Читать книгу The Prostitution of Sexuality - Kathleen Barry - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Introduction

ОглавлениеSexual exploitation objectifies women by reducing them to sex; sex that incites violence against women and that reduces women to commodities for market exchange. Sexual exploitation is the foundation of women’s oppression socially normalized. This is a difficult and painful subject to study. I tried to back away from this painfulness when I wrote Female Sexual Slavery. I said then:

When a friend first suggested that I write a book on what I was describing to her as female sexual slavery, I resisted the idea. I had gone through the shock and horror of learning about it in the late 1960s when I discovered a few paternalistically written books documenting present-day practices. During that same period I found a biography of Josephine Butler, who single-handedly raised a national and then international movement against forced prostitution in the nineteenth century but who is now virtually unknown. I realized that Josephine Butler’s current obscurity was directly connected to the invisibility of sex slavery today. And so I wrote a few short pieces on the subject and incorporated my limited information into the curriculum of the women’s studies classes that I taught.

But to write a book on the subject—to spend 2 or 3 years researching, studying female slavery—that was out of the question. I instinctively withdrew from the suggestion; I couldn’t face that. But as the idea settled over the next few weeks, I realized that my reaction was typical of women’s response: even with some knowledge of the facts, I was moving from fear to paralysis to hiding. It was then that I realized, both for myself personally and for all the rest of us, that the only way we can come out of hiding, break through our paralyzing defenses, is to know the full extent of sexual violence and domination of women. It is knowledge from which we have pulled back, as well as knowledge that has been withheld from us. In knowing, in facing directly, we can learn how to chart our course out of this oppression, by envisioning and creating a world which will preclude female sexual slavery. In knowing the extent of our oppression we will have to discover some of the ways to begin immediately breaking the deadly cycle of fear, denial-through-hiding, and slavery.

Far from being the project I feared facing, the research, study, and writing of this book [Female Sexual Slavery] have given me knowledge that forces me to think beyond confinement of women’s oppression. Understanding the scope and depth of female sexual slavery makes it intolerable to passively live with it any longer. I had to realistically visualize a world that would preclude this enslavement by projecting some ways out of it. Reading about sexual slavery makes hope and vision necessary.

That was 1979.

Because I found it painful to write about this fact of women’s lives, for the next decade, the 1980s, I tried to shift some of my work into other areas. In 1980, just after my book Female Sexual Slavery was published, I conducted meetings on this issue at the 1980 Mid—Decade of Women Conference in Copenhagen, from which came an international feminist meeting held in Rotterdam in 1983. I am grateful to Barbara Good for her networking that led now Senator Barbara Mikulski to initiate a resolution we drafted on prostitution that was adopted in the 1980 U.N. Conference in Copenhagen, a significant boost to this work. But launching international feminist political action to confront sexual exploitation also brought out the proprostitution lobby—organizations and individuals who actively promote prostitution—who made me and my lectures the focus of their attack and disruption and hate campaigns for several years.

I returned to the United States to find that our own feminist movement against pornography which I was part of launching in the 1970s had escalated with the most important legal approach to have come out of our movement to that point, the feminist civil rights antipornography law, “the Dworkin-MacKinnon Ordinance,” as we have come to call it. Political radical feminism more and more was directing its energies to the struggle against pornography, challenging sexual liberals and just plain liberals for their promotion of sexual abuse and exploitation. This brought out the “sexual outlaws”; lesbian sadomasochists and heterosexual women hiding behind their private pornographic sexual lives joined forces to form the “Feminist” Anti-Censorship Task Force. Radical feminism was under siege as it had been a century earlier. We barely noticed the shift that was occurring in the women’s movement, the shift to a one-issue movement. We had already learned that single-issue movements do not survive because they are disconnected from the totality of women’s oppression.

I found myself in the ironic position of building an international movement only to come home to my own movement to find I was out there alone on the issue of female sexual slavery. I lectured on prostitution as a condition of sexual exploitation. But it was treated by the movement as an “add-on,” an issue tacked on to the work against pornography or sexual violence simply to be sure that all the bases were covered.

After organizing an international meeting in Rotterdam on female sexual slavery in 1983, exhausted and depressed from repeated undermining and personal attack on my radical feminism by the proprostitution lobby and by Western liberals there, I announced to several feminist friends including Robin Morgan, whose support has been more than sustaining, that I had gone as far as I could on this issue. I explained that even after organizing an international meeting, I was still alone and I was withdrawing. But they had other plans. They were excited about how the international network I had been developing could begin a new wave of NGOs, nongovernmental organizations in consultative status with the United Nations. (I actually moaned aloud in the restaurant when Robin proposed this over dinner.) Having worked with many human-rights NGOs internationally, I could see the potential for global feminist consciousness raising. The international networking I had been developing on the issue of traffic in women would qualify our coalition for human rights (Category II) status with the United Nations.

However, I rejected then, as I do now, the idea of a one-woman movement. Although I could no longer be out there alone on this issue, especially among women from the West, I reluctantly initiated the application to the United Nations for NGO status. That work, along with demands for lectures and actions organized on behalf of victims, kept me going despite my personal decisions and even despite the toll it began to take on my health, not to mention the extreme costs to my professional career.

At last, by the mid 1980s something had changed. In the United States Evelina Giobbe announced the organization of WHISPER (Women Hurt in Systems of Prostitution Engaged in Revolt). Then Susan Hunter organized the Council for Prostitution Alternatives.

In the Asian region in particular women have mounted massive campaigns against sex industries and their consumers. I have had the privilege of working with dedicated women like Aurora Javate DeDios and the Philippines Organizing Team, Yayori Matsui in Japan, Jean D’Cunha in India, and Sigma Huda in Bangladesh who have brought deeply felt and powerful analysis to the issue of sexual exploitation of Asian women.

In 1987 I decided it was time, once and for all, to move on to other issues. At the New York Conference on Sexual Liberals and the Attack Against Feminism, I gave the issue back to our movement, challenging the audience of 1,500 feminists not to let this work on prostitution and traffic in women be reduced to a one-woman movement. I asked them to take up the issue, and I added emphatically, “do not call me.” And no one did for almost a year. What I did not know was that during that time Dorchen Leidholdt, who had organized the 1987 conference and had been spearheading radical feminist actions through Women Against Pornography, had indeed taken up the issue. She and a group of women were organizing an international conference on traffic in women in 1988. Calls from Dorchen for information and clarification drew me back from my short hiatus, but this time things were different. From international feminism we launched The Coalition Against Trafficking in Women, organized based on my original work, Female Sexual Slavery, first published in 1979. By then the international work against traffic in women had become a feminist movement.

As we worked together and gained nongovernmental status with the United Nations, we found new avenues for addressing women’s human rights. In 1986 I had been a rapporteur in a UNESCO meeting of experts on prostitution held in Madrid. In that meeting it was clear to me that present U.N. conventions could no longer address the problems of sexual exploitation. I remember telling Wassyla Tamzali in the Division of Human Rights and Peace Rights at UNESCO that that five-day meeting was the first time since I wrote Female Sexual Slavery that I had been challenged into new analysis of this issue. Seven years was a long time to wait. Those new ideas led to a collaboration with UNESCO in a meeting I held at Penn State in the spring of 1991, which has led to the development of a new model for an international human rights law, the Convention Against Sexual Exploitation. Such momentum internationally and with feminists in the United States in 1992 formed the basis of a Plan of Action for networking on the part of the Coalition Against Trafficking in Women and UNESCO. The plan as Wassyla Tamzali and I developed it called for joint action to create an international network to confront sexual exploitation, especially in prostitution as a violation of women’s human rights. The work and support of Twiss Butler and Marie Jose Regab, of the National Organization for Women has provided encouragement and networking.

Despite the overwhelming prostitution of women’s sexuality, the unbridled trafficking in women worldwide, and the sex-industry-supported proprostitution lobby, I have seen many important changes since the mid 1970s when I was researching and writing Female Sexual Slavery. Back then, prostitution and traffic in women were as disconnected from the women’s movement as they were silenced. In Europe Denise Pouillon Falco, Renée Bridel, Suzanne Képés, and Anima Basak sustained long-standing movements and actions on this issue when it was silenced elsewhere. They provided hope, support, and friendship. But in research, prostitution, treated as a form of female deviance and an area of criminology, was considered inevitable but controllable. Traffic in women had been made invisible after the campaigns of Josephine Butler in the nineteenth century. But in 1986 sitting in a conference organized by Cookie Teer in North Carolina when Evelina Giobbe described her new organization WHISPER, with tears in my eyes, I realized that it had all been worth it.

In the beginning of our women’s movement, in the late 1960s and early 1970s, in thirst of our history and in search of our theories, we voraciously read of our feminist past. We were struck by the most glaring political mistake of our foremothers—an error not at all evident to them during the first wave of feminism. After more than 20 years of radical feminist struggle against the widest and deepest range of exploitations and violations against women, that first wave of the U.S. women’s movement made the tactical error of focusing primarily on one issue above all others—suffrage. The reasoning was sound, the practicality clear: that without political power women would not be able to gain for themselves their other demands.

But that strategic shift, from radical feminist confrontation against oppression to single-issue movements emphasizing legalistic reform, was the beginning of the end. By the time women achieved their goal of suffrage, the women’s movement had died. It would take at least another 70 years for women to use their vote for women.

Twenty-five years ago, launching this second wave of the movement, we radical feminists promised ourselves that we would never, ever concede our radical movement by reducing it to a single strategy, that we would never retreat from the interconnections among all issues confronting women. To do so would be to concede our revolution and reduce our struggle to individual personalities and to legal reform. But it has happened.

Not only have issues of sexual exploitation been reduced to a single-issue movement; they have been configured only (or at least primarily) in terms of legal change. But patriarchy will never make itself illegal. Long before new laws are enacted or ever actually protect women, the struggle for them is where and when feminists set new standards. Our struggle must go beyond law and reform to their roots in the experience of female oppression. I consider legal change to be an important aspect of our movement and struggle. That is why since the beginning I have supported and promoted the civil rights antipornography legal proposals, and I have promoted the development of new international law. But law, attractive as it is to a captivated American audience, is only one part of radical change. What ultimately matters is that male behavior change.

In the 1990s we have found that in the United States women’s issues have become so dissociated from each other that there are separate movements for abortion rights under the euphemism of “choice” while at the same time the euphemism “choice” is turned into the rallying call for the promotion of sexual exploitation through pornography and prostitution as fostered by sexual liberals and the proprostitution lobby, who ask, don’t women “choose” prostitution? pornography? (as if this question made an ounce of difference to the customer-, i.e., male-driven market). Meanwhile our movement has become so deconstructed that issues like teenage pregnancy and prochoice, which means girls’ right to abortion, are dissociated from the very conditions that have produced a crisis in teenage pregnancy: sexual exploitation—the wholesale sexualization of society and promotion of early sex through pornography and the legitimization of prostitution.

Feminist programs have suffered with the fragmentation of issues. There has been the reduction of some feminist programs we launched, such as rape-crisis programs initiated in the early 1970s to social-work programs of the 1980s. This has further deconstructed the political commitment of feminism to revolutionary change. And consequent to this, we radical feminists have been isolated, made into targets of the sexual liberals and proprostitution lobby because we insist on confronting sexual exploitation as a condition of oppression.

How did pornography come to be taken up as a feminist action dissociated from other issues—especially prostitution, especially rape, especially sexual harassment? As feminist political action against pornography escalated, it separated into a particular movement of its own. The separation was forced, in large part, by the attacks from sexual liberals. In this near-deadly struggle, radical feminism began to turn more and more exclusively to anti-pornography because we were embattled and fighting to survive, as was true with Susan B. Anthony when she desperately turned to focus on a single issue, suffrage, in the nineteenth century.

The civil rights, anti-pornography ordinance developed by Andrea Dworkin and Catharine MacKinnon defined pornography as “sexually explicit subordination of women.” This definition was a key to inclusiveness, to widening the girth of the movement, for it refers to a collective female class condition. Oppression. Domination. And so revolutionary struggle has been inherent in this anti-pornography work, even if the movement has lost focus on the fullest, widest range of issues and, most importantly, their interconnections—for it is in their interconnections that we find revealed the complex web of patriarchal domination of women as a class. The history of feminism is a warning to us against turning from one single issue to the next. When we open up a “new” issue, last year’s issue goes to therapy or social work—possibly important but apolitically individualized.

When in the second half of the 1970s I was writing Female Sexual Slavery, I did not consider that I was writing a book on prostitution. Nor, as I’ve already established, was I trying to break open the next “new” feminist issue. My effort then and since has been to integrate the violation of women by prostitution into the feminist struggle and to move it, as one of several connected issues, into the forefront of the feminist agenda. I have approached this struggle by understanding prostitute women not as a group set apart, which is a misogynist construction, but as women whose experience of sexual exploitation is consonant with that of all women’s experience of sexual exploitation.

What I was doing in Female Sexual Slavery was writing about the use of sex/sexuality as power—to dominate—as a condition of oppression. I am concerned with a class condition. My study of sex as power then and now inevitably, continually, unrelentingly returns me to prostitution. I knew then that one cannot mobilize against a class condition of oppression unless one knows its fullest dimensions. Thus my work has been to study and expose sexual power in its most severe, global, institutionalized, and crystallized forms. I reasoned that we could know the parts because we would know the whole. From 1970 I had been involved in initiating radical feminist action against rape, but until I learned of the traffic in women and explored the pimping strategies in prostitution, I did not fully grasp how utterly without value female life is under male domination. Women as expendables. Women as throwaways. Prostitution—the cornerstone of all sexual exploitation.

To confront the whole, the female class condition, strategically and politically, I launched action in an international arena of human rights because sex is power over all women. As the female condition is a class condition, sex power must be addressed as a global issue, inclusive of all of its occurrences in the subordination of women. To do that prostitution must be centered in this struggle.

I have chosen to focus my militancy and strategizing against oppression on human rights. While promoting individual civil rights, I believe that human rights can be taken further. Expanded to the human condition, it has been used to recognize that peoples—such as those under apartheid, and those under any form of colonization—have a right to self-determination. The appeal of human rights to me is its ability to protect the class, collective condition—and this is a protection not yet available to women. However, the decolonization of the sexually exploited female class has not yet begun. In 1970 I participated in issuing the Fourth World Manifesto, written in response to socialists who tried to coopt the women’s movement to serve the left as if men were not imperialists of sex. In that manifesto we established the colonization of women as a condition of patriarchy. Where the United Nations will protect the “sovereign [read independent] rights of all peoples and their territorial integrity,”1 in our present human rights work, I intend to see that women, as a territory sexually colonized, are granted that protection. With the struggle of our movement, we will one day see to it that, according to U.N. human-rights standards established for other groups, sexual exploitation is treated as a class condition that is a crime against humanity as much as it is a crime against any individual human being.

Thus, in studying sex as power in Female Sexual Slavery, I found the class condition of all women to be fully revealed in prostitution. That finding led me into almost two decades of work on developing an international human-rights approach to confronting that class condition globally.

But to get to that point in our struggle we must go back to the original premise of radical political feminism: that the personal is political and therefore, the separation of them—the “whores”—and us—the “women”—is utterly false, a patriarchal lie. And that means that we must talk about sex. The sexuality of today. Not only in pornography. Not only when it is explicitly “against our will.”

In this work, I am shifting from my previous work on the sexuality of prostitution to my new work on the prostitution of sexuality. I am taking prostitution as the model, the most extreme and most crystallized form of all sexual exploitation. Sexual exploitation is a political condition, the foundation of women’s subordination and the base from which discrimination against women is constructed and enacted.

The feminist international approach of this study recognizes that there are worldwide commonalities to women’s subordination and that therefore there must be a commonality to power arrangements across races, classes, and state boundaries. The word “gender,” intended by feminists to refer to the social basis of sex ascription and thus to reveal sexual politics, has been neutralized by academics so that it now simply refers to biological differences between the sexes. “Gender” has become an apolitical term, a word that makes it possible to not have to specifically designate “woman.” “Gender” makes patriarchy, the historical and political context of power, disappear. That is the context in which female sexuality is prostituted worldwide today in order to secure the domination of women.

The facts of women’s subordination and patriarchy do not disappear because language is depoliticized and neutralized. In this work I am studying prostitution as institutionalized and industrialized sexual exploitation of women, developed from patriarchal feudalism. Theoretically, I have developed a macro-level analysis of the global condition of women that is lodged in the micro-level analysis of human interaction and personal experience. Sociologically, this work explores sexual exploitation by bridging the “macro-micro” gap, which has been noted as a problem whenever research is confined to one level or the other. From a feminist perspective, this is the bridge from the personal to the political. It recognizes that sexual exploitation is a condition that includes all women in prostitution. As prostitution has become industrialized and a global economy has come to shape international relations, it is more important than ever to feminist research and activism that these different levels of analysis be joined.

For the study of prostitution, traditional measures are not available. Beyond general estimates of prostitution populations, there are no reliable statistics on prostitution because it is by and large illegal. Even where prostitution is legalized, greater percentages of it remain illegal, and it is controlled by organized crime and therefore inaccessible for measurement. And prostitute women are not counted in the development of demographic data and trends in research on women in development.

The most reliable knowledge and documentation of trafficking in women and children come primarily from three sources: (i) human-rights organizations, which are primarily concerned with children and operate from a distinction between “free” and “forced” prostitution in a context of severe poverty, (2) AIDS activists, researchers, and foundations who in the last 5 years have begun to address prostitution, considering it central to the spread of AIDS and being concerned with it from that standpoint, and (3) feminist organizations concerned with women’s rights and human rights, which address the concerns of the other two groups in their particular focus on women. Only feminist/human-rights organizations and activists are addressing the full range of conditions that promote trafficking and sex industrialization because only they are concerned with women (and therefore children and AIDS and poverty). Therefore, research on this subject draws both from first-hand observations and from the documentation and statistics produced primarily by these groups. In the case of prostitution, sex trafficking, and sex industrialization, the reports, statistics, and estimates from state governments are the least reliable. Frequently, local police and border guards are either involved in the trafficking or taking bribes. In fact, some national government officials have made the point that human-rights workers give the government a bad name by exposing cases of trafficking.

A combination of qualitative methods is the best approach to exposing practices that are otherwise inaccessible, especially because they sustain exploitation.2 The approaches I have taken to the study of sexual exploitation are

1. to document the dimensions of prostitution and traffic in women globally and to trace them historically in order to identify macro/global patterns and trends and to determine the impact of the West and its global economic dominance on the developing world;

2. to adopt a symbolic-interaction approach to interpretation in studying the individual experience of sexual exploitation, particularly prostitution;

3. to analyze the interaction of the macro/global condition with micro-individual/interactive experience in terms of international human-rights law, and to identify projects and programs that did not exist when I was writing Female Sexual Slavery but that now are some of the best examples of success in confronting sexual exploitation, particularly in prostitution; and

4. theoretically to consider sexual exploitation as a condition of oppression in terms of sexual relations of power.

Adopting global, theoretical, individual/interpretive, and programmatic-policy and legal approaches, one could argue, is too large an undertaking. Surely such a work risks overgeneralization. However, because sexuality has not been dealt with comprehensively but rather is typically disaggregated in sexological and criminological research, an overall study of the interlocking forces of male domination is required in order to locate women in prostitution within the class conditions of women under patriarchal domination. In order not to reduce women in prostitution and women who are subjected to the prostitution of sexuality to biologically sexed beings or to deviants and criminals, it is necessary to risk some overgeneralization in the process of bringing together the forces that shape sexual exploitation of women today.

My research in this book has developed over two decades. During that time, through my work with women on all the continents, I have had repeated opportunities to present my analysis, confirm my findings, and reassess my assumptions so as to achieve their present refinements. In order to study global macro trends in the absence of concrete statistical data, I have turned to a variety of sources: my own original research in documenting specific cases of female sexual slavery, as well as cases documented and brought before the United Nations, court proceedings, and newspaper accounts. Through the international network and the number of international meetings I have organized, I have been able to confirm cases. From many divergent sources, I have drawn together a range of material that has made it possible to identify new patterns and practices.

To study the interactional effects of the individual experiences of sexual exploitation, I have drawn from my own interviews with prostitute women that began in 1977 and have continued as I have worked with women in different world regions. With these interviews and those from recent research, I explore the interactive dimensions of sexual exploitation.

Symbolic interaction is the study of the interpretation of gestures in human interaction.3 It posits that in interpreting the meaning of the other, we approximate our understanding of the other’s meaning by putting ourselves in the place of the person with whom we are interacting. Not only does symbolic interaction provide an intense approach to the interpretation of meaning of subjects in experience; for me it also establishes the point of view of the researcher.

For the researcher in symbolic interaction, the meaning of a situation is derived by interpreting that meaning from the point of view of the person in the situation. That is, all that is taken in by the persons engaged in interpreting each other’s gestures constitutes the interpretation and the situation. Interpretation is then what produces social reality and is the source of social facts.4 For the feminist researcher studying women’s experiences that are violations of human rights, one step further is required in order effectively to interpret interaction. Engagement with one’s subject involves taking on the meaning of the other by putting oneself in her place, by asking “What would I have done?” and “What meaning would I have interpreted if I were in that situation?” This feminist approach, combined with symbolic interaction, is what makes it possible to break the silences surrounding sexual exploitation.

As a research approach, the significance of symbolic interaction is that it is neither intraindividual nor deterministic. It recognizes not only that interaction takes place in a situation (what some psychologists prefer to call “context”) but also that interaction is the situation. It is the part and it is the whole. To conduct research from this approach it is necessary to reconstruct the situations of sexual exploitation in order to determine their meaning—meaning that is both individual and social. The situations are both the interpretative interaction and all that surrounds the individuals, including the individuals that are taken into account in the interpretation. But the situation in which interpretation takes place stretches far beyond the immediacy of interaction to include the geographic, economic, and political landscape from which meaning is drawn in interpretation. Therefore, global conditions and private life intersect in interpretation. In analyzing conditions of sexual exploitation, this is how macro and micro are brought together. In this sense interpretation produces social facts that are neither reducible to the individual, nor to intraindividual phenomena, nor to dissociated personal interaction.

Some things stay the same as much as they change and that is why I began this work only as a revision of Female Sexual Slavery. But two years into the “revisions” I was back to doing original research and developing new theory. Revision proved to be an impossible project because too much has changed since 1979. I am grateful to Donna Ballock and Brenda Seery for assistance with entering revisions into the manuscript and for their willingness to do that over and over again long after I would declare that I had finished but I had not. I deeply appreciate Rosemary Gido’s reading of earlier drafts, Polly Connelly’s reading of the final manuscript, and Colin Jones, Director of New York University Press for his suggestions and patience with the rewrites.

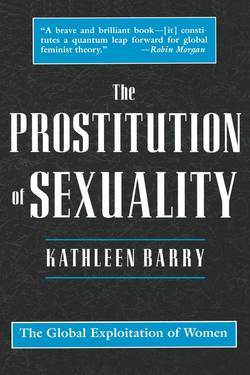

Prostitution of Sexuality, as the title of the work reveals, indicates the direction of the changes in prostitution toward its normalization in nonprostitute sexual exchanges. This book presents new theory and analysis that explore in depth the effects of prostitution on women and the implication for women’s human rights. All that remains in this work from the original Female Sexual Slavery are some of the original cases and analysis that I have included now for the purpose of comparison with the present situation. I have documented the major practices in trafficking today and left those cases from the earlier work that reflect the connections and comparisons between trafficking then and now. Moreover, it is now possible politically to theorize about this issue beyond the ways that were just beginning to be possible in the 1970s.

Prostitution and sexual exploitation have grown dramatically and changed significantly since I wrote Female Sexual Slavery. As I compared then with now, the Prostitution of Sexuality, much more than a revision of Female Sexual Slavery, became a new work. As I sifted through the new knowledge we have gained, the revisions became rewrites and eventually new chapters. Through the meetings, work, organizing, and campaigning of the 1980s and the 1990s with feminists around the world and within the United Nations and UNESCO, my theories and analysis have grown, changed, and developed. This has led to entirely new chapters on “Prostitution of Sexuality,” “Sexual Power,” “Industrialization of Sex,” “Traffic in Women,” and “Human Rights and Global Feminist Action.”

I have retained my historical study of Josephine Butler, who, for decades, has been a model for me. However, today I probably understand better why. Her passionate commitment to fighting state-regulated prostitution was deeply connected to her direct work with women victimized by it. When I first wrote Female Sexual Slavery, I was particularly concerned to give a feminist-historical base to this work and to analyze her struggle against regulated prostitution. In the last decade, as the proprostitution lobby and the sexual liberals have promoted prostitution as free sex and a viable profession for women, I now know that Butler was not only an important but also a problematic historical figure for me—because of the issues she challenged, and because of those she did not challenge. When I reread this chapter from Female Sexual Slavery and began to revise it, I was surprised to see the extent to which I had not explored the underlying bases of abolition, the foundations for abolitionist distinctions between “free” and “forced” prostitution. Challenging that distinction and showing it to be compromised is central to my work today, and so I was forced to reconsider the position I had taken on it in Female Sexual Slavery. Thus this work represents not only a revision of my previous thinking but also, to some extent, a reversal—or rather, not exactly a reversal but a new theory and policy orientation that I discuss in the last chapter.

The chapter on pimping has been revised, but not as dramatically as the others. Changes in pimping have taken place not so much in terms of practices as in terms of new approaches by the proprostitution lobby to have prostitution decriminalized and legitimized. However, with the normalization of prostitution in both the Third World and the West, I have significantly revised and expanded my study of state laws on pimping, all of which are still reducible to the idea of the “state as pimp.” This book has been written while I have been directing the Coalition Against Trafficking in Women and we have been developing a new international human-rights law against sexual exploitation. Working on this law with Janice Raymond, Dorchen Leidholdt, and Elizabeth DeFeis in the Coalition and human-rights advocates, especially Wassyla Tamzali at UNESCO and others at the United Nations, has enriched this work as much as this new research was brought to bear on the development of this international law. Elke Lassan’s translations of German reports and interviews have been invaluable to the international scope of this work.

I have slightly revised the chapter on Patricia Hearst, to explain why, personally and politically, her case was important in my study then and is still important to consider now. Furthermore, I have been able to expand upon the method of symbolic interaction that led to my original interpretive understanding of her case, an important approach to revealing the silences in women’s lives. However, there is another important reason for retaining this chapter. Many feminists, workers in rape-crisis and sexual-abuse programs, and victims of prostitution have frequently told me of the importance of this chapter and the chapter on the befriending and love strategies of pimps in explaining what Susan Hunter called “terror bonding.” Indeed, these are central chapters, describing elements of what Dee Graham in her important new work, Loving to Survive, refers to as a societal Stockholm Syndrome that likens women’s loving in patriarchy to the captivity of hostages.

It is my hope that with this book I have theoretically advanced the work against sexual exploitation and especially prostitution. I am not treating theory as an abstraction from reality. Feminist theory is theory only if it is rooted in women’s realities and from there reveals and explains women’s class condition.

The other new dimension of this work, which was not possible in my first book because it did not exist in the 1970s, appears in the last chapter, in which I have brought together a sampling of strategies—personal, local, regional, and international—for individual survival and international action—strategies that have been developing throughout the movement and around the world since the early 1980s—strategies that were not yet known when I was stuck in my isolation writing Female Sexual Slavery—strategies that reveal a world of feminist action, global commitments to confront patriarchy. For me these strategies, and the people behind them, represent not only effective actions but an interconnected movement, a struggle, a love of as much as a thirst for our liberation. To them this book is dedicated.