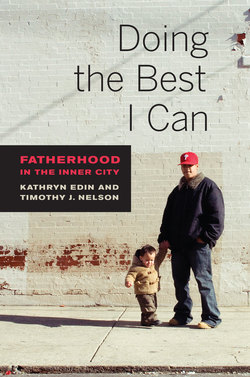

Читать книгу Doing the Best I Can - Kathryn Edin - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеIntroduction

“It is unmarried fathers who are missing in record numbers, who impregnate women and selfishly flee,” raged conservative former U.S. secretary of education William Bennett in his 2001 book, The Broken Hearth. “And it is these absent men, above all, who deserve our censure and disesteem. Abandoning alike those who they have taken as sexual partners, and whose lives they have created, they strike at the heart of the marital ideal, traduce generations yet to come, and disgrace their very manhood.”1 “No longer is a boy considered an embarrassment if he tries to run away from being the father of the unmarried child,” Bill Cosby declared in 2004 at the NAACP’s gala commemorating the fiftieth anniversary of Brown versus Board of Education, as he publicly indicted unwed fathers for merely “inserting the sperm cell” while blithely eschewing the responsibilities of fatherhood.2 Then, in 2007, two days before Father’s Day, presidential candidate Barack Obama admonished the congregants of Mount Moriah Baptist Church in Spartanburg, South Carolina, saying, “There are a lot of men out there who need to stop acting like boys, who need to realize that responsibility does not end at conception, who need to know that what makes you a man is not the ability to have a child but the courage to raise one.”3

Across the political spectrum, from Bennett to Obama, unwed fatherhood is denounced as one of the leading social problems of our day. These men are irresponsible, so the story goes. They hit and then run—run away, selfishly flee, act like boys rather than men. According to these portrayals, such men are interested in sex, not fatherhood. When their female conquests come up pregnant, they quickly flee the scene, leaving the expectant mother holding the diaper bag. Unwed fathers, you see, simply don’t care.4

About a decade before we began our exploration of the topic, the archetype of this “hit and run” unwed father made a dramatic media debut straight from the devastated streets of Newark, New Jersey, in a 1986 CBS Special Report, The Vanishing Family: Crisis in Black America. The program’s host, Great Society liberal Bill Moyers, promised viewers a vivid glimpse into the lives of the real people behind the ever-mounting statistics chronicling family breakdown.

But by far the most sensational aspect of the documentary—the segment referenced by almost every review, editorial, and commentary following the broadcast—was the footage of Timothy McSeed. As the camera zooms in on McSeed and Moyers on a Newark street corner, the voiceover reveals that McSeed has fathered six children by four different women. “I got strong sperm,” he says, grinning into the camera. When Moyers asks why he doesn’t use condoms, he scoffs, “Girls don’t like them things.” Yet Timothy says he doesn’t worry about any pregnancies that might result. “If a girl, you know, she’s having a baby, carryin’ a baby, that’s on her, you know? I’m not going to stop my pleasures.” Moyers then takes us back several weeks to the moment when Alice Johnson delivers Timothy’s sixth child. McSeed dances around the delivery room with glee, fists raised in the air like a victorious prizefighter. “I’m the king!” he shouts repeatedly. Later, Timothy blithely admits to Moyers that he doesn’t support any of his children. When pressed on this point, he shrugs, grins, and offers up the show’s most quoted line: “Well, the majority of the mothers are on welfare, [so] what I’m not doing the government does.”

The impact of The Vanishing Family was immediate and powerful, creating an almost instantaneous buzz in the editorial columns of leading newspapers.5 In the week after the broadcast, CBS News received hundreds of requests for tapes of the show, including three from U.S. senators. The California public schools created a logjam when they tried to order a copy for each of the 7,500 schools in their system. “It is the largest demand for a CBS News product we’ve ever had,” marveled senior vice president David Fuchs.6

The response to Timothy McSeed was particularly intense and visceral. An editorialist in the Washington Post could barely contain his outrage, writing, “One man Moyers talked to had six children by four different women. He recited his accomplishments with a grin you wanted to smash a fist into.”7 William Raspberry’s brother-in-law wrote the noted columnist that the day after viewing the program, he drove past a young black couple and found himself reacting with violent emotion. “I was looking at a problem, a threat, a catastrophe, a disease. Suspicion, disgust and contempt welled up within me.”8 But it was George Will who reached the heights of outraged rhetoric in his syndicated column, declaring that “the Timothies are more of a menace to black progress than the Bull Connors ever were.”9

The Vanishing Family went on to win every major award in journalism.10 Those commenting publicly on the broadcast were nearly unanimous in their ready acceptance of Timothy as the archetype of unmarried fatherhood. Congressional action soon followed: in May 1986 Senator Bill Bradley proposed the famous Bradley Amendment, the first of several of “deadbeat dad” laws aimed at tightening the screws on unwed fathers who fell behind on their child support, even if nonpayment was due to unemployment or incarceration. Only a lone correspondent from Canada’s Globe and Mail offered a rebuttal, fuming that Timothy “could have been cast by the Ku Klux Klan: you couldn’t find a black American more perfectly calculated to arouse loathing, contempt and fear.”11

Bill Moyers’s interest in the black family was not new. In 1965, two decades before The Vanishing Family was first broadcast, Daniel Patrick Moynihan, then assistant secretary of labor for President Lyndon Johnson, penned the now-infamous report titled The Negro Family: The Case for National Action. Moynihan claimed that due to the sharp increase in out-of-wedlock childbearing—a condition affecting only a small fraction of white children but one in five African Americans at the time—the black family, particularly in America’s inner cities, was nearing what he called “complete breakdown.”12 Moynihan was labeled a racist for his views, and Moyers, then an assistant press secretary to the president, helped manage the controversy.

Moynihan drew his data from the early 1960s, when America stood on the threshold of seismic social change. At the dawn of that decade, in February, four young African Americans refused to leave a segregated lunch counter in Greensboro, North Carolina, an action soon emulated across the South. In March the Eisenhower administration announced that 3,500 U.S. troops would be sent to a country called Vietnam. In May the public approved the first oral contraceptive for use. And in November an Irish Catholic was narrowly elected to the White House. Yet across the nation as a whole, nine in ten American children still went to bed each night in the same household as their biological father; black children were the outliers, as one in four lived without benefit of their father’s presence at home.13

Now, a half century after the Moynihan report was written, and two-and-a-half decades since Moyer’s award-winning broadcast, nearly three in ten American children live apart from their fathers. Divorce played a significant role in boosting these rates in the 1960s and 1970s, but by the mid-1980s, when Timothy McSeed shocked the nation, the change was being driven solely by increases in unwed parenthood. About four in every ten (41 percent) American children in 2008 were born outside of marriage, and, like Timothy’s six children, they are disproportionately minority and poor. A higher portion of white fathers give birth outside of marriage (29 percent) than black fathers did in Moynihan’s time, but rates among blacks and Hispanics have also grown dramatically—to 56 and 73 percent respectively.14 And the gap between unskilled Americans and the educated elite is especially wide. Here, the statistics are stunning: only about 6 percent of college-educated mothers’ births are nonmarital versus 60 percent of those of high school dropouts.15

In the wake of this dramatic increase in so-called fatherless families, public outrage has grown and policy makers have responded. In the 1960s and 1970s liberals worked to help supplement the incomes of single mothers, who were disproportionately poor, while conservatives balked, believing this would only reward those who put motherhood before marriage and would thus lead to more such families. Meanwhile, surly taxpayers increasingly demanded answers as to why their hard-earned dollars were going to support what many saw as an immoral lifestyle choice and not an unavoidable hardship. This taxpayer sentiment fueled Ronald Reagan’s efforts to sharply curtail welfare benefits in the 1980s and prompted Bill Clinton’s promise to “end welfare as we know it,” which he fulfilled in 1996.

Meanwhile, scholars have responded to the trend by devoting a huge amount of attention to studying single-parent families, detailing the struggles of the parents and documenting the deleterious effects on the children. These studies have offered the American public a wealth of knowledge about the lives of the mothers and their progeny, yet they have told us next to nothing about the fathers of these children.16 Part of the problem is that most surveys have provided very little systematic information from which to draw any kind of representative picture.17 Unwed fathers’ often-tenuous connections to households make them hard to find, and many refuse to admit to survey researchers that they have fathered children. Thus, vast numbers have been invisible to even the largest, most carefully conducted studies.18

The conventional wisdom spun by pundits and public intellectuals across the political spectrum blames the significant difficulties that so many children born to unwed parents face—poor performance in school, teen pregnancy and low school-completion rates, criminal behavior, and difficulty securing a steady job—on their fathers’ failure to care. The question that first prompted our multiyear exploration into the lives of inner-city, unmarried fathers is whether this is, in fact, the case.

CAMDEN AND THE PHILADELPHIA METROPOLITAN AREA

In the following chapters we go beyond the stereotyped portrayals of men like Timothy McSeed and delve deep into the lives of 110 white and black inner-city fathers. Each of the fathers whose stories we tell also hails from the urban core—in our case, Camden, New Jersey, and its sister city across the Delaware River, Philadelphia. Like McSeed’s Newark, these cities have some of the highest rates of nonmarital childbearing in the country. Roughly six in ten children in Philadelphia and an even greater percentage in Camden—nearly three out of four—are now born outside of marriage.

We argue that to truly comprehend unmarried fatherhood, it is not sufficient to focus on the men alone. Understanding their environments—the neighborhood contexts and the histories of the urban areas they are embedded in—is also essential. The streets of Camden and Philadelphia are such a critical part of the story, so we begin with a description of the neighborhoods we lived and worked in to gather the stories of the fathers whose lives we chronicle. At the outset of our study, we loaded a Ryder truck and moved into the Rosedale neighborhood of East Camden.19 We were to take up part-time residence in a tiny apartment carved from the first floor of a clapboard Victorian-era home on Thirty-Sixth Street near Westfield Avenue.

The two-room apartment became our headquarters that first sweltering summer as we tried to figure out how to approach the men we were interested in talking to and convince them to trust us. The fenced-in backyard behind the house, equipped with a deck, plastic lawn chairs, and a picnic table beneath a large oak tree, served as the location for many of our initial conversations during the gradually cooling evening hours, our dialogue accompanied by the buzz of the fluorescent back-porch light and the occasional siren or thumping bass from a passing car. This intensive fieldwork, living daily life among the families of the men we interviewed while raising our own children there, shaped our initial ideas and forged the set of questions we eventually posed to fathers across Camden and Philadelphia.

Our goal was to build relationships with unmarried fathers and engage them in a series of conversations, thereby gaining an in-depth knowledge of their experiences and worldviews. We began with two years of ethnographic fieldwork—hundreds of hours of observation and casual conversation—in Camden, followed by five years of repeated, in-depth interviewing across Camden and a number of Philadelphia neighborhoods. As we were writing this book, we visited each of these neighborhoods multiple times to collect supplementary information. We drew fathers from across Camden, from Greater Kensington (including Kensington, West Kensington, and Fishtown), Port Richmond, Fairhill, Harrogate, North Central, Strawberry Mansion, Nicetown, and Hunting Park—all north of Center City Philadelphia; from the Pennsport, Whitman, Grays Ferry, and Point Breeze sections of South Philadelphia; and from Elmwood Park, Mantua, Mill Creek, and Kingsessing in West Philadelphia (see table 1 and map 1 in the appendix).

East Camden, where our study began, has the mix of housing typical of the Philadelphia metropolitan area. Row homes are the most common dwelling type, usually plain brick affairs. Twins come next—each side often in a different state of repair, with occupants seemingly eager to distinguish their side from its mirror image with different trim colors, distinctive siding, and layers of gingerbread. Here and there, only one-half of the twin now stands, creating an eerie asymmetrical look. Then there are the singles, most built in a simple Victorian-farmhouse style, but some in stone with pillars bracing roofs that reach over deep porches.

When we arrive in early summer, everything is in bloom— prawling hydrangeas, climbing roses, lush crepe myrtle. In the deep backyards there are several aging aboveground pools, though few seem to be in use—one is totally covered with dead branches. To compensate, parents place plastic kiddie pools in their yards. But perhaps the most noticeable thing about the relatively quiet side streets for the newcomer is the trash—it lines curbs and sidewalks everywhere. We’ll soon observe how the city’s sanitary engineers seem to show their contempt for the neighborhood by ensuring that only a portion of the garbage they collect actually finds its way into the back of their trucks.

Homeowners ward off the neighborhood squalor by encasing every square inch of their property with chain-link fencing, sometimes adding the green plastic fill that creates a greater sense of privacy. Secure in these compounds, the more affluent residents—civil servants and immigrants running small businesses—tune out the neighborhood that surrounds them and focus instead on their little pieces of heaven. Cars usually park inside the fenced perimeters, not on the street. Few homes have garages, but many have freestanding metal carports with arched roofs, often listing to one side or another. Inside these dubious structures, we spot church vans for a dozen congregations, the trucks of food vendors, cement trucks, junk cars, and the like. One morning we see evidence of an informal restaurant alongside such a structure, with dozens of small tables in the backyard. In the driveway two black men wrestle a small cement mixer into the back of a truck ready for a day’s labor. Later, they’ll presumably drink beer and cook ribs for their patrons on huge half barrels serving as grills.

By the time we arrive in Rosedale, this once-desirable residential section of the industrial town has mostly lost the struggle against poverty and crime. The oldest, largest, and most notorious of the city’s nine housing projects, Westfield Acres, located on Westfield Avenue at Thirty-Second Street, looms over the neighborhood’s main thoroughfare, though the housing authority is about to demolish its high-rise towers. Over the years the area has earned a certain reputation; the Philadelphia Inquirer won’t deliver to the local convenience stores because the drivers are afraid to enter the neighborhood, we can’t get a pizza delivered, and even the Maytag repairman won’t come, as we learn when our washing machine breaks down.

Like many inner-city neighborhoods, Rosedale is in a war between the homeowners struggling for a slice of respectability and the tawdry row homes and public-housing tracts that provide shelter for some of the most disadvantaged families in the metropolitan area. The homeowners arm themselves against blight in any number of ways: disguising rotting clapboards with aluminum siding, replacing 1920s single-pane windows with new vinyl models, converting the front yard into a concrete pedestal for the family car, and so on. Porches typically come last on the list of pressing home improvements. Some are encased in wrought-iron cages—often quite decorative—for added security, but others are left undefended and sagging. On main avenues homeowners’ battle against undesirable, and possibly dangerous, passersby intensifies—those first floor windows not fortified by wrought iron are sometimes simply boarded up, with drywall applied right over the opening on the inside.

East Camden, the section of the city where Rosedale lies, was almost exclusively white until the mid-1960s. By the time its first black residents began to appear in the early 1970s, at the tail end of the great migration of African Americans northward, the city and neighborhood were still places of promise and hope. Separated from the rest of the city by the Cooper River, East Camden was laid out in the late 1800s by developers to attract immigrants and rural dwellers with modest means. Yet some of the twins and singles were almost opulent, made not of red brick but of stone—the native mica-infused granite that made these structures literally sparkle in the sun. Evidence of that time exists even now, for if one steps off of Westfield Avenue onto Rosedale or Merrill or any of the numbered streets, some of these distinctive structures still stand. In this residential area bordering an agricultural zone, one was more likely to hear a rooster’s crow than a factory’s whistle a hundred years ago. Even now, the neighborhood families sometimes raise chickens, so it is not unusual to hear the crow of a rooster.

If one walked the length of Westfield Avenue in 1950, its golden age, there were literally hundreds of shops.20 On the 2600 block alone, where the avenue began, one could while away a Saturday afternoon browsing the Father & Son Shoe Store, Walen’s Men’s Wear, the Clover Children’s Clothing Shop, Sun Shoe Repair, the Pastorfield Wallpaper Company, Jane Dale’s Women’s Furnishings, ABC Cleaners, the Sugar Bowl Confectioners, Devoe and Reynolds Artist’s Materials, Westview Hardware, the New York Fashion Shop, Lester’s 5&10 Cent Store and more. Most exciting for the neighborhood youth of the day was the lavish Argo Movie Theatre.

Fueling this heady prosperity was the mighty industry in North and South Camden. Originally a bucolic backwater in the shadow of its more powerful neighbor across the river, Camden became an industrial powerhouse in its own right by the late nineteenth century. By the end of the 1960s city leaders still believed Camden was on the upsurge. RCA Victor was the largest producer of phonographs and phonograph records for the first two-thirds of the twentieth century. New York Shipyards was the nation’s largest shipbuilder during World War II, and the Campbell Corporation was the world leader in the production of canned vegetables and condensed soup. These three industrial giants, all founded in Camden roughly a century earlier, provided enough jobs for 75 percent of the manufacturing workforce. And while none of these firms had ever hired many African Americans, for more than a century black men had found their employment in their shadow, with jobs as teamsters, stevedores, and coopers that were contingent on the city’s industrial economy.21

But just below the surface, signs of trouble were everywhere. A prime culprit was the residential trend toward suburbanization that had so many American cities in its grip. Camden’s population had peaked at 125,000 in 1950 but was down nearly 20 percent by 1970. Young couples eager to establish themselves—spurred by Federal Housing Administration policies that made it hard, if not impossible, to secure a mortgage in the city but easy to finance a home in towns with pastoral-sounding names like Mount Laurel, Cherry Hill, or Audubon—offered a ready ear to suburban real estate boosters who proclaimed, “Why live in Camden or Philadelphia when you could live here?”22

Second, though city politicians were in denial, 1960s Camden was already beginning to hemorrhage manufacturing jobs, down 45 percent in that decade alone. Some of the city’s shocking job loss was due to the abrupt closure of the New York Shipyards because of declining demand, but other, smaller manufacturers who felt pressure to modernize or expand were leaving as well.23 Meanwhile, suburban industrial employment grew by 95 percent, luring even more of the city’s younger industrial workers away from the Camden neighborhoods of their youth.

Third, businesses had already begun a slow exodus east to Cherry Hill, Morristown, Woodbury, and Voorhees, following their customer base. In the 1950s the city boasted large, prosperous department stores—nearly every major chain in the region was represented—elegant theaters, the grand 1925 Walt Whitman hotel, and hundreds of small family-owned shops along the city’s major commercial spines: Broadway, Kaighns, Haddon, and East Camden’s Federal and Westfield. Then, in 1961 the first shopping mall on the East Coast opened its doors, the Cherry Hill Mall, to a frenzy of acclaim, just a short five-mile drive from Camden’s eastern border. “Shop in Eden all Year Long,” advertisements read, referring to the mall’s air conditioning. Over the next ten years, vacancies along Camden’s commercial arteries grew rapidly.24

The year 1971, though, was when Camden exploded in racial violence, and this dealt its deathblow. The Camden Courier-Post had reported increasing racial tension in Camden during the prior decade, as Philadelphia (1964), Watts (1965), Newark (1967), Detroit (1967), Chicago (1968), Washington, DC (1968) and Baltimore (1969) had erupted, yet other than a series of civil disturbances in 1969, no major riot had occurred in Camden. Then, in the course of a routine traffic stop, a local Puerto Rican man was nearly beaten to death by two white police officers.25

By then Camden had a sizable Puerto Rican population, first initiated by Campbell’s Soup’s decision to cure their acute labor shortages during World War II by recruiting workers from Puerto Rico. Mayor Joseph M. Nardi, a Camden-born Italian American relatively new to his post, refused to suspend the officers involved. Throughout the day the crowd of Puerto Rican protesters gathered in front of city hall grew to as much as 1,200. Finally, around 8 p.m. Nardi agreed to meet with the group’s leaders. While they were laying out their demands for more Puerto Rican men on the police force and better schools, housing, and employment, a bar fight overflowed onto the street and sparked a wave of looting, burning, and rioting that lasted three days. The city’s entire 328-man police force responded, reinforced by 75 state police troopers and 70 officers from surrounding areas. By the morning of the fourth day, the Camden Courier-Post reported, “The city’s major streets were bombed-out ruins, littered with broken glass, burned trash, objects hurled by demonstrators and spent tear gas containers. Water from firefighting and from fire hydrants turned on by residents made a soggy mess of the debris.” Nearly every plate-glass window along Broadway from Federal Street to Kaighns Avenue was smashed.26 In the years immediately following, almost all major retailers left the city and so did almost every large employer.27

Four decades later fewer than twenty-five thousand households remained in the city. Half of its residents were African American and more than four in ten were Hispanic—most of them Puerto Rican—with only a smattering of elderly whites and newcomer Asians. Median household income remained abysmally low—under twenty-nine thousand dollars—and more than a third of Camden’s families lived below the official poverty line: 44 percent of families with children were poor. Unemployment between 2008 and 2010 averaged 22 percent. Roughly 15 percent of the city’s households claimed government disability payments (SSI), and about 12 percent received cash payments from the welfare system, while nearly three in ten collected Food Stamps—all very high rates as compared with the nation as a whole. Four in ten adults lacked a high school diploma or GED, and the high school dropout rate stood at 70 percent.28

From the days of the Moynihan controversy onward, academic researchers and journalists who have focused on the lives of so-called fatherless families have looked almost exclusively at African Americans, lending the impression that “fatherlessness” is a black problem. By the mid-1990s, however, black rates of unwed childbearing had leveled off, while among whites (and Hispanics) the growth was substantial. By the end of that decade 40 percent of all nonmarital births in the United States were to non-Hispanic whites, while only a third were to blacks.29 By the time we began our study, the so-called fatherless family, which Moynihan had labeled a black issue, had spread beyond America’s disadvantaged minorities.

Thus, though we started in Camden, we expanded our focus to lower-income neighborhoods in Philadelphia, a city with minority neighborhoods with similar social ills as Camden’s but also with predominantly white neighborhoods that, while not nearly as poor as some of its black sections, still had pockets of poverty.30 Philadelphia was also an industrial giant, and it too peaked in the 1950s. As noted earlier, it also had an influential race riot in 1964 that coincided with dramatic changes in the economic and racial complexion of the city.

Today Philadelphia is a largely black and white city, with only a small representation of Hispanics and Asians. The median household income stands at just under thirty-six thousand dollars, and poverty rates are much lower than Camden’s—20 percent (29 percent of families with children). A much smaller proportion claim government assistance in Philadelphia.31 Unemployment, at 13 percent, is still above the national average. Nearly eight out of ten adults (79 percent) have at least a GED, but only 56 percent of the city’s public high school students graduate within four years.32

Taken together, the metro area as a whole bears similarity to many rustbelt cities in the Northeast, Midwest, and Mid-Atlantic regions. In 2011 its unemployment rate stood at just under 9 percent, similar to rates in the Baltimore, Cleveland, New York, Milwaukee, Saint Louis, Cincinnati, and Chicago metropolitan areas. Out of the forty-nine largest metro areas, it ranks twenty-second by this measure.33 Still, Camden and Philadelphia are among the nation’s poorest cities—in 2007 Philadelphia was the ninth poorest of all large cities, while Camden was narrowly edged out by Bloomington, Indiana, as the poorest city in the nation, a designation Camden has earned in most years.34 At this writing it has just earned the title again, edging out last year’s winner, Reading, Pennsylvania. It is also America’s second most dangerous city, but a recent spate of murders has put it very close on the heels of the first-place winner, Flint, Michigan.35 Given the stark economic conditions of Philadelphia and Camden and the income restrictions we imposed on our sample—which we limited to men earning less than sixteen thousand dollars in the prior year in the formal economy (roughly the poverty line for a family of four in 2000)—our results must be interpreted with some caution; not all unwed fathers live in places with so many economic challenges, nor are all unwed fathers as disadvantaged as the men in our story. But because a disproportionate number of unmarried fathers are disadvantaged across a variety of domains, many men who have a child without benefit of a marital tie do so under similar conditions.

Nationwide, poor whites rarely live in neighborhoods of concentrated poverty, and Hispanics are also less likely than African Americans to do so. This substantial difference in neighborhood conditions sometimes leads to misleading comparisons, for while disadvantaged minorities usually come of age in communities with daunting challenges and precious few resources, poor whites are much more likely to enjoy the good schools, safe streets, plentiful jobs, and enriching social activities that are so beneficial to young people as they navigate the transition to adulthood. Philadelphia offered us an unusual advantage: the chance to study disadvantaged whites whose neighborhood contexts were somewhat more similar to those of economically challenged blacks. In selecting our neighborhoods, we took full advantage of this feature of the city.

THE FATHERS

Over the seven years we spent on street corners and front stoops, in front rooms and kitchens, at fast food restaurants, rec centers, and bars in each of these neighborhoods, we persuaded 110 low-income unwed fathers to share their stories with us, sometimes over the course of several months, or even years. We recruited roughly equal numbers of African Americans and whites, the two groups who constitute the large majority of the population in the Philadelphia metropolitan area.36 Fathers ranged in age from seventeen to sixty-four, yet we made sure that roughly half of the fathers were over thirty when we spoke with them so we could tell the story of inner-city unwed fatherhood across the life course. Their experiences were varied, but all were fathers with at least one child under the age of nineteen they did not have legal custody of, and all hailed from city tracts that were working class or poor.37

Because the men we were interested in talking with were often not stably attached to households, and some were involved in illicit activities they were eager to hide from outsiders, we did not attempt a random sample; instead, we tried for as much heterogeneity as we could.38 Within each poor and working-class neighborhood we had identified using census data, we began by trying to solicit referrals from grassroots community organizations and social service agencies. But we soon learned that few of the fathers we sought were involved in these groups, and those who were—usually drug addicts in rehab or homeless men sleeping in shelters—were far from representative. We then visited local business strips, train and trolley stops, day labor agencies, and other employers in these neighborhoods in the late afternoons, when work shifts ended and many residents were out and about. We also simply walked the streets, striking up casual conversations with men we encountered and posting fliers on telephone poles and in corner stores, check-cashing outlets, liquor stores, and bars. We also invited early participants to refer us to other fathers whom we might have missed on our own.

With these unconventional recruitment strategies, it was surprisingly easy to convince fathers to talk with us. Getting them to speak candidly about their views and experiences required more work. No researchers enter fully into the lives of their subjects, and we do not claim to have done so. In the end what won the confidence of most men was our willingness to become neighbors and our eagerness to gain some firsthand experience with the contexts in which they lived. Our own backgrounds still marked us as outsiders but also allowed us to authentically claim the role of novices seeking the fathers’ expertise in understanding the rhythm and risks of daily life.39

Our conversations with each father, usually stretching across several meetings, were wide-ranging and in-depth. We asked fathers to begin by describing their own childhoods and families of origin, and what it was like for them growing up. We tracked their paths through adolescence and early adulthood; their experiences with peers, school, and work; and the beginning and end of each romantic relationship. They described the circumstances surrounding the births of each of their children and the often shifting patterns of involvement in their children’s lives. We asked how they had come to make the choices they had, what they wished had gone differently, and what they planned for the future.

The question that originally prompted our study—is it true that these fathers simply don’t care about the children they conceive?—led to a deeper and more complex focus of inquiry: what does fatherhood mean in the lives of low-income, inner-city men? This query spurred us to chronicle the processes of courtship, conception, and the breakup of the romantic bond. We then looked at how fathers viewed both the traditional aspects of the fatherhood role—being a breadwinner and role model—and its softer side. Finally, we elicited the barriers men faced as they tried to father their children in the way that they desired, and how they responded to these challenges. Our goal was to offer honest, on-the-ground answers to the questions so many Americans ask about these men and their lives.

In this book we do not seek to portray the whole way of life in these communities. The voices of the women these men share children with only rarely enter in, for example, and this is intentional; their stories have already been told.40 Nor do we discuss men who have earned college degrees, have managed to land and keep higher-paid manufacturing or white-collar jobs, or are raising their children within marriage, though men with these characteristics also reside in these communities. This is not a book about race; though we note racial differences when they occur, they are more in degree than in kind. In this narrative, where black and white men live in more similar contexts than in most places, racial differences are far outweighed by shared social class. This is not a work of history; we do not, and cannot, present the narratives of low-income fathers at earlier points in time such as the 1950s and 1960s—what some conceive of as the golden age of family life.41 We do not offer an analysis of the individual characteristics or contexts associated with fathering a child outside of a marital bond—that question would have required a very different study design than ours. Nor do we engage with the rich literature on father involvement, though readers can find references to this literature in the notes to the book. Finally, this is not a book about the effects of fathers’ behaviors on their children’s well-being, though we do discuss the implications for children in the final chapter.

This is the story of disadvantaged fathers living in a struggling rustbelt metropolis at the turn of the twenty-first century. By examining each father’s story as it unfolds, we offer a strong corrective to the conventional wisdom regarding fatherhood in America’s inner cities. There is seldom anything fixed about the lives of the men in this book—not their romantic attachments, their jobs, or their ties to their kids. Only by revealing how they grapple with shifting contexts over time can we fully understand how so many will ultimately fail to play a significant and ongoing role in their children’s lives.

The men in these pages seldom deliberately choose whom to have a child with; instead “one thing just leads to another” and a baby is born. Yet men often greet the news that they’re going to become a dad with enthusiasm and a burst of optimism that despite past failures they can turn things around. Conception usually happens so quickly that the “real relationship” doesn’t begin until the fuse of impending parenthood has been lit. For these couples, children aren’t the expression of commitment; they are the source. In these early days, men often work hard to “get it together” for the sake of the baby—they try to stop doing the “stupid shit” (a term for the risky behavior that has led to past troubles) and to become the man their baby’s mother thinks family life requires. But in the end, the bond—which is all about the baby—is usually too weak to bring about the transformation required.

Not surprisingly, these relationships usually end, but instead of walking away from their kids, these men are often determined to play a vital role in their children’s lives. This turns out to be far harder than they had envisioned. Nonetheless, they try to reclaim fatherhood by radically redefining the father role. These disadvantaged dads recoil at the notion that they are just a paycheck—they insist that their role is to “be there”: to show love and spend quality time. In their view, what’s most important is to become their children’s best friends. But this definition of fatherhood leaves all the hard jobs—the breadwinning, the discipline, and the moral guidance—to the moms.

As children age, an inner-city father’s scorecard can easily show far more failures than successes, particularly because of the “stupid shit” he often finds so hard to shake. In this situation, it can require incredible tenacity and inner strength to stay involved. But few of these men give fatherhood only one try. Each new relationship offers another opportunity for “one thing” to “just lead to another” yet again. And a new baby with a new partner offers the tantalizing possibility of a fresh start. In the end, most men believe they’ve succeeded at fatherhood because they are managing to parent at least one of their children well at any given time. Yet this pattern of selective fathering leaves many children without much in the way of a dad.

By examining the unfolding stories of these men’s lives beginning at courtship, and moving through conception, birth, and beyond, we come to see that the “hit and run” image of unwed fatherhood Moyers created by showcasing Timothy McSeed is a caricature and not an accurate rendering—a caricature that obscures more than it reveals. Some readers will argue that our portrayal is no more sympathetic, or less disturbing, than Moyers’s. Others will find seeds of hope in these stories, albeit mixed with a strong dose of disheartening reality. But getting the story right is critical if we hope to craft policies to improve the lives of inner-city men and women and, of course, their children.