggs.”

“I’m impressed.”

“So was what’s-her-name. The woman who runs the place?”

“That would be Ruby.”

“Ruby, right. She wanted to know where I’d put it. Anyway…you sure you want to hear this? Okay, okay,” she said when he let out an annoyed sigh. “Not sure how much there is to say, really. I’ve been dancing literally since I could walk, even though I didn’t start formal training until I was ten and Dad retired, so we weren’t moving every five minutes. I went to dance camp as a teenager, then on to North Carolina School of the Arts for high school. After I graduated, I danced with a major New York company for a couple of years, which for anybody else would have been a total dream job. Except I realized that staying there would have meant basically dancing in the chorus of Swan Lake for the rest of my career. So I decided I’d have more opportunity in a smaller regional company, even if it meant a cut in pay. Never expected to end up back in Cincinnati, but there you are.”

On the surface, her words seemed straightforward enough. And yet, something about the way she wouldn’t look at him, the fingers of her left hand constantly worrying the edge of the plastic placement the whole time she was talking, led Sam to wonder if that part of her life had really been as straightforward as she was making out.

He took another bite of his sandwich before saying, “You ever regret your decision? To leave the bigger company?”

“No,” she said immediately. “See, dancing isn’t something I do, it’s who I am. Not that I expect anyone else to understand that. I mean, how much sense does it make to be so passionate about something that pays squat, that leaves you in virtually constant pain, and offers zip job security?”

“Sounds an awful lot like farming.”

She grinned. “Hadn’t thought of it that way. But hey—at least farming feeds people.”

“Who’s to say what you do doesn’t feed people, too?” he said, and a rich, startled laugh burst from her throat. “What? You think a country boy can’t appreciate the arts?”

Her laughter died as another blush crept across her cheeks. “Well, no, but—”

“Hey, the tradition of farmers letting loose with music and dancing goes way back. Why is it you suppose that whole wall out there’s covered in the kids’ artwork? And why else would I put myself through the torture of listening to a twelve-year-old murder the violin for a half hour every day? Or scrape together a few extra bucks so one or the other of ’em can take a special art class or music class after school? Maybe it’s not ‘art’ in the way a lot of folks define it, but whatever it is, it’s not something tacked on—it’s just the way people are wired.” He allowed himself a second or two to stare into those wide eyes, then said, “Not what you expected, is it?”

She blinked. “No. Not by a long shot.” Lowering her eyes, she poked at her salad for a couple beats, then looked at him again. “So. Do you dance, Sam Frazier?”

“I’ve been known to do a mean two-step in my day.”

Again, that wonderful, rich sound of her laughter filled the room, like something that had been let free after being confined for far too long. Then their eyes locked and need kicked him in the gut, swift and hard, and man, was he ever glad to see Lane.

“Well,” Sam said, rising, “I reckon I’ve goofed off long enough. Still got a ton of work to do before the kids get home from school. Thanks for lunch,” he said with a nod, grabbing his hat off the rack and screwing it back onto his head. “And if either of you need to go into town or want to go sightsee or something, feel free to take the Econoline. Keys are on the rack over there.”

A week, he thought, striding out to the barn. Surely he was strong enough to last a week.

Only then a little voice in his head said, Don’t bet on it, and he thought, Oh, hell.

She could make it through one lousy week, right?

A single week. Seven piddly days. Maybe less, if the axle came in earlier…

“You sure your knee’s okay?”

Which made at least the sixth time her father had asked her this since they’d set out on their walk around the property. His idea. One her knee actually hadn’t been in total agreement with, but she knew she’d be okay as long as she took it easy. Staying in that house, however, was another matter entirely.

“This isn’t exactly like running the marathon, Dad. I’m fine.”

A loud, obnoxious cackle sounded inside her head.

“And I know you,” Dad said. “Used to drive your mother and me nuts, the way you wouldn’t admit defeat if your life depended on it.”

Well, maybe not out loud. Because she was definitely feeling, if not defeated, certainly poleaxed.

By a quiet, soft-spoken farmer with six kids. And how messed up was that?

She simply wouldn’t think about it, that’s all.

Carly laughed, the sound maybe a little shriller than it should be. Her father gave her a funny look. “You know me well. But really, it’s okay. Actually,” she said, realizing with moderate panic that attempting to not think about Sam was like trying to get gum out of her hair, “I’m kind of surprised you suggested this. I would have thought you’d be all worn out from this morning.”

Eyes like deep ice cut to hers; chagrin toyed with his mouth. “Because I’ve got one foot in the grave, you mean.”

“No, of course not—”

“I’m only sixty-three, Lee. Not ready for the home yet.”

She smiled. True, the morning’s outing seemed to have done her father a world of good, provoking a pang of guilt that she hadn’t been pushier about getting him out and doing long before this….

Did you see the way Sam kept looking at you?

Shut up, she said to…whoever. The spook squatting in her brain, she supposed. Except the spook cut right back in with some annoying observation about how Sam was like some innocuous-looking Mexican dish—wasn’t until you’d taken several bites before you realized your hair was on fire.

Of course, this is not a problem if you like spicy food.

“Lee? Are you okay?”

“Yes, Dad,” she said with a bright smile, because whatever this craziness was, talking it over with her father wasn’t gonna happen. Actually, up until this little trip, it had been years since she and Dad had talked about much at all. Not because they didn’t love each other, but because they did. At some point several years ago, after what Carly assumed was a mutual revelation that they came from different planets, and that they’d both grown weary of every conversation degenerating into an argument within five minutes, she’d simply stopped bringing up touchy subjects. Which mostly involved her vocation (he tolerated it, but had clearly hoped it was a phase and that eventually she’d come to her senses and pursue a “real” career), her lifestyle (enough said), and her love life (about which, for everybody’s sake, her father knew far less than he thought).

Fortunately her mother had been more inclined to take Carly’s side—the natural outcome, Carly supposed, of Dena Spyropoulos Stewart’s having been brought up in a strict Greek-American family with a father who exerted an iron-fisted control over his wife and children. And since Lane was totally besotted with his wife, he usually lost the battles with his hardheaded daughter. Without her mother to run interference, however, Carly frankly hadn’t been as inclined to seek out her dad’s company. Realizing you simply weren’t the child your father always thought he’d have had tended to have that effect on a person. In fact, part of her problem with Sam—aside from the farmer with the six kids business, which was a deal-breaker in any case—was how much he reminded her of Dad. All those notes and lists brought back way too many memories, most of which involved her father expecting her to do things one way and Carly’s determination to do exactly the opposite.

So it had been easier, especially after Mom’s death, to simply stay out of each other’s way rather than enduring visits that neither of them really enjoyed very much. Not something she was proud of, but there it was.

And only the threat of either, if not both, of them disintegrating into pajama-clad blobs spending their days watching game shows and infomercials had spurred her—in a moment of pure insanity—into suggesting they take this trip. Especially considering the odds of their killing each other within the first forty-eight hours. What they’d discovered instead was that, somewhere along the line, they’d both mellowed. Not that they now shared a brain or anything, but at least enough to enjoy each other’s company.

Especially during those long, lovely periods that people referred to as “companionable silence.”

The countryside in this part of Oklahoma tended to be hilly, nestled up against the Ozarks the way it was, and Sam’s farm was no exception. The spread wasn’t particularly large, her father said, fifty acres or so—but Sam was determined to wring every drop out of the land he could. Dad explained that the larger fields were devoted to wheat, alfalfa, and corn, with a large vegetable garden that yielded not only plenty of produce to feed the family, but enough left over to sell at a local farmer’s market as well. Then there were the fruit trees—three kinds of apple, not to mention pear and cherry—the chickens, the cows, the two pairs of hogs that produced several litters a year…and plenty of pork in the freezer, he added.

Carly shuddered, which got a chuckle. “That is what farming’s all about, you know.”

“Yes, I do. It’s just all a little too hands-on for me.”

“You loved it as a kid.”

“Gram and Gramps had a dairy farm. They milked the cows, they didn’t eat them.”

“No, they ate somebody else’s. And where do you think those fried chicken suppers came from? KFC?”

“Dash my idyllic childhood memories, why dontcha?”

Her father laughed, a good sound. The sound of someone on the mend, she decided.

They’d come to a fallow field smothered in late season grasses and wildflowers. A lone oak alongside another farmer’s post-and-rail fence, its side scarred from a long-ago lightning strike, beckoned them to rest a while. Carly’s knee was more than ready to take the tree up on its offer. They lowered themselves onto a patch of cool dirt, both taking long drinks from their water bottles. At a comfortable distance, a pair of cows munched, their ears flicking, tails swishing. One of them disinterestedly looked in their direction.

“Your mother would have loved it here,” Dad said. “The mountains, the trees…she used to say there was nothing finer than the smell of country air.”

“If you like earthy.”

“You’re too young to be so cynical,” her father said mildly, twisting the cap back on his water, and she thought, Young, hell. I feel as old as these hills.

And very nearly as worn down.

But truth be told, some of her best childhood memories had come from summers spent on her grandparents’ farm. Except that was then and this was now, and that little girl had up and taken off some time ago.

Leaving in her place a cynical, lame woman destined to become a dried-up old prune of a dance teacher with dyed black hair and too much eye makeup who still wore gauzy, filmy things in an attempt to fool herself that she was still young and lovely.

There was a heartening thought.

“I’m glad you suggested this,” Dad said.

“The walk was your idea, remember?”

“Not the walk. The trip.”

Drawing up her legs to lean her forearms on her knees, Carly angled her head at her father. “Even though I drove the truck into a ditch?”

“Especially because you drove the truck into a ditch.”

“You know, you might be more ready for that home than you think.”

Dad laughed. “What I mean is, this gives us an excuse to stay put for a few days. Absorb some of what we’re seeing. Get to know the people who live here.”

Oh, yeah, a definite selling point. Carly turned around to stare at the cows. They stared back. Sort of. “I suppose,” she said, mainly because she didn’t want to argue.

“Guess we’re both at a sort of crossroads, aren’t we?”

Since that sounded a heck of a lot better than dead end, she said, “Yeah. Guess so.”

Her father took another swallow of his water. “You got any idea yet what you’re going to do when we go back?”

A logical question from a man who’d—logically—expect his thirtysomething daughter to, you know, have a plan? Since she no longer had a job? Never mind that it now struck her, like the proverbial bolt of lightning, that she’d apparently suggested this trip in order to avoid thinking about The Future. And now here The Future was, planted in front of her like a used car salesman, refusing to go away until she at least sounded as though she’d made a decision.

But she’d gotten real good at faking out her dad over the years. Goading him was one thing. Worrying him was something else, she thought as a surprisingly cool breeze sent a shiver over her skin. Dad had no idea how much about her life she’d chosen not to let him find out. A situation she had no intention of changing.

“I thought I’d see about teaching at the company school.” Actually she hadn’t, not yet, but it sounded good. “And you know Emily offered me a job.”

“That’s in Chicago, right?”

“Right outside. Lake Charles.”

“Gets damn cold up there.”

“Oh, and like Cincinnati’s so tropical?”

“I’m just saying.”

Saying what was the question. But, as she was so good at doing, she turned the tables on him. “What about you? Planning on going out for canasta champion at the Senior Citizen center?”

Lane blew out a half laugh, then shifted to lean against the tree trunk. It seemed strange, seeing her father so relaxed. Not bad, just strange. “Actually bumping along on all these back roads the past month must’ve jostled something loose in my brain, because I’m thinking of starting up some sort of consulting business. Something I could do from home, mostly, by computer.”

Well, hell—this was the first positive thing to come out of her dad’s mouth since Mom’s death. “Seriously?”

“Yep.”

“That’s a terrific idea, Dad.”

“Seriously?”

“Seriously.”

His gaze sidled to hers. “You could help me, you know.”

“Oh, right. Doing what, for God’s sake?”

“Haven’t figured that part out. But I’m sure we could think of something.”

“Dad. What on earth do I know about business?”

“You’re a smart cookie. You’d catch on.”

“Man, you weren’t kidding when you said you knocked something loose.”

“I’ve always thought you were smart, Lee. It was just your common sense I had issues with.”

“A subject I gather you brought up to Sam,” she said before she even knew the words were in nodding distance of her brain.

Dad skimmed a palm over his short hair, looking everywhere but at her. “Your name might’ve come up once or twice.”

“By whom?”

“I don’t remember, actually. What difference does it make?”

“None, I suppose. Except I’m not sure I appreciate being described as a ‘handful’ to a total stranger.”

“As if the man wouldn’t have figured that out on his own after five minutes in your company. Besides, don’t tell me you’ve haven’t always prided yourself on being a pain in the can.”

This was true. Except she was beginning to wonder how, exactly, this had benefited her in the long run.

She got to her feet, prompting a “You ready so soon?” from her father.

“My butt’s going to sleep sitting on the hard ground. And I’m getting cold.”

Her father rose, as well, slipping off his lightweight overshirt and handing it to her. “Thanks,” she muttered, poking her arms through the sleeves. The shirt fluttered around her, cocooning her in his scent, and she felt, just for a moment, like the little girl who used to love cuddling with her daddy before she turned into the big bad pain in the can.

Back when she still let people all the way in.

They started back toward Sam’s house, both lost in their thoughts. It had been a long time since she’d wanted to let anybody in, she realized. She wasn’t sure she knew how, anymore. Or even if it was worth it. But there had to be something more than this chronic emptiness, an emptiness that seemed to yawn wider with every affair, every pointless relationship. Yeah, she’d lived life her own way. And still would, hardheadedness being definitely a chronic disease. But perhaps it was her definition of things that needed tweaking.

Maybe.

Through a stand of pines, Carly spotted a pair of buildings, apparently belonging to another farm. Although she had the feeling nobody lived there, the barn—an old-fashioned number in soft grays—appeared fairly sturdy. The house was something else again. To Carly’s dismay, she realized she felt a lot like that house—old, abandoned and half-eaten up with decay. Terrific.

They returned by way of the front road, right as the big yellow school bus pulled up, its hydraulic brakes letting out a groan like an old woman taking off her girdle. The doors slapped open, belching out four buzz-cutted boys of assorted sizes, all in jeans and T-shirts and sneakers, still-new backpacks slung by a single strap across a skinny shoulder or dangling from one hand as they hurled good-natured insults back at their buddies still on the bus. The doors squealed closed; the bus let out a fart of exhaust and continued on, as the boys turned up the road leading to the farm, totally oblivious to being followed. Not surprising, since they were far too busy swinging their backpacks in a wide arc as they spun around, or bumping each other off balance, or yelling, “You take that back!” and “Nuh-uh!” and “What do you care, he’s stupid, anyway,” their soprano voices still high and clear and—God help them all—shrill as nails on a blackboard.

Then, like a turbocharged beetle from a fifties sci-fi flick, a metallic green Mitsubishi Eclipse roared past, kicking up a cloud of peach-colored dust and provoking the older boys’ taunts of “Libby’s got a boyfriend, Libby’s got a boyfriend!” Carly caught a glimpse of long dark hair, sucked out of the window along with some remark or other, which turned the taunt into “Oooh, I’m gonna tell!”

They were close enough to the house by now to have alerted the dogs, who streaked down the road to greet the dusty, noisy little group with blurred tails and sharp barks, one or two dashing back and forth from house to boys to house to boys, as if not trusting the boys to find their own way home. The seen-better-days Eclipse screeched to a stop in the yard; a teenage girl got out, her gaze longingly following the car as it did a three-point turn and zoomed back up the road, past Carly and Lane again. The boy inside spared them a brief, curious glance, just long enough to understand the reason behind the girl’s pining look.

Then Sam came out onto the porch, and Carly was defenseless against her stomach’s little whoomp at seeing him again, this unassuming, unremarkable farmer who moved with the unconscious ease of a person who has far more pressing things to think about than his own body. Or the crazy woman gawking at him, Carly thought with a sigh as a sharp whistle knifed through the air, bringing all shenanigans to an immediate halt. She couldn’t hear what he said, but five heads swiveled in her and Dad’s direction. When she and her father got closer, the boys all said, “Hello,” with various degrees of interest and enthusiasm as Sam introduced each one in turn. As if she’d remember all their names.

“And this is Elizabeth, my only girl. But everybody calls her Libby.” He put an arm around the pretty girl’s shoulders and gave her a squeeze. “I told Carly she could bunk with you for a couple of days, since you’ve got an extra bed and all. Didn’t think you’d mind.”

With a smile, Carly turned to Libby…and nearly lost her breath.

Never mind that she and Libby Frazier looked nothing alike, not in body type or coloring or stature. And yet, a single glimpse into those warm brown eyes, and Carly felt as though she’d been slammed back more than twenty years…

…to meet her fifteen-year-old self.

Somehow, Carly doubted it would be a joyous reunion.