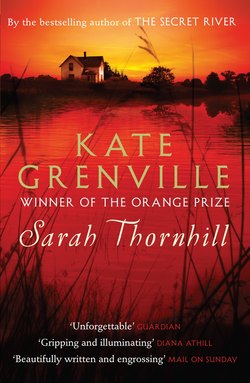

Читать книгу Sarah Thornhill - Kate Grenville - Страница 14

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеTHOSE YEARS split up into the times Will and Jack was away, and the times they was back. Another kind of day and night, only months long. I turned twelve and Jack gave me twelve shells in a box, the whole thing small enough to fit in my palm. Want to marry me, Sarah Thornhill?

I turned thirteen while they was away again. Wondered if he’d bring back another box, thirteen shells this time, but he never brought the same thing twice. That year it was an eggshell, creamy with green specks, that he’d blown out and kept in a box full of feathers. Then they went off again.

It got to be so every trip was longer. The seals running out, Pa said. Had to go further to find them and when they did, not so many as before. Where it might of taken two months to fill the hold, now they might be gone the best part of a year.

By and by I started to get a womanly shape, and my monthlies come. Ma was too genteel to talk about anything that went on in your insides, but Mary was fifteen going on sixteen, had her monthlies for a few years. She was making eyes at Billy Cobb from up the river. He was a lump of a boy and I couldn’t see that Mary liked him much, she was just practising on him. He’d row down from Cobb’s now and then and the two of them would go off by themselves. When I got my monthlies she was kind about it. Not children anymore, we got on better.

You can have babies now, Dolly, she said. That’s what it means.

I must of looked blank.

With a man, you know, she said. You seen how the horses let down that tube thing they’ve got. Get up on the mare if you let them, put it inside. Same with people, only a bit nicer about it.

I’d seen the poor old mares, and the cows too, and I wasn’t going to have anything like that done to me. But I was ready to stop being a child. Had a feeling Mary might not know everything about what men and women did together.

With Will and Jack gone so long it was a dull old time. I’d wake up early but wish I hadn’t, the day stretching out too long. So many people in the house, but empty too. I’d go up to the cave, the way I always had, and sit in the honey-coloured light listening to the What Bird. The bird was the same and the light was the same, but somehow they’d lost their flavour. I wondered at the child I’d been not so long before, who thought a morning answering the What Bird was a morning well spent.

My body was becoming someone else’s, and my self too, but body and self neither settled yet into their shapes. I was out of sorts, waiting to catch up with myself.

Have you got worms, Dolly, Ma said. You’re restless as a cat.

Came at me with the opening medicine. I made myself sit still after that. Commend thy soul to patience, I said to myself, like I’d heard the parson say. Commend thy soul to patience.

Every day and every week much like the last. We’d have the visits from the Langlands and the rest of them, Sophia always on at Pa, when would Will be back? Me and Mary went riding, as far as the rocks where Thornhill’s finished, or down the other way towards Payne’s Mill. Might go with Johnny up out of the valley along the Sydney road as far as Martin’s Corner, he was sweet on Judith Martin, her father had the place there. Once or twice we took the horses across on the punt and up the new road on the other side of the river. Stop at the top and look at the view down over the valley, turn round again.

Never far enough to get anywhere, and back home a few hours later.

A trip to Sydney one time, that was a big thing. I’d just turned fourteen. Down the river on Trevarrow’s Emily, then out to sea for the run down the coast to Port Jackson, lucky to have a fair wind and a calm sea. A public house in Bridge Street wanted a man to train up, and Johnny was nineteen, wanted to do it. Couldn’t wait, he was that keen to get away from old Dead-and-Alive, by which he meant our valley.

I didn’t fancy Sydney, loud and people rude and quick, and the gentry running you down on the street prancing along on their horses. Caught a glimpse of the governor, all gold braid and a cocked hat with a feather, that was exciting for two girls from the Hawkesbury, but a few days later and we was back home and the damn bread and mutton having to be done over and over and the same old dishes washed and put away morning noon and night.

That speckled dog was a smart creature. Didn’t care one way or the other about Dolly Thornhill. But knew that wherever she was, Jack would be there too, sooner or later. If I went to the cave, the dog pushed through the bushes and sat up with me on the sandy floor so I’d feel its warm breath on my ear. If I went down to the jetty it lay on the boards watching down the river the way I was doing, one black ear cocked up.

I’d sit with Pa on the verandah, he let me have the telescope if I didn’t ask too often. Black shiny mangroves, wet rocks, water. You could see every ripple through the glass. If there’d of been a boat you’d of seen all the faces on deck.

Every day that passed was a day I was waiting for Will and Jack to be home.

I was sitting on the front steps one afternoon, the dog nosing up and down the gravel path and Pa behind me on the bench. I was staring out at nothing, wishing but not knowing what I was wishing, when I heard the bench fall over, Pa jumping up so quick.

Will! Will’s home! he shouted.

Pushed past me, took the steps two at a time, out the gate and down the road with that funny crooked run he had and the telescope still in his hand. Didn’t care that the men were staring at Mr Thornhill with his boots flapping from where he hadn’t taken the time to lace them up.

I was halfway down the track after him when the dog ran past and when I got to the jetty it was standing out on the end, straining towards the boat, but it was still way off down the end of the reach. The sail hanging slack from the yard, the people on board no bigger than ants. One of them must be Will. And one of the others would be Jack.

That thought—Jack!—brought something into my throat, as if I’d run too hard. I knew then what I hadn’t known all those months of mooning about. It was Jack I was waiting for.

There was a crowd on the jetty now, Mary and Ma and Bub, all telling each other how long Will and Jack had been gone and how slow they was coming up the reach, and was the tide on the turn or would they have to get out the oars. On and on they went, and the boat not seeming to move.

Give us the glass, Pa, I said. So’s I can see.

The eyepiece full of sky, then bush. I slanted down too fast, missed the boat. Tracked along those blue ripples and there was the old grey wood of Emily, and up on the bow, leaning forward as if to get to us quicker, there he was. Jack. Black hair glistening in the sun, beard so thick it hid most of his face. Looking straight at me. I waved and he waved back, even though I must of been nothing more than a shape with an arm coming out of it.

When Emily got up to us at last, Jack jumped across the last yard of water, didn’t wait for them to tie the boat up. So light on his feet for such a big man. Landed next to me neat as a cat.

Well, he said. It’s Sarah Thornhill, I do believe.

The same as I’d remembered, his eyes crinkled up with smiling.

Dolly Thornhill, stuck for words! That was a new one.

The speckled dog ran in circles with its tail going like a carpet-beater. Pa slapping Will’s shoulders, Will slapping Pa’s, the two of them shouting at each other.

Still want to marry me, Sarah Thornhill? The humour of it was on Jack’s face, he took a breath, his mouth started the words. But then he saw the new shape of me, changed his mind. The words hung between us.

It was nothing. A silence the length of a heartbeat, and Jack’s eyes looking into mine. But it said everything is different now.

When the others walked up to the house the two of us hung back. We’d walked up that track together a hundred times but I’d never had to think before how you walked beside someone. How much space did you leave between you? Did you touch them as you walked, did your hand brush against theirs as it swung backwards and forwards, and how did you breathe?

Pa stoked up the fire in the parlour and splashed out his best madeira into the good glasses. His hand shaking, he was that pleased to see Will back. Anne brought in cake but Pa said, none of that stuff, Anne, these fellers need some of that meat from last night. Pickle with it and plenty on the plate, mind!

I made sure I ended up next to Jack on the sofa. Took a leaf out of Sophia’s book, working it that way as we come into the room, but making it look like chance.

Pa wanted to know everything. How many storms and how many skins, was the first mate any good and did they give you enough victuals. Couldn’t get enough of their tales of hardship, sitting in his cosy parlour with his rich acres round him.

An ember flew from the grate and I put out my foot to snuff it. New boots from Abercrombie’s, buttons up the side, made my feet very small. Took my time with the ember and when I sat back I saw Jack was smiling to himself.

They’d had a dangerous time of it. Not enough seals, so they had to stay too long, past the good season, and the storms caught up with them. Went way down south, some island too far and too cold for anyone to live on. Took the risk rather than come home with the boat half empty.

Hard to find as a damn flea, Will said. Wasn’t it Jack?

But Jack was smiling at the fire, and I was the only one who knew why he wasn’t listening, because my hip was jammed up tight against his and where we touched something was running from his body into mine and from mine into his.

Wake up, Jack! Will said. Good living sending you to sleep!

So you find it? Bub said. Or what?

Found it right enough, Jack said. And these fellers on it, been there three years. Left behind to get the seals, some bugger of a captain forgot to come back for them.

Three years, I said. They’d be dead!

Well and they near was, Jack said. Ever think what a seal might taste like, Sarah Thornhill?

His face very close, I could see how the hairs of his beard sprang away from his red lips.

What does it, Jack, I said. Taste like.

He was watching my mouth, my eyes. His were flecked, green and brown. The eyelashes very black.

Bloody awful! Will shouted from across the room. Rank like fish, that right Jack?

So these fellers, Pa said. No boat to get away?

That’s right, Mr Thornhill, Jack said. No boat, so it was make one or stop there till they died. A few trees on this place, but no saw with them, only an axe.

What, cut the tree down, chip it away to a plank! I said. One plank out of a whole tree!

You’re a quick study, Sarah Thornhill, Jack said. That’s it. One tree, one plank.

God in heaven save us, Pa said.

How many they done when you got there, I said. How far off a boat?

Eight done, Jack said. Long ways off a boat. By God they was pleased to see us.

Kissed us, Will said. Bloody kissed us!

Pooh! Bub said. What, on the mouth?

Get away with you, lad, Pa said. They never.

Reckon you’d find it in yourself, Sarah Thornhill, Jack asked me under everyone laughing. Set in to cut that first tree?

I would, I said. Got a stubborn streak, Jack, and not as dainty as you might think. What I want, I don’t stop till I got it.