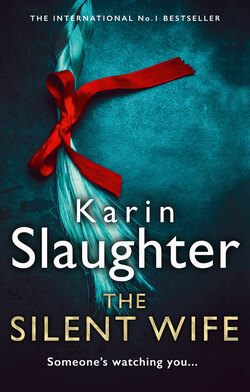

Читать книгу The Silent Wife - Karin Slaughter, Karin Slaughter - Страница 11

Grant County—Tuesday 3

ОглавлениеJeffrey Tolliver took a left outside the college and drove up Main Street. He rolled down the window for some fresh air. Cold wind whistled through the car. The staticky patter of the police scanner offered a low undertone. He squinted at the early morning sun. Pete Wayne, the man who owned the diner, tipped his hat as Jeffrey drove by.

Spring was early this year. The dogwoods were already weaving a white curtain across the sidewalks. The women from the garden club had planted flowers in the planters along the road. There was a gazebo display outside the hardware store. A rack of clothes marked CLEARANCE was in front of the dress shop. Even the dark clouds in the distance couldn’t stop the street from looking picture-perfect.

Grant County had not taken its name from Ulysses S., the Northern general who had accepted Lee’s surrender at Appomattox, but Lemuel Pratt Grant, the man who in the late 1800s had extended the railroad from Atlanta, through South Georgia, and to the sea. The new lines had put cities like Heartsdale, Avondale and Madison on the map. The flat fields and rich soil had yielded some of the best corn, cotton and peanuts in the state. Businesses had sprung up to service the booming middle class.

With every boom there was a bust, and the first bust came with the Great Depression. The only way the three cities could survive was to band together. They had combined sanitation, fire services and the police department in order to save money. Economizing had kept them above water until another boom had arrived by way of an army base being erected in Madison. Then came another boom when Avondale was designated a maintenance hub for the Atlanta-Savannah rail line. A few years later, Heartsdale had managed to persuade the state to fund a community college at the end of Main Street.

All of this booming had happened well before Jeffrey’s time, but he was familiar with the political forces that had led to the current bust. He had watched it happen in his own small hometown over in Alabama. The BRAC Commission had closed the army base. Reaganomics trickled down into the railroad industry and the maintenance hub had dried up. Then there were trade deals and seemingly endless wars, then the world economy didn’t just tank, it had bypassed the toilet and gone straight into the sewer. Except for the college, which had evolved into a technological university specializing in agri-business, Heartsdale would’ve followed the same downward trend as every other rural American town.

You could call it either careful planning or dumb luck, but Grant Tech was the lifeblood of the county. The students kept the local businesses alive. The local businesses tolerated the students so long as they paid their bills. As chief of police, Jeffrey’s first directive from the mayor was to keep the school happy if he wanted to keep his job.

He doubted very much the school was going to be happy today. A body had been found in the woods. The girl was young, probably a student, and certainly dead. The officer on scene had told Jeffrey that it looked like an accident. The girl was dressed in running gear. She was lying flat on her back. She had likely stumbled on a tree root and smashed the back of her head against a rock.

This wasn’t the first time a student had died under Jeffrey’s tenure. Over three thousand kids were enrolled at the university. By virtue of statistics, a small number of them would die every year. Some by meningitis or pneumonia, some by suicide or overdose, some—mostly young men—by stupidity.

An accidental death in the woods was tragic, without doubt, but something about this particular death wasn’t sitting right with Jeffrey. He’d been running in that very same forest. He’d even tripped on a tree root more times than he cared to admit. That kind of fall could lead to several different injuries. A wrist fracture if you managed to catch yourself. A broken nose if you didn’t. You might hit your temple or bust up your shoulder if you fell sideways. There were a lot of ways to hurt yourself, but it was very unlikely you would flip around mid-fall and land flat on your back.

He took a sharp turn onto Frying Pan Road, the main artery into a neighborhood colloquially referred to as IHOP, because all of the streets were named after items you would find at an International House of Pancakes. Pancake Place. Belgian Waffle Way. Hashbrown Way.

Jeffrey saw the rolling lights of a police cruiser splashing the southwest corner of Omelet Road. He parked his Town Car at an angle across the street. Spectators stood on their front lawns. The sun was still low in the sky. Some were dressed for work. Some were wearing soiled uniforms from the night shift.

He told Brad Stephens, one of his junior officers, “Roll out the tape to keep these people back.”

“Yes, sir.” Brad excitedly fumbled with his keys to open the trunk. The kid was so new to the job that his mother still ironed his uniforms. He’d spent the last three months writing tickets and cleaning up after traffic accidents. This was Brad’s first case involving a fatality.

Jeffrey took in the scene as he made his way up the street. Older cars and trucks lined the road. IHOP was a working-class neighborhood, but to be frank, it was nicer than the one Jeffrey had grown up in. There were only a few boarded-up windows. The majority of the lawns were tidy. Lightbulbs still glowed in the floodlights. The paint was peeling, but the curtains were clean, and everyone had dutifully lined up their trashcans on the curb for pick-up.

Jeffrey opened the lid on the closest can. The bin was empty.

He spotted his team standing in a wide, open field that ran behind the houses. The forest was just beyond the rise, at least one hundred yards away. Jeffrey stepped out of the street. There wasn’t a sidewalk. He walked through a vacant lot, carefully scanning the ground as he followed a worn path through the grass. Cigarette butts. Beer bottles. Wadded-up pieces of aluminum foil. Jeffrey leaned down for a better look. He caught a whiff of cat urine.

“Chief.” Lena Adams jogged to meet him. The young officer’s blue uniform jacket was so big that it rode up under her chin. Jeffrey made a mental note to look into women’s sizes the next time he ordered uniforms. Lena wasn’t going to complain, but he was embarrassed by the oversight.

He asked, “You were the responding officer?”

“Yes, sir.” She started to read from her notebook. “The nine-one-one call came in from a cell phone at 5:58 a.m. I was dispatched at that time and arrived at this location at 6:02. The caller met me in the middle of the field at 6:03. Officer Brad Stephens arrived to assist at 6:04. Truong then took us to the location. I verified the victim was deceased at 6:08. I assessed the position of the body and noted a large, blood-covered rock by the victim’s head. I called Detective Wallace at 6:09. We then taped off the area around the body and awaited Frank’s arrival at 6:22.”

Frank had called Jeffrey en route. He already knew the details, but he nodded for Lena to continue. The only way you learned how to do something was to do something.

Lena read, “Victim is a white female between the ages of eighteen and twenty-five, dressed in red running shorts and a navy-blue T-shirt with a Grant Tech logo. She was found by another student, Leslie Truong, age twenty-two. Truong walks this path four-to-five times a week. She goes to the lake to do tai chi. Truong didn’t know the victim, but she was pretty upset all the same. I offered to radio a car to drive her to the campus nurse. She said she wanted to walk it off, take some time to think. She struck me as the woo-woo type.”

Jeffrey’s jaw had tightened. “You let her walk back to campus on her own?”

“Yes, Chief. She was going to see the nurse. I made her promise she’d—”

“That’s at least a twenty-minute hike, Lena. All by herself.”

“She said she wanted—”

“Stop.” Jeffrey worked to maintain an even tone. Most of policing was learning through mistakes. “Don’t do that again. We turn over witnesses to family or friends. We don’t send them on a two-mile hike.”

“But, she—”

Jeffrey shook his head, but now wasn’t the time to lecture Lena about compassion. “I want to talk to Truong before the day is out. Even if she didn’t know the victim, what she saw was traumatic. She needs to know that someone is in charge and looking out for people.”

Lena gave a perfunctory nod.

Jeffrey gave up. “When you got here, the victim was lying on her back?”

“Yes, sir.” Lena thumbed to the back of her notebook. She had made a crude drawing of the body in relation to a stand of trees. “The rock was to the right of her head. Her chin was turned slightly to the left. The ground was undisturbed. She didn’t turn over. She landed on her back and hit her head.”

“We’ll let the coroner make that determination.” He pointed to the foil. “Someone was smoking meth recently. Junkies are creatures of habit. I want you to pull all the incident reports for the last three months and see if we can match a name to the foil.”

Lena had her pen out, but she wasn’t writing.

He said, “It’s garbage pick-up day. Make sure we talk to the crew. I want to know if they saw anything suspicious.”

Lena looked back toward the street, then at the forest. “The victim tripped, Chief. Her head hit a giant rock. There’s blood all over it. Why do we need witnesses?”

“Were you there when it happened? Is that exactly what you saw?”

Lena had no immediate answer. Jeffrey started walking across the field. Lena had to jog to keep up with him. She had been on the force for three and a half years, but she was smart and most of the time, she listened, so he went out of his way to teach her.

He said, “I want you to remember this, because it’s important. This young woman has a family. She’s got parents, siblings, friends. We are going to have to tell them that she’s dead. They need to know we did a thorough job investigating the cause of her death. You treat every case as a homicide until you know it’s not.”

Lena’s pen was finally moving. She was transcribing every word. He saw her underline homicide twice. “I’ll check the incident reports and follow up on the garbage truck.”

“What’s the victim’s name?”

“She didn’t have ID, but Matt’s at the college asking around.”

“Good.” Of the detectives on the force, Matt Hogan was the most compassionate. There were some solid men on patrol, too. Jeffrey had gotten lucky with most of the legacy hires. Only a few were dead weight, and they would be gone by the end of the year. After four years of proving he could do this job, Jeffrey felt he had earned the benefit of tossing the bad apples.

“Chief.” Frank stood in the middle of the field. He was twenty years Jeffrey’s senior with the physical presence of an asthmatic walrus. Frank had passed on the job of chief when the position had opened. He wasn’t one for politics, and he knew his limitations. Jeffrey was certain the detective had his back so long as it related to the job. He wasn’t so sure about the other areas of his life.

“Brock—” Frank coughed around the cigarette in his mouth. “Brock just got here. He’s on his way to the body. She’s that-a-way, about two hundred feet over the hill.”

Dan Brock was the county coroner. His full-time job was at the funeral home. Jeffrey had found him to be competent, but Brock’s father had dropped dead of a heart attack two days ago. The senior Brock had been found at the bottom of the stairs, which hadn’t surprised Jeffrey. The man was a closet drinker. He’d reeked of alcohol.

Jeffrey asked, “Do you think Brock’s up to this?”

“He’s still torn up, poor fella. He was real close to his daddy.” For unknown reasons, Frank started grinning. “I think we’ll be okay.”

Jeffrey turned to see the reason behind Frank’s glee.

Sara Linton was walking through the vacant lot. She was wearing dark sunglasses. Her auburn hair was pulled back into a ponytail. She was dressed in a white long-sleeved shirt and matching short skirt.

“Oh great,” Lena mumbled. “Tennis Barbie to the rescue.”

Jeffrey gave Lena a look of warning. Around the time of his divorce, he’d made the mistake of complaining about Sara in front of Lena. She had taken carte blanche on the insults since then.

He told her, “Make sure Brock isn’t lost in the woods. Tell him Sara is here.”

Lena reluctantly trotted off.

Frank stubbed his cigarette out on his shoe as Sara walked across the field.

Jeffrey allowed himself the pleasure of watching her. Objectively, she was beautiful. Her legs were long and lean. She had a certain grace to her movements. She was the smartest woman he had ever met in a long line of incredibly intelligent women. After their divorce, he had persuaded himself that she hated him. Only recently had he realized that what Sara felt for him was worse than hate. She was deeply disappointed.

On a good day, Jeffrey could admit that he was disappointed, too.

Frank said, “I could punch you in the nuts for the rest of my life and it still wouldn’t be punishment enough for what you did.”

“Thanks, buddy.” Jeffrey patted Frank’s shoulder in a non-appreciative way. Sara’s family was as entrenched in the community as the university. Frank played cards with her father. His wife volunteered with Sara’s mother. Jeffrey could’ve decapitated the high school mascot and gotten less grief.

“Good to see ya, sweetpea.” Frank let Sara kiss his cheek. “Did you just get back from Atlanta?”

“I decided to stay the night. Hi.” Sara spun the last word like a volley into Jeffrey’s face. “Mama told me about the body. She thought Brock might need help.”

Jeffrey was mindful that Frank was not giving them any privacy. He was also mindful that it was Tuesday morning. Sara would normally be getting ready for work right now. “It’s a little early for tennis.”

“I played yesterday. This way?” She didn’t wait for an answer. She followed the trail into the forest.

Frank walked shoulder-to-shoulder with Jeffrey. “Sara just drove down from Atlanta, but she’s wearing the same clothes she was wearing yesterday. I wonder what that means?”

Jeffrey tasted metal from the fillings in his teeth.

Frank called to Sara, “How’s Parker doing? Did you go up in his plane again?”

The metal turned to blood.

Sara hadn’t answered, so Frank told Jeffrey, “Parker used to be a Navy fighter pilot. Real Top Gun type. He’s a lawyer now. Drives a Maserati. Eddie told me all about him.”

Jeffrey could imagine Sara’s father merrily relaying the information over a hand of cards, secure in the knowledge that Frank would do his part to poke Jeffrey with the details.

Frank laughed again. Then he coughed because his lungs were full of tar.

Jeffrey tried to put them all back on a serious footing. They were walking toward a dead young woman. He looked at his watch. He talked to Sara’s back. “The victim was found half an hour ago. Lena took the call.”

Sara didn’t turn around, but her ponytail bobbed as she nodded her head. Jeffrey told himself that it was good to have her here. She’d held the job of coroner before Brock, and unlike the funeral director, she was a medical doctor. An expert’s opinion on the victim was exactly what this case called for. There was no one Jeffrey trusted more than Sara. That the feeling was not mutual was a fact that had lately started to wear on him.

At least a year had passed since she’d filed for divorce. Jeffrey had thought Sara’s anger would eventually burn itself out, but it had taken on the aspects of an eternal flame. Intellectually, he understood why she couldn’t let it go. It was bad enough that he was a cheating asshole, but he had humiliated her in the process. Sara had literally caught him with his pants down, in their bed, in their house, with another woman. Any normal wife would’ve been pissed off. It’s what Sara had done next that was terrifying.

Jeffrey had screamed for her to wait, but Sara didn’t wait. He had wrapped a blanket around his waist as he’d chased her through the house. On her way out, she’d grabbed the baseball bat that he kept by the front door. Jeffrey was stumbling down the front porch when she swung back the Louisville Slugger. She was standing over his 1968 Ford Mustang. The sound that came out of his mouth was like a howl.

But Sara hadn’t destroyed his car. She had tossed the bat to the ground. She had walked over to her Honda Accord. Instead of driving away, she reached through the open window, released the hand brake, pushed the gear into neutral, then let the car roll into the lake.

Jeffrey was so shocked that he’d dropped the blanket.

The very next day, Sara had hired a divorce lawyer, bought a convertible BMW Z4, and tendered her resignation as county coroner. Clem Waters, the mayor, had called Jeffrey and read him the letter. One sentence long, no further explanation, but the entire town knew about the affair by then, and Clem had given Jeffrey an earful.

Then Jeffrey had gotten another earful from Marla Simms, the police station secretary.

Then Pete Wayne had given him a third earful when Jeffrey had dropped by the diner for lunch.

Not to be outdone, Jeb McGuire, the town pharmacist, had barely spoken to him when he’d filled Jeffrey’s blood pressure medication.

Cathy Linton, Sara’s churchgoing, God-fearing, self-righteous saint of a mother, had flipped him off with both hands in the parking lot.

By the time Jeffrey had settled into his dank room at the Kudzu Arms outside of Avondale, he was happy for the silence. Then he’d drunk a lot of Scotch, watched a lot of mindless television, and slowly come to the realization that all of this was his own fault. The way he saw it, his failure wasn’t so much the screwing around as the getting caught. Jeffrey had grown up in a small town. He should’ve realized that, by cheating on Sara, he was also blowing up his relationship with the entire county.

Frank gave another rattled cough as they walked deeper into the forest. The tone was appropriately somber now. The air had turned cold. Shadows tossed back and forth across the ground. In the distance, Jeffrey saw the yellow police tape wrapped around the trees. Lena had cordoned off a wide circle around the body.

Sara’s foot slipped on a rock. Jeffrey reached out, steadying her at the small of her back. He thought about how this would’ve played out a year ago. Sara would’ve reached behind and squeezed his hand. Or smiled at him. Or done anything other than what she did now, which was to make a point of pulling away.

Frank coughed harder as they traversed the hill. They stopped at the yellow tape. The victim lay about fifteen feet away. The girl was slim, maybe five-six, one hundred twenty pounds. Eyes closed. Lips slightly parted. Dark brown hair. Dressed for running. The rock by her head was half-buried in the ground, about the size of a football. Dark blood webbed across the surface. A trickle of blood had dribbled out of her right nostril. No visible marks on her wrists or ankles. No visible signs of bruising, but she had likely been dead for less than an hour. Bruises took a while to make themselves known.

Jeffrey was about to ask Lena to verify again that she hadn’t turned over the body when he heard sobbing.

He turned around. Dan Brock was slumped against a tree. His hands covered his face. His body shook with grief.

“Brock.” Sara rushed to him. She had taken off her sunglasses. Her eyes had dark circles underneath. Top Gun better not get used to late nights. “I’m so sorry about your daddy.”

Brock wiped away his tears. He looked embarrassed, but only because Jeffrey and Frank were watching. “I don’t know what’s gotten into me. I’m so sorry.”

“Dan, please don’t feel the need to apologize. I can’t imagine what you’re going through.” Sara pulled a tissue out from her sleeve. She had always had a soft spot for Brock. The man’s life had not been easy. He was very strange. He’d grown up in a funeral home. All through school, Sara had been the only kid who would sit with him at the lunch table.

Brock blew his nose. He gave Jeffrey a contrite look.

“Sara’s right, Brock. It’s normal to be upset at a time like this.” Jeffrey came from a family of drunks. He should be more sympathetic. “We’ll take care of the scene. Go be with your mama.”

Brock’s Adam’s apple bobbed as he tried to squeeze out some words. He settled on a nod before leaving.

“Jeesh,” Lena breathed out.

Jeffrey shut her up with a look. She was too young to understand what it meant to lose somebody. Unfortunately, sympathy had to be learned the hard way.

“Okay, let’s get this over with before the rain comes.” Sara reached into the supply kit Brock had left. Specimen tubes. Evidence bags. Nikon camera. Sony Camcorder. Lights. She pulled on a pair of exam gloves. “The victim was found half an hour ago?”

Jeffrey raised up the yellow crime scene tape so Sara could cross under. He relayed the information Frank had given him on the phone. “A student called it in. Leslie Truong. She was heading to the lake. She heard music playing from the victim’s headphones.”

Sara noted the headphones, which were on the ground by the victim’s head. They were corded to a pink iPod shuffle that was clipped to the hem of the girl’s shirt. She asked Lena, “Did you turn off the music?”

Lena tilted up her chin by way of a yes. Jeffrey wanted to shake her by the collar. Lena must’ve picked up on his disapproval, because she said, “I didn’t want the battery to run down in case there was something important on it.”

Sara’s eyes found Jeffrey’s with a big, fat seriously?

She had never liked Lena. What Jeffrey viewed as youthful ignorance that could be trained away, Sara interpreted as a willful arrogance that would become a lifelong affliction.

The problem with Sara Linton was that she had never made a stupid mistake. Her high school years had not been riddled with drunken parties. In college, she had never woken up beside a frat boy in a hookah shell necklace whose name she couldn’t recall. She had always known what she wanted to do with her life. She’d graduated from high school a year ahead of time. She had completed her undergrad in three years and still earned a double-major. Then she’d graduated third in her class at Emory Medical School. Instead of taking a high-powered surgical fellowship in Atlanta, she had moved back to Grant County to serve as a pediatrician to the perpetually underfunded, rural community.

No wonder the entire county despised him.

Sara asked Lena, “She was found exactly like this? On her back?”

Lena nodded. “I took pictures with my BlackBerry.”

Sara said, “Download and print them out as soon as you’re back at the station.”

Jeffrey nodded his agreement. Lena wasn’t going to take orders from Sara. Which was a problem for another time.

He told Sara, “The way she fell doesn’t make sense.”

He caught a flash in her eyes. She was too decent to disagree with him in front of his team.

Jeffrey asked a leading question. “Can you explain how she’d fall face-up?”

Sara looked back at the tree root sticking out of the ground. There was a deep furrow in the dirt that matched the dirty tip of the victim’s left sneaker. “The etiologies of falls are well documented. They’re the second greatest cause of unintentional injury behind auto accidents. So, this is classified as a Same Level Fall, or SLF. TBIs—traumatic brain injuries—appear in twenty-five percent of all SLFs. Roughly thirty percent of victims experience what’s called an uncontrollable shift—so by degrees, you’d get a spiral fracture in the wrist, or a hip fracture, or a TBI. Ten percent of victims rotate one-eighty. The center of gravity falls outside the supporting area of the trunk and feet. Damage is due to absorbed energy at the time of impact, so kinetic energy equals body mass and speed, which is related to the height of the fall.”

Jeffrey nodded thoughtfully, more for the expert goat-roping than a fundamental understanding of what Sara had said. He tried, “Her left foot stopped, her body kept moving forward, she spun around mid-air and slammed the back of her head into the rock.”

“Possibly.” Sara knelt down by the body. She pressed open the girl’s eyelids. Then she rested the back of her hand on the girl’s forehead.

This seemed odd to Jeffrey, the kind of old-wives’ tale that led mothers to think they could tell if their kids had a fever. Sara was extremely scientific, sometimes to a fault. If she wanted to check for a fever, she used a thermometer.

She asked Lena, “You were first at the scene?”

Lena nodded.

Sara pressed her fingers to the side of the girl’s neck. Her expression went from concern to shock to anger. Jeffrey was about to ask what was wrong when Sara pressed her ear to the girl’s chest.

He heard a faint clicking noise.

Jeffrey’s first thought was that an insect or small animal was responsible. Then he realized the sound was coming from the victim’s mouth.

Click. Click. Click.

The noise slowly tapered off into silence.

“She stopped breathing.” Sara jumped into action. Up on her knees. Hands pressed against the victim’s chest. Fingers interlocked. Elbows locked as she started compressions.

Jeffrey felt panic stab into his brain. “She’s alive?”

“Call an ambulance!” Sara yelled. Her words jolted everyone into action.

“Shit!” Frank had his phone out. “Shit-shit-shit.”

Sara told Lena, “Get the defibrillator!”

Lena scrambled under the yellow tape.

Jeffrey dropped to his knees. He tilted back the girl’s head. He looked into the mouth to make sure the airway was clear. He waited for Sara’s signal, took a breath, then exhaled into the girl’s mouth.

Most of the air came back into his own mouth. He checked the throat again, making sure nothing was lodged in the back.

Sara asked, “Is air getting through?”

“Not much.”

“Keep going.” Sara resumed compressions, counting out each rapid push. He could hear her panting from the effort as she tried to manually pump blood through the girl’s heart.

“Ambulance is eight minutes out,” Frank said, “I’ll go down and flag it.”

Sara finished counting, “Thirty.”

Jeffrey gave two more short breaths. It was like blowing through a straw. Air was going through, but not enough.

“Half an hour,” Sara said, starting another round of CPR. “Lena didn’t think to check for a fucking pulse?”

She wasn’t expecting an answer, and he couldn’t give one. Jeffrey waited for Sara’s count to hit thirty, then leaned over and breathed out as hard as he could.

Without warning, vomit spewed up into his mouth. The girl’s head jerked forward, smashing into his face with a hard crack.

Jeffrey reeled back. He saw stars. His nose throbbed. He blinked. There was blood in his eyes. Blood on his face. In his mouth. He tried to spit it out.

Sara started slapping the front of his pants. He didn’t know what the hell she was doing until she pulled the Swiss army knife out of his front pocket.

“I can’t clear her airway.” Sara flicked open the blade, telling Jeffrey, “Keep her head still.”

Jeffrey shook off the dizziness. He braced his hands on either side of the girl’s head. Her skin was no longer pasty white, but purple-ish blue. Her lips were turning the color of the ocean.

Sara found her mark, then opened a small, horizontal incision along the base of the girl’s neck. Blood seeped out. She was performing a field tracheostomy, bypassing the blockage in the throat.

Jeffrey took a ballpoint pen out of his pocket. He unscrewed the barrel and got rid of the ink cartridge. The hollow plastic bottom of the pen would act as a tube for the girl to breathe through.

“Shit,” Sara hissed. “There’s—I don’t know what this is.”

She used her thumbs to make the skin gape around the incision. The fresh blood gave way to a grainy mass packed inside her esophagus. Jeffrey could see streaks of blue among the red, almost like the girl had swallowed dye.

“I’ll have to bypass the blockage.” Sara ripped open the girl’s thin T-shirt. The sports bra was too thick to tear, so she sawed at it with the serrated blade until she could rip the material the rest of the way open.

Jeffrey watched Sara’s fingers press into the top of the sternum, just below the tracheotomy incision. She counted down the first few ribs the same way she had counted off compressions. The girl was so thin that Jeffrey could see the outline of the bones under her skin.

Sara pressed the thumb of her left hand just below the clavicle. She layered the heel of her right hand over it, then pushed down with all of her weight.

Her arms started to shake. Her knees came off the ground.

Jeffrey heard a sharp crack.

Then Sara did the same thing again, but lower.

Another sharp crack.

“That was the first and second rib,” Sara told him. “We have to work fast. I’m going to dislocate the manubriosternal joint with the knife. I’ll have to lift the manubrium and push down on the sternum. Then I need you to use the top part of the pen to carefully move the vein and artery out of the way. I can access the trachea between the cartilage rings.”

Jeffrey couldn’t follow the instructions. “Just tell me when to do it.”

Sara pushed back her shirtsleeves. She wiped the sweat out of her eyes. Her hands remained steady. She used the small, sharp blade on the knife to make a four-inch vertical incision down from the previous one.

Dark blood welled over the edges of the opening. His stomach recoiled at the bright white of bone inside the body. The sternum was flat and smooth, maybe half an inch thick, about the size and shape of an ice scraper. Jeffrey had a football player’s understanding of anatomy. He knew all the bad places to get hit. The breastbone had three sections, the stubby top, the long middle and a short tail-like bit that stuck out at the bottom. The bones were all joined together, but with enough force, they could be broken apart.

If Jeffrey was right, Sara was going to pry up the stubby top of the sternum like the lid on a soup can.

She flicked open the serrated blade. “Hold her down. I’m going to score along the joint to make it easier to dislocate.”

Jeffrey pressed his hands into the girl’s shoulders.

Sara was on her knees again. She sawed back and forth across the bone the same way you would carve at the joint of a turkey leg.

Jeffrey bit the inside of his cheek. The taste of blood made him feel dizzy again.

“Jeff?” Sara’s tone warned him to keep his shit together.

He gripped the girl’s shoulders as Sara hacked back and forth. The victim was so small. Everything about her seemed fragile. He could feel her body jerk with each rough cut of the blade.

“Tighter.”

That was all the warning Sara gave him.

She jammed the blade underneath the junction of the joint.

His teeth gave an involuntary chatter at the scraping sound.

Again, Sara used the weight of her body. The heel of her right hand pushed down against the body of the sternum. Her left hand fisted around the knife handle as she pulled up, trying to lift the bone with the serrated blade.

Sara’s shoulders started to shake again.

Nothing opened like the lid on a soup can. It was more like stabbing the knife into the lid and trying to break open the can by force.

Sara told him, “Pull up and press down on my hands.”

Jeffrey covered her hands with his own. He leaned forward, tentative, afraid he would crush the girl.

“Harder.”

He pressed and pulled harder, though every muscle in his body told him not to. The girl was so slight. She was barely more than a teenager. Breaking her open went against every part of Jeffrey that was a man.

“More,” Sara ordered. Sweat dripped down from the tip of her nose. He could feel her shoulders shaking into his hands. “Harder, Jeffrey. She’s going to die if we don’t get air into her lungs.”

He pushed his weight downward and pulled up as hard as he could. The blade started to bend, but Jeffrey realized that the blade wasn’t giving. The bone was.

The joint cracked like an oyster shell.

He tried not to vomit again. The splintering sensation had reverberated up his arms and into his teeth. Worse was the sucking sound of cartilage breaking, sinew tearing, tendons separating, as the bone was wrenched away from the joint.

“Here.” Sara pointed into the open incision. “This is the vein. This is the artery. You need to use the top of the pen so your hand isn’t in the way.”

He could see the vein and artery stringing in front of the ringed trachea like two pink straws. One of them had little red things attached to it. The other looked slick. He couldn’t get the tremble out of his fingers as he used the pen to gently press the vein and artery out of the way.

“Hold still.” Sara held the plastic barrel of the pen between her thumb and fingers. Her elbow was tight to her body. She moved downward, pushing the silver tip of the barrel into the trachea until the bottom third of the pen was inside.

“Move.”

He carefully lifted away his hand. The vein and artery slid back over.

Sara took a breath. She sealed her lips around the pen barrel and exhaled a stream of air directly into the trachea.

Nothing happened.

Sara took another breath. She exhaled through the pen.

They both strained forward to listen, hearing birds chirping and leaves rustling and then finally, after what felt like an eternity, the whistle of air pushing out of the barrel.

The girl’s chest shuddered as it rose to take in a breath. The resulting fall was slow, almost imperceptible. Jeffrey held his own breath, counting off the seconds until the chest rose again and she filled her own lungs with air.

He breathed with the girl, in and out, as the blue drained from her face and life came back into her body.

Sara peeled off the bloody exam gloves. She stroked back the girl’s hair, whispering, “You’re okay now, sweetheart. Just keep breathing. You’re okay.”

Jeffrey didn’t know if Sara was talking to the victim or to herself. Her hands had started to tremble. Tears welled into her eyes.

Jeffrey reached out to steady her.

Sara recoiled, and he had never felt so monstrous, so worthless, in his entire life.

His let his hands fall uselessly back to the ground.

All he could do was wait with her in silence until the ambulance arrived.