Читать книгу Elegance - Kathleen Tessaro - Страница 10

ОглавлениеI’m on the train headed for Brondesbury Park to see my therapist. It’s my husband’s idea; he thinks there’s something wrong with me.

After we were married, I began to have recurring nightmares. I’d wake up screaming, convinced there was a man at the foot of the bed. The room would be exactly the way it was in waking life and then all of a sudden, he’d be there, leaning over me. I’d chase him away but he’d return every night without fail. After a while, my husband learnt to sleep through these nightly terrors, but when I started to cry during the day and couldn’t stop, he put his foot down. He explained to me that I had too many feelings and I’d better do something about it.

When I get to my therapist’s house, I ring the bell and am admitted into a waiting room, which is really part of a hallway with a chair and a coffee table. There are three magazines and have been ever since I started therapy two years ago: one House and Garden from spring 1997, and two copies of National Geographic. I can recite the contents of all of them. However, I pick up the copy of House and Garden and look again at the cottage transformed into a treasure trove of Swedish antiques using nothing but Ikea furniture and a few paint effects. I’m falling asleep when the door finally opens, and Mrs P asks me to step inside.

I take off my coat and sit on the edge of the daybed that is her version of a couch. The room is muted, sterile. Even the landscapes on the walls have an eerie calmness, like lobotomized Van Gogh’s – no wild, swirly, passionate mayhem here. I like to think that behind the glass door that separates her office from the rest of the house, there lies an explosion of primitive phallic art and dangerous modern furniture in a riot of vivid colours. The chances are slim but I live in hope.

Mrs P is middle aged and German. Like me, her fashion sense lacks a certain savoir-faire. Today she’s wearing a cream-coloured skirt with a pair of knee-highs, and when she sits down, I can see where the elastic pinches her leg, causing a red, swollen roll of flesh just under the knee. The German thing doesn’t help. Every time she asks me something, I feel like we’re enacting a badly-scripted interrogation scene from a World War Two film. This may or may not be the root of our communication problems.

I sit there and she stares at me from behind her square-rimmed glasses.

We’ve come to the impasse: part of our weekly routine.

I grin sheepishly.

‘I think I’ll sit up today,’ I say.

Mrs P blinks at me, unmoved. ‘And why would you like to do that?’

‘I want to see you.’

‘And why do you want to do that?’ she repeats. They always want to know why; there’s not really a lot of difference between a therapist and a four-year-old.

‘I don’t like to be alone. I feel alone when I’m lying down.’

‘But you’re not alone,’ she points out. ‘I’m here.’

‘Yes, but I can’t see you.’ I’m starting to feel really frustrated.

‘So,’ she adjusts her glasses further back on her nose, ‘you need to “see” someone in order not to feel alone?’

She’s speaking to me in italics, throwing my words back at me, the way therapists do. I won’t be bullied. ‘No, not always. But if I’m going to talk to you, I’d rather be looking at you.’ And with that, I push myself back on the daybed so that I’m leaning against the wall.

I start to pick at the bobbles in the white chenille throw that covers the bed. (I’m intimately acquainted with these bobbles.) Three or four minutes drag past in silence.

‘You do not trust me,’ she says at last.

‘No, I don’t trust you,’ I agree, not so much because I believe it to be true but because she says it is and after all, she is my therapist.

‘I think you need more sessions,’ she sighs.

Whenever I don’t do what she wants me to do, I need more sessions. There were whole months when I had to come every day. This is normally as far as we get; for two years we’ve been arguing about whether or not I should be allowed to sit up on the daybed. But today I have something to tell her.

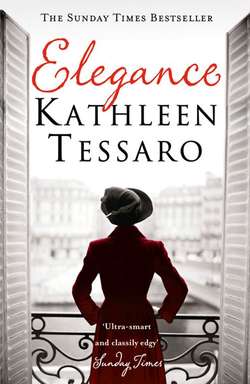

‘I bought a book yesterday. It’s called Elegance.’

‘Is it a novel?’

‘No, it’s a kind of self-help book, a guide that tells you how you can become elegant.’

She raises an eyebrow. ‘And what does “becoming elegant” mean to you?’

‘Being chic, sophisticated. You know, like Audrey Hepburn or Grace Kelly.’

‘And why is that important?’

I feel suddenly frivolous and girly – like a female member of the Communist Party caught reading an issue of Vogue. ‘Well, I don’t know that it’s important but it’s worth striving for, don’t you think?’ And then I spot her beige, orthopaedic sandals.

Maybe not.

I take another tack. ‘What I mean is, they were always pulled together, never unseemly or dishevelled in any way. Every time you saw them, they were perfectly groomed, faultlessly dressed.’

‘And is that what you would like, to be “pulled together, never unseemly or dishevelled in any way”?’

I think a moment. ‘Yes,’ I say at last. ‘I’d love to be clean and chic and not such a terrible mess all the time.’

‘I see.’ She nods her head. ‘You are not clean. That makes you dirty. Not chic. That makes you unfashionable. And a terrible mess. Not just a mess, but a terrible mess. So, you feel you are unattractive.’

She makes everything sound so much worse than it is.

Still, she has a point.

‘Well, no, I don’t feel very attractive,’ I admit, wincing inwardly as I say it. ‘The truth is, I feel the opposite of attractive. Like it doesn’t matter what I look like.’

She peers at me over the top of her glasses. ‘And why doesn’t it matter what you look like?’

A thick wave of unconsciousness swims up to meet me. ‘Because … I don’t know … because it just doesn’t matter.’ I try unsuccessfully to stifle a yawn.

‘But surely your husband notices,’ she insists.

I wonder what she means by ‘notices’. Is this some kind of euphemism? Does her husband ‘notice’ her in her knee-highs and skirt?

‘No, no he’s not that way,’ I explain, pushing the unwelcome vision of them ‘noticing’ each other from my mind. ‘He’s really not interested in that sort of thing.’ My eyelids are at half-mast now; it feels like they weigh a ton.

‘And what sort of thing is that?’

‘I don’t know … bodies, appearances, clothes.’

‘And how does that make you feel?’ she persists. ‘That he is not interested in your body, your appearance, or your clothes?’

I think for a moment. ‘Tired,’ I conclude. ‘It makes me feel tired. Anyway, why should he be interested in those things? He loves me for who I am, not the way I look.’ I’m sinking further and further into the daybed like a deflating balloon.

‘Yes, but love is not just a feeling,’ she continues, undeterred. ‘Or an idea. It’s completely natural that there is a physical side too. You are young. You are attractive. You are … falling asleep, am I right?’

I pull myself up with a jerk. ‘No, no I’m fine. Just a little drowsy. Late night last night.’ I don’t know why I bother to lie. Perhaps what she says is true: I don’t trust her.

‘Well, in any case, time is up for today.’

As soon as she says it, I start to revive.

I leave, head straight to the newsagent’s on the corner and buy two Kit Kats. I eat them in rapid succession, waiting for the train. I’ll never get this therapy gig. Can’t wait till I’m cured and have been given some sort of certificate I can show my husband.

A disembodied voice comes over the intercom to announce that, due to signalling problems, the next southbound train will be in twelve minutes. I sit down on a bench in the corner and take the copy of Elegance from my bag. A gust of wind rustles through it and the book falls open on a page from the preface.

From my earliest childhood, one of my principal preoccupations was to be well dressed, a somewhat precocious ambition that was encouraged by my mother, who was extremely fashion-conscious herself. Together we would go to the dressmaker and select combinations of fabrics and styles that ensured our outfits were entirely original and impossible to copy.

I think of my own mother and of how she hated shopping, dressing up or looking at herself in mirrors. Not only did she not aspire to elegance, but I believe she suspected it as a pursuit. It was at odds with the aesthetics of her strict Catholic upbringing, belonging as it did to the world of movie stars, debutantes and divorcees.

Pale and bespectacled, with short dark hair she cut herself, she preferred to spend most of her time in Birkenstocks and plain, loose trousers, maybe because in the male dominated world of science in which she excelled, fashion was of little practical use. However, in text book Freudian fashion, her unlived dreams and ambitions spilt out onto my sister and me. She longed for us to become professional ballet dancers, paragons of grace and discipline, and we trained for hours every day after school to that end. She indulged us in bizarre shopping trips, made more surreal by the fact that we rarely seemed to buy any actual children’s clothes. It was as if she was taking us shopping for her alter ego.

It’s a Saturday morning. My mother’s just picked me up from ballet class and we’re in Kaufmanns department store in Pittsburgh. I’m about twelve, but already I’m sporting a pair of high heels, ‘wedgies’ to be exact, with thick crepe soles and a denim wrap-around skirt, just like my idol, Farrah Fawcett in ‘Charlie’s Angels’. Like all the girls in ballet school, I want to look like a prima ballerina. We cake on tons of foundation, eyeliner and mascara and roll our eyes around like silent film stars on acid. We’re dying swans with our exaggerated posture, ridiculous turnouts, and scraped back hair-dos. It never occurs to us that make-up that’s meant to read on stage to the last row of the Metropolitan Opera House might not be suitable for street wear.

My mother and I are shopping in the eveningwear section. It’s 10:30 in the morning and we’re looking at sequins and taffeta. She’s going to a formal Christmas party with my father and we’re here to shop for her, but she can’t bear to look at herself or try anything on. I carry gown after gown into the changing room, where she’s slumped on the stool in her bra and girdle, cradling her head in her hands. ‘You put them on,’ she says and I do, preening and posing like a midget version of Maria Callas. My mother is a ghost, thin and shorn next to my drag act. ‘You’re so slim,’ she says, as I shimmy into a pink sequined sheath dress. ‘You look good in everything.’

We spend hours wading through piles of silk and satin and in the end she buys me a black sequined top and a cream coloured marabou jacket at vast expense, which I wear over my school uniform, despite the fact that it lands me in detention for a month.

My mother buys nothing.

And after we shop, we go to the chocolate counter and buy a pound box of Godiva chocolates, which we eat on our way back home in the car. My mother and I don’t do lunch. Lunch is, after all, fattening. So we sit in the front seat of the car, not looking at one another, cramming chocolate into our mouths instead.

By the time we get home, the excitement of shopping is gone. Vanished. Mom is suddenly furiously angry and I’m filled with fear and shame. She gets out, slams the car door and strides across the garage into the house, where I can hear her yelling at my brother. She yells for no reason – because a towel is badly folded or because the television is on. She yells because she hates herself; because she’s spent $300 on evening clothes for a twelve-year-old; because she’s so livid she can’t contain it any more. She throws something but misses.

I hear her storm upstairs and slam her bedroom door. Getting out of the car with my bags, I take the now empty chocolate box with me. It’s important that no one should see it. And I walk, or rather waddle the way dancers do, into the house. My brother’s there, crying, and there’s a pile of glass and plastic that used to be a clock around him on the floor. He looks at me with my Kaufmanns bags and the Godiva chocolate box and I know that he hates me. I stick my chin in the air and walk on. I am a bad person. I am a very bad person.

My mother doesn’t go to the Christmas party. She has an argument with my father and spends the evening locked in her room instead.

Closing the book, I get up and walk down to the end of the platform. In the corner, where the cement gives way to rubble and grass, I turn and throw up the two Kit Kat bars.

The light is softly dimming and I notice, as I wipe my fingers on a clean tissue, that the birds are singing, the way they do sometimes at dusk on early spring evenings. They sound impossibly hopeful.

And suddenly it occurs to me, that maybe my mother and I have something in common.

Maybe I come from a long line of women who felt like a terrible mess.