Читать книгу The Trouble with Murder - Kathy Krevat - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеChapter 1

A chicken rang the doorbell.

I stood in the open doorway, a little dumbfounded, and stared down at the beige bird with a mop of floppy feathers on its head that looked like a hat. The kind of hat women wore as a half joke to opening day at the horse races. How could it even see through that thing? And did it really just ring the doorbell?

Braving the mid-morning heat of Sunnyside, California, inland from downtown San Diego by twenty miles and what felt like twenty degrees hotter, I stuck my head out and looked up and down my dad’s street. No teens were hanging around, giggling over their prank.

The chicken ruffled its whole body as if to say, “Yes, it was me.” The you idiot was implied by the way it poked his beak toward me and then scratched its feet on the wooden porch floor.

“Right.” I spoke out loud. To a chicken. I had to get out of the house more.

I’d been up since four in the morning, grinding various chicken parts and cooking them for my organic cat food business, and I was already tired. Maybe this was a poultry hallucination brought on by exhaustion. Or induced by guilt.

Maybe this was the king of the chicken underworld, seeking retribution for what was going on in my kitchen.

I shook my head. I had to stop reading so many of those horror novels my bloodthirsty twelve-year-old son, Elliott, couldn’t get enough of.

My dad shuffled over to stand beside me, tugging his bathrobe tighter around his waist. “Hey, Charlie,” he said.

I raised my eyebrows. He was talking to a bird too. “A boy bird?” I asked. Was that really the most important thing about the chicken on our doorstep?

The chicken ignored both of us, now finding the railing fascinating enough to peck.

“Of course he’s a boy bird,” he said, his Boston accent coming through. “He’s one of Joss’s Buff Laces.”

“What?”

“His chickens. This is a Buff Laced Polish chicken,” he said. “Look at that comb.”

“Comb?” I asked.

“That foofy thing on the top of his head,” he told me.

The comb in question was quite remarkable, but what did I know about chickens?

“How did it, he, make it to the doorbell?” I thought chickens didn’t fly. Wasn’t that the whole point of them? Food that can’t fly away?

“Charlie was owned by some shrink at a college or something,” he said, his normal morning mad-scientist hair almost matching the bird’s.

As if to demonstrate, Charlie flapped his wings, getting enough lift to hop onto the planter with some drooping lavender in it. He stretched out his neck to poke his beak at the doorbell. It took a few tries but then he got it, tilting his head as though he was listening to the “Yankee Doodle” tune that made me grind my teeth every time I heard it, and then hopped down, looking up at me expectantly.

Maybe this one was some kind of X-Games chicken.

“Does he want a treat?” I asked my dad.

Then my cat, Trouble, gave a low warning snarl that Charlie seemed to recognize because he turned around and fluttered down the steps in half-flight-half-run. I grabbed Trouble just as she was about to chase after the poor bird, and handed her to my dad. “Take her,” I said. “I’ll make sure Charlie gets home.”

Trouble had been an apartment cat and hadn’t been very curious about the outside world until we moved out of the city to my dad’s house. Now we had to make sure she didn’t escape every time we opened a door.

My dad held Trouble with his hands outstretched, looking unsure. Which was probably because she was still in full battle mode and swatted at me as soon as she could twist around in his arms, screeching, “Let me at ’em.”

Not really, but I knew what she meant.

“She’ll calm down in a minute,” I told my dad as I dashed after the chicken.

Charlie was sticking to the sidewalk, but headed in the opposite direction from his home. After the doorbell stunt, I imagined he knew his way around town. But it wasn’t up to me to keep him safe on an adventure. I just wanted to get him back to his pen.

Within seconds, I was dripping with sweat and regretting not grabbing my sunglasses. The glare of the mid-morning sun irritated my eyes that already felt scratchy from lack of sleep.

I ran in front of Charlie and attempted to sheep-dog him back the other way. He scooted around me.

“Damnit,” I said, and hustled to get past him. He must have decided it was a race because he started running, determined to reach his goal, whatever that was.

I got in front of him, my huffing and puffing making me realize I should get back to the gym, and yelled, “Shoo!” while waving my arms like a…like a chicken.

He came to a stop in the most theatrical, wings flapping, squawking protest the world had ever seen, and reversed course.

“Drama queen,” I said, hoping he didn’t keep up the complaining all the way back. I hadn’t yet met our neighbor, Joss Hayden, but something made me think that a certified organic farmer might not like me upsetting his chicken. Of course, I’d heard all about him from my dad, who said he was the best neighbor ever, occasional chicken coop odor notwithstanding.

Joss had bought the farm a year before, kept to himself, didn’t have any parties, and didn’t borrow any tools. I’d only seen a glimpse of him from a distance and imagined him to be some eccentric hippy, or even worse, a hipster dude getting back to nature. He grew organic vegetables in addition to his free-range chicken business.

Elliott had become a fan of Joss too, although that was probably more about visiting the baby chicks than the farmer himself.

It didn’t take long for the traumatized chicken to scurry home, probably to blab to all his chicken friends about the torture he’d endured on his jaunt. The metal gates to the various pens were all locked. How did he get out? I was about to put him back in the closest one but realized he might belong somewhere else, so I went to the front door. Charlie followed along, hopping up the two steps to join me. Then the smart aleck ran across my foot, making me jump a bit, to ring the doorbell before I could. Joss the farmer was lucky enough to have a normal ding-dong doorbell. We both stood and waited.

A man wearing a black T-shirt answered the door with an annoyed expression. Even with the frown, he was attractive, in a non-hippy, non-hipster way. More like a muscular-guy-who-puts-out-a-fire-and-then-drives-off-on-a-motorcycle way. He looked from Charlie to me and his expression became confused. “You’re not Charlie.”

Ah, he must be a constant victim of the button-pushing. “Nope. Charlie rang my doorbell, and I brought him back.” I held out my hand and then remembered that they’d been wrist deep in chicken livers. Even though I’d worn gloves to my elbows, it felt inappropriate. I pulled my hand back. “Colbie Summers. I’m, uh, helping out my dad a bit.”

He’d reached out to shake my hand and it hung out there, shake-less.

“I’ve been handling…meat,” I explained.

He smiled, as if figuring out I’d been holding chicken parts. “For your cat food business,” he said. The wrinkles around his eyes deepened, and I noticed how blue they were.

Whoa. That was a nice smile. “Um, yes,” I said, practically stuttering. “This batch is just for taste-testing. Not by me. By Trouble. You know. My cat.” Although I had been known to try a few of the recipes. “The food I sell is actually made in a commercial kitchen.” Stop talking, I told myself.

Charlie seemed to lose interest and jumped back down the steps.

“Your dad told me about Trouble,” he said, keeping an eye on the chicken. “Sorry about the whole doorbell thing. Charlie was used for some kind of psychology experiments by his previous owner and will poke at anything button-like.”

“It’s okay,” I said.

He shook his head as he came out and closed the door. “I don’t know how he gets out all the time. He’s the best escape artist I ever had.” He walked to the edge of the porch. “It must be the trough. It’s too close to the fence but I’d need a crane to move it.”

From that viewpoint the farm was picture perfect—its large red barn painted with white trim, a green tractor parked beside old-fashioned gas tanks, and the chickens scratching in the pens. “Sorry,” I said. “Don’t have one of those with me.” I turned to go. “Nice meeting you. Good luck with Charlie.” I wasn’t going to tell him that I couldn’t leave my chicken livers marinating in green curry very long or the flavor would be too intense for my feline customers.

“Nice to meet you,” he said. “You want to see the chicks before you rush back?”

“Um…” Was that how a chicken farmer made his move? I did a quick inventory of what I looked like. Cut off shorts to deal with the heat, a Padres Tshirt stained with meat juice, flip-flops, and a rolled-up bandana around my light brown hair with the copper stripe I needed to revive. And, oh yeah, red-rimmed eyes and no makeup. I was definitely safe from any moves by the farmer. And who could resist chicks? “Sure.”

He jogged down the porch steps and walked back to the pen, scooping up Charlie as he opened the gate, and setting him down inside a pen by himself. Some chickens in the next section moved closer as if to check out the action. “In here,” Joss said.

I walked carefully through the pen, watching where I put my feet. The door to the chicken coop was open and a few birds sat in nests. Then he opened a door inside and we were in some kind of incubator room. An orchestra of chick peeps reached a crescendo and an overwhelming chicken poop scent whooshed by.

“Whoa,” I said, plugging my nose and then looking over apologetically.

“Sorry,” he said cheerfully. “It takes a little getting used to.”

When Joss moved closer, the chirping became even louder.

“So, the chicks love you,” I said, not being able to resist the pun.

He looked startled for a second until he realized I was joking. “These are a bit too young for me.”

I moved closer to the raised wooden beds with high sides holding the chicks. Heat lamps shone on them, even when it was so hot outside, and the brown and black fuzz balls moved closer to us. “They’re adorable,” I said. “They don’t look like Charlie.”

“No,” Joss said. “They’re Ameraucanas. They lay blue eggs.” He picked one up gently. “Here.” He put the baby chick in my cupped hands.

I couldn’t help but say, “Aw.”

And then it pooped. Right in my hand.

“Oops,” he said. “Occupational hazard.”

And then it pooped again.

“Let me—” he started, and I gladly tipped the chick into his hands. For some reason, I kept my hands together to prevent the mess from escaping, even though there was plenty on the floor.

He gently placed the creature back in its home, and pulled a wet wipe from a handy container hanging high above chicken level by the back door. “Here,” he repeated, his eyes laughing at me.

“I got it.” I grabbed the wipe, cleaning my hands as quickly as I could. “I’m a mom,” I said a little defensively. “A little poop doesn’t bother me.” Of course, chicken poop was a different story. “I better get back.” To wash my hands with bleach.

He opened the back door and I walked outside, the sun accosting my eyes again. Then I hit something slimy, sliding a whole two feet and wind-milling my arms before coming to a halt.

I looked down.

A hose had leaked, creating a slimy puddle of mud and chicken poop, which was now slopped all over my flip flops that were pointing in different directions, my feet solidly in the mess.

This time, Joss looked chagrined. “Sorry, sorry. I meant to replace that.…” He looked at my feet as if not knowing what to do, and then bit his lip, trying not to smile.

“I’ll…” Burn these didn’t seem nice to say out loud. “Just go…”

“Yeah,” he said, valiantly holding back laughter.

Men never outgrow poop humor.

I walked back to my dad’s house, futilely attempting to scrape the mess off my flip flops onto the tiny patches of grass that lined the sidewalks. That was sticky stuff.

My dad’s street looked like it could be in a seventies sitcom, with neat row houses, all the same white stucco walls and red clay tile roofs. Small driveways led to separate two car garages in the back, usually used for storage or workshops. Every yard hosted a few palm trees and a dried-out lawn that wasn’t doing a good job surviving the summer drought regulations. The houses on my dad’s side backed up to a huge family farm. The farmer had refused to sell to developers, so my dad had the best of both worlds. The convenience of all things suburbia and a wonderful view of open farmland. Of course, that open farmland smelled strongly of fertilizer at times, but it was worth it.

I tossed my disgusting flip flops and the poop-covered wipe in the garbage and used the garden hose to clean my feet before heading inside.

“Your phone rang,” my dad called out from the living room over the sound of Storage Wars, his favorite show.

I grabbed my cell and headed back to the stove, tripping over the now-loving cat who wound around my ankles and purred, clearly saying, “I wuv you so much. Isn’t it time to taste test?”

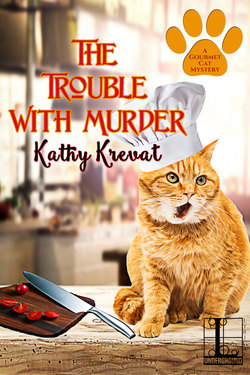

My Meowio Batali Gourmet Cat Food was marketed as organic food for the discerning cat, and many of my customers welcomed the most exotic of spices. But if Trouble didn’t like it, I dropped it. I’d learned early on that she never steered me wrong. If she liked it, it sold. If she didn’t like it, other cats didn’t either.

My whole business was inspired by Trouble. I’d found her, not even six weeks old, abandoned in an apartment when a tenant skipped out on the rent. Elliott and I immediately fell in love with her tiny orange face and white paws, and adopted her. Because of the splash of white on her chest, Elliott had originally wanted to call her Skimbleshanks, after a cat character in the musical Cats.

She’d had a lot of digestive problems, and the only food she could handle was what I made. That, combined with her natural kitten mischievousness, earned her the name Trouble.

Soon, friends started asking to buy little jars of the same food for their cats, which is how I learned that there was a demand for organic, human-grade cat food. I increased my production, cooking at odd hours when I could sneak it in around my job managing the apartment building where we lived.

When I’d tried to expand to farmers’ markets, I learned there were a lot of regulations I’d have to follow to make it a real business, including cooking all the food sold at the market in a certified kitchen.

My previous customers still demanded my original products, including the cute packaging, so I spent at least one morning a week indulging them. Their cats had benefitted from me learning how to add vitamins and other goodies to make the food more nutritious.

I’d already been up for hours cooking and packaging my Chicken & Sage Indulgence. The herbal smell bothered Elliott and my dad, so I liked to get the kitchen aired out before they even woke up. Trouble absolutely loved that recipe–she’d come running the moment the sage hit the sizzling olive oil and yelled at me to give her tidbits the whole time I was cooking. When I was done with production, I switched to trying new recipes.

My phone had a message from my best friend, Lani, but I had to finish up the chicken liver curry dish before calling her back. I’d also received an alert that someone had given my business a review on SDHelp. I clicked over to the site and saw that a J. Greene had given me one star!

I opened the app to read the review. I bought this cat food at the local flea market—

Flea market? It’s a farmers’ market, idiot. There’s a big difference. I read on.

I had high hopes for this locally-produced, organic cat food, but my cat took one bite and walked away. I couldn’t taste it–even I don’t love my cat that much–but I sniffed it and it smelled awful. A combination of chemicals and rotten meat. Will never buy again.

What? That was impossible. I’d never had a bad review like this. Once someone complained about the price, but I’d never be able to compete price-wise with the big guys. What should I do? Ignore it? Contact Mr. J. Greene and offer to replace it?

I put a few pieces of curried chicken into the refrigerator to cool while I mentally ran through my process. Since my dad got sick, I hadn’t always been in the commercial kitchen the two mornings a week I could afford to rent, relying on my cook who always followed my instructions meticulously. Could something have gone wrong with one batch? But then I would hear from more than one customer. I clicked on the website to see if anyone had left a complaint there. Nothing. I took a deep breath. Maybe it was an isolated incident. Or total bull.

To reassure myself, I turned to the page that had testimonials from my customers. So many of them noted how much healthier their cats were because they ate Meowio food.

“Mom!” Elliott yelled as he ran down the stairs, landing at the bottom with a thud. My son rarely did anything quietly.

I met him in the hall while my dad silenced the TV and stuck his head out to see what was going on.

“I got a callback for Horton!” Elliott announced as he threw his arms in the air in triumph and then fell on the floor in a dramatic faint, clutching his phone to his chest.

“That’s awesome,” I said, pushing back the guilt that I’d totally forgotten about his audition for theater summer camp. Starting on Monday, he’d be spending two weeks with a bunch of other drama kids on a musical—his idea of heaven. On the last Friday, the whole camp would perform Seussical the Musical. “Isn’t Horton one of the leads?” The musical incorporated a couple of Dr. Seuss books into one plot including Horton Hears a Who.

Elliott rolled himself up and jumped to his feet, his dark brown hair flopping over one eye. “Yes!”

“Congratulations, kid,” I said, delighted for him. “When’s the audition?”

He clicked on his phone, reading farther down the email he’d received. His face fell. “Uh-oh,” he said. “It’s this Thursday afternoon.”

That was one of my farmers’ market days and my biggest sales day. My best customers knew they could find me every Thursday afternoon in downtown San Diego, selling my cat food with Trouble watching over the booth in her little chef hat. I’d already paid for my prime spot.

I forced a smile. “It’s okay,” I said. “We’ll just go to the market late.”

“I can take him,” my dad called out from the living room.

Elliott’s eyes widened and he shook his head in a silent plea.

Oh man. I had to handle this carefully. “It’s okay, Dad. I love going to Elliott’s auditions,” I said in a light tone. “And he can help me at the market afterward.”

He subsided with a “harrumph.” Normally having my dad drive Elliott might work, but he hadn’t driven much since he got out of the hospital. And this was Elliott’s first time auditioning for the Sunnyside Junior Theater, and he didn’t know anyone. Even when Elliott tried out for his old theater group where he felt comfortable, he had to be managed carefully so he went into his audition feeling confident. And my dad hadn’t been very supportive of anything Elliott did that wasn’t sports-related.

Elliott let out his breath. He and my dad had gotten along on our short visits over the years, but hadn’t found much common ground since we’d moved in. My dad wouldn’t admit to needing help after his second devastating bout with pneumonia. My macho, football-playing father hated being weak and being forced to accept support from the same daughter he’d driven out of the house thirteen years ago.

And he wouldn’t say it out loud, but it was clear he wasn’t happy with Elliott’s fashion choices. Especially the way Elliott shaved one side of his head and allowed the other to grow long. From the photos of my own grunge days in high school, I knew Elliott would regret that look in the future, but he had to make his own fashion mistakes.

“The director sent me the sheet music for ‘Alone in the Universe,’ and I only have two days to learn it. I’m gonna go practice.” Elliott ran back up to his room, taking the stairs a couple at a time.

“Break a leg!” I called after him. I smiled, caught up in his enthusiasm.

Until my dad “harrumphed” again from the living room.

I took a deep breath, determined to let my dad’s bad attitude go. He’s sick, I told myself and headed back to the kitchen.

But he didn’t stop. “I don’t know why you let him do that nonsense,” he said, lighting my simmering anger.

I did a U-turn at the kitchen doorway and stomped into the living room. “What nonsense? Having fun with other kids? Developing his talents? Pursuing a dream?”

My dad scowled. “Singing and dancing’s not preparing him for the future.”

“He’s twelve, Dad,” I said sarcastically. “He has time. And you think playing with a ball on a field prepares him for the future?”

“It sure does,” he said, defensive. “It teaches teamwork. And following the rules. Something both of ya could learn.” He sat back in his chair, and suddenly he seemed smaller in it. Had he lost more weight?

My anger washed out of me. “He loves it, Dad,” I said, my voice calmer. “And there’s a heck of a lot of teamwork going on behind the scenes and on stage.” I’d seen it first-hand during the obligatory volunteering that went along with any kind of youth theater.

He narrowed his eyes, as if trying to figure out if I was just feeling sorry for him. Then he turned the TV sound back on with his remote. Storage Wars characters were trying to goad each other into bidding higher on someone’s junk.

“It’s a good thing my investments are paying off so I can help with his college,” he grumbled as I took a step to the door. “My new fund is up a full twenty percent this month.”

“What?” I asked. “You have investments?”

“Of course I have investments,” he said, bristling again. “You think I’m an idiot?”

“No,” I said. I couldn’t imagine having enough money for “investments.” “You’re helping with Elliott’s college?”

“Of course I am,” he said. “He’s not getting a singing scholarship, is he?”

I gaped at him. That comment had so many levels of insult that I couldn’t think of a retort to cover them all.

Luckily my phone rang before any sound could come out of my mouth. I counted to ten on the way back to the kitchen and answered it.

“Oh. My. God,” Lani said, her voice breaking up a little over her car Bluetooth connection. “I’m gonna kill Piper.”

“Good morning to you too,” I said. Piper was her wife and Lani threatened to kill her about once a week, usually for no good reason.

I pulled out the now cool pieces of chicken curry and put them in Trouble’s dish. She sniffed it, and then took a bite. Her lips curled back as she chewed. Then she spit it out.

Shoot. There goes that recipe. Unless I tried it again with less curry?

“She threw out my latest prototype! On purpose!” I heard Lani’s car engine zoom in the background, as if it was angry at Piper too.

Lani was the owner and creator of Find Your Re-Purpose, an online boutique of unique baby fashions recycled from used clothing. She cut up old clothing, sewed different materials together, added some fabric paint or other touches, and voila! A beautiful, one-of-a-kind, hundred dollar outfit that anyone with too much money could buy for a baby who would most likely spit up on it in less than five minutes.

We’d met years before when she was the costume designer for one of Elliott’s plays, and quickly figured out that she lived in my dad’s neighborhood. After a few sleepless nights of last minute costume adjustments before the show’s opening, we’d become best friends.

“Was it that cape idea you were kicking around?” I asked.

“Yes!” she said. “It was the cutest thing EV-ER!”

I’d had my own doubts about the safety of capes for infants, but had kept them to myself. Since Piper was a pediatrician, I knew she’d step in. “Where are you headed?” I asked, trying to distract her.

“Ventura,” she said. “A thrift shop just got a big donation of clothes from a rich European family who spent the last six months in Malibu. The material has a bunch of cool designs the shop owner has never seen before so he put them aside for me. I can’t wait to see them.”

Ventura was almost four hours from Sunnyside, which meant Lani would be gone most of the day. Since she liked company on her trip, I put her on speaker phone right by the stove, resumed my stirring, and settled in for a long conversation.

“Have you heard from Twomey’s yet?” she asked, with a change in her tone that meant now-it’s-time-for-friendly-nagging. She’d encouraged me to contact the local chain of seven organic food stores offering my cat food products.

“Not yet,” I admitted. In my e-mail, I’d pushed the fact that buying local was all the rage, especially for the kind of people who bought organic products to help save the planet.

Seeing Meowio Batali products on the shelves of that many stores would be a dream come true. But I wasn’t sure how I’d meet any significant increase in demand without hiring more people. And that took money.

I was pretty stretched already—both physically and money-wise. Too bad cloning me wasn’t an option yet. If I had two, maybe three more of me, I could do everything I should be doing.

I changed the subject. “Hey, I finally met my neighbor.”

“That cute chicken farmer?” she asked.

I turned on the frying pan and dribbled in extra virgin olive oil. “How’d you know he was cute?”

“Everyone knows he’s cute,” she said. “He’s also single, keeps to himself and hasn’t dated at all.”

“Good to know,” I said. I told her all about the chicks and the unfortunate poop incident.

“That’s such a meet cute!” she said. “You can tell your grandchildren that story where you fell in love with his chicks first.”

“I think if there’s poop involved, it’s the exact opposite of a meet cute,” I said. “And I really don’t have time to date right now.”

“You know, it’s really a little like Romeo and Juliet, except with your cat and chickens,” she said. “Joss is a Montague and you’re the Cat-ulets.” She giggled at her own joke.

“And you know how they ended up.” I tossed chunks of chicken in the pan. “Hey, did you head out of town on purpose so I couldn’t drag you to my Power Moms trade show?”

“Oh yeah,” she said unapologetically. “It’s the only reason I chose today to drive to freakin’ Ventura. Just to get away from your cult.”

I laughed. The Sunnyside Power Moms, or SPMs for short, was a group of home business owners who worked together to network and support each other. Our leader, Twila Jenkins, got the idea to start the group when the third mom came up to her at the Sunnyside Elementary School playground to invite her to a party at her house. One of those “parties” where the host/salesperson puts out lovely hors d’oeuvres and lots of wine so that her guests, i.e., sales targets, will feel more inclined to buy thirty dollar candles and forty-five dollar candle holders.

Twila had invited me to join after learning about my cat food business.

“You’ll come around,” I said. “The first step was when you suggested your friend Fawn become an SPM. You’re one step closer to becoming One of Us. One of Us.” I chanted that in a low tone a few times until she interrupted me.

“Not a chance,” she said. “Hey! You should manufacture some kind of scandal. That’ll get people interested in your little coven.”

I rolled my eyes, even though she couldn’t see me. “Be nice or I’ll sign you up to host a candle party at your house.”

She gasped dramatically. “A fate worse than death.”