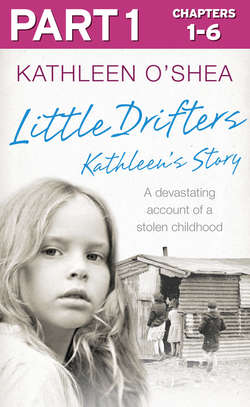

Читать книгу Little Drifters: Part 1 of 4 - Kathleen O’Shea - Страница 6

Prologue

ОглавлениеI never had any intention of returning to St Beatrice’s Orphanage. And yet here I was, standing in front of the house I had called home for five years. A home filled with misery, cruelty and abuse.

My eyes scanned the large black front door rising up from the path, the heavy wooden gates, the tree in the front garden, and I felt anger swell inside me. It was just a house. From the outside, you would never have guessed the secrets and sadness this place had hidden for so long. Now, nearly 20 years after my escape, it was no longer one of the houses run by the Sisters of Hope from St Beatrice’s Convent. It was no longer Watersbridge, a home for children made wards of the state from myriad different personal tragedies. It was just an ordinary house. You might pass by this house and not look at it twice. It was just like all the others in the road – two storeys, small front garden, large Victorian windows, nothing special. And yet that’s not what I saw.

I saw the children of my past in every part of the grounds, so real I felt I could reach out and touch them. So vivid, I could hear their voices. Here, on the roof, Jake squatted – keeping a watchful eye down the road for Sister Helen in case she came trundling down the road on her bicycle, ready to send up the signal to the rest of us that ‘Scald Fingers’ was returning. That’s when we’d all scurry through the gate to the garden at the back. There, sitting on the wall, was 10-year-old Megan, her bare legs swinging and kicking against the red bricks. Jake’s brother Miles clambered over the gate, one dangling leg testing the ground below before dropping into the front garden, where we loved to play, even though we weren’t allowed. Six-year-old Anne, the little girl I adored, sat in the crook of the tree’s branch, shouting and laughing at the children below, her pure white hair blowing around her pretty face like a halo. Shay, seven, rested on the ground, a look of fierce concentration on his face as his small, bony hands dug a hole in the earth with a twig. And scattered about, I saw others: James, Victoria, Jessica and Gina. I could picture every one of them – saw their fleeting smiles, their innocence, warmth and energy. Dead now. All of them dead.

‘You all right, Mum?’

My daughter Maya interrupted my thoughts and the visions started to recede from my sight. The voices drifted away and, as they left, I felt a familiar ache inside. I hadn’t spoken or moved in minutes. Maya stood at my side, concern in her voice and eyes.

‘Yes. Yes, I’m fine,’ I reassured her. I pulled my cardigan around me tighter, though it was a warm spring day.

‘Do you want to go in?’

I glanced again at the ghosts from my past as they played, carefree and happy. So much to look forward to back then. Now their voices would always be silent.

‘No.’ I shook my head. ‘I’d like to go now.’

I said goodbye to the children in the house and left them there – still playing, still blissfully unaware of their future. Too much pain, too much horror and torture went on in this house. I couldn’t bear seeing any more of those lost children.

The fact was, I had never intended to return to Watersbridge. It was purely by chance that my daughter and I, on a trip to visit my father, had decided to pass through this town again. But as I turned away, I realised that coming back was important.

You see, I made it.

Out of so many children that passed through these doors, I was among the very few that came out alive and in sound mind. I saw myself as no more than fortunate in that regard. I have struggled myself for years to fight down the demons from my past. I was lucky to come through the other side – many others did not.

So the fact that I was here at all was a symbol of defiance against this heartless place that tried to break us, my brothers and sisters, and those we came to look upon as our family. The fact that I came back with my own family was a sign that ultimately love won this battle for our souls, for our very survival.

But for those whom we lost along the way, I tell this story now.

For all the children who suffered in Catholic convent orphanages all over Ireland – the ones who died, the ones who lost their minds, the ones who drown the memories every day in a bottle of whiskey, I tell this for you. Because in the end we are all brothers and sisters – and if we don’t feel that, feel the bond of love between each other just as human beings, because we are human beings, then we are nothing. We are no better than the monsters who ran the orphanages.