Читать книгу Emily Carr - Kate Braid - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление1

Meeting D’Sonoqua

The Indian People and their art touched me deeply.

– Emily Carr, Growing Pains

It had rained all day: a grey, ceaseless downpour under heavy skies. All day she had waited for the Indian agent who promised to take her to the remote village where local people told her she would find totem poles. She had been travelling for days – by coastal freighter, fishboat, launch, or canoe – however she could reach the next small village, the next pole. She was going to sketch them before they all disappeared, as she feared, forever.

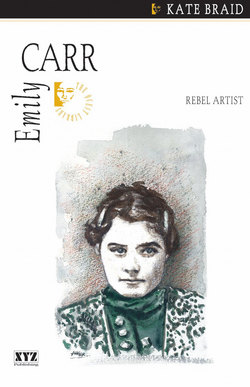

Emily Carr’s painting of D’Sonoqua, wild woman of the

woods. It was the first time Carr met this supernatural

figure, towering above stinging nettles in the abandoned

village of Gwa’yasdams in northern British Columbia.

And so she waited, in the mission or perhaps in some native cabin, while the Indian agent went about his business, took his time, almost forgetting about the lone white woman whose luggage consisted mostly of a sketch sack, a blanket roll, and a dog for company.

Finally, he was ready. The woman lifted her few belongings to her shoulders, called in a soft English accent to the young native girl who would accompany her on the site, and the three of them climbed into his open boat. When they arrived at the deserted village of Gwa’yasdams, it was dusk. The woman and child stood on shore and stared up at the frightening tall figures of totem poles, which leaned forward as if to touch the visitors.

“There is not a soul here. I will come back for you in two days,” the Indian agent said, and left them alone. As his boat rounded the shoulder of the bay and disappeared, the little girl burst into tears. “I’m ’fraid,” she said.

The woman led the way up a narrow path overgrown with stinging nettles. It was dark when they reached the empty mission house. As the door creaked open, they heard the scamper of rats. The woman tried to make them comfortable by building a fire, perhaps to cook some food, but the firewood was wet and she couldn’t make the stove work. She had no candles, so they ate her canned food in darkness, then laid their blankets on the floor and slept.

The next morning the air was a curtain of dampness. When the woman followed the plank walk, she had to cut through stinging nettles that reached over her head. Her thick clothes and long skirt and stockings protected her a little, but nettles bit at her face and hands. Slime from thick yellow slugs coated the wet wood under her feet. Suddenly, with a cry, she fell. When Emily Carr looked up, an immense wooden figure loomed over her.

The creature had been carved from a huge red cedar tree. She was so tall, the nettles barely reached her knees. Her long arms stretched wide as if about to grab someone. But it was her face that seized Emily’s attention.

Her eyes were two dark sockets outlined in dazzling white under fierce, black eyebrows. Emily felt as if at any minute the cry of the tree’s heart might fly out from the protruding lips that framed her open mouth. At the ends of two black hands, the figure’s fingertips were painted ghostly white. Round ears jutted from her head as if to miss nothing, and rain and mist put a slick gloss on the red of her body, arms, and thighs.

Emily pushed through to the bluff so she could look back and see all of the creature. She sketched, and watched, for a long, long time – until a thick mist moved in off the sea and the figure disappeared.

“Who is that image?” she asked the little native girl. She could see the child knew what she was speaking of, but the girl said, “Which image?”

“The terrible one, out there on the bluff.”

“I dunno,” the girl lied.

All that night, as the child slept, Emily sat at the open window of the mission house and listened to the foreign sounds outside their thin shelter: the cries of an abandoned dog, the crash of breakers, and the groaning, living sounds of huge trees around her. She was 1

Five years earlier, on a trip to Alaska in 1907 with her sister, Emily Carr had been deeply impressed by the totem poles she saw. She loved their monumental size and majesty. She was already a serious artist who had studied in San Francisco and London, and now, when she did some sketches on the spot, an American artist who spent every summer in Sitka told her he wished he had done them because they had “the true Indian flavour.” His praise got her thinking.

In trying to convert the First Nations peoples to Christianity, missionaries, with the co-operation of national governments, had virtually condemned traditional native culture. They declared all symbols and tools of traditional native life – masks, rattles, ceremonial regalia, and the totem poles, as well as important festivals such as the potlatch – “pagan.” The native population was already plummeting, decimated by diseases introduced by contact with white people – smallpox, tuberculosis, and alcoholism among them. Many of the native people who survived were now moving to larger centres for all or part of the year so they could get jobs at white people’s canneries and mission stations. As the villages emptied, their totem poles were being cut down, burned, or sold to museums and to rich tourists as “souvenirs.” Others were simply rotting naturally.

Emily Carr had probably never seen standing totem poles in their natural setting until she went to Alaska. On Vancouver Island she was familiar with the Coast Salish and Nootka (now Nuu-chah–nulth) people, but they were not carvers in the same tradition as the northern Tlingit whose work she now so admired. She certainly didn’t understand the meaning of these monumental carvings in the same way native peoples did. She didn’t understand, for example, that their rotting in place was considered a natural part of their cycle. As a non-native, deeply Christian woman born into the perspectives of her time, she couldn’t appreciate the full importance of the standing poles in affirming lineage, rights, and privileges within the communities that raised them. But she was one of the very first Europeans to see past the deep racial bias of her time to admire the skill of native carvers and the power that shone out of their work. She knew the poles were an important part of cultural identity here in the northwest – and she knew they were rapidly disappearing.

As the ship carried her back to Victoria, Emily made a decision: she would document the totem poles of British Columbia. She would make as accurate a record as she could, of as many poles as she could find in the entire vastness of the province. It would be her way of preserving them, at least on canvas; it would be her mission.

And, true to her promise, over the next twenty years she made eight trips to the northwest and Interior of B.C., to the northern coast of Vancouver Island, and to the Queen Charlotte Islands – now known as Haida Gwaii – seeking totem poles. Later she would come to paint other things, including the forest itself, but for now, her focus was all on the totem poles in northern native villages.

For a single white woman in the remotest parts of B.C. in the early 1900s, alone except for her dog and sometimes a native companion or guide, it was an extraordinary odyssey. She rode on trains, steamers, wagons, fishing boats, and canoes. She stayed in tents, roadmakers’ tool sheds, missions, and in native people’s homes. Sometimes she asked a boat owner to leave her alone in a deserted village for days at a time, all so she could fulfil her promise to herself to preserve the power and beauty of the totem pole.

The poles appealed to Emily’s love of spirit, to her love of the truth – the art – revealed by going to the heart of things. She appreciated how, without lies or hypocrisy, the First Nations carver caught what seemed to her the inner intensity of his subject, by going even to the point of distortion so the spirit expressed in the carving gained strength and power.

Sketching the poles, spending long periods of time alone in the forest, taught Emily Carr many things, but always, that fierce female totem pole figure with its deep black eyes and shouting mouth seemed especially to talk to her.

They met again, years later, in a small village where Emily had come to sketch totem poles. The traditional large community houses of native villages were slowly falling down and being replaced by smaller buildings. On this day, Emily walked inside the frame of one old building in which the huge centre beam had fallen and rotted away. But one of the carved figures that had supported the beam still stood.

Emily knew instantly who it was by the figure’s jutting ears, wide-open eyes, and calling mouth. Her carved body was dried and cracked by the sun. In some ways she was even more terrifying, for her two hands gripped the mouths of two upside-down human heads, and the sun cast deep hollows around the angles of her face.

When Emily asked her native guide, “Who is she?” he was slow to answer, as if he resented this intrusion of a white woman into matters entirely Indian. Finally he answered, “D’Sonoqua.” He pronounced it in a way Emily’s tongue could not follow.

“Who is D’Sonoqua?”

“She is the wild woman of the woods.”

“What does she do?”

“She steals children.”

“To eat them?”

“No, she carries them to her caves.” And he pointed across the water to a purple scar on the mountain’s side. “When she cries, ’oo-oo-oo-oeo’,” he said, “Indian mothers are too frightened to move. They stand like trees, and the children go with D’Sonoqua.”

“Then she is bad?”

“Sometimes bad … sometimes good,” and he walked away, as if he had already said too much.

As Emily understood her, D’Sonoqua was a supernatural being. Again she stared for a long time, sketching, watching. Finally, as she turned away, two things caught her eye. One was a small bird building its nest in D’Sonoqua’s round mouth. The other was the soft shape of a tabby cat, sleeping unafraid at D’Sonoqua’s feet.

Later, as Emily waited for the little boat that would come (she hoped) to pick her up and take her to the next small village, she mused, “I do not believe in supernatural beings. Still – who understands the mysteries behind the forest? What would one do if one did meet a supernatural being?” And then, “Half of me wished that I could meet her, and half of me hoped I would not.”

Many years later she would meet D’Sonoqua, the wild woman of the woods, one last time.

Emily Carr (lower right) about age sixteen, with her sisters

(from centre front, clockwise) Alice, Lizzie, Edith, and Clara.

Emily always felt like the black sheep of her family.

1 . Paula Blanchard, The Life of Emily Carr, Vancouver/Toronto: Douglas & McIntyre & Seattle: The University of Washington Press, 1998, p. 129.