Читать книгу Prairie Imperialists - Katharine Bjork - Страница 11

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеChapter 2

Scouting

From St. Paul it took Scott three days to make the trip across Minnesota to Dakota Territory, since the train traveled only during the day. In Fargo he borrowed a boat and spent a couple of days hunting ducks and prairie chickens. From Fargo to Bismarck, where the Great Northern Railroad came to an end, was another day’s journey. Scott found Bismarck, mainly board shanties, to be very crude. He was struck there by the thought that “one might go a thousand miles west or travel north to the Arctic Circle with the probability of not seeing a human being.”1 This was pure fancy on Scott’s part, of course. However remote it might have felt to a young man coming from the East, the region he was entering was not an empty land devoid of people. Quite the contrary, as he was about to discover.

No doubt Scott received some kind of advice and orientation from those he met at each of his stops on his journey west, though there is no record of what this might have been. Perhaps as important as any counsel he received as he journeyed to take up his first army assignment was the influence of a guide who had accompanied him through West Point, and who, even earlier, had interpreted for him the mysteries and majesties of Indian Country. As he would throughout his life, Scott carried with him a favorite work by the man he called “the great historian of the North,” Francis Parkman. For ten thousand miles, wherever he went on the plains he took with him Parkman’s Conspiracy of Pontiac in his pack basket. Even in the Philippines and Cuba, he reread Parkman’s works “with perennial pleasure.” Before he saw the “wild Missouri” with his own eyes, Parkman’s prose had fired his imagination with an image of that mythic river. “Nowhere,” Scott thought, had it been described so fitly and so beautifully as by Francis Parkman.”2 The historian’s descriptions added interest—and meaning—to everything Scott was encountering in the country he had dreamed of since boyhood.

In fact, though born a generation apart, Scott and Parkman had much in common. Both came from genteel East Coast families in which clergymen figured prominently. Boyhood enthusiasm for the strenuous life out of doors led to unusually ambitious hunting expeditions in the remote West. While still young men, both moved in the social circles of leading scholars and scientists of their day. A generation earlier, also in his early twenties, Parkman’s first foray west had taken him through the frontier posts of New York and Pennsylvania where he sought the historical detail, but above all, the authentic atmosphere of wild America with which to color his early works, such as Conspiracy of Pontiac.3

As he waited on the banks of the Missouri for the ferry to carry him across the river so that he could take up his post at Fort Abraham Lincoln, Parkman’s prose had predisposed Scott to see in the landscape before him the primitive America he sought. With Parkman as his literary guide, he had in fact been prepared to arrive at the threshold of wild America with “a spirit attuned to understand it and to rejoice in becoming a part of its life.”4 For Parkman, and no less for Scott, the destinies of this “savage scenery” and the “savage men” who lived there were intertwined, one and the same. And both were doomed. “The Indian is a true child of the forest and the desert,” wrote Parkman, “The wastes and solitude of Nature are his congenial home, his haughty mind is imbued with the spirit of the wilderness, and civilization sits upon him with a blighting power. His unruly mind and untamed spirit are in harmony with the lonely mountains and cataracts, among which he dwells, and primitive America, with her savage men and savage scenery, present to the imagination a boundless world, unmatched in wild sublimity.”5 Besides equipping the younger man with a romantic reading of Indian Country and an epic historical context in which to frame his own experience for the part he would play in its conquest, Parkman served as a kind of guide for Scott in two other important respects as well. His work served as an example of ethnological writing as a way of making sense of the world that mattered to literate men of the East. In addition to conducting his research among the documents he found in French and British archives and even traveling to defeated Richmond in 1865 to take possession of Confederate documents for the Boston Athenaeum, Parkman wrote in a way that conflated the natural historical writing of explorers like Henry Schoolcraft with the literary appeal of writers like Henry Wadsworth Longfellow and James Fenimore Cooper. At the same time, Parkman was perceptive enough to recognize that politics, not just savage nature, played a role in Indian actions, something that was overlooked in most contemporary accounts of Indian life and warfare.

More importantly than the impact of Parkman’s prose on the young man’s imagination, Parkman suggested the rudiments of an ethnographic method that the young Scott admired and could emulate. In his preface to Conspiracy of Pontiac, Parkman explained his methodology (and personal predilection) for obtaining knowledge of “primitive life” through what would later come to be regularized by various ethnographically oriented sciences as participant-observation, in which “knowledge of a more practical kind has been supplied by the indulgence of a strong natural taste, which at various intervals, led me to the wild regions of the north and west. Here, by the camp-fire, or in the canoe, I gained acquaintance with the men and scenery of the wilderness. In 1846 I visited various primitive tribes of the Rocky Mountains, and was, for a time, domesticated in a village of the western Dhcotahh, on the high plains between Mount Laramie and the range of the Medicine Bow.”6 Entering the region whose scenery had been so romantically rendered by Parkman thirty years earlier, Scott, too, sought out opportunities to visit and “domesticate” himself in Indian villages and scout camps as a way of pursuing an interest in the language and customs of the various tribes among whom he lived and campaigned for the next quarter century. The habits of observation he developed on the plains he later employed as military governor of Sulu and also in Cuba and on the border with Mexico. His own observations of native Americans led him to modify Parkman’s essentialist constructions of primitive men to a degree. Scott’s intimacy with Native Americans complicated the proposition that Indians were fundamentally different from white men. From his close contact and dependence on scouts in the field, as well as from his interest in the language and culture of the people of the plains, Scott gradually learned to relate to the Arikaras, Crows, Cheyennes, and others with whom he worked and fought as men, not merely as Indians. With at least one of them, Kiowa Indian Scout Sergeant Iseeo at Fort Sill, Scott formed a friendship as deep, mutual, and enduring as any he made with a white man.7 Throughout a lifetime of interaction with Indians and involvement in Indian affairs, first in the army and later as a member of the Board of Indian Commissioners, however, Scott never changed his belief that Indian cultures represented an earlier stage of civilization and that progress and the Indians’ own best interests required that they change and adopt white ways. Scott applied such an evolutionary schema to assessing stages of development in Cuba and the Philippines as well.8

Crossing the Missouri River downriver from Bismarck, Scott reported to Fort Abraham Lincoln, the headquarters for the Seventh Cavalry, in September 1876. He found his new regiment in the midst of a major reorganization. Survivors of the Bighorn battle had only recently returned to the post. When he reached Fort Lincoln, Second Lieutenant Scott, along with eight other newly arrived junior officers, bedded down on the drawing-room floor of the house that had just been vacated by Elizabeth Custer. Within a short time, five hundred enlisted men and five hundred horses arrived at the post. Many of the new recruits turned out to be “Custer Avengers,” men from the cities who were motivated to sign up by what Scott called the “stress of excitement of the Custer fight.” As a young officer, he struggled with the indiscipline of this “rough lot,” many of whom ended up deserting or being court-martialed.9

Besides preparing for a renewed campaign against the Lakota (Sioux) and Cheyenne in Montana, the soldiers also policed the Great Sioux Reservation on which the Seventh Cavalry was located, sixty miles upriver from the Standing Rock Agency. Their role was to chase and discipline Indians who “broke out” and to prevent them from joining the forces of open resistance to U.S. authority over the country. This work employed the same strategies that became central to the army’s work of pacification in the Philippines and Cuba: concentration and surveillance of populations, strategic alliances to obtain intelligence and allies in war, and an emphasis on disarming those under their jurisdiction and taking away their horses. Some of Scott’s first assignments away from the post were to enforce efforts by the army to confiscate weapons from Indians on the reservation. Fort Abraham Lincoln continued as the base for campaigns after hostile Indians in the West. The army defined as hostile Indians who defied the government’s directive to report to an agency, renounce resistance, and adopt white ways, like farming, on the reservations.

Soon after arriving at Fort Lincoln, Scott determined that his best chance for advancement in the frontier army lay in becoming a commander of Indian scouts. Indian auxiliaries were just as important to the current campaign to contain and disarm Indian resistance to the encroachment of white civilization onto the prairies and mountainous West as they had been in earlier wars of imperial expansion in North America. As in George Washington’s day, the success of American soldiers depended on maintaining strategic alliances with tribes with shared or complementary objectives. Indian scouts provided crucial information that was essential to the success of any campaign in the West: deep cultural knowledge, geographical knowledge, and highly developed observation skills.

The role of scouts in the military changed and gained new prominence following the Civil War, as the army shouldered the mission of policing areas of the trans-Mississippi West and the formerly Mexican domains of the Southwest, where incursions of white settlers threatened not just the vestiges of native self-determination, but Indian survival as well. As the army tried to negotiate the unfamiliar and forbidding terrain and climate of the plains and desert Southwest, as well as the complicated military and diplomatic challenges posed by their frontier missions, they turned for assistance to earlier arrivals in the West, men familiar with the physical and cultural landscape in which they now had to operate. As historian Louis Warren put it, the army needed indigenous scouts because “the soldiers who came to fight the Plains Indians so easily got lost in the strange grasslands.”10

Army officers also needed scouts to serve as intermediaries between the military and Indians—both adversaries and allies. Not surprisingly, some of the most valuable scouts were “half-breeds,” men whose joint European and Indian kinship gave them an advantage in moving between different cultures. Then there were the “squaw men,” white men who had come to the plains as fur traders and hunters and who had married native women. Men such as Will Comstock, Abner “Sharp” Grover, John Y. Nelson, and Ben Clark all spoke one or more indigenous languages.11 Clark, who was married to a Cheyenne woman, had been working as a scout and interpreter for the army for more than a decade when Scott met him in the late 1870s. Scott developed great respect for Clark, who he thought was unequaled among white scouts for his mastery of Plains Sign Language.12 Such scouts also possessed knowledge of Indian social organization and customs that was of strategic value. At the same time, their role as intermediaries between cultures sometimes made them suspect to whites in the army and larger society, who found their transgressions of racial boundaries unsettling and even threatening.13 “Scouts’ intimacy with Indians and the frontier was thus a double-edged sword. It provided the army with keys to white conquest of the savage wilderness, but simultaneously, it implied the danger of race decline, in which the savagery of the frontier essentially conquered the race, turning white men against civilization.”14 A few white men, untainted by mixed-race marriage or ancestry, also served as scouts for the plains army in the 1860s, notably Frank North of Nebraska, who had become fluent in Pawnee while working as a clerk on the reservation and who organized three battalions of Pawnee scouts to fight alongside the army against the Cheyennes and Sioux.15 In the Southwest, Charles B. Gatewood and John Bourke also fit this mold. Without question, the most famous white scout of this period was “Buffalo Bill” Cody. William F. Cody was a Civil War veteran who worked as a civilian scout for the army before launching his successful career as a showman. Cody’s Wild West show presented an epic drama of the conquest of Indian country for audiences in the East—and even in Europe—who were eager consumers of mythic depictions of conquering Indians and settling the frontier.

Legendary figures such as Buffalo Bill notwithstanding, a majority of the scouts who fought with the army in its Indian Wars were other Indians. For the first two hundred years of their involvement in the wars and frontier skirmishes of the Anglo-Americans, native auxiliaries had remained outside the army’s formal organization. By the 1850s a number of men in the army were advocating a more systematic organization of Indian auxiliaries. In 1852 Captain Randolph B. Marcy recommended attaching Delaware scouts and guides to each company of troops on the frontier. Captain George B. McClellan of the First Cavalry went a step further. Sent to Europe in 1855 to report on the Crimean War, he was so impressed by the Cossacks that he endorsed the potential use of “tribes of frontier Indians,” who would serve as “partisan troops fully equal to the Cossacks in both Indian and ‘civilized’ warfare.”16 In 1866 Congress authorized the formal enlistment of scouts. Though it limited Indian service to “the Territories and Indian country,” the Army Reorganization Act incorporated Indians into the structure of the army for the first time. Scouts could enlist for periods ranging from three months to one year. They received the pay and allowance of cavalry soldiers and their duties were determined by the military district commander. The highest rank available to Indians was that of sergeant.17 The same legislation also organized six all-black regiments for deployment in the West, including the Ninth and Tenth Cavalry, more famously known as “Buffalo Soldiers.” Both African American and Indian troops were to be commanded by white officers.18

Indians rendered service to the military as scouts for a number of reasons. Some sought alliances with the expanding power. In return for acting as guides and interpreters and sometimes for fighting, scouts obtained guns and other goods. Their relationship to the army offered opportunities for taking booty from enemies they helped the Americans fight. Horses and other livestock provided a particularly desirable form of compensation for Plains Indians who accompanied the bluecoats into battle. No less importantly, Native people were motivated to join forces with the Americans for diplomatic reasons, in an attempt to stave off destructive wars or otherwise influence the destinies of their people and the other tribes around them. Until the Civil War, however, scouts were attached to, but did not form an integral part of the army. This was generally true of white scouts also, such as William Cody, who always scouted for the army as a civilian.

Besides the possibilities for professional advancement, Scott also relished the autonomy and scope for personal initiative that working with Indians in the army afforded a junior officer. He later compared being a commander of Indian Scouts in the frontier army to being an aviator in the Twenties and Thirties; “one could always be ahead of the command, away from the routine that was irksome, and sure to have a part in all the excitement,” he wrote.19

In his early days with the Seventh Cavalry, Scott chafed at any assignment that threatened to tie him down in camp or involved responsibility for the transportation of heavy equipment or supplies. As he saw it, he had not “undergone five years of toil at West Point to come out to the Plains to be a wagon soldier.” He had “come west to be a flying cavalryman … [not to] travel at a walk behind the column.”20

In the beginning, Scott applied himself to learning the language of the Lakota Sioux, on whose reservation Fort Lincoln was located. He reasoned that since the Lakota were the dominant group on the northern plains, their language would function as a kind of “court language,” like Latin or French. This assumption was reinforced by the fact that the Arikara scouts attached to the regiment all spoke it. He thus began to study the language under their tutelage. He quickly discovered that while the Lakota’s language did not function in this way and was of limited use to him in communicating with other groups, there did exist a lingua franca on the plains: sign language. Scott continued his study of sign language throughout his time on the plains. By the time of his assignment to the Bureau of Ethnology in 1897, he was acknowledged as the white man—in or out of the army—with the most knowledge and expertise in signing.21

On his first expedition away from the fort, Scott was given an assignment to form a battery out of some muzzle-loading guns and some cavalry horses that were no longer fit to ride. His task was to train the horses and men in his troop to move and handle the battery. Scott chafed at this onerous assignment and instead arranged with his friend Lieutenant Luther Hare to take command of the battery along with his own troop while Scott took every opportunity to travel with the Arikira scouts, who broke camp before daylight and rode out in advance of the soldiers, “covering the country far in front as carefully as pointer-dogs in search of quail.”22 Scouting also gave him the opportunity to hunt, which he loved. He attributed his commanders’ continued acquiescence in his absence from the column in part to their appreciation of the loads of prairie chicken, snipe, and ducks he brought back to camp. “The procurement of game made [the Colonel] more willing to let me go ahead with the scouts … and it soon became a matter of course for me to leave the battery with Hare, my superior, in command, and go off with the scouts before daylight every day.”23 He spent as much time as he could in the company of scouts, either riding with them and learning from observation how they operated or pursuing his study of language in their villages and scout camps.

In the spring of 1877, two battalions of the Seventh Cavalry were sent west to join the army’s renewed campaigns against the Sioux and Cheyenne in Yellowstone Country. Miles’s Fifth Infantry had been campaigning in this remote country all winter. Following the rout of the Seventh Cavalry that June, General Philip Sheridan had planned “total war” against the Sioux from his headquarters in Chicago. Colonel Miles, in particular, did not intend to “hibernate” for the winter by holing up in a fort or cantonment. Instead, he believed that “a winter campaign could be successfully made against those Northern Indians, even in that extreme cold climate.”24 With troops augmented by civilian “Custer Avengers” and the full support of a Congress and nation prepared to pay any price “to end Sioux troubles for all time,” Miles led the Fifth Infantry in pursuit of hunting bands into the winter hunting grounds of Montana’s forbidding terrain.25 Following the hostilities of the summer, the matter uppermost in the minds of tribes as they dispersed along rivers to the east of the battleground was hunting to secure food and buffalo hides for the winter.26 They viewed the return of soldiers to the region with alarm and some puzzlement. It was not the accustomed season for war. In October, Sitting Bull left a note in the path of a wagon train carrying supplies intended for Miles’s winter garrison on the Tongue River that read:

I want to know what you are doing traveling on this road. You scare all the buffalos away. I want to hunt in this place. I want you to turn back from here. If you don’t I will fight you again. I want you to leave what you have got here and turn back from here.

I am your friend,

Sitting Bull

I mean all the rations you have got and some powder. Wish you would write as soon as you can.27

About a week later, Colonel Miles with the entire Fifth Infantry overtook Sitting Bull near Cedar Creek, Montana, north of the Yellowstone River. Over the course of two days, Miles met in council with Sitting Bull and other Lakota leaders: Pretty Bear, Bull Eagle, Standing Bear, Gall, and White Bear. Bent on provisioning their people for the winter and alarmed by the incursion of soldiers into their hunting country, the chiefs sought a truce for the winter. Sitting Bull made clear to Miles that their objective in the territory was to hunt buffalo and trade for ammunition. He did not want rations or annuities, but rather to live free and hunt in the open country. In return he offered that their side would not fire on the soldiers if they were left to hunt unmolested. Miles later reported that the Hunkpapa chief had asked him “why the soldiers did not go to winter quarters.” Miles rejected what he termed “an old-fashioned peace for the winter.”28 He informed Sitting Bull and the other principal men who had met in council with him that this offer was not acceptable to the government. Nothing short of his surrender at an agency and submission of his people to U.S. authority could stave off a war through the winter. Miles later expressed his view that “it was amusement for them to raid and make war during summer, but when constant relentless war was made upon them in the severest of winter campaigns it became serious and most destructive.”29

Determined to follow the Indians wherever they went, Miles fitted his men out with improvised winter gear, including leggings and mittens as well as face masks cut from woolen blankets.30 As the winter and the relentless raiding of Indian camps by the soldiers wore on, additional warm clothing was fashioned out of some of the hundreds of buffalo robes that were looted from the sacked encampments of the Lakota. A raid on Sitting Bull’s camp led by Frank D. Baldwin near the Milk River in December captured several hundred buffalo robes, which were fashioned into pants, overcoats, and caps by Cheyenne women who had capitulated. These were worn by Miles’s troops as they launched a January offensive up the Tongue River, where the Lakotas had gone in pursuit of the buffalo. This was the winter they gave Miles the name “Man-with-the-bear-coat.” Since the soldiers had looted or destroyed their lodges, utensils, tons of dried meat, and many horses and mules, they were both in need of fresh sup plies and demoralized by the constant harrying presence of the soldiers.31

In November Colonel Ranald S. Mackenzie had also dealt a devastating blow to the Cheyennes, raiding the village of Dull Knife (Morning Star) and Little Wolf, which consisted of about two hundred lodges in a canyon on the Red Fork of the Powder River. Thirty Cheyennes were killed in the raid. Those who survived were left with only what they could carry away. The soldiers burned the village and everything in it: meat, clothing, and all the tribe’s finery and art work. Seven hundred ponies were confiscated by the army. As the survivors fled north to seek refuge with Crazy Horse on the Tongue River, temperatures fell to thirty below zero. Eleven babies froze to death.32

Throughout the winter, the army’s campaigners pursued their quarry through the snow, across the frozen Missouri River. Facing starvation, killing cold, and the perpetual threat of the “long knives” of the U.S. Army wreaking havoc on their villages and threatening their families, many leaders made the decision to surrender to their agencies, where they were forced to give up their guns and thousands of horses. Red Horse explained the pressures that led him to surrender at the Cheyenne River Agency in February 1877. “I am tired of being always on the watch for troops. My desire is to get my family where they can sleep without being continually in the expectation of an attack.”33

By March only about fifteen lodges remained with Sitting Bull. Others had already crossed into Canada and Sitting Bull was considering this as an alternative to surrender or to continued harassment by the bluecoats. In May, around the time Scott was heading west with the Seventh Cavalry, Sitting Bull crossed the border with 135 Lakota lodges, totaling about a thousand people.

The anniversary of Custer’s defeat the previous year found Scott on the Big Horn battlefield, where his troop was assigned the task of recovering the bones of Custer and the other officers who had died there for reburial elsewhere as well as reburying the best they could the remains of others, which had been exposed by erosion in the intervening year. Following this detail, Scott and the rest of his troop reunited with their regiment near Fort Keogh on the Yellowstone. “The whole of the Northwest seemed very peaceable and the talk of the Seventh was that we should soon go back to Fort Lincoln. Everybody built sunshades over their tents and generally made themselves comfortable,” Scott recalled.34

Soon, however, word of hostilities erupting between the army and several Nez Percé tribal groups, who were being forced from their lands in Eastern Oregon, reached the command on the Yellowstone. As a Nez Percé group of some 250 warriors and 500 women and children along with thousands of horses and other livestock began an arduous trek through some of the wildest and most challenging terrain in the country, the Seventh Cavalry was split up and sent in various directions in an attempt to stop Chief Joseph and his dispossessed people from reaching sanctuary, like Sitting Bull, with the Canadian “Grandmother” across the border.

During the summer of 1877, Scott deepened his experience of working with scouts. He also developed an abiding interest in the way of life and customs of the indigenous nations with which the army brought him in contact. In July Miles sent him out to search for a Sioux war party on the Musselshell rumored to have come down from Canada. Scott accompanied some Northern Cheyenne scouts who had fought against Custer the previous summer and had only recently surrendered. The party included Two Moons, Little Chief, Hump, Black Wolf, Ice (or White Bull), Brave Wolf, and White Bear. Scott’s friends warned him against accompanying them, saying they would kill him and escape across the border to Canada, but Scott did not share these fears. Instead, he admired and learned from the Cheyenne warriors: “They were all keen, athletic young men, tall and lean and brave, and I admired them as real specimens of manhood more than any body of men I have ever seen before or since. They were perfectly adapted to their environment and knew just what to do in every emergency and when to do it, without any confusion or lost motion. Their poise and dignity were superb; no royal person ever had more assured manners. I watched their every movement and learned lessons from them that later saved my life many times on the prairie.”35

Scott also spent a lot of time with Crow scouts and observing life in the large Crow villages. On one occasion, exposure to the heat and insects of a Montana summer, against which his army issue tent provided insufficient protection, led him to seek hospitality in the lodge of Iron Bull. Seeking respite from sun, dust, and flies, Scott presented himself at the entrance of the huge buffalo-hide lodge of the Crow chief. The hide lodge cover, which was made in two pieces from the hides of twenty-five buffalo, was well smoked from the fire, so that the sun did not penetrate. Scott estimated the poles supporting the covering to be twenty-five feet long and five inches in diameter. It took six horses to transport them. Entering the lodge, Scott wrote, was like “passing at once into a new world.” Inside, it was cool and there were no flies. “Beds of buffalo robes were all around the wall, and the floor was swept clean as the palm of one’s hand.” Addressing Iron Bull, who was lying on his back in bed wearing only a breechclout, Scott said, “Brother, I want to come and stay in here with you until we leave.” Ac cordingly, Scott abandoned the porous white canvas of his “bit of a tent,” and instead was made “most welcome” in the lodge of the Crow chief and his wife.36

On this and other occasions, Scott paid close attention to the village life taking place around him. Besides providing ethnographic information and military intelligence, Indian village life on the prairie was a source of intense interest and often delight. During the summer of 1877, he traveled with a large village of Crow Indians near the Big Bend of the Musselshell. Encompassing about three thousand people from various mountain and river bands of Crows, the camp moved often to find grass for their large herd of horses. They hunted buffalo about once a week to provide meat for such a large group. Scott was fascinated by the great village and the life he observed there:

The camp had meat drying everywhere. Everybody was care-free and joyous in a way we do not comprehend in this civilized day. All the life of a nation was going on there before our eyes. Here the head chiefs were receiving ambassadors from another tribe. Following the sound of drums, one would come upon a great gathering for a war-dance, heralding an expedition to fight the Sioux. Or one came to a lodge where a medicine-man was doctoring a patient to the sound of a drum and rattle. Elsewhere a large crowd surrounded a game of ring and spear, on which members of the tribe were betting everything they owned: the loser lost without dispute or quiver of an eyelid. In another place a crowd was witnessing a horse race with twenty-five horses starting off at the first trial…. All day and far into the night there was something happening of intense interest to me.37

After the army, led by Nelson Miles, finally caught up with Chief Joseph and the exhausted bands of Nez Percé in the foothills of the Bears Paw mountains and fought them to defeat, Scott spent time in the Big Open country of Montana searching for Nez Percé who had escaped capture. From Fort Buford to Bismarck—225 miles along the Missouri River—Scott’s Troop I served as an escort for Chief Joseph and the Nez Percé prisoners who were being transported to the end of the railroad to be shipped to prison from Bismarck by rail. In spite of Miles’s promise to Chief Joseph that he and his people would spend the winter at the Tongue River Cantonment and then return to the Pacific Northwest in the spring, they were not allowed back to their homeland. Instead, they were forced to go to Fort Leavenworth. After a terrible winter at Fort Leavenworth, they were sent first to the Quapaw Reservation in Indian Territory (present-day northern Oklahoma), which they called “Eikish Pah” or hot place. Chief Joseph remained in exile until his death in 1904.38

From a Nez Percé called Tippit, Scott was able to learn some Chinook, an intertribal language used on the Columbia River and up the Pacific Coast. As they rode along the Musselshell River toward its confluence with the Missouri, where the Seventh Cavalry was camped, Scott induced Tippit to pose questions in Chinook followed by answers aimed at conveying their English translations.39 On the same trip, he spent time in the wagons with Sioux and Cheyenne scouts, working on improving both spoken and sign language. Another part of each day he spent in Chief Joseph’s wagon, along with a Nez Percé translator from Idaho named Arthur Chapman. During a stop at Fort Berthold, members of the Hidatsa, Mandan, and Gros Ventre tribes gathered in a large council to learn of the tribulations of Chief Joseph, who spoke in sign language to some fifteen hundred people representing eight different languages (Nez Percé, Cheyenne, Sioux, Crow, Mandan, Arikara, Gros Ventre of the Village, and English). Scott wrote that Chief Joseph was “completely understood by all that vast concourse.”40

A couple of months after returning to Fort Lincoln for the winter, Scott resumed his study of the sign language under the tutelage of White Bear and other members of the Cheyenne band captured by Miles the previous year, who had been brought as prisoners to spend the winter at the post. Scott visited the Cheyenne prisoners’ village regularly. There, in exchange for his language lessons, he subsidized White Bear with coffee, sugar, and other rations. During one visit to the Indian camp, White Bear told Scott that the group was planning to run away that night to go back to the buffalo country leaving all their lodges standing. He complained that the rations their families were issued for ten days were not sufficient to feed them even for three. Therefore, they had packed their belongings and were prepared to make a break. Not entirely believing what he was hearing, Scott moved as casually as he could among other lodges of the village and confirmed that, indeed, the Cheyennes had packed up their movable property and were preparing to leave. Scott quickly returned to the post and reported the plans for escape to his commanding officer. A squadron of cavalry were then dispatched to guard the camp and prevent them from leaving as planned. Scott received formal commendation for his discovery of the planned escape and for his “knowledge of the Indian’s character, his human nature, his method and thought of action, and of the Indian Sign Language.”41

Scott’s growing reputation as an interpreter and as a man who knew Indian character led to an assignment the following year as an interpreter for the army in its dealings with the Oglala chief Red Cloud, who had broken away without permission from his agency, taking the agency beef herd along with him. In reality, Scott’s assignment was to keep Red Cloud under observation and discover what had upset him and what his intentions were. Under these strained circumstances, Scott spent three days in Red Cloud’s lodge, essentially as a spy. Even though he was at best an imposed guest, Scott found Red Cloud to be “the picture of hospitality.” The two men passed the time conversing in sign language. Scott wrote about the incident in his memoirs: “Red Cloud was an excellent sign talker, but he made his gestures differently from any one I had ever seen before or since. While each was perfectly distinct, they were all made within the compass of a circle a foot in diameter, whereas they are usually made in the compass of a circle two and a half feet in diameter. We talked about everything under the sun, but he would not give me any clue to what made him so ill-humored, and to what was actuating his young men.”42 Scott learned much later that Red Cloud’s flight from the reservation had been triggered by the mobilization of army troops from Fort Laramie and several other points to rendezvous near Pine Ridge. Fearing that the troops were coming to arrest him, Red Cloud had fled with around five thousand of his community and they remained suspicious of and angry with the whites for the harassment and aggression they experienced.

In the parlance of modern anthropology, Scott gained his knowledge of Indian language and culture through participant-observation. He was not alone in valuing the kind of knowledge to be gained by such methods, nor in pursuing it, but the science of ethnology, as it was called at the time, was in its infancy. It was more concerned with the study of kinship and theorizing the stages of human progress, such as those on display at the Centennial Exposition, and not so developed as it would become with respect to what we now recognize as the ethnographic method. Yet Scott and a handful of other officers were practicing it in the context of the army’s work with Indians on the frontier.43

Scott’s ethnographic techniques were not limited to the study of sign language; he extended his close and critical observation to the landscape and culture of Native North America more generally. Observations and analysis of the behaviors of animals, including other humans, were part of the repertoire of the scout, providing valuable tactical knowledge of the surroundings in which the complex strategies of assessing, anticipating, and pursuing the enemy were carried out. By learning to recognize the differences in the grazing habits and differing behaviors among herd animals such as horses, cattle, and buffaloes, for example, Scott was able to gain clues about the proximity and actions of other groups of people associated with the animals, such as the Crows. Scott felt that the cultivation of such techniques of reading the landscape separated him from soldiers on the frontier who never learned to read such signs. “Many were first-rate garrison soldiers, who knew their drill, took good care of their men, and who never made a mistake in their muster-rolls,” he wrote. “But [they] were blind on the prairie.”44

Scott proceeded on the idea that every action had a motive that could be discerned. As a hunter he had long studied the laws governing the actions of various animals. Scott believed that all animals were governed by “laws of their nature that compel each kind to do the same thing under the same circumstances.” Some of these he prided himself on learning through his own observation, for example, those governing the behavior of rabbits and ducks. The laws governing the movement of black bears, mountain sheep, and black-tailed deer he learned from watching the movements of Crows, Caddos, Sioux, and Cheyenne while hunting. He also believed there was a motive for human actions, which could be discerned. Indians, however, according to Scott, could not themselves articulate the reasons they hunted these animals in certain ways. The only way of learning these secrets lay in Scott’s close observation and analysis. “They cannot give one their reasons for doing certain things,” he wrote. “The only means of learning lies in close observation.” He expounded on this theory in his book. Indians were not always able to recognize the motives for their own actions, but he believed that he could ascertain them by posing questions and by observing and analyzing their behavior.45 An example of this method at work is in Scott’s account of how he went about finding out what made a good buffalo-hunting horse in the Crows’ estimation. Scott’s inquiry into this topic, which was of existential importance to people who depended on the buffalo, began by close observation of the methods of hunting. Scott also asked questions, and in at least one case, provoked discussion among his informants so that he could learn from their exchange of ideas. In 1877, while traveling with the Crows, he instigated a debate among the chiefs in council as to who had the best buffalo horse. “After a week it was determined that Iron Bull Chief of the Montana Crows had him, and on the next run I borrowed him to find out what a really fine buffalo horse was like,” Scott wrote. After riding the best buffalo horse, Scott went on to borrow the second best and so on “until I had ridden twenty-five out of the cream of over 12,000 head—the great majority of which were pack horses and mares and colts.” From this experience, Scott noted some significant points about what made a good buffalo horse: “He did not have to be fought with like our [cavalry] horses. All he needed was to be pointed at the animal selected; then he would take one so close that one could put his hand on the buffalo’s back if one wished.”46 In his memoirs, Scott reflected wryly that he must have been a “sore trial” to the native informants whom he badgered over the years, “boring away at a subject they were unable to elucidate” until he had found the motive, which Scott thought they were often unable to formulate themselves.47

In the beginning, Scott’s interest in ethnographic knowledge was instrumentalist. In particular, he applied himself to acquiring a mastery of sign language and other languages as a means of furthering his career in the army and securing more satisfying work for himself as well as winning respect and stature. However, Scott quickly became interested in learning all that he could about Indians. What began as a strategy to achieve advancement and autonomy developed into a profound lifelong interest in indigenous languages and customs.

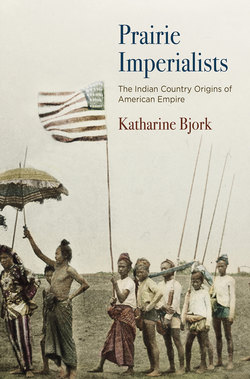

Figure 3. Hunting party on the Washita River in the Kiowa-Comanche-Apache Reservation. The group includes Hugh Lenox Scott (standing, third from left), Mary Scott (seated in front of him), Lieutenant Oscar Charles (seated on the ground next to Mary). Also pictured are General Nelson Miles and Frank Baldwin, who was then the Indian agent at Anadarko. Prints and Photographs Division, Library of Congress.

In 1889 Scott was assigned to Troop M of the Seventh Cavalry at Fort Sill in what was then Indian Territory. Scott’s tenure at Fort Sill coincided with a transformation of the role of Indians in the army. Although still referred to as scouts, after 1891 Native men were enlisted directly in the army. In each of the twenty-six regiments of Infantry and Cavalry serving west of the Mississippi except for the black units, one company or troop was reorganized as an all-Indian unit. Thus, Troop L of the Seventh Cavalry, a unit ironically wiped out at the Battle of Little Big Horn, was reconstituted at Fort Sill in 1891 as an Indian Scout troop. Initially, all officers were white, although later Indians served as noncommissioned officers. From June 1891 to May 1897, Troop L was composed of a majority of Kiowas, Comanches, and Apaches. After 1894, some of the Apache prisoners who had been resettled from Florida and Alabama to Fort Sill also served in Troop L under Scott’s command.48

By the time he made the move to Oklahoma, Scott was widely recognized as an expert on sign language both within and outside the army. Scott was one of a number of frontier officers who kept up a correspondence with the Bureau of Ethnology after its founding in 1879 under the direction of John Wesley Powell. He also wrote to missionaries and corresponded with foreign experts on sign language, such as Ernest Thompson Seton, the British artist and author who founded the Woodland Indians to promote woodcraft and scouting among white boys. When Seton wrote his book Sign Language for Scouting, he sent a copy to Scott for his comments. “I hope you will scribble as freely as you feel disposed on the [manuscript],” Seton wrote to him. “Of course you know I attach the greatest importance to everything you say about sign language. You are admitted to be the greatest living authority on the sign language of the Indians.”49 Perhaps the Englishman was engaging in some strategic flattery, but in fact, there were few nonnative signers who shared Scott’s interest, experience, and facility with the language. In addition to Scott’s study of vocabulary, he also wrote thoughtfully on the structure of the sign language and analyzed how its properties were analogous to those of spoken language. He recognized sign language as a living, evolving language, with its own rules and grammar, although he persisted in fitting it into a hierarchy of languages in which some (like the sign language) were primitive and some were more advanced. Scott’s thinking about the evolution of increasingly complex language was consistent with prevailing racial ideas, such as those informing the exhibitions at the Centennial Exposition.50

Soon after arriving at Fort Sill, Scott was detailed by the post commander to study the religious movement known as the Ghost Dance among the Indians of western Indian Country. In December 1890 the War Department commissioned him to investigate the meaning and causes of the movement and assess whether it constituted a danger to white settlers, who had become alarmed by the rumors of possible uprisings linked to the new craze. From 1890 through February 1891, Scott visited camps in the vicinity of Fort Sill, observed dances, and interviewed practitioners about the meaning and power of the religion and its rituals.51

To carry out these inquiries among eight tribes in the western part of Indian Territory, Scott recruited several Indian soldiers from Troop L, including Sergeant Iseeo, who became one of Scott’s closest associates and collaborators in his ethnographic work. In addition to Iseeo, the investigating party included several enlisted Indian soldiers who served as orderly, scout, cook, and driver. So as not to alarm the Ghost Dancers they visited, the group traveled under the guise of being a hunting party, obscuring the true interests of their expedition.52 Of course, at the same time Scott was leading his ethnographic fact-finding tour through Oklahoma, preoccupation with the Ghost Dance was reaching a crisis point among whites on and near the Sioux Reservation to the north. In fact, as Scott’s undercover ethnographers gathered information and formed an impression of the movement on the southern plains, the largest army assembled since the Civil War was converging on the Sioux agencies from around the country. By the end of December, overreaction to the religious movement had led to the tragic killing of more than 250 Lakota as well as a number of soldiers of the Seventh Cavalry when they attempted to disarm Big Foot’s Minnecounjous on Wounded Knee Creek.

In contrast to the semi-hysterical view of some in the civil Indian service and many anxious settlers around the reservations, who worried that the vision of a world in which whites had been replaced by resurgent buffalo would be sought through violence against them, Scott’s conclusion was that the dance was purely religious and posed no threat. “These songs and the dance itself are of a purely religious character,” he wrote. “Being a prayer to and worship of the same Jesus the white man worships and who has come down in the North.” As far as threatening violence to whites in order to bring about the prophecy of a restoration of buffalo and the return of dead relatives, Scott wrote: “The doctrine of the separation of races, the red man from the white called for no action on the part of the former, it was to be accomplished by supernatural means alone Jesus was to do it all that the red man had to do was to push this dance and stand by see it done and reap the benefits.”53 Scott counseled that the dance be allowed to run its course without interference, “that the whole structure would fall from nonfulfilment of the prophesies.”54

Scott wrote up the findings of his ethnographic hunting trip in a paper for the Fort Sill Lyceum the following winter. Several things emerge from this report. One is Scott’s wry and ironic sense of humor. Commenting on the wide appeal of the Ghost Dance prophecy of the resurrection of dead relatives and their return to earth, Scott noted an exception to the general happiness at the prospect of being reunited with lost dear ones. “These tidings brought great joy to all who heard them,” he wrote. “Except to Tabananaca the Comanche Chief who did not relish the idea of furnishing all his departed relatives with horses from his large herd.”55

Scott’s report is also notable for the level of detail and nuanced and contextualized ethnographic description it provides. Take, for example, his description of the ritual at the center of the controversy over the movement, the dance itself. First, he provided a precise description, revealing both attentive observation and his ability to convey the details of unfamiliar practice in understandable terms.

Our first view of the dance was at a small Kiowa Camp in the northern foot hills of the Wichita Mountains; there nicely sheltered from the cold winds from the north in a timbered bend of Sulphur Creek was found the village, the lodges arranged in the shape of a horse_shoe. When we arrived there were gathered together in a ring in the open space in the centre of the horse_shoe about fifty people having hold of each others hands the fingers interlocked dancing with a peculiar side step. the mechanism of which seems to be : first the weight of the body being on the right leg the right knee is bent lowering the body slightly then a short step is made to the left with the left foot, the weight is then transferred to the left leg which is immediately straightened, the right foot brought to the side of the left and the weight again placed upon the right leg, this is repeated continuously all keeping time to the singing.56

To this he added his own analysis and commentary on the dance.

The music of these songs is unique and distinctive; none of us had ever heard anything precisely like it. The Messiah songs could be distinguished at once from the war songs or those used at the “wokowie” feasts or sun dances by the character of the music even if the words and air were unknown. There was a great variety to the songs, some owing to the minor key in which they were sung were very weird some were low rich and beautiful but all had a certain monotony owing to the fact that each line was repeated and the song itself sung over and over again in making each round of the circle: yet all were pleasing one especially delighting us, it gave all the impressions of a noble chant and when sung by a large concourse of people in the moonlight with the wild surroundings the peculiar accompaniment of the crying and the solemn dance, its effect was most striking and will never be forgotten by those who heard it.57

Scott made sense of the landscape and the work before him by recourse to another nineteenth-century heuristic for knowing and classifying the natural world: collecting. The nineteenth century gave rise to all kinds of colonial collecting. From geology to folklore, amateurs with natural curiosity and a scientific bent searched places both familiar and remote for everything from fossils to birds’ nests.

As would be the case later in the Philippines and Cuba, Scott’s early attempts to know his surroundings and to make sense of them relied heavily on classifying and articulating the similarities and differences among classes of things, creating a typology and then elaborating and refining it. Thus, an early letter home to his mother from Fort Lincoln bragged that in his first year in the Northwest he had seen “nearly all” the Indians with whom the army had dealings. He proceeded to provide a typology for his mother, clearly informed by his own cultural categories and values and also attuned—one suspects—to his knowledge of his mother’s prejudices. “The Cheyennes are the Indians I like. The braves—cleaner and more manly in every way than any I’ve seen in the Northwest and I’ve seen nearly all of them—the Nez Perces are too much like the Crows and of all horrible cowardly wretches the Crows are the worst—the Nez Perces are not cowardly, but in stature, appearance dress hair & filth they are very much alike—the Yanktonais Siouxs don’t pan out well or the Assiniboines or the Rees Mandans or Gros Ventres—the Cheyennes beat them all.”58 Confident of his young man’s ability to judge types of men, although he had as yet little knowledge of them, his early assessments reflected most of all the prejudices of the East and of the civilization from which Scott came. To a great extent, Scott’s close and interested association with Native peoples over the next two decades of service in Indian Country led him to move away from such crude typologies. With more experience with Indian scouts and more time spent actively seeking ethnographic knowledge for strategic military purposes in Indian villages, Scott’s knowledge progressed increasingly beyond such superficial and impressionistic typologies. What started out as little more than a cataloging of tribes in a way that reinscribed the stereotypes and prejudices available to him through the dominant Indian-hating culture, developed over time into a more finely tuned ethnographic sensibility. Interestingly, he later wrote not just with sensitivity but with admiration of the village life of the Crows in particular, the group that seems to have provoked the disdainful assessment he expressed in his letter to his mother during his first winter in Indian Country.

Scott’s penchant for classifying and collecting, on the other hand, increased over time. Like many soldiers, Scott had a taste for exotic memorabilia and trophies collected in the field. He collected artifacts for their intrinsic curiosity value as well as with awareness of their more practical exchange value in his own society. Half a century after the event, he ruefully recounted the loss of six fine Crow buffalo robes lost in the course of trading duties with another officer during the Nez Percé campaign.59 The most significant collecting Scott did was carried out during the nine years he spent at Fort Sill in Oklahoma (1889–97). His home at Fort Sill became a veritable museum of artifacts of all kinds, from feather work to pottery to hides and weapons.

Several years after Scott’s return from Oklahoma to the East, a collection of 124 artifacts he had collected during his time in the Southwest was acquired by Phoebe Hearst (mother of William Randolph Hearst) and became the foundation for the collection of the Phoebe A. Hearst Museum of Anthropology at the University of California, Berkeley. The objects sold to Mrs. Hearst were all things he had collected from the Kiowa and Apaches, including clothing, cooking and household objects, ceremonial calendars, and baskets, as well as shields, clubs, bows, and arrows.60

Scott carried his enthusiasm for collecting to Cuba and the Philippines. Like other soldiers abroad, he collected and sent home trophies. In a nod to his guru Parkman, he described some medals and military decorations he sent his wife from Cuba as “spoil of the Spaniard” (and cautioned her not to wear them anywhere she was likely to encounter any Europeans). In addition to a set of Cuban stocks he sent to Woodrow Wilson at Princeton, he also collected weapons in the Philippines.

Figure 4. Artifacts on display in Scott’s Fort Sill home. Prints and Photographs Division, Library of Congress.

Without question, the most significant collecting Scott did was his work to record legends, history, and linguistic information from the people of the southern plains during his nine years at Fort Sill, detailing several of the scouts in his troop to travel to villages in a large region around the fort tracking down words, signs, and stories. The ledgers he compiled at Fort Sill have survived as a unique source of ethnographic information collected through the medium of sign language about the life and history of the Kiowa, Comanche, and other peoples interviewed in the vicinity of the Fort.61 He also used the tours of inspection of Indian reservations on which the Board of Indian Commissioners sent him to continue his studies of culture and language in the 1920s.

In the research he began at the Bureau of Ethnology after leaving Fort Sill in 1897, Scott tracked down a few scanty observations on sign language in the records of European explorers dating back to the expeditions of Álvar Núñez Cabeza de Vaca and Francisco Vásquez de Coronado in the mid-sixteenth century. He also studied the journals of the Lewis and Clark expedition looking for evidence of the Corps of Discovery’s awareness of the use of this lingua franca among many of the Native nations they encountered on their trek up the Missouri. Scott was struck by how little notice earlier colonizers had taken of sign language. In an early draft for the book he never completed, he wrote: “I have always been amazed at the little attention the Singlangue has received in the past especially soldiers and explorers—for it is certainly a wonderful language and most useful to the above classes—for 200 years—but instead of perfecting themselves in its use they have merely left a reference apparently to show that they knew of its existence—this is the more remarkable in the case of Lewis & Clark 1804–6 whose was directed by President Jefferson to investigate every thing they found that was new and interesting.”62 Besides the history of sign language, its spread throughout the central plains region, and its military and diplomatic utility, Scott was also interested in it as a linguistic phenomenon. He faulted others who had written on the subject with failing to recognize it as a natural language “subject to all the general laws of linguistic science, save those of sound … [having] its own place in the hierarchy of all human speech, akin to all through our common humanity.”63

Even though Scott had an appreciation for the adaptability and expressiveness of sign language, he nonetheless theorized it as representing a simple root stage of language, analogous to the primitive germ out of which more advanced languages, such as Indo-European speech “with all its fullness and inflective suppleness,” had descended over generations. In this he seems to have been influenced by the views of the evolution of complex language put forward in the work of Yale University philologist William Whitney.64

Scott’s research for his book on sign language was cut short by the start of the Spanish-American War. By his own account, he then became “engaged for years in matters more important to [his] career than writing any book.”65 There is evidence that he continued to think about the project, however, even when he was in the Philippines. In a letter to his wife written when he was governor of Sulu in 1905, Scott asked Mary to send him some books on linguistics. Specifically, he asked her to buy a book on “deaf & mute language showing its structure etc—not of the artificial alphabetic language but the natural language of the deaf.” He wrote that Dr. Gallaudet of Washington could help identify the kind of thing he was interested in. He also asked her to send him several other books that he had used to prepare a talk General Nelson Miles had asked him to give on sign language at the Columbian Exposition in Chicago in 1893. These included works on linguistics by Max Müller, F. W. Farrar, and A. H. Sayce. “I seem to want to know something about the real essence of spoken language,” Scott explained to his wife, “but the thing has become dim & I am in the mood for it now if I had the books—as it all bears on sign language more or less.”66 Several letters requesting materials from libraries in Texas suggest he had renewed efforts on his research again during the time he was stationed in San Antonio in 1911 and 1912 with the Third Cavalry.67

Scott’s interest in sign language had its origin in his passion for scouting and his ambition to make himself useful to commanding officers and to the frontier army, which he did. As that same army faced the challenges of an expanding overseas empire, Scott would continue to be called on to put his scouting skills to work—on the new frontiers of that empire in Cuba and the Philippines, and eventually back on the border with Mexico.