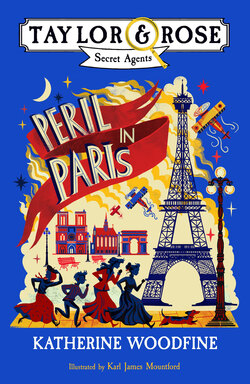

Читать книгу Peril in Paris - Katherine Woodfine - Страница 17

ОглавлениеCHAPTER SIX

Wilderstein Castle, Arnovia

Anna held her breath as she crept along the hall, towards the governess’s bedroom. It was past midnight and the castle was whisper-quiet, the passageway made strange with shadows. In the dark, the antlers of the stuffed animal heads on the wall, the rusting suit of armour, even the painted shield with the arms of the Royal House of Wilderstein seemed to shift into new and sinister shapes.

A long, thin crack of yellow light was visible at the bedroom door and Anna moved towards it, her bare feet soft on the chilly stone flags. She felt excited. She knew that she was not supposed to be out of bed late at night, creeping around the castle, but it was rather thrilling to be slipping along the passageway in the dark in her nightgown, without even her bedroom slippers. It was absolutely the kind of thing that the heroines of the Fourth Form would do, even if it meant breaking the rules.

There were certainly plenty of rules at Wilderstein Castle. The Countess’s favourite words were discipline and decorum, and each day was the same, following an exact pattern. The day began with the ringing of the gong for breakfast at eight o’clock sharp, and ended with the chime of the bedtime bell, which meant that Alex and Anna must go to bed. Sometimes Anna felt that she was no more than a tiny cog in the Countess’s giant machine: a kind of musical box, where the Countess turned the handle, and spinning on top in time to the music was Alex. Not the real Alex she knew, but the Alex who would one day become King, shining out light like a golden star.

They all moved in time to the Countess’s tune: even the Count was bound by her strict timetable. Left to his own devices, Anna knew he would have been quite happy pottering about the castle, tinkering with his latest hobby – butterfly collecting, or motor cars, or more recently, his new-found passion for flying machines. Instead, the Countess insisted that each day at precisely the same time, the Count took Alex into the castle grounds for what they called ‘drills’ – a series of physical exercises inspired by his army training, which Alex simply loathed. This would be followed by a discussion of weapons and military strategy; the Count would give a detailed explanation of battle manoeuvres, or test Alex to see if he could correctly distinguish between a sabre and an épee. Alex, who couldn’t care less about broadswords and battle-axes, would return to the schoolroom pink-faced and wheezing, whilst the Count hurried back to his workshop to pore over the plans of aeroplanes.

Meanwhile, Anna’s morning always began with time at the back-board to improve her posture, whilst the Countess lectured her on royal etiquette and the importance of decorum. ‘As the Princess of Arnovia, you are an ambassador for your country and the House of Wilderstein wherever you go,’ she proclaimed. ‘You must never forget that.’ The Countess had many such maxims, most of which were about what princesses did and did not do: Princesses do not run. Princesses do not slam doors. A princess should not be inquisitive. Princesses do not lose their temper. A princess must never raise her voice. Now, Anna added in her head: A princess should not sneak about the castle at night in order to spy on her governess.

One of the many things that had struck her as odd about Miss Carter was her lack of interest in rules and discipline, and what princesses did or did not do. She had no sort of a timetable: one morning she’d let them read poetry aloud, the next she’d take them into the grounds for what she called a ‘nature ramble’. She hardly ever scolded them, except when she heard them speaking German. Then: ‘In English, please!’ she’d say at once. That made sense, Anna thought, for Miss Carter was supposed to be preparing Alex for his English school. And anyway, neither of them really minded speaking English. Although most Arnovian people spoke German, they usually spoke at least one other language as well, and Grandfather had always especially liked Anna and Alex to speak English, because of the strong relationship between Arnovia and Britain, and because their own grandmother had been an English princess. What was strange though was that Miss Carter barely ever spoke a word of German herself, except for the occasional bitte or danke. Anna had heard the Countess say that Miss Carter was fluent in several languages, but when Bianca, the Countess’s Italian maid, had tried to talk to her about some laundry, Anna had been certain she didn’t have any idea what Bianca had said.

It was yet another puzzling thing for Anna to add to her list. She was certain that the governess was up to something, and that was why she was here, creeping towards her bedroom door at night.

Some people might have thought twice about spying, but Anna didn’t. She liked to know things, and she had a talent for finding things out, especially the things she wasn’t really supposed to know. She was the one who had discovered the old secret passage in the castle cellars that no one else knew about; and she was the one who had found out about the secret love affair going on between Bianca and the Count’s valet. She had an uncomfortable suspicion that the heroines of the Fourth Form might have thought this kind of thing ‘sneaking’ or ‘dishonourable’, but she pushed that thought away as she peeped, feeling rather thrilled, through the door into Miss Carter’s bedroom.

Like many of the rooms in Wilderstein Castle, the governess’s bedroom was quite bare and cold. The stone walls were hung with crossed swords and tapestries of hunting or battle scenes – wild pigs being gored with pikes, and people in helmets hitting each other with swords. Miss Carter did not look like she belonged at all, sitting beneath one of the tapestries, writing a letter. The governess seemed quite different in a dressing gown, with her hair falling loose over her shoulders in long, snaking curls. She was not wearing her spectacles again, Anna realised, stepping a little closer, hardly daring to breathe.

She watched intently as Miss Carter put down her pen, tucked her letter into an envelope, and then got up and went over to the bed. Anna expected to see her turn back the covers, but instead, she bent down and reached under the bed, drawing something out from beneath it. Anna saw that it was a small leather attaché case, rather battered and stuck all over with luggage labels. As she watched, Miss Carter unlocked the case with a little key which hung on a chain around her neck.

Anna leaned forward, eager to see what was inside, but to her enormous annoyance, she could see only the back of Miss Carter’s head. The governess was taking something out of the case – a small object, which she dropped into her dressing-gown pocket. Then she locked the case, pushed it back underneath the bed, and made for the door.

Almost tripping over her nightgown in her haste, Anna scrambled back down the passage. From a safe spot behind the rusting suit of armour, she watched breathlessly as Miss Carter padded out of her room and down the hallway. Where on earth was she going at this time of night? She hurried silently after her, feeling more thrilled than ever. To her astonishment, she saw the governess’s dark figure approach the door of the Count and Countess’s sitting room, and then go swiftly inside.

Anna scampered quickly down the hall, creeping as close to the sitting-room door as she dared. The door had been left ajar: inside, the room was quite dark, but Miss Carter had lit a small lamp, and as Anna peered in, she saw that it had cast out a circle of light, illuminating her like an actress on a stage.

As Anna watched, she saw Miss Carter open the Count’s desk, and begin rifling through his letters and papers. The governess’s lips were moving as though she was muttering to herself, though Anna couldn’t hear what she was saying. After a few moments she took out a single sheet of paper, and laid it flat on the desk under the light.

Anna stared and stared as the governess took out the object she’d dropped into her dressing-gown pocket. It was small and round, and looked rather like a silver watch. But as Anna watched, she held it close to the paper. There was a loud, distinct click. Miss Carter wound the watch and held it out again. Click went the watch, the mechanism loud in the night. Except it wasn’t a watch at all, Anna realised. It was a camera. The governess was photographing private papers from inside the Count’s desk!

She let out a little gasp of surprise, and Miss Carter looked up sharply. She couldn’t see Anna standing in the dark of the hallway, but at once she turned out the lamp, plunging the room into blackness. Frightened now, Anna darted as quickly as she could back along the passageway. But before she could reach the safety of her room, she collided with someone coming the other way, someone tall and solid. She looked up in alarm to see that she’d slammed into a footman, a new one, whom she’d never spoken to before. He looked down at her with an unpleasant sneer on his face.

‘Why are you here, running about in the dark?’ he hissed. ‘You ought to be more careful by yourself at night, Princess.’

Anna stepped back at once, alarmed. Footmen never spoke to her like that – they always bowed respectfully and addressed her as ‘Your Highness’. They certainly would never say ‘Princess’ in that contemptuous way. She was so surprised she couldn’t say a word: meanwhile, the footman only gave a mocking little snigger.

Just then, to Anna’s enormous relief, Karl appeared around a corner. ‘Your Highness! What are you doing out of bed in the cold, and without any bedroom slippers? Whatever would Her Ladyship say?’ he clucked. He gave the new footman a doubtful look. ‘You can go – I’ll take care of Her Highness,’ he informed him. Then, more reassuringly to Anna: ‘Come along. Back into bed for you.’

But even when Karl had brought Anna back to her own bedroom, and she was tucked up safely in her own bed again, sleep felt very far away. There was no doubt about it, she thought as she lay wide awake in the dark. There were strange things happening at Wilderstein Castle. Strangest of all, she was now quite sure that the new English governess was a spy.