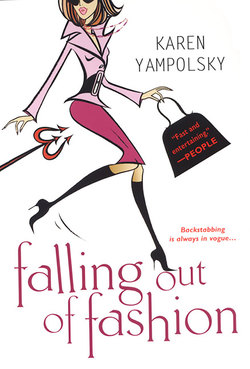

Читать книгу Falling Out Of Fashion - Karen Yampolsky - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

2

ОглавлениеLocal Girl Awarded Full Scholarship to Connecticut Prep School

—Athens Daily Banner, August 1979

Yet another unsuccessful fertility treatment. And yet another not-so-veiled threat from the Stepford Twins. It was shaping up to be a great day.

To take my mind off the failed fertility treatment, I focused on my interaction with Ellen and Liz, which plunged me into a real depression. I thought of that Talking Heads song “Once in a Lifetime” with David Byrne’s bewildered voice questioning: “How did I get here?” Thinking on it sent me back to the darkest period of my life.

I was fourteen, fresh out of a commune in rural Georgia.

Yes, a commune. Not the David Koresh, religious cult kind. It was a hippie, antiestablishment, grow-our-own food, conserve-energy, homeschool-our-kids kind. And it provided a somewhat happy, if unorthodox childhood, for me and my younger brother, Alex.

My parents were from the Northeast. They met when they were both on the tenure track at Yale—Mom as an art instructor, Dad as a philosophy professor. At the encouragement of one of their mentors, they left the rigidness of academia behind for communal life on a farm right outside Athens.

Whenever I think of my mom in those days, I picture her in low-slung hip-huggers with her hands caked in mud. She had long, straight blond hair; a perpetual tan; and deep, thoughtful dimples that came out whenever she concentrated really hard, like when she was working clay.

Pottery was her first love. I honestly think she enjoyed tossing pots more than spending time with Dad, me, Alex, and all of us combined. She would spend hours in the pottery shed, and sometimes I thought if we didn’t go in to get her she wouldn’t sleep, eat, or do anything else. When we would distract her from the spinning wheel, she’d seem like she was emerging from a coma, blinking and staring at us, like she had no idea who we were. The funny thing was, very few of those pots would actually make it to the kiln. Many of them sat unfinished, air-dried, and crumbly, lining the shelves and waiting for what, I never knew. I don’t think Mom knew, either.

Dad was covered in hair. He had a head of brown spirals that reached down to his shoulders; a chestnut coat of fur on his chest; and a bristly russet beard and mustache, which made his piercing blue eyes stand out even more. He had an offbeat sense of humor, a strong mischievous streak, and a quick and articulate tongue. He loved to get in tête-à-têtes with anyone who would listen. When the others at the commune became weary of his rantings, Dad would pull on his tweed blazer with the elbow patches—his only blazer—and go over to Athens and engage local students in his favorite coffeehouse. Sometimes he’d be gone for a day. Sometimes he’d be gone for a few days. But he’d always come back from those jaunts elated and rejuvenated. Whenever we would happen to be in town with him, young girls would rush up to greet him. “Hey, professor,” they’d call between giggles, even though he wasn’t one—at least not anymore. Not that Dad was a liar. But his ego would allow him to pad the truth a bit, and I knew those young girls were tasty feed for that hungry ego. Mom knew it too, though she’d go throw some pots and forget.

Dad was a great teacher, though, and schooling on the commune was probably far superior to that of the average public school. Not only did we learn all of Shakespeare’s plays by the time we were eleven, but we honed our math skills, debated politics, painted, drew, sculpted, built, and fished, which was my favorite thing to do.

Whether I’d go out in our self-made rower with Dad, Alex, or alone (despite her earthiness, Mom had prissy tendencies when it came to fish guts), I found fishing to be the best escape of all. It was quiet. It was challenging. Everything except the mossy lake seemed far away and unimportant. And it was the one time when I felt completely myself, comfortable in my skin. Plus, there was nothing like landing a bass or a trout bigger than Alex’s, and basking in Dad’s proud smile.

But communal life wasn’t all idyll. Deep down, I knew both Mom and Dad believed that it could provide a better, simpler, more tolerant, more equal, less evil life than the outside world. But no matter how much they tried to shun reality, it would inevitably creep in.

Work on the commune could be tiring. And as tolerant and mellow as everyone tried to be, there were frequent squabbles. During those times, Dad would talk about moving into town. But most of the townspeople weren’t welcoming to having people like us as neighbors. The university set were the only people in town, in fact, who wouldn’t mutter “dirty hippies” when we passed by. The problem was that housing near the university was expensive.

So we stayed put, probably for much longer than we should have. To cool off from disputes with the others, or just to remedy their restlessness, my parents would simply take off, sometimes for days on end. They’d drive miles to see a Grateful Dead show or leave to join a protest. Many times we had no idea where they were going, but we always knew why they left. And although Alex and I felt comfortable with the others on the commune, we still couldn’t help but feel left behind.

Through it all, my parents never let go of the esteem of academia, which is why they encouraged me to apply to northeastern prep schools. “You need to see the world in other ways, too,” I remember Mom saying, perhaps a little too urgently.

“You can always come back, if you want,” Dad pointed out. “But you need to go beyond the bubble. A great education starts with seeing all views. And there’s a lot to be said for a good education,” he’d add wistfully, making it clear where he’d rather be. I wondered if their sending me off was fulfillment of their lost dreams. It was almost as if they were too committed to the communal lifestyle, or too proud to admit that it might not be working as they had hoped. More likely, I think neither of them had the energy to leave for good.

In spite of everything, I was proud of my upbringing; I still get sentimental about it even today. Too many times in my life I have become homesick for its simplicity—which is ironic because soon after my acceptance into prep school, I resented everything about it.

My parents couldn’t have been prouder when I received a full scholarship to Hillander, the exclusive Connecticut prep school that was the alma mater of dozens of presidents, captains of industry, and Pulitzer Prize–winning writers. Though I doubted I would eventually fall into any of those categories, I was optimistic about the opportunities that were sure to come along. Even more exciting was the fact that I had never been around so many people my age. I was eager, and ready, to make a lot of friends.

It didn’t quite turn out that way.

On the day I left the commune, my parents loaded me, Alex, and my duffel bag into their junky old van and we drove all the way from Athens to Washington, D.C. My parents and Alex stayed there for an antinuclear protest. I went to Union Station and got on a northbound Amtrak.

When I arrived in Connecticut at the station nearest Hillander, I asked the ticket clerk for directions and I walked three miles to campus. Along the way, I admired the golds, oranges, and browns that stretched along the tree-lined sidewalks, and I liked the crispness of the autumn air and how the wind caused the leaves to swirl around my feet. I have no idea how long it took me to get to campus, but I do remember the awe I felt when I arrived.

The towering gray stone buildings with venerable ivy-covered walls were just like the academies I pictured from books like A Separate Peace and Catcher in the Rye. I noticed a group of clean-cut boys crossing the quad on a tour, and I wondered which one would become my Holden Caulfield.

Everything was so different from Georgia. It was colder, for starters. I noticed that the people moved in a quick, serious manner, not slow and ponderous, like at home. Though it was fall, there was still plenty of greenery on the grounds, but whereas Georgia was emerald, Connecticut was pine. The dissimilarities alone showed me that I certainly had a lot to learn. But that was okay, because I loved to learn. I was hungry to know the world beyond hippie communes.

My excitement quickly melted away, however, the minute I arrived at my dorm. I’ll never forget the looks on the faces of my roommate and her parents when I stepped in the door.

“Hi! I’m Jill!” I said excitedly, as I tossed my duffel on the floor.

Their expressions displayed a combination of fear, horror, and having eaten bad shellfish.

“You must be Alissa,” I went on, despite the awkward silence.

“Yeah,” the girl answered numbly, as she and her mother simultaneously looked me up and down. Alissa was all angles and edges: straight, blunt-cut blond bob, with each hair perfectly aligned; sharp but pretty features—pointed nose, prominent chin, triangular cheekbones, big square white teeth. She was topped off by confident, narrow shoulders helming a tall, thin frame, and if it weren’t for her giant, round boobs, we probably even would have worn the same size.

But I was flat as a board and much more reedy all around. Plus, it didn’t look like we shared the same taste in clothing. Alissa wore a perfectly pressed plaid skirt and a neat navy crew-neck sweater. That, combined with her mother’s Chanel suit, and her father’s sweater-vest and bow tie ensemble, made my Goodwill turtleneck and carpenter pants look even more ratty.

“We’re the Fords,” her father politely said, snapping out of his own fugue state. “Of Boston.”

“Oh,” I said. “My parents were in Boston last year. For a Dead show.”

I noticed Alissa stifle a giggle then, as her mom opened the door and peered into the hallway. Her expression was more perplexed than ever when she pulled her head back in. “And where are your parents, Jill?” she asked.

“Oh, they’re in D.C.,” I explained. “They dropped me off at the train station there.”

Mr. Ford blinked. Alissa looked at me like I was growing another head. And Mrs. Ford’s face again went the fear, horror, shellfish gamut.

“Alone?” Mr. Ford asked. “You came up here alone for your first day of prep school?”

I didn’t see the big deal. I was used to doing things on my own. “Sure,” I answered weakly. Then I turned my attention to unpacking, trying to focus on anything but their stares.

Alissa and her parents did the same, diving into six suitcases and several large boxes. There was a bag of hair products, accessories, and styling tools; another bag of nail polish, compacts, lipsticks, and creams. There was one big bag just full of shoes—clogs, boots, loafers, sandals, sneakers, flats, pumps, slippers, and even golf shoes.

And then there were the clothes. Dozens of sweaters in colors I never knew existed. Skirts—short, long, midi. A dozen firmly pressed khakis, all the same color. Hangers full of starched oxford blouses. Cowelnecks. Turtlenecks. V-necks. Izods. Tenniswear.

“I don’t know where we’re going to put all of this in this tiny room,” Mrs. Ford harrumphed at one point.

“You can put some in my closet,” I kindly offered, since I had taken up only five measly hangers.

By the end of the hour, all of the closets and drawers were filled, but discomfort still took up most of the space.

Alissa looked so spooked at the prospect of living with me that I thought she might repack right then and there and follow her parents out the door. Instead, she stepped outside to bid her parents a tearful farewell. As they closed the door behind them, I couldn’t help but tiptoe over to hear what they were saying.

I quickly wished I hadn’t.

“It’ll be fine, honey, I’m sure,” I heard Mr. Ford mumble.

“I’m just not sure how I feel about my daughter living with a charity case,” was Mrs. Ford’s haughty reply, before another horrified sob escaped from their daughter.

And so I was marked from day one. A “charity case.”

For the next four years, I searched the campus up and down for anyone, girl or guy, to befriend. The guys wouldn’t give me a second look. They were rich, cultured, clean-cut, athletic and wanted girlfriends who were more feminine versions of themselves. The girls were all Alissa Ford clones, many of them Hillander legacies with family lineages that rivaled the House of Windsor. They treated me like if they got too close they’d catch poverty or, worse, unpopularity. They were confident, preppy, catty, and intimidating. It was an entire school of Ellen Cutters and Liz Alexanders. Even the less thin, less rich, less popular girls wouldn’t associate with me for fear of becoming even more unpopular.

They had a million nicknames for me. “Blue light special” referred to my Kmart wardrobe; they called me “Daisy Mae,” because of my southern twang; and when I dumbly, naively shared details of my upbringing, they started to call me “that Amish girl.”

I tried my best to change and fit in. There wasn’t all that much I could do about my wardrobe, but my hair took up a good amount of time. I went into town one day and got a cheap cut from the local barber school. I wanted graceful “wings” like the other girls in school. “Layer it like this,” I told the student, insecure with her scissors, while showing her a picture of Jaclyn Smith. I ended up looking more like Patti Smith. Then a week later, I tried to fix it with a perm that could only look good on a poodle.

I bought cheap make-up at Woolworth’s: pale pink lipstick, shocking coral rouge, fire-engine-red nail polish, midnight black mascara, and eye shadow—robin’s-egg blue, of course. Somehow, it never looked right, either, as much as I tried to copy the Hillander style.

My other attempts at fitting in were just as disastrous. I tried out for the tennis team, but even a fuzzy yellow ball could humiliate me. The rest of the school, it seemed, had been playing since in utero. Instead, I got really into music. On my lonely jaunts into town, I’d pick up a few cool used or remaindered albums at a dingy old record shop where I liked to kill time with the old hippie who ran it.

And I had a job at the library, which not only was great for extra cash, but it was where I’d always run into my secret crush: Walter Pennington III, a tall, handsome, and extraordinarily down-to-earth member of a high-profile political family. Walt had thick brown hair; a square jaw; and hallow, thoughtful eyes. But I fell for him because he had a layer of depth that no one else at Hillander seemed to have.

Walt was constantly checking out books, but not the usual guy books like Lord of the Rings, or anything by Robert Heinlein or Ernest Hemingway. He preferred reading the modern dramas of Eugene O’Neill, Tennessee Williams, and Edward Albee. But his absolute hero was Sam Shepard.

“They say he’s going to win a Pulitzer this year,” I said shyly one day when he checked out a copy of Angel City and Other Plays. Suddenly, Walter Pennington III, who never before noticed my existence, was talking to me.

Nearly every day he hung around the checkout desk and we discussed plays like “Buried Child,” and “Cowboy Mouth.” “He’s just so quintessentially American,” Walter said fiercely. “There’s something at the core of his work that speaks to the tragic American psyche.”

Soon he was recommending other plays and playwrights for me to read. And when he’d return, he’d be genuinely interested in my opinion. I often fantasized about hopping on the train with him to New York to see an off-Broadway production, then talking about it over espressos in a Village coffeehouse afterward. It was a nice fantasy. And sometimes in reality I thought he might actually be interested in me. There was just one problem with Walter Pennington III.

He was dating my roommate.

I was no competition for blond Alissa and her big boobs; so actually dating Walt would be impossible. But I enjoyed our friendship, glad for Walt’s company when he’d seek me out in the library. And sometimes, if he came by the room and Alissa wasn’t there, he’d look through my record albums and we’d talk about things like what we thought The Ramones’s “Chinese Rock” was all about, or how we thought Marc Bolan from T-Rex was cool. He loved to see which albums I came back with from the town record shop every week; he even borrowed a bunch.

We grew closer, and we’d confide in each other about our dreams. Walt told me that he wanted to be a playwright instead of following the political path his famously widowed mother had planned out for him. “My mom will be crushed, but I just don’t have any interest in politics,” he complained. “I just don’t know how to tell her that I don’t want to major in political science in college.”

It was too good to be true, however. Our friendship came to a crashing halt, thanks to Alissa.

One day in the library, Walt was leaning over the counter reading me a scene from a comedy he was writing. We were sharing a laugh over a clever line when suddenly—thump! Someone tossed a tome onto the counter before me. “Aren’t you supposed to be working? Check this out,” a voice demanded. The voice belonged to Alissa. She turned to Walt. “And what are you doing here? I’ve been looking all over for you.”

“I was just…” His voice trailed off, for he didn’t know what to say.

“Well, I need to finish my Shakespeare paper before tonight, or the whole weekend will be ruined,” she snapped. “And I’d appreciate your help. There’s no way I’m ruining Spring Fling weekend for boring Shakespeare.”

Spring Fling kicked off with a Friday night dance, then a local beach party on Saturday. It was a big annual deal, a sort of pre-prom, and everyone went with a date. I started to get angry, thinking how unfair it was that Alissa would be frolicking in the sand with Walt as I sat in the dorm. I decided to busy myself with returns to put it out of my mind.

“I mean, Jill probably has her paper done, right?” she said just as I turned away. “Right, Jill?”

“Uh, yeah,” I answered. I had finished it a week ago.

“So she doesn’t have any worries this weekend,” Alissa said. “Who are you going to Spring Fling with, anyway?” she asked snidely, knowing full well that no one had invited me.

My silence gave her the answer she sought, and a smug expression replaced the sneer. “Oh, so sorry,” she said, in mock pity. “Maybe next year.” Then she laughed.

“Alissa, that’s not cool,” Walt said meekly before she dragged him out the door.

The next day, Walt abruptly returned all the albums he had borrowed. He never approached me at the library again. And Alissa didn’t speak to me for weeks.

So I should have been suspicious when one night she said to me, “You know tonight is dorm ritual, right?”

I didn’t know what she was talking about. “No,” I said innocently. For a straight-A student, I was so stupid. “What is it?”

“It’s a bonding thing that’s a tradition here,” she said. “The girls do a silly ritual and vow allegiance to the woman named for the dorm so she won’t haunt us during finals.” She added that Lisa, the sophomore who was the R.A. in the dorm and her good friend, was in charge. “All I know is they will knock on our door to get us tonight. And we’re to drop everything and go along.”

“Okay,” I agreed, knowing that not participating would surely earn me grief.

Then at 10 P.M., just as Alissa and I were turning in, the knock came. We followed the other girls down the hall and into the common room, which was pitch-dark, except for the glow of a few candles. Lisa instructed us to sit, spaced out at least an arm’s length in a large circle.

When we were all settled, she began, “This is what you all must do to prove your loyalty to the Agnes Vance dorm at Hillander.”

I held back a yawn, hoping that this stupid ritual would be over soon.

She went on. “I am going to blow out all the candles. Then you must strip down to your underwear. When I say, ‘begin,’ the first girl must take this crown”—she held up a golden cardboard hat from Burger King—“and put it on her head. Then she must stand on one leg, put her hands in a praying position, and say, ‘I, state your name, am honored to be a princess in the court of Agnes Vance.’ Then she must count until five, very slowly, and pass the crown on to the next girl.”

It sounded so idiotic, but harmless, at least.

Or so I thought.

Lisa went around the room and blew out the candles, and the room grew eerily dark. Whispers arose, but she silenced us with a command. “Strip!” she shouted. There was some rustling around the room, and some embarrassed giggles, but silence fell when the first girl began her pledge.

It went on, solemnly, and before I knew it, it was my turn. Alissa, who was next to me, handed me the crown in the dark. I stood up. I balanced on one leg. I placed the crown on my head and put my hands in the praying position. I was doing it all by the letter.

“I, Jill White,” I said, “am honored to be a princess in the court of Agnes Vance.” Then I counted, following the slow pace of the other girls. “One…Two…Three…Four…”

Before I could even say “five,” the lights flicked on. And there I was, standing in the middle of the room, in my bra and undies, wearing a Burger King crown, balancing on one leg and praying. A peal of laughter arose from the rest of the girls, who were all clothed. “I knew she’d be wearing grannies!” I heard someone say.

Then there was the flash of a Polaroid camera. The resulting photo was posted in the cafeteria the next day.

So Alissa had gotten her revenge. And any hope I had of being one of the girls had been dashed once again. I thought things couldn’t possibly get worse.

Then my parents visited. Unannounced.

They were on their way to Rhode Island for—what else?—a Dead show, so they decided to stop in and say hi.

I was in my room, reading, when I heard some giggles outside my door. The next thing I knew there was a knock on the door. I opened it to find my parents standing there, in all their bedraggled, tie-dyed glory.

A year before, I viewed them as my heroes. On that day, they were my bane. I once had thought my father looked like an enchanted woodsman. But seeing him then, his scraggly hair stretching past his shoulders, his unkempt beard sprouting gray, I thought he looked homeless. And Mom appeared pale, tired, and in an untouchable zone of numbness like never before.

Needless to say, I wasn’t all that welcoming. “Why didn’t you call?” I kept asking, over and over. They could have given me a chance to prepare myself. Maybe I could have arranged to meet them off campus. Way off campus.

Dad plopped on Alissa’s bed, putting his bare, dirty feet near her pillow. “Did you put on a little weight, sweetie?” he asked.

I had. Fifteen pounds to be exact. So nice of him to notice.

Then Mom snapped out of her coma and spoke. “What’s happened to your hair?” she asked vaguely. She stepped closer and inspected my face. “Are you wearing make-up?”

That’s when Alissa walked in. When she spied my guests, she was at first stunned—I had never had a guest, ever—then in fear for her life. At least Dad had the good sense to sit up and put his unwashed feet on the floor.

“Aren’t you going to introduce us?” Dad asked, nodding toward Alissa.

I reluctantly, and hastily, made the introductions, as I pulled on my jacket, dying to get out of there.

“Hey, Alissa,” Dad said coolly, just before we were going to leave, “do you know where we might score some good weed?”

Her eyes were full of judgment as she gave a snotty laugh and snapped, “What?” Suddenly, she was above smoking the occasional joint.

“C’mon,” I begged. “I’m starving.” And I finally dragged them out of the discomfort zone known as my room.

I wanted to take my parents into town, but Dad insisted on staying on campus. “How often do we get to come here?” he said.

So much to my misery, we ended up at the small café in the student union.

When we sat, Dad was preoccupied with appraising the students, reading the bulletin board, and getting up to chat with any professor who would walk through. Mom kept eyeing me questioningly.

“Did you get a perm?” she asked. Her earlier tone of disbelief had morphed into simple annoyance.

I nodded.

I knew what she was thinking. I didn’t even ask her if she liked it.

“Just don’t forget who you are, honey, okay?” she said, trying to be understanding, but still sounding very, very annoyed.

How could I ever forget who I was? My classmates were constantly pointing it out.

Like right that very second. A jock from my class, Judd Watson, walked in with his entourage. As he passed my table, he cracked, “Freak alert!” to the hilarity of his cronies.

Mom grabbed my hand and softened. I was glad. I didn’t need her judging me too. “Are you making friends, honey?” she gently asked.

I just shrugged. Her comfort made me want to wipe off my make-up, let my hair go back straight, put on my overalls, hop in their van, and leave Hillander behind for good.

“Jill doesn’t need to be friends with these stiffs,” Dad said. “She’s smarter than them all put together. They’re probably all Republicans anyway.” Dad’s familiar, proud smile took over his face. “Plus, we didn’t send her here to make friends. Your grades with a Hillander education—there will be no stopping you in this world, honey. You’ll leave every one of them in the dust.”

Then I knew—suffering through Hillander’s hellishness would be easier than living with my parents’ disappointment back in Georgia. So I stuck it out. When it came time to choose roommates for the next year, I boldly put in for a single, which sophomores rarely got. But miraculously, mine came through, most likely because every girl in the school doubled up with someone, anyone, so as not to get stuck with me.

So I spent the next three years in the solitary confinement of a single room, every night, every weekend, and every holiday. Yes, even holidays. My parents considered sending me a bus ticket for holidays an outrageous expense. So since they wouldn’t go out of their way to bring me home, I never bothered to save up to buy a ticket myself. And no girl would be caught dead being seen with me, never mind inviting me to her home during breaks. So while most families were carving up a turkey carcass during Thanksgiving, I was sitting in my dorm room. Alone. I would while away many of those hours studying, eating and sometimes I even cut myself.

The cutting started my first year—probably because it was my most traumatizing year, and probably because I wouldn’t ever let Alissa see me cry. My pain and rage had to come out somehow, I guess. The first time I did it was when I came into my room one day to find her reading my journal, ridiculing it out loud to one of her friends. In it, I had written fictional fantasies of how I wanted my life to turn out, what I’d like my “dream guy” to be like, and my opinions on everything. I even made lists, like this one:

Things I want to accomplish in life

1 Skydive

2 Be a good mom

3 Start a charity

4 Start a magazine

5 Travel to all seven continents

6 Fall in love

7 Find a friend

8 Become more likable

I’m proud to say that to date I’ve accomplished #4, #6, #7, and #1, not very long ago for a feature story in Jill. The list is etched in my mind still, as are the emotions I felt when I heard Alissa’s mockery and peals of laughter. It brought back the agony of every social rejection I had withstood at Hillander in one moment.

Alissa was so focused on making fun of my journal that she hadn’t even seen me standing in the doorway. Before she could spot me, I crept back out of the room, so furious and upset that I locked myself in a bathroom stall. I remember sitting there numbly just waiting for the tears. But they wouldn’t come.

Then I noticed a shard of metal sticking out from the broken toilet paper dispenser. I wiggled the metal back and forth, back and forth, until it snapped off. I ran my fingers over its edge, cutting my forefinger slightly, and watched intensely as the blood trickled down my hand. Strangely, it felt good. It felt cathartic. It was a relief.

Pathetic, I know. But it was the only way at the time that I would become distracted from the pain of being an outcast. As often as four nights a week, I’d hole up in the bathroom, now using a Swiss Army knife instead of the shard of metal, and cut—not enough to make the blood gush, though. No, I became an expert. I had practiced just the right touch. Just enough to make it hurt. Just enough to forget the real pain in my life.

I was bright enough to know that it was stupid. And I tried my best to taper off with other distractions, like music—and magazines.

When it was slow in the library, I’d pore over the glossies and mock them in my imagination. As I flipped through each page, examining each zitless face, each rail-thin frame, each blindingly white smile, I’d feel a well of disgust flood my soul. First, because I really resented not being anything like the models. But mostly, I was disgusted because I cared.

And I’d get angry looking at the flawless clothing. The perfectly applied make-up. The “dream guys,” who were all Ken doll doppelgangers. I’d take the bogus quizzes, laugh at the puffy celeb profiles, and make note of the lameness of the advice from the “expert” columnists.

Then one night, in a frenzy of boredom, I started to describe what I hated about these magazines, and what I’d be interested in reading about. One sample entry:

The latest Seventeen came in today. Why oh why do I subject myself to its inane, evil pages? Why do all these rags keep telling people how to be better? What if there were a magazine that just let girls feel okay about themselves? What if there were stories about useful things, like how to live with someone you loathe?

Knowing now that Alissa was reading my journal, no matter where I hid it, I started to write to her directly, planting items that would infuriate her.

Girls can be so phony. I was in the bathroom today when I heard Alissa’s best friend, Tracy Fisher, talking with Alexandra Hunt. Tracy was saying how she couldn’t believe Walt would date someone like Alissa, that they were totally wrong for each other, and that Alissa was looking fat lately, too. I mean, even though it is true—she has put on a few pounds—that’s nothing that a good friend should say, right? I think I’m better off not having any friends here…

I smugly snickered inside when Alissa had a huge fight with Tracy a few days later, and they stopped talking altogether. And I felt a terrific sense of satisfaction noticing her eyeing her figure, and frantically weighing herself, from that day forward.

That’s when I realized how dense Alissa was. She never figured out that I knew she read my journal, even when I out and out addressed her.

I remember writing this another time:

Remember my name, Alissa Ford, because one day, when you’re fading into a life of country club obscurity as nothing more than a proper prop for an uninterested husband, you’ll read it somewhere and wonder how the girl you pegged as such a loser could somehow come out on top.

I wonder if she now remembers that passage as clearly as I do.