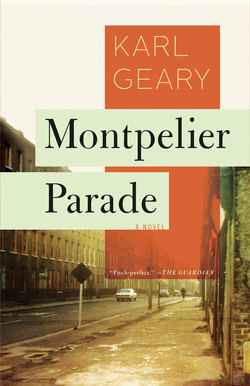

Читать книгу Montpelier Parade - Karl Geary - Страница 12

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление6

It was cold, cold enough to see your breath every time you exhaled. The rain had held off, but your feet had got wet running through the grass, and you pushed your damp socks around with your big toes.

“Excuse me, miss?” you say. You were standing about twenty feet back from the lit off-licence. You were careful not to step toward her; she was alone, heavyset, her face kind. She was carrying a bag, canvas and weighing enough to pull her body to the left as she walked. She wore a fitted peacoat, but the effect was pointless. It made you feel sorry for her, and you hated that.

“Excuse me, miss?” you say again, and this time she slowed, keeping a distance. She was wary of you. You had your coins already in your hand, two eighty, the exact amount. You held the coins where she could see them, so that she didn’t think you were begging or going to hit her.

“I’m really sorry to bother you,” you say in your best accent. “But I’ve been invited to a party tonight.” She stopped a few feet from you then, on the off-license side, where the lights were brightest. “It’s just they won’t let me in unless I bring something—I wonder if you’d mind getting me a bottle of wine . . . in there. It’s two eighty.” You raised your hand and stepped toward her, but not too much. If you could get the money into their hands, they rarely gave it back.

She looked at your hand and then over her shoulder toward the light.

“Thanks very much, thank you,” you say, as if it had been agreed, and took another step toward her.

“Sorry, no,” she says, and pulled the strap of her canvas bag higher on her shoulder, resting her hand across it. “No, no,” she says, and you could see her eyes searching for a way around you, so you stepped back, bowing your head to her.

It was getting late. You wanted to go and find Sharon up at Cats’ Den and still leave enough time to get into town on the bus. You’d sit upstairs, at the back, that was the best. You’d watch them all drinking and kissing and shouting. “Tickets now, folks, tickets now, please.” Then the leafy Booterstown and Ballsbridge would give way to Dublin City, and you’d have your bottle hidden and your single cigarette safe inside your top pocket.

Another fifteen—or was it twenty—minutes had passed. Your shoulders began to buckle with the cold. Two more failed attempts and now fewer and fewer people. You saw a group of five approach, and out of growing desperation you tried it.

“Sorry, excuse me,” you say, and your own voice sounded hollow to you. Two men, taller than you, and three women. You had timed it all wrong, and although one of the men saw you, he wasn’t willing to give up his impending punch line. After they laughed freely, you asked again. They were closer then; they slowed, and their eyes surrounded you. You held the money forward, but already you knew it was no use.

“Sorry to bother you,” you say, “but I’ve been invited to a dinner party.” The blond girl took to laugh. “And it’s just that I wanted to bring a bottle of wine with me . . . as a sort of thank-you.” The coins felt damp in your hand, and you thought of your father doling them out in pieces. You thought of his way with her: Yes, ma’am. No, ma’am. Three bags full, ma’am.

“What is that?” one man says.

“Two pound eighty,” you say. “It’s how much it costs.”

“Two pounds eighty? Two pounds eighty?” He screamed in a fit of laughter; the rest followed. One of the girls pushed at his shoulder affectionately. “Oh, don’t be so mean,” she says, and as she pulled his arm and they walked on, she says it again. “That’s probably the same little wanker that stole your coat,” he says.

It was a long spell, with only a few passing. When they did, they were all wrong or you were afraid of them. You began to dread standing there to watch the shutters roll down, and then you’d have to walk home, too afraid to go into town without the wine for comfort.

A woman walked toward you wearing a tan rain mac with a thick belt pulled across her waist. You could tell she was posh by her tall walk. Her boots made a pop-pop sound. You looked away. You didn’t want her to feel you waiting for her. Pop-pop-pop. When it felt right, you turned.

“Excuse me, miss?” you say, but recognized it was her. Froze then and surrendered everything except her.

“Hello,” she says, as simple as that, and then she waited for you to tell her why you’d stopped her, but you couldn’t. She was smiling at you. She looked over her shoulder and could see the brightly lit off-licence.

“Oh, dear.” She put her hand to her face, and her index finger brushed just above her upper lip. “Where are your friends?” she says, and looked across the empty streets. “When I was your age, I always was the one picked to ask someone too.”

“Hiding,” you say, and you no longer felt as shy now that you weren’t alone.

“Go on, let’s have it then,” she says.

You took the warm coins from your pocket and felt your face break into a smile, until you saw how you had been gripping the coins so tight that they’d left an ugly imprint. You saw the dirt on your nails and felt so grubby that you pitied her having to touch them.

“No, no,” she says. “I want the pitch, the full pitch, and it’d better be good.”

“The pitch?” You lowered your head so she didn’t see how you thought of her.

“Come on.”

“Excuse me, miss?” you say.

“Yes, young man.”

“I’m sorry to bother you . . .”

“The apology is a nice touch, but look up—you’re looking shifty.”

“Sorry to bother you, miss, but I’ve been invited to a party, and I wanted to bring a bottle of wine, you know, as a thank-you.” You held out your hand as you had before. “They won’t serve me inside, and I wondered if you’d mind . . . Thank you, thank you so much.” You were a little pleased with yourself; you couldn’t help it because she seemed a little pleased.

She stood still, watching you a moment. “Good,” she says, and turned and walked directly to the shop, not taking the money, but calling over her shoulder, “Red or white?”

“Red.”

“Good choice,” she says before disappearing behind the door.

You were no longer cold but stamped your feet anyway. An old woman passed, heavy with bags, and you thought maybe you would have helped her if you weren’t waiting. As you looked around, you felt warm to it all. The worried faces that drifted endlessly by in cars, hands cuffed to the wheel. The Monkstown church, lit up in the distance, suddenly seemed a kind building even though they were Protestant and just showing off having floodlights.

When she came back, her rain mac was open, and you could picture her inside the shop, carelessly opening the button between her thumb and forefinger. She held the bottle, wrapped in a dark plastic bag, against the same red jumper she had on earlier.

“You know one of us should be ashamed of ourselves,” she says. She was wearing the same skirt, but you had gotten that wrong, it was darker than you remembered, the wool heavier. “Here, and hide the bloody thing or we’ll both be done.” She was a little out of breath.

“Thank you,” you say.

“You’re welcome. I hope she is very lovely, your friend waiting up the street.” She began to button her coat. “Red wine is romantic.”

“Romantic?”

“Well, are you and the boys going to split a bottle of wine?”

“No,” you say, and smiled because that was true.

“Well, have a good night,” she says, and she seemed for a second almost shy. She smiled a little and touched your arm before she walked away.

“Thank you,” you say, and held the bottle like a trophy and watched until she disappeared.