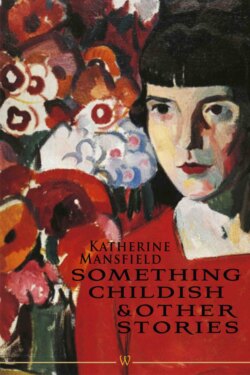

Читать книгу Something Childish and other Stories - Katherine Mansfield - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

NEW DRESSES

ОглавлениеMrs. Carsfield and her mother sat at the dining-room table putting the finishing touches to some green cashmere dresses. They were to be worn by the two Misses Carsfield at church on the following day, with apple-green sashes, and straw hats with ribbon tails. Mrs. Carsfield had set her heart on it, and this being a late night for Henry, who was attending a meeting of the Political League, she and the old mother had the dining-room to themselves, and could make “a peaceful litter” as she expressed it. The red cloth was taken off the table—where stood the wedding-present sewing machine, a brown work-basket, the “material,” and some torn fashion journals. Mrs. Carsfield worked the machine, slowly, for she feared the green thread would give out, and had a sort of tired hope that it might last longer if she was careful to use a little at a time; the old woman sat in a rocking chair, her skirt turned back, and her felt-slippered feet on a hassock, tying the machine threads and stitching some narrow lace on the necks and cuffs. The gas jet flickered. Now and again the old woman glanced up at the jet and said, “There’s water in the pipe, Anne, that’s what’s the matter,” then was silent, to say again a moment later, “There must be water in that pipe, Anne,” and again, with quite a burst of energy, “Now there is—I’m certain of it.”

Anne frowned at the sewing machine. “The way mother harps on things—it gets frightfully on my nerves,” she thought. “And always when there’s no earthly opportunity to better a thing...I suppose it’s old age—but most aggravating.” Aloud she said: “Mother, I’m having a really substantial hem in this dress of Rose’s—the child has got so leggy, lately. And don’t put any lace on Helen’s cuffs; it will make a distinction, and besides she’s so careless about rubbing her hands on anything grubby.”

“Oh there’s plenty,” said the old woman. “I’ll put it a little higher up.” And she wondered why Anne had such a down on Helen—Henry was just the same. They seemed to want to hurt Helen’s feelings—the distinction was merely an excuse.

“Well,” said Mrs. Carsfield, “you didn’t see Helen’s clothes when I took them off to-night, Black from head to foot after a week. And when I compared them before her eyes with Rose’s she merely shrugged, you know that habit she’s got, and began stuttering. I really shall have to see Dr. Malcolm about her stuttering, if only to give her a good fright. I believe it’s merely an affectation she’s picked up at school—that she can help it.”

“Anne, you know she’s always stuttered. You did just the same when you were her age, she’s highly strung.” The old woman took off her spectacles, breathed on them, and rubbed them with a corner of her sewing apron.

“Well, the last thing in the world to do her any good is to let her imagine that” answered Anne, shaking out one of the green frocks, and pricking at the pleats with her needle. “She is treated exactly like Rose, and the Boy hasn’t a nerve. Did you see him when I put him on the rocking-horse to-day, for the first time? He simply gurgled with joy. He’s more the image of his father every day.”

“Yes, he certainly is a thorough Carsfield,” assented the old woman, nodding her head.

“Now that’s another thing about Helen,” said Anne. “The peculiar way she treats Boy, staring at him and frightening him as she does. You remember when he was a baby how she used to take away his bottle to see what he would do? Rose is perfect with the child—but Helen...”

The old woman put down her work on the table. A little silence fell, and through the silence the loud ticking of the dining-room clock. She wanted to speak her mind to Anne once and for all about the way she and Henry were treating Helen, ruining the child, but the ticking noise distracted her. She could not think of the words and sat there stupidly, her brain going tick, tick, to the dining-room clock.

“How loudly that clock ticks,” was all she said.

“Oh there’s mother—off the subject again—giving me no help or encouragement,” thought Anne. She glanced at the clock.

“Mother, if you’ve finished that frock, would you go into the kitchen and heat up some coffee, and perhaps cut a plate of ham. Henry will be in directly. I’m practically through with this second frock by myself.” She held it up for inspection. “Aren’t they charming? They ought to last the children a good two years, and then I expect they’ll do for school—lengthened, and perhaps dyed.”

“I’m glad we decided on the more expensive material,” said the old woman.

Left alone in the dining-room Anne’s frown deepened, and her mouth drooped—a sharp line showed from nose to chin. She breathed deeply, and pushed back her hair. There seemed to be no air in the room, she felt stuffed up, and it seemed so useless to be tiring herself out with fine sewing for Helen. One never got through with children, and never had any gratitude from them—except Rose—who was exceptional. Another sign of old age in mother was her absurd point of view about Helen, and her “touchiness” on the subject. There was one thing, Mrs. Carsfield said to herself. She was determined to keep Helen apart from Boy. He had all his father’s sensitiveness to unsympathetic influences. A blessing that the girls were at school all day!

At last the dresses were finished and folded over the back of the chair. She carried the sewing machine over to the book-shelves, spread the table-cloth, and went over to the window. The blind was up, she could see the garden quite plainly: there must be a moon about. And then she caught sight of something shining on the garden seat. A book, yes, it must be a book, left there to get soaked through by the dew. She went out into the hall, put on her goloshes, gathered up her skirt, and ran into the garden. Yes, it was a book. She picked it up carefully. Damp already—and the cover bulging. She shrugged her shoulders in the way that her little daughter had caught from her. In the shadowy garden that smelled of grass and rose leaves, Anne’s heart hardened. Then the gate clicked and she saw Henry striding up the front path.

“Henry!” she called.

“Hullo,” he cried, “what on earth are you doing down there...Moon-gazing, Anne?” She ran forward and kissed him.

“Oh, look at this book,” she said. “Helen’s been leaving it about, again. My dear, how you smell of cigars!”

Said Henry: “You’ve got to smoke a decent cigar when you’re with, these other chaps. Looks so bad if you don’t. But come inside, Anne; you haven’t got anything on. Let the book go hang! You’re cold, my dear, you’re shivering.” He put his arm round her shoulder. “See the moon over there, by the chimney? Fine night. By jove! I had the fellows roaring to-night—I made a colossal joke. One of them said: ‘Life is a game of cards,’ and I, without thinking, just straight out...” Henry paused by the door and held up a finger. “I said...well I’ve forgotten the exact words, but they shouted, my dear, simply shouted. No, I’ll remember what I said in bed to-night; you know I always do.”

“I’ll take this book into the kitchen to dry on the stove-rack,” said Anne, and she thought, as she banged the pages, “Henry has been drinking beer again, that means indigestion tomorrow. No use mentioning Helen to-night.”

When Henry had finished the supper, he lay back in the chair, picking his teeth, and patted his knee for Anne to come and sit there.

“Hullo,” he said, jumping her up and down, “what’s the green fandangles on the chair back? What have you and mother been up to, eh?”

Said Anne, airily, casting a most careless glance at the green dresses, “Only some frocks for the children. Remnants for Sunday.”

The old woman put the plate and cup and saucer together, then lighted a candle.

“I think I’ll go to bed,” she said, cheerfully.

“Oh, dear me, how unwise of Mother,” thought Anne. “She makes Henry suspect by going away like that, as she always does if there’s any unpleasantness brewing.”

“No, don’t go to bed yet, mother,” cried Henry, jovially. “Let’s have a look at the things.” She passed him over the dresses, faintly smiling. Henry rubbed them through his fingers.

“So these are the remnants, are they, Anne? Don’t feel much like the Sunday trousers my mother used to make me out of an ironing blanket. How much did you pay for this a yard, Anne?”

Anne took the dresses from him, and played with a button of his waistcoat.

“Forget the exact price, darling. Mother and I rather skimped them, even though they were so cheap. What can great big men bother about clothes...? Was Lumley there, tonigh?”

“Yes, he says their kid was a bit bandylegged at just the same age as Boy. He told me of a new kind of chair for children that the draper has just got in—makes them sit with their legs straight. By the way, have you got this month’s draper’s bill?”

She had been waiting for that—had known it was coming. She slipped off his knee and yawned.

“Oh, dear me,” she said, “I think I’ll follow mother. Bed’s the place for me.” She stared at Henry, vacantly. “Bill—bill did you say, dear? Oh, I’ll look it out in the morning.”

“No, Anne, hold on.” Henry got up and went over to the cupboard where the bill file was kept. “To-morrow’s no good—because it’s Sunday. I want to get that account off my chest before I turn in. Sit down there—in the rocking-chair—you needn’t stand!”

She dropped into the chair, and began humming, all the while her thoughts coldly busy, and her eyes fixed on her husband’s broad back as he bent over the cupboard door. He dawdled over finding the file.

“He’s keeping me in suspense on purpose,” she thought. “We can afford it—otherwise why should I do it? I know our income and our expenditure. I’m not a fool. They’re a hell upon earth every month, these bills.” And she thought of her bed upstairs, yearned for it, imagining she had never felt so tired in her life.

“Here we are!” said Henry. He slammed the file on to the table.

“Draw up your chair...”

“Clayton: Seven yards green cashmere at five shillings a yard—thirty-five shillings.” He read the item twice—then folded the sheet over, and bent towards Anne. He was flushed and his breath smelt of beer. She knew exactly how he took things in that mood, and she raised her eyebrows and nodded.

“Do you mean to tell me,” stormed Henry, “that lot over there cost thirty-five shillings—that stuff you’ve been mucking up for the children. Good God! Anybody would think you’d married a millionaire. You could buy your mother a trousseau with that money. You’re making yourself a laughing-stock for the whole town. How do you think I can buy Boy a chair or anything else—if you chuck away my earnings like that? Time and again you impress upon me the impossibility of keeping Helen decent; and then you go decking her out the next moment in thirty-five shillings worth of green cashmere...”

On and on stormed the voice.

“He’ll have calmed down in the morning, when the beer’s worked off,” thought Anne, and later, as she toiled up to bed, “When he sees how they’ll last, he’ll understand...”

A brilliant Sunday morning. Henry and Anne quite reconciled, sitting in the dining-room waiting for church time to the tune of Carsfield junior, who steadily thumped the shelf of his high-chair with a gravy spoon given him from the breakfast table by his father.

“That beggar’s got muscle,” said Henry, proudly. “I’ve timed him by my watch. He’s kept that up for five minutes without stopping.”

“Extraordinary,” said Anne, buttoning her gloves. “I think he’s had that spoon almost long enough now, dear, don’t you? I’m so afraid of him putting it into his mouth.”

“Oh, I’ve got an eye on him.” Henry stood over his small son. “Go it, old man. Tell Mother boys like to kick up a row.”

Anne kept silence. At any rate it would keep his eye off the children when they came down in those cashmeres. She was still wondering if she had drummed into their minds often enough the supreme importance of being careful and of taking them off immediately after church before dinner, and why Helen was fidgety when she was pulled about at all, when the door opened and the old woman ushered them in, complete to the straw hats with ribbon tails.

She could not help thrilling, they looked so very superior—Rose carrying her prayer-book in a white case embroidered with a pink woollen cross. But she feigned indifference immediately, and the lateness of the hour. Not a word more on the subject from Henry, even with the thirty-five shillings worth walking hand in hand before him all the way to church. Anne decided that was really generous and noble of him. She looked up at him, walking with the shoulders thrown back. How fine he looked in that long black coat, with the white silk tie just showing! And the children looked worthy of him. She squeezed his hand in church, conveying by that silent pressure, “It was for your sake I made the dresses; of course you can’t understand that, but really, Henry.” And she fully believed it.

On their way home the Carsfield family met Doctor Malcolm, out walking with a black dog carrying his stick in its mouth. Doctor Malcolm stopped and asked after Boy so intelligently that Henry invited him to dinner.

“Come and pick a bone with us and see Boy for yourself,” he said. And Doctor Malcolm accepted. He walked beside Henry and shouted over his shoulder, “Helen, keep an eye on my boy baby, will you, and see he doesn’t swallow that walking-stick. Because if he does, a tree will grow right out of his mouth or it will go to his tail and make it so stiff that a wag will knock you into kingdom come!”

“Oh, Doctor Malcolm!” laughed Helen, stooping over the dog, “Come along, doggie, give it up, there’s a good boy!”

“Helen, your dress!” warned Anne.

“Yes, indeed,” said Doctor Malcolm. “They are looking top-notchers to-day—the two young ladies.”

“Well, it really is Rose’s colour,” said Anne.

“Her complexion is so much more vivid than Helen’s.”

Rose blushed. Doctor Malcolm’s eyes twinkled, and he kept a tight rein on himself from saying she looked like a tomato in a lettuce salad.

“That child wants taking down a peg,” he decided. “Give me Helen every time. She’ll come to her own yet, and lead them just the dance they need.”

Boy was having his mid-day sleep when they arrived home, and Doctor Malcolm begged that Helen might show him round the garden. Henry, repenting already of his generosity, gladly assented, and Anne went into the kitchen to interview the servant girl.

“Mumma, let me come too and taste the gravy,” begged Rose.

“Huh!” muttered Doctor Malcolm. “Good riddance.”

He established himself on the garden bench—put up his feet and took off his hat, to give the sun “a chance of growing a second crop,” he told Helen.

She asked, soberly: “Doctor Malcolm, do you really like my dress.”

“Of course I do, my lady. Don’t you?”

“Oh yes, I’d like to be born and die in it, But it was such a fuss—tryings on, you know, and pullings, and ‘don’ts.’ I believe mother would kill me if it got hurt. I even knelt on my petticoat all through church because of dust on the hassock.”

“Bad as that!” asked Doctor Malcolm, rolling his eyes at Helen.

“Oh, far worse,” said the child, then burst into laughter and shouted, “Hellish!” dancing over the lawn.

“Take care, they’ll hear you, Helen.”

“Oh, booh! It’s just dirty old cashmere—serve them right. They can’t see me if they’re not here to see and so it doesn’t matter. It’s only with them I feel funny.”

“Haven’t you got to remove your finery before dinner.”

“No, because you’re here.”

“O my prophetic soul!” groaned Doctor Malcolm.

Coffee was served in the garden. The servant girl brought out some cane chairs and a rug for Boy. The children were told to go away and play.

“Leave off worrying Doctor Malcolm, Helen,” said Henry. “You mustn’t be a plague to people who are not members of your own family.” Helen pouted, and dragged over to the swing for comfort. She swung high, and thought Doctor Malcolm was a most beautiful man—and wondered if his dog had finished the plate of bones in the back yard. Decided to go and see. Slower she swung, then took a flying leap; her tight skirt caught on a nail—there was a sharp, tearing sound—quickly she glanced at the others—they had not noticed—and then at the frock—at a hole big enough to stick her hand through. She felt neither frightened nor sorry. “I’ll go and change it,” she thought.

“Helen, where are you going to?” called Anne.

“Into the house for a book.”

The old woman noticed that the child held her skirt in a peculiar way. Her petticoat string must have come untied. But she made no remark. Once in the bedroom Helen unbuttoned the frock, slipped out of it, and wondered what to do next. Hide it somewhere—she glanced all round the room—there was nowhere safe from them. Except the top of the cupboard—but even standing on a chair she could not throw so high—it fell back on top of her every time—the horrid, hateful thing. Then her eyes lighted on her school satchel hanging on the end of the bed post. Wrap it in her school pinafore—put it in the bottom of the bag with the pencil case on top. They’d never look there. She returned to the garden in the every-day dress—but forgot about the book.

“A-ah,” said Anne, smilingironically. “What a new leaf for Doctor Malcolm’s benefit! Look, Mother, Helen has changed without being told to.”

“Come here, dear, and be done up properly.”

She whispered to Helen: “Where did you leave your dress?”

“Left it on the side of the bed. Where I took it off,” sang Helen.

Doctor Malcolm was talking to Henry of the advantages derived from public school education for the sons of commercial men, but he had his eye on the scene, and watching Helen, he smelt a rat—smelt a Hamelin tribe of them.

Confusion and consternation reigned. One of the green cashmeres had disappeared—spirited off the face of the earth—during the time that Helen took it off and the children’s tea.

“Show me the exact spot,” scolded Mrs. Carsfield for the twentieth time. “Helen, tell the truth.”

“Mumma, I swear I left it on the floor.”

“Well, it’s no good swearing if it’s not there. It can’t have been stolen!”

“I did see a very funny-looking man in a white cap walking up and down the road and staring in the windows as I came up to change.” Sharply Anne eyed her daughter.

“Now,” she said. “I know you are telling lies.”

She turned to the old woman, in her voice something of pride and joyous satisfaction.

“You hear, Mother—this cock-and-bull story?”

When they were near the end of the bed Helen blushed and turned away from them. And now and again she wanted to shout “I tore it, I tore it,” and she fancied she had said it and seen their faces, just as sometimes in bed she dreamed she had got up and dressed. But as the evening wore on she grew quite careless—glad only of one thing—people had to go to sleep at night. Viciously she stared at the sun shining through the window space and making a pattern of the curtain on the bare nursery floor. And then she looked at Rose, painting a text at the nursery table with a whole egg cup full of water to herself...

Henry visited their bedroom the last thing. She heard him come creaking into their room and hid under the bedclothes. But Rose betrayed her.

“Helen’s not asleep,” piped Rose.

Henry sat by the bedside pulling his moustache.

“If it were not Sunday, Helen, I would whip you. As it is, and I must be at the office early to-morrow, I shall give you a sound smacking after tea in the evening...Do you hear me?”

She grunted.

“You love your father and mother, don’t you?”

No answer.

Rose gave Helen a dig with her foot.

“Well,” said Henry, sighing deeply, “I suppose you love Jesus?”

“Rose has scratched my leg with her toe nail,” answered Helen.

Henry strode out of the room and flung himself on to his own bed, with his outdoor boots on the starched bolster, Anne noticed, but he was too overcome for her to venture a protest. The old woman was in the bedroom too, idly combing the hairs from Anne’s brush. Henry told them the story, and was gratified to observe Anne’s tears.

“It is Rose’s turn for her toe-nails after the bath next Saturday,” commented the old woman.

In the middle of the night Henry dug his elbow into Mrs. Carsfield.

“I’ve got an idea,” he said. “Malcolm’s at the bottom of this.”

“No...how...why...where...bottom of what?”

“Those damned green dresses.”

“Wouldn’t be surprised,” she managed to articulate, thinking, “imagine his rage if I woke him up to tell him an idiotic thing like that!”

“Is Mrs. Carsfield at home,” asked Doctor Malcolm.

“No, sir, she’s out visiting,” answered the servant girl.

“Is Mr. Carsfield anywhere about?”

“Oh, no, sir, he’s never home midday.”

“Show me into the drawing-room.”

The servant girl opened the drawing-room door, cocked her eye at the doctor’s bag. She wished he would leave it in the hall—even if she could only feel the outside without opening it...But the doctor kept it in his hand.

The old woman sat in the drawing-room, a roll of knitting on her lap. Her head had fallen back—her mouth was open—she was asleep and quietly snoring. She started up at the sound of the doctor’s footsteps and straightened her cap.

“Oh, Doctor—you did, take me by surprise. I was dreaming that Henry had bought Anne five little canaries. Please sit down!”

“No, thanks. I just popped in on the chance of catching you alone...You see this bag?”

The old woman nodded.

“Now, are you any good at opening bags?”

“Well, my husband was a great traveller and once I spent a whole night in a railway train.”

“Well, have a go at opening this one.”

The old woman knelt on the floor—her fingers trembled.

“There’s nothing startling inside?” she asked.

“Well, it won’t bite exactly,” said Doctor Malcolm.

The catch sprang open—the bag yawned like a toothless mouth, and she saw, folded in its depths—green cashmere—with narrow lace on the neck and sleeves.

“Fancy that!” said the old woman mildly.

“May I take it out, Doctor?” She professed neither astonishment nor pleasure—and Malcolm felt disappointed.

“Helen’s dress,” he said, and bending towards her, raised his voice. “That young spark’s Sunday rig-out.”

“I’m not deaf, Doctor,” answered the old woman. “Yes, I thought it looked like it. I told Anne only this morning it was bound to turn up somewhere.” She shook the crumpled frock, and looked it over. “Things always do if you give them time; I’ve noticed that so often—it’s such a blessing.”

“You know Lindsay—the postman? Gastric ulcers—called there this morning...Saw this brought in by Lena, who’d got it from Helen on her way to school. Said the kid fished it out of her satchel rolled in a pinafore, and said her mother had told her to give it away because it did not fit her. When I saw the tear I understood yesterday’s ‘new leaf,’ as Mrs. Carsfield put it. Was up to the dodge in a jiffy. Got the dress—bought some stuff at Clayton’s and made my sister Bertha sew it while I had dinner. I knew what would be happening this end of the line—and I knew you’d see Helen through for the sake of getting one in at Henry.”

“How thoughtful of you, Doctor!” said the old woman. “I’ll tell Anne I found it under my dolman.”

“Yes, that’s your ticket,” said Doctor Malcolm.

“But of course Helen would have forgotten the whipping by to-morrow morning, and I’d promised her a new doll...” The old woman spoke regretfully.

Doctor Malcolm snapped his bag together.

“It’s no good talking to the old bird,” he thought, “she doesn’t take in half I say. Don’t seem to have got any forrader than doing Helen out of a doll.”

(1910)