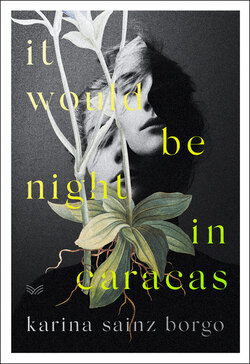

Читать книгу It Would Be Night in Caracas - Karina Sainz Borgo - Страница 14

ОглавлениеIN THE MIDST of that night’s shoot-out, I realized my neighbor’s flush hadn’t sounded. I hadn’t seen Aurora Peralta since my mother went into palliative care. I was surprised to realize I hadn’t heard the irritating pull of the chain, which night after night sounded through my bedroom wall, interrupting my dreams with its gurgle of wastewater.

I knew very little about Aurora. Only that she was timid and dowdy, and that everyone called her “the Spanish woman’s daughter.” Her mother, Julia, was a Galician who ran a small eatery in La Candelaria, the area in Caracas with the largest concentration of bars run by Spanish immigrants. They were frequented by immigrants from Galicia and the Canary Islands, and by the odd Italian.

Almost all the customers were men. They went there to drink bottles of beer, which they sipped unenthusiastically. Even in the hellish heat, they pecked at chickpea-and-spinach stew, lentils with chorizo, or tripe and rice. Casa Peralta was known as the best place in the city to eat mussel-and-white-bean stew. Judging by the number of diners, that was a fair assessment.

Julia, the owner, had been one of the many Spanish women who made a living from the trades they plied before coming to Venezuela: cooking, dressmaking, farming, waitressing, nursing. Yet, most started out working as housekeepers for the local bourgeoisie in the fifties and sixties; others opened small stores and other businesses. They had only one thing to live by: their hands. Spanish printers, booksellers, and some teachers came to the city too and became part of our lives, bringing with them those resounding, lisped z’s that cut through the air in any conversation until they made our pronunciation their own.

Aurora Peralta, like her mother, made a living by cooking for others. For quite some time both before and after Julia’s death, she ran the family restaurant. Then she sold it to start up a pastry-making business that she ran from home. Renting premises was expensive, and it was risky: anyone could stage a holdup and take everything she had, not to mention shoot the unfortunate person who at that moment had access to the cash register.

Only nine years separated us, but she already seemed like an old lady. She came over a few times with a cake just out of the oven. Like her mother when she was alive, she seemed affable and generous. And one thing in her life resembled my own: she had no father. Or at least that was the conclusion I came to when I noticed that the life she and her mother led looked a lot like ours. They started and ended each day together, as mother and daughter. I’d been surprised when she hadn’t come to my mother’s wake. I’d told her in person how poorly my mother was when she’d asked after her health. I assumed the shortages of flour, eggs, and sugar had put a strain on her business, that she was going through a tough time, or had returned to Spain, if she still had family there. Then I forgot about her as easily as I forgot about a faulty lightbulb. I was too busy completing a second gestation, nourished only by my mother, whose presence I could still feel around me. I didn’t need or want anything else. No one would take care of me, and I wouldn’t take care of anyone. If things got worse, I would earn my right to live by walking all over the rights of others. It was them or me. There was no one alive in that country who was generous enough to give me a coup de grâce. No one would blindfold me or put a cigarette in my mouth. No one would pity me when my time came.