Читать книгу Office at Night - Kate Bernheimer - Страница 7

ОглавлениеHe has suddenly realized the window is open. He can feel it. But how far open? And who opened it? Chelikowsky. His grandfather owned a brewery. Came to the new country with a handful of hops in his pocket. Died of a pulmonary embolism at the age of forty-nine. Left his son, Chelikowsky’s father, on the Lower East Side with a cart and donkey and two hundred pounds of plums he couldn’t unload. Debts. So he went north and west, all the way to Hell’s Kitchen, did the father, who died even younger, with even less, and now Chelikowsky, failed painter, failing businessman, with his own office, is hoping to make it to fifty, and maybe celebrate a little, only someone has opened the window and he doesn’t know who. The new girl? Couldn’t be. The window weighs a thousand pounds in the summer, when the wood swells. He’s strong, Chelikowsky, a wiry ox, and he can barely budge it. Sneak a glance over at her? He can feel her looking at him, always looking. Maybe she’s got secret muscles. Some of them do. Once he went out walking up Ninth Avenue with a girl who accepted the one kiss he gave her, then knocked him out cold when he attempted a second. He sneaks a glance. So quick you can’t see it. So quick he sees nothing. Just a girl-shaped blur.

He loves his office. Has an apartment on Thirty-Eighth he can barely stand to set foot in. Somehow inherited a cat from a friend’s cousin that uses a two-foot dead space behind a wall in the kitchen as its toilet. The cat doesn’t have a name. He would never bring it here. Jesus H. Christ no way would he let that cat into this office. Even if it is cute. A cutesy cat. He doesn’t even like cats. He thinks maybe they make him sneeze. Once he threw his cat across the room. Just picked it up and threw it. Then felt bad, sure, but not that bad, because before it got to the other side of the room, he had run over and caught it.

He is speedy, is Chelikowsky. In high school he could run well under eleven seconds in the hundred-yard dash. Is someone trying to kill him? That’s the question that is preying on his mind. Not ten minutes ago he picked me up and used me to call his mother and came very close to telling her. Telling her that he thought someone might be trying to kill him. What would happen if he stood, turned, shut the window? he thinks. Is it even open? He tries one of his quick glances. Again so fast you can’t see it happen. He is expecting a client. Over the phone, over me, the case sounded interesting. But complicated. Like a Chinese puzzle. He hates those. There is a guy down on the corner who sells them. Five cents a pop. Make your fingers hurt and your head explode. Why are they always complicated, his cases? he wonders. Chelikowsky used that word, complicate, when he hired her, this new girl. He simply can’t bring her name to mind.

I’m a mind-reading telephone. Nifty, right? Lots of us can read minds. I mean lots of what’s in this room. See things. Know things. Why wouldn’t we? Look around you. There, wherever you are. Imagine what’s reading your mind. What’s not?

He used to have a wife, did Chelikowsky. Gladys. He has known three other guys with ex-wives named Gladys. His Gladys had loved gladiolas. It was a joke between them. In the early, giddy, gaudy days. In the summer, he put on short pants and a boater and took her to the boardwalk at Coney Island. Now Gladys is gone, even long gone.

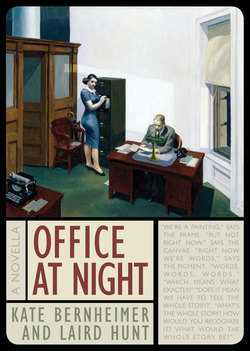

Anyway, sometimes Chelikowsky sleeps here. Turns off the desk light, leans back in his chair, lets the night glide by. Chelikowsky did two years at Hunter, studied English, was still painting. His mother’s pride for two years. Then, boom, done. His mother has seen this office. She says she doesn’t like the chair right next to the door. Says it’s too close to the filing cabinet. Says it is too red. Says the desks are too red and too close together. “It’s not decent to be sitting alone in an office with a girl,” she says. She says she doesn’t like typewriters either. They frighten her. But me she likes. She has used me often enough. Still, sometimes she will meet him at the lunch counter across the street. This is where she says all these things about his office to him. He takes it, the good with the bad. She is his mother, after all. He had whooping cough that turned into pneumonia when he was a boy. She didn’t sleep for two weeks. Caring for him. His mother. They both drink their coffee black.

“My cases are often complicated—you o.k. with complicated?” Chelikoswky asked the girl when he hired her. He can feel her eyes on him. She’s in the filing cabinet too much. It’s like a mania. Some kind of condition. Granted, he asked her to make a dent in his paperwork. The last girl left it a mess. She used it to store her toothbrush. He found it, along with an empty tin of Colgate tooth powder, filed under M. Why under M? Her name was Janice. Janice Jones. He called her JJ. Sometimes he would follow her. He would leave a little after she did and trail along behind her. He wasn’t very good at it. She just did things like buy a pork chop and some milk then get on the subway. He was pretty sure she knew he was following her, though she never let on. Then one night he turned around and saw that she was following him. She was holding her little bag from the butcher’s and wearing a grin. Good old JJ.

They tried it on once and it didn’t work out so well, because he was already tight when they started. JJ quit working for him to get married to some other guy. And because he, Chelikowsky, was “kind of a crumb.” According to her. Though it was true that after they tried it on and it didn’t work so well, he shoved her out the door. Just a little shove. Placed his palm into the handsome concavity between her shoulder blades and good-bye. He never shoved Gladys. Even if he had thrown and caught a cat. He would never shove Marge. Marge is her name. Chelikowsky smiles. Even though you could never tell. Marge, Marge, Marge, Marge, Marge.

Is it Marge who wants to kill me? Chelikowsky wonders. She has just handed him a document, plucked from the cabinet and dated two years ago. She didn’t say a word—just strode over and plopped it onto the desk in front of him. He has read it twice and can’t make heads or tails. “Dear Abraham Chelikowsky” it starts. “May we meet next week at Madison Square? I will trust that you recall my situation so recently and gravidly discussed between us. I will wear the same hat as I did in the old days. Yours most sincerely and diffidently . . .” It is unsigned, bien sur. Who the fuck? It rings no bells. What does “gravidly” mean? A case? He was about to ask Marge why she handed him this two-year-old cryptogram when he noticed the window was open. Wide. Like a mouth. I don’t want to die, thinks Abraham Chelikowsky.

And now I must stop because in just a moment I will start to ring.

I should shut that window, Marge Quinn thinks. And perhaps I will in a minute, although it always sticks and I’ll have to ask Miss Chan for help. I have asked her for help, Marge Quinn thinks, six and a half times already today, and I don’t like the idea of asking her again. It’s just that the trucks stop at the corner below and the exhaust smell is awful and Abraham gets so awfully grumpy when the window is open. Even, Marge Quinn thinks, when he has opened it himself. Or mostly opened it himself. Miss Chan always helps him. She has such a skill with windows, thinks Marge Quinn.

Marge Quinn of the wide, soft fingers. Marge, whose father arrived in this fine city confined in the hold of the boat. Because of a transgression during the passage. He has the same fingers. He was always gentle, was her father, except when he was killing someone. But that was long ago, Marge Quinn thinks. In the old country. Here he spends his days in a chair by the window of their fourth-floor tenement walk-up. Here he sleeps quietly and doesn’t yell. All the money she doesn’t need goes to him. He has always been so gentle. Except that once she walked in on him killing someone. Long ago. Where she was born. But she was born here, she thinks. So how could that have been?

There is a coconut product that she favors for her fingers. She told Miss Chan about it just the other day and for a moment Miss Chan seemed interested, then looked away. But not before clicking her tongue. Quietly, but Marge Quinn heard it. It makes her feel very tired to think of Miss Chan clicking her tongue. She clicks it frequently. Like she is breaking matchsticks. Abraham must hear it. All those matchsticks. Though he never shows any sign. Such a gentleman, thinks Marge Quinn. She of the soft fingers. So much softer than the fingers of Janice Jones. Always jamming them here and jamming them there. Good riddance, I say, when that one left. Miss Chan’s fingers are fine. Nothing special. Just regular fingers. And they don’t move too fast. But the fingers of Marge Quinn! Like firm butter in five little bags.

She loves to file. Put more in than she takes out. I suspect one day, if Miss Chan lets her, she will fill me up, and they will have to buy another cabinet, and perhaps I will finally have a friend. A true friend of my own kind! I would love to be full. And not with tooth powder. Not with tooth powder or wrapping paper or sandwich leavings. There is still a little oil in my upper drawer, back left. Oil! Marge Quinn fills me with firm paper and firmer card stock. She is a treasure, truly.

Abraham, Abraham, thinks Marge Quinn. Abraham, who fired her predecessor Janice Jones. She left him a letter, did Janice Jones, thinks Marge Quinn. She filed it under Q. The letter begins, “I am not fired, you crumb I could have maybe ever-so-slightly loved but never quite did, because I quit.” The letter is not typed. It contains a number of vague threats. She filed it under Q and Marge Quinn just found it. With her soft fingers. She does not pluck. She coaxes. So gently. And handed it to him. To Abraham, as she calls him. When she thinks no one is listening. Abraham, Abraham, Abraham. Of course Miss Chan has heard her. She hears everything. Sometimes when she is just walking past, she gives me a good pat on the side.

Marge Quinn handed “Abraham” the letter from Janice Jones, only when she handed it to him her soft fingers, having pulled out more than one letter, nothing to be ashamed of, let fall the one she wanted him to read. So that he could take steps. Forewarned is forearmed! Her lovely, long, soft fingers let fall the one that would help him to take steps and handed him something else, some old letter from a client he has forgotten all about. She has just seen the letter on the floor. There it is, oh darn it, darn it! she thinks. I know if I reach for it Miss Chan will ask me what I am doing, she thinks. Bending down like I would have to beside Abraham’s desk. And she is so efficient, Miss Chan, that she will have it anyway before I have finished my bend. Only there it lies, the letter from Janice Jones that says, “I told them all what you did to me. All the things you did to me.” Only he couldn’t have done anything. Dear Abraham. She calls Chelikowsky that, does Marge Quinn of the long, buttery, soft, slightly clumsy fingers, whose father once killed people, even though she has only worked in the office for, what, two weeks?

Here is the story, lit with my finest glowing light, of the letter Chelikowsky is holding. It, the letter, was written by an individual of curious intent, whose concern—though Chelikowsky himself was ultimately unable to see it and so missed an opportunity to profit—cut to the core of our great (if modest) company’s central mission. The letter Chelikowsky is holding is the second he received from this particular correspondent. The first was much longer. So perhaps this is the story of a letter Chelikowsky once held. That he once held and then forgot. Regardless, he was a widower, the writer of these letters, a Mr. Stetly, who lived in a palatial apartment on Fifty-Sixth Street with only a single servant, a “cadaverous” individual named Gibson, whose gender was never specified. These two had for some years, before Mr. Stetly entered into contact with Chelikowsky and Co., spent their days cataloguing what was purported to be a vast collection of unusually masterful forgeries. Stetly, an artist of no particular note in his youth, one who had quickly wrung the towel of his own talent dry, came into possession of an absolutely unlooked-for and monstrously significant tinned oyster fortune when he was in his early thirties, and immediately set about acquiring Impressionist masterpieces.

Stetly’s taste was excellent, but his eye was poor, and after three years of profligate buying from a Paris-based dealer named Delors, he learned at the vernissage of his one and only exhibition that every single one of the paintings he had poured so much of his fortune into was fake. Stetly’s high-strung wife, who had never liked the Impressionists and would die some short time later from an imperfectly swallowed chicken bone, smelled disaster to come, smacked Stetly hard on each cheek, then flung herself out the nearest window. Her fall was broken by the accommodating arms of an oak tree that grew too near their luxurious brownstone, and as Stetly, “buoyed by the audacity of her gesture,” helped nurse her back to health over the coming weeks, he formulated a plan that, properly implemented, would allow him to tack into the erratic winds of fortune. When Stetly told his wife—whose name was Gladys by the by, although Chelikowsky, distracted as usual, skimmed that part of the very long first letter Stetly sent him and so missed this—what his plan was, she demanded ten thousand dollars, the deed to their Long Island property, and a statement of separation, then left him to sink his ship on his own.

Undeterred, Stetly began implementing his plan, which, far from seeing him end his relationship with Delors, saw him doubling down on it, so that in the years that followed he used the lion’s portion of his remaining fortune to buy fake after fake, and not just of French Impressionists. Into his collection went fake baroque landscapes, fake Scandanavian realists, fake American gothic, fake Italian Renaissance, fake Japanese woodblock prints. Somewhere along the line, Stetly forgot the part of his plan where he was to begin reselling the works as first-rate forgeries for a nice profit, and instead kept amassing them, eventually going through Delors’s daughter, who had taken over the family business when her father, as wealthy as Stetly had once been, retired.

One morning, some months before he had taken up pen to write to Chelikowsky and Co. for guidance, Stetly had awoken, “as if from a dream,” to find Gibson, whom he did not remember hiring, dusting away at the stacks and stacks of pictures in their often unusually tawdry frames. He had decided to take an inventory of his collection before having it appraised. Not terribly long into this process, he realized that some of his key works, his earliest fakes, were no longer in his possession. As the weeks passed, more pictures went missing. He was writing Chelikowsky, he said, because of their previous acquaintance, which Chelikowsky couldn’t help but recall, in order to seek his advice on the matter. He did not expound on the nature of the advice he was seeking, nor fully clarify which part of “the matter” he hoped Chelikowsky could address, nor offer anything concrete about the nature of their previous acquaintance, but he did say he would have to apply for a line of credit, one that he would be in a position to terminate as soon as he began selling portions of the collection. Chelikowsky, who is not immune to the seductions of idiosyncratic solicitations, nonetheless set the letter and its request aside. Even though it is quite true that he once knew Stetly and was to some extent in his power. I feel quite certain that he will do the same thing with this second letter too.

I do not light up the room. I am the secretary in this strange little office.