Читать книгу Asylum on the Hill - Katherine Ziff - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеPREFACE

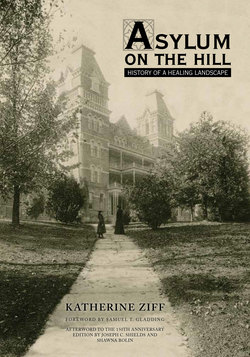

In 1867 the Ohio legislature laid the foundation for a twenty-year experiment in moral treatment psychiatry at Athens, a small village in the rural southeastern corner of the state. Built to American psychiatry’s nineteenth-century gold standard, the Kirkbride plan for moral treatment, the Athens Lunatic Asylum proposed to cure its patients with orderly routines, beautiful views of the countryside, exposure to the arts, a built environment with abundant natural light and plenty of ventilation, outdoor exercise, useful occupation, and personal attention from a physician. Its restorative landscape and efforts to offer humane treatment were a revolution in care for those with mental illness and stand in contrast to hundreds of years of treatment featuring confinement, restraint, and punishment. Nearly a century and a half later, the asylum is making new history as one of the most fully realized examples of the repurposing of old Kirkbride buildings into a university and community resource.

I moved to Athens, Ohio, in 1998. On the first day of my first visit to town, I walked with my son over to The Ridges, the new name for the complex of buildings and landscape that were once the Athens Lunatic Asylum. As we climbed the steep hill to watch bicycle racers rattle over the brick drive around the old asylum buildings, my first impression was of trees. To reach the imposing brick buildings, we walked through a small grove of towering evergreens, remnants of the original landscape planted more than a century ago by landscape gardener George Link and the group of asylum patients who served as his work crew. The buildings and their grounds sit on top of a long and substantial terrace flanking the Hocking River, formed two million years ago in a collision of geology and climate change in southeastern Ohio. If you drive down Route 33 from Columbus, Ohio, toward Athens, just after you pass through Lancaster you will see, as we say in southeastern Ohio, “where the glacier stopped.” There the flat terrain gives way to gentle hills that become steeper as you get to Athens, following Highway 33, which crosses the Hocking River twice. As rivers go, the Hocking is relatively young, created as glaciers dammed and then drained the ancient and massive Teays River of central North America. The river’s terraces, ninety feet above the present-day riverbed, were formed by the geologic rubble of glacial outwash pushed into the Hocking and deposited downstream alongside the river. Two thousand years ago on the terrace on which The Ridges is located, the Adena built burial mounds deeply imbued with religious, emotional, and psychological meaning.1 Nearly two millennia later on this site were established the hopes for a healthy, harmonious therapeutic community dedicated to healing persons with mental illness. Ohio University is now the steward of over seven hundred acres of this landscape. Part of the complex originally named the Athens Lunatic Asylum, the land supported the asylum’s dairy, orchards, park, lakes, greenhouses, kitchen gardens, piggery, and herds of cattle.

The asylum at Athens was deeply connected with nineteenth-century America’s far-reaching demographic changes. With postwar industrialization, the movement of a large proportion of the population to cities, and the decline of an agrarian economy, asylums were expected to serve a humanitarian function and provide a measure of community stability. The pain and suffering endured by Americans in the Civil War inevitably were exhibited in the lives of its survivors: soldiers and their families who were hospitalized in asylums for trauma and grief. In addition, the grim economic times of the Long Depression of 1873–79 triggered mental health crises. All of these dynamics were features of the asylum at Athens. A scholarly discussion about America’s two-hundred-year history of asylums has centered on this question: were asylums built to serve communities and preserve social norms or to provide humanitarian care to individuals with mental illness? The truth is that American asylums, including the one at Athens, served both the humanitarian needs of individuals and the social needs of community structures.2 The Athens asylum, in its moral treatment years, admitted thousands of patients for a wide array of reasons, from a coal miner who was committed for seeking to organize his fellow workers into a labor union to persons who had made attempts to kill themselves and their families to women in need of respite care after childbirth.

A central strand of the moral treatment practiced for twenty years at Athens, as well as in asylums across the United States, is therapeutic place, or the healing properties of a landscape, whether a natural geography or one intentionally shaped.3 The landscape designer for the Athens asylum, gardener Herman Haerlin of Cincinnati, worked in the nineteenth-century tradition of landscaping pioneered in America by Frederick Law Olmsted: creating a natural wildness that would calm the mind and soothe the soul.4 The idea of therapeutic, or restorative, landscape has been around for millennia, from at least the time of Asclepius and the Asclepian healing temples built in ancient Greece high above the sea on cliffs and bluffs affording beautiful views.5 Known also as restorative gardens, therapeutic landscapes have reemerged from time to time, notably in medieval monastic gardens such as that of Bernard of Clairvaux at the hospice of his French monastery.6 Today in the twenty-first century, the strand has emerged again, flourishing this time along with treatment modalities grounded in nineteenth-century moral treatment and reconceived with new names and disciplines such as wilderness therapy, milieu therapy, creative arts therapies, humanistic psychology, and restorative gardening.7

If you take a walk on the dirt roads and paths through the old fields around the Athens Lunatic Asylum buildings today, you will see great drifts of milkweed, Asclepius syriaca, a symbolic reminder of the roots of the moral treatment experiment at the Athens Lunatic Asylum. In early summer these tall plants nod with round magenta flower heads, which in August swell into pale green pods that by winter have dried and burst, releasing thousands of seeds that float on silky white threads. They evoke Asclepius, the healer of ancient Greece, who was taking up his work about the time that the Adena were using the grounds of the site of the Athens asylum for sacred purposes.

The research for this book was approved by the Ohio Department of Mental Health, which provided me with access to a wealth of nineteenth-century medical records, including patient commitment documents, the original 1874 medical logs, and files of the writings of patients and their families. I have had the privilege of reading thousands of patient case files and present here those illustrating the conditions and themes underlying the commitment of individuals to the asylum at Athens between 1874 and 1893. Although ultimately doomed by overcrowding and overshadowed by the rise of new models of care, for twenty years the therapeutic community at Athens pursued moral treatment therapy with energy and optimism.

The asylum has been known by eleven different names since it opened in 1874:

TABLE P.1

Names for the institution since its founding

Athens Lunatic Asylum, the name under which it opened, is the one used throughout this work. In 1993, the asylum closed and moved to a new and much smaller building directly across the river on its northern banks.8 The chapters of this book illustrate the moral treatment era (1874–93) at the Athens Lunatic Asylum through stories of tragedy, politics, confusion, struggle, and hope. Drawing upon case histories, medical notes, commitment documents, letters, and reports, each chapter illustrates a facet of the moral treatment experiment at the Athens Lunatic Asylum, including its patients, architecture, politics, therapeutic landscape, and caregivers.