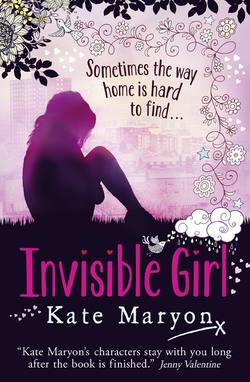

Читать книгу Invisible Girl - Kate Maryon, Kate Maryon - Страница 9

Оглавление

Dad’s been weird since asking Amy to marry him. He’s gone quieter than ever, drifting round the flat like a wisp-thin ghost. Amy’s got louder and bossier, like one of those Salvador Dali paintings from my book, all twisted and unpredictable. She’s spending our money on things for the wedding every single day. She’s bought two dresses already so she can choose. But we’re not allowed to see. She shuts herself in Dad’s room with her friends and they coo over them like they were kittens. She’s bought special silky underwear and these pearly shoes that shimmer. She got Dad this smart grey suit with a pink silk shirt and a purple cravat and he says he feels like a turkey all trussed up for Christmas. I’m more invisible than ever. No one’s speaking to me. They wouldn’t even notice if I never came home.

Amy’s the only important one round here. She’s high up, towering above us like a queen, making up all the rules. And I’m getting so used to being invisible that I’m shocked when Mrs Evans tells me I got an A+ for my still-life art project. She says my painting stands out from the crowd and it’s going on the special display board for Parents’ Evening for everyone to see. Dad won’t see it, because he never bothers with Parents’ Evening, but I run home quick to whisper my news to Blue Bunny.

“Here,” says Amy, shoving an envelope in my hand when I get to the top of the stairs. She’s standing by our front door with her sunglasses propped up on her head. “Take it, quick. I’ve got to go.”

She squints from the sunlight and pulls her mirrored sunglasses down so I can’t see her eyes.

“And take this,” she says, dropping a bulging backpack on the ground in front of me. “We put as much of your stuff in as we could.”

“Amy,” I say. “What are you on about?”

“It’s all in the envelope,” she says. “Your dad’s written everything down. Come on, quick, give me your key to the flat.”

I stare at the white envelope, my name scrawled across the front in Dad’s loopy handwriting. I stare at the fat backpack on the ground.

“Why do you need my key?” I say. “I need it to get in. Come on, Amy, I’m desperate for a wee.” Then it dawns on me.

“Oh, no! Did someone break in again?” I ask. “Did Dad have to change the locks?”

“No, dummy,” says Amy, waggling her hand in front of my face. “Look, Gabriella, I did you a favour waiting for you; you should be grateful. I was worried someone might nick your stuff and then you’d be stranded. Anyway, we need to give your key back to the landlord. Your stupid dad forgot to pay the rent. Stupid fat bum he is!”

My tummy sinks to the ground and a red rage blazes inside me.

“I knew this would happen,” I screech. “It’s all your fault. Dad’s not stupid, he’s just kind. Mum used to trample all over him just like you do and it’s not fair. We were OK before you came along. I told him we mustn’t spend all the money. It’s gone on that stupid wedding stuff you got!”

She tuts and checks her watch.

“Gabriella,” she says, “I’ve had enough of listening to you gabble on about stuff. It’s not important. You’re not important. I tried to be a good mother to you and make your life better, but what thanks do I get, eh? Anyway, you’re not my problem any more.”

I fumble in my bag for the key, my hands fluttering like leaves.

“What are we going to do?” I say. “Where are we going to live?”

“Just be a good girl for once in your tiny life, stop asking questions and give me the key,” she sneers. “Everything’s explained in the letter. But think about it, Gabriella, your dad’s not that kind, is he? He’s known about the eviction for a few weeks now. If he was that much of a kind guy he’d have told you all about it. If he was that nice he’d have been waiting here to give you your bag. He’d have put you on the train and kissed you goodbye himself.”

Her words hit me like a car, spinning me through the air, rocking me sideways. “Wh… what…” I stammer. “What train?”

“I told you,” she says. “I haven’t got time to stand here and explain it all. You’re going on a train to your mum’s and we’re catching a plane to somewhere exotic. Yay!”

She waggles her fingers in my face again, her big fat diamond engagement ring glinting in the sun.

“I’m the lucky one!” she sings. “I always have been and always will be, you’ll see!” Then she turns and runs down the stairs, her sandals clicking and clacking on the concrete.

“And,” she shouts up at me, “don’t get yourself into trouble, Gabriella, OK?”

I lean over the edge of the balcony. “Amy!” I shout. “Where’s Dad? I don’t understand! You can’t just leave me!”

Then a smart car with a taxi sign on top screeches to a halt outside our flat. Dad’s in the back, his face turned away from me. Amy jumps in next to him. Everything’s going in slow motion like it sometimes does in films.

“Dad!” I shout, racing down the stairs, my tummy dangling off strings, twisting and turning in knots. “Dad, what’s going on?”

He doesn’t even look at me; the taxi driver flashes the indicator light and zooms away. I run after them, calling “Dad” over and over, but I can’t catch up and the car disappears round the corner and gets lost in the stream of traffic.

Back up the stairs I pull my phone out of my bag and call him. It goes straight through to answer phone without ringing and so does Amy’s. I know they won’t answer, I know they’ve gone, but I can’t stop pressing the green button over and over and over, my shaky thumbs slipping and sliding on the keys.

“What’s all the racket this time?” says Mrs McKlusky, shuffling along the balcony in her tartan slippers. She stops dead in her tracks and pins me down with her eagle eyes. “What you doing here anyway? Your dad said you was moving. I saw him heaving all your stuff out this morning. He made a right old mess of everything and then upped and left. Nonsense, it is, leaving us to clean up after him.” She clacks her teeth on her tongue. “Utter nonsense.”

My heart flaps inside me, a caged owl with frantic wings.

“I errrrm,” I say, stuffing my phone in my pocket. “I errrrm, I forgot we’d moved, that’s all, Mrs McKlusky. I’m off to meet my dad and Amy now. At our new place. Bye!”

I pick up the backpack and my school bag and quickly scoot back down the stairs. When I get out on to the road I keep my eyes on the ground. I don’t want to see anyone; I don’t want anyone to see me. I don’t want to talk. I just keep walking and walking, clutching the chalk-white envelope in my hand.

And when I’m far away from our flats, far, far away from Mrs McKlusky’s beady spy eyes, I find a bench and sit down. My hands are shaking. My shoulders are aching from the really heavy bags. I stare at the envelope. I stare at Dad’s handwriting scrawled in huge letters across the front. Gabriella.

I trace my finger over the blue biro shapes. He didn’t put a kiss. He didn’t even underline it. I pull out my phone and press the green button again and again and again. I listen over and over to his voice. “Hi, Dave here, I’m off on me hols, so don’t leave a message as I won’t be getting back to you anytime soon… Hi, Dave here, I’m off on me hols, so don’t leave a message as I won’t be getting back to you anytime soon.”

I slip my finger in the envelope and open it a tiny bit. But then panic freezes me; my heart bangs loudly and I stare at Dad’s handwriting for ages. What did Amy mean about going to Mum’s? We don’t even know where she lives, we haven’t heard from her for years. I don’t even want to see her. I don’t want to read the stupid letter. And I’m not going to Mum’s either. No one can make me. They can’t.

I fold the envelope carefully and tuck it away in my bag.

I’m starving. I forgot to take my lunch to school and I need the toilet really badly. I pull my Maths homework out and stare at it to distract myself. The fractions keep swirling on the page and turning into Amy’s words. They make my heart pound in my ears and my face and hands drip with sweat. You’re going on a train to your mum’s! You have to go to your mum’s! To your mum’s!

My eyes are prickly and blurry and I can’t even see the numbers any more because they’re swimming. I squeeze the tears away and stuff the fractions back in my bag. I get out my Geography homework and draw a huge volcano. I make loads of molten red lava gush out the top and spill down the sides. I draw loads of tiny little cars and houses, and miniature stick people running away. I make them all scream, with big howling mouths, like that painting called The Scream in my book. I draw loads of ash smoke billowing everywhere and blinding everyone and I draw a girl on a bench; alone, with all the hot lava and amber sparks whooshing towards her.

My legs are cold. I open the backpack, but it makes my tummy churn so I tug at the nylon straps and click the black buckles shut. If I don’t read the letter and I don’t look in the bag maybe it will all go away. Maybe it’s really a dream and in a minute I’ll go back home and Dad will be sighing on the sofa and Amy will be trying on her new stuff and everything’ll be like normal.

My mum keeps prowling around my brain, lurking like a sharp-toothed shark. And what’s weird is I can see everything from years ago as if it were yesterday, as if I had a TV on replay in my mind. There’s Mum pulling on one arm, screeching, and Dad pulling on the other arm, sobbing, and I’m in the middle and only five. I’m just standing there with a blank face feeling invisible. No one even notices that they’re tearing me in half like paper. And Beckett’s just standing there trembling with his arms hanging long at his sides and his face turned whiter than the moon.

I wanted to go with Beckett so badly. But I couldn’t leave Dad alone, could I? He looked so helpless and Mum made me feel so shaky and panicky inside. And then she spat in Dad’s face and dropped my hand. She grabbed hold of Beckett and pulled him away. I wanted to run after him. I wanted to fly to Beckett. I wanted to hold on so tight and never let him go. And I tried to move my legs, I did, but they wouldn’t move. They couldn’t leave Dad standing there alone, looking so sad.

After I’ve finished colouring in the volcano I start answering the questions.

1: What is the Ring of Fire?

The Ring of Fire is a volcanic chain surrounding the Pacific Ocean.

2: Where are volcanoes located?

Volcanoes are found along destructive plate boundaries, constructive plate boundaries and at hot spots in the earth’s surface.

3:What are lahars and pyroclastic flows?

I know what those big words mean, but I can’t be bothered to write the answer down. My mum’s biting huge chunks out of my brain with her shark’s teeth, blood dripping down her face. My tummy’s grumbling. I try calling Dad again, and Amy. A plane roars overhead and it makes me think about them flying off. Where are they even going?

I pack my stuff up and start walking. I don’t really think about where I’m going, but suddenly I’m standing at Grace’s front door, which is painted smooth red and has a shiny brass lion’s head knocker and letterbox. Yellow flowers nod in wooden boxes on the windowsill and tangles of white roses hang around the doorway like a big messy fringe. I stuff my nose in a creamy bloom and breathe in its perfume. It smells so beautiful. “Hi,” I say, when Grace’s mum opens the door. “Is Grace in?”

“Sorry, love,” she says, “she’s at her dad’s tonight. You’ll see her at school tomorrow.”

“Oh,” I say, hopping from one leg to another. “Sorry, I forgot.”

I stand there like a dummy with my mouth hanging wide open. “Can I quickly use your bathroom, then? I’m desperate.”

Grace’s mum smiles and opens the door wide to let me in. I dump my bags in the hallway, race up the stairs and wee until there’s not even one drop left inside me. I fold the flowery toilet paper round and round my hand and stroke its softness on my cheek. On my way back I peep into Grace’s room and I wish I could slide into her bed and hide. I wish her mum could bring me some dinner up on a tray and puff the pillows so they’re comfy. I wish she could climb in and watch a programme on Grace’s pink telly with me.

“Bye, then,” says Grace’s mum, when I’ve picked up my bags.

I stare at her, a million words racing round my mind, thundering like horses.

“Can I have a biscuit, please?” I say.

Grace’s mum laughs, then she gets the biscuit tin from the kitchen and lets me choose. “Take a couple,” she says, “but don’t go spoiling your tea.”

I take two. My hand lingers in the tin. I should pull it out, I know, but it won’t budge. My tummy’s grinding like a peppermill.

“Oh, go on,” she smiles, “take a handful, but don’t tell your dad!”

She looks at me with these soft friendly eyes. She touches her hand on mine and I wish I could grab it and cling on like the roses round the door. I wish I could say something. I wish I could tell her.

“You OK, Gabriella?” she says. “You look, um…”

“I’m fine,” I say, grabbing more biscuits. “Just starving after Games, that’s all.” I skip down the path very fast, away from her eyes and her questions. “Thanks for the biscuits, thank you, bye!”