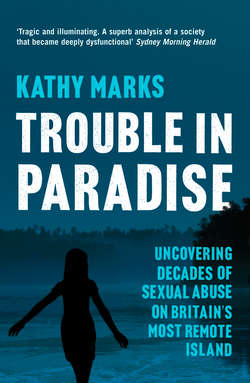

Читать книгу Trouble in Paradise: Uncovering the Dark Secrets of Britain’s Most Remote Island - Kathy Marks - Страница 14

CHAPTER 3 Opening a right can of worms

ОглавлениеWhile exploring my surroundings in those early days before the trials began, I poked my head into the public hall, which doubled as Pitcairn’s courthouse. A familiar figure gazed back at me: Queen Elizabeth II, in a hat and pearls, clasping a bunch of flowers. There were, in all, three photographs of the Queen at the front of the hall, as well as one of the Duke of Edinburgh and one of the royal couple. On the same wall hung a Union Jack, together with a Pitcairn flag and a British coat of arms.

It was an overt display of patriotism of a kind rarely seen nowadays, and it was in striking contrast to the anti-British sentiments expressed at Big Fence, where most of the women seemed to agree with Tania Christian, Steve’s daughter, when she declared that ‘Britain can go to hell as far as I care.’

The reality was that, until Operation Unique started, barely a subversive murmur was heard around Adamstown. Pitcairn was Britain’s last remaining territory in the South Pacific, and its inhabitants were—as visitors often remarked—among Her Majesty’s most loyal subjects. Until not so long ago, ‘God Save the Queen’ was sung at public meetings, school concerts, even the twice-weekly film shows, while the British flag was flown on the slightest pretext. A number of islanders were MBEs, and several, including Steve Christian, Jay Warren and Brian Young, one of the ‘off-island’ accused, had been invited to Buckingham Palace.

Pitcairn’s origins were emphatically anti-British, of course; in Fletcher Christian’s day, there were few acts more heinous than mutiny. So it was an ironic twist when, a couple of decades later, the British Navy became the islanders’ guardian and lifeline. The captains of British warships that patrolled the South Seas in the 19th century, keeping an eye on that corner of Empire, felt responsible for the minuscule territory. They developed a sentimental attachment to the place and stopped there regularly, delivering gifts and supplies. They also found themselves settling disputes and dispensing justice in the fledgling community.

Russell Elliott, the commander of HMS Fly, who visited in 1838 after a difficult decade for the islanders, is recalled with particular fondness. Following John Adams’ death in 1829, the Pitcairners had emigrated to Tahiti, where many of them died of unfamiliar diseases. The rest, after limping home, spent five years under the despotic rule of an English adventurer, Joshua Hill, who convinced them that he had been sent out from Britain to govern them. When Hill left, they were then terrorised by American whalers, who threatened to rape the women and taunted the locals for having ‘no laws, no authority, no country’. Demoralised, the islanders begged Elliott to place them under the protection of the British flag, and he agreed, drawing up a legal code and constitution that gave women the vote for possibly the first time anywhere.

Pitcairn was now British, although for the next 60 years its only connection with the mother country was to be the visiting navy ships. In 1856, concerned about overpopulation, the islanders decamped again, this time to the former British penal colony of Norfolk Island; however, a few families returned, and the population—the origin of the modern community—climbed back to pre-Norfolk levels. Then in 1898 Pitcairn was taken under the wing of the Western Pacific High Commission, based in Fiji, which oversaw British colonies in the region. The WPHC did not trouble itself greatly with its newest acquisition: during a half-century of administrative control, only one High Commissioner visited—Sir Cecil Rodwell, who turned up unannounced in 1929.

In the meantime, the warships stopped calling, although the vacuum was partly filled, following the opening of the Panama Canal, by passenger liners. The captains and pursers of the merchant fleet took over the Royal Navy’s paternal role, ordering provisions for the islanders, carrying goods and passengers for free, and donating items from their own stores.

With the liners came emigration, and intermarriage with New Zealanders. While strong ties were forged between Pitcairn and New Zealand, the relationship with Britain remained fundamental, and one of the colony’s proudest hours came in 1971, when the Duke of Edinburgh and Lord Mountbatten arrived on the Royal Yacht Britannia and were transported to shore in a longboat flying the Union Jack from its midships. Official visits, to the disappointment of the locals, continued to be fleeting and infrequent, though.

There were, obviously, practical obstacles hindering more effective colonial scrutiny. Pitcairn, 3350 miles from Fiji, was hard to get to and even harder to get away from. In order to visit for 11 days in 1944, Harry Maude, a Fiji-based British official, had to be away from home for nearly six months. Communications were also primitive. Until 1985 the only way to contact the island was to send a radio telegram by Morse code.

But logistics were not the only issue. Pitcairn was tiny and remote, with no resources worth exploiting, and—unlike, say, the Falkland Islands in the South Atlantic—it was of no strategic importance. When responsibility for the island was transferred from Fiji to New Zealand in 1970, the British Foreign Office reassured the High Commissioner to Wellington, who would now be supervising the colony, that ‘the duties of the Governor of Pitcairn are not onerous’.

If recent governors heard that statement, they would sigh. In the past, their role as the Queen’s representative on Pitcairn was mainly ceremonial, although they did have the power to pass laws and override the local council. But since allegations of widespread sexual offending came to light, the island has taken up an inordinate amount of their time.

While the scandal broke in 2000, the first hint of it actually came in 1996, with an incident that not only foreshadowed what was to follow, but set off a chain of events that led inexorably to Operation Unique, and the women of Pitcairn breaking their silence. An 11-year-old Australian girl living on the island with her family—let us call her Caroline*—accused Shawn Christian, Steve’s youngest son, of rape. Her father reported it to the Foreign Office, and Kent Police, based in southeast England, offered to investigate.

Dennis McGookin, a freshly promoted detective superintendent and genial ex-rugby player, was given the case. Accompanied by Peter George, an astute detective sergeant, he flew to Auckland in September 1996, where the pair met Leon Salt, the Pitcairn Commissioner, and the British official in charge of servicing the practical needs of the remote territory. (Among other things, the Commissioner organises the delivery of supplies.) The three men travelled to Pitcairn on a container ship, the America Star; arriving in a big swell, they descended the ship’s wildly swinging Jacob’s ladder into the waiting longboat.

Despite Pitcairn having been a British possession for 160 years, McGookin and George were the first British police to set foot there. They were nervous about their reception; yet the islanders, including 20-year-old Shawn, could not have been friendlier. Shawn readily admitted to having sex with Caroline, saying that it had been consensual. He showed them love letters from her, and even escorted them to the sites of their encounters, which included the church.

Caroline’s family had already left the island. She had been questioned by police in New Zealand, and was said to be very tall for her age, physically mature and ‘quite streetwise’. She had made the rape allegation after her parents caught her coming home late. Despite her age, the detectives decided just to caution Shawn for under-age sex.

The inquiry was over in a day, but the Englishmen had to wait to be picked up by a chartered yacht from Tahiti. They resolved to spend their time addressing the issue of law enforcement.

Pitcairn had never had independent policing. The island, theoretically, policed itself. The Wellington-based British Governor appointed a police officer, and the locals elected a magistrate, who was the political leader as well as handling court cases. Until Dennis McGookin and Peter George appeared, the only law was another islander.

The police officer in 1996 was Meralda Warren, a sparky, extrovert woman in her mid-30s. (Meralda was one of the vocal participants at the Big Fence meeting.) While she was bright, Meralda had no qualifications for the position, nor had she received any training. ‘Everyone on the island had a job, and that just happened to be hers,’ says McGookin. Meralda was also related to nearly everyone in the community. If a crime was committed, she might have to arrest her father, or her brother, or one of her many cousins.

History indicated, though, that she was unlikely to find herself in that delicate situation. Her predecessor, Ron Christian, who had been the police officer for five years, had never made a single arrest. Neither had the two previous incumbents, of seven and 21 years’ service respectively. No one had been arrested since the 1950s. The Pitcairners, it seemed, were extraordinarily law-abiding. All Meralda did was issue driving licences and stamp visitors’ passports. To be fair, that was all her predecessors had done.

The magistrate in 1996 was Meralda’s elder brother, Jay, later to go on trial himself. Jay, who was on the longboat when we arrived, had occupied the post for six years. Like Meralda, he had no qualifications or training, and was related to nearly everyone on the island. That could have been tricky, but fortunately for Jay, not a single court case had taken place during his time in office. And previous magistrates had been similarly blessed. The Adamstown court had not sat for nearly three decades.

Not that the locals would have feared the prospect of jail. The size of a garden shed and riddled with termites, the prison—a white wooden building—had never held a criminal. Lifejackets and building materials were stored in its three cells.

The British detectives were unimpressed with Meralda and Jay. According to Peter George, whom I interviewed in the Kent Police canteen in Maidstone in 2005, ‘It was glaringly obvious, bluntly speaking, that their standard of policing was not really adequate.’

When the police left Pitcairn at the end of their ten-day stay, the islanders, including Shawn Christian, waved them off at the jetty. Soon afterwards, the Governor, Robert Alston, wrote a letter to the Chief Constable of Kent Police, David Phillips. Thanks to McGookin and George, he said, the matter—which ‘had the potential to turn into a long, drawn-out and complicated legal case’—had been satisfactorily resolved. Alston added that the visit had ‘had a salutary effect on the islanders and one which will remain with them for a long time’. As a token of gratitude, he sent Phillips a Pitcairn coat of arms, to be displayed at Kent Police headquarters.

Dennis McGookin was not so convinced about the salutary effect. Back in London, he informed the Foreign Office that the island needed to be properly policed. Britain was not prepared to fund a full-time police officer for a community of a few dozen people. Instead, it decided to recruit a community constable to travel to Pitcairn periodically and train the local officer.

In 1997 Gail Cox, who had been with Kent Police for 17 years, was selected for the job. Cox was easygoing and gregarious; she had worked in the traffic section, in schools liaison and on general patrol duties. The Daily Telegraph newspaper, which interviewed her before she left, reported that she was ‘a practised hand at dealing with pub brawls and squabbles between neighbours’, and ‘highly regarded for her ability to defuse situations before they turn nasty’. Cox told the paper that ‘if the line needs to be drawn, it will be drawn, and I am not frightened to draw it’. Those words were to prove prophetic.

Leon Salt, the Auckland-based Commissioner, accompanied Gail Cox to the island and introduced her to the locals. ‘I put on this jokey persona, and they seemed to like that,’ she told me when I met her in Auckland in 2006. ‘They were very accepting of me. I became part of the community.’

Cox spent 12 weeks on Pitcairn, and established a good rapport with the islanders—perhaps too good. ‘A lot of people are romanced by the place, and I fell for it,’ she says. ‘I saw the community through rose-coloured glasses. I thought it was this really idyllic place, and everybody was really nice.’

The Englishwoman was not scheduled to go back to the island until 1999. Between her visits, Pitcairn underwent some changes. A new Deputy Governor, Karen Wolstenholme, was appointed. Wolstenholme took more interest in the place than some previous incumbents, and visited soon after taking up her post. Another fresh face was Sheils Carnihan, a forthright Scot brought up in New Zealand, who started teaching at the school in early 1998.

Carnihan and her husband, Daniel, had been attracted by the idea of living in such an isolated spot. But they found life on the island numbingly ordinary. ‘All the stuff we were told about it being such a wonderful, caring place turned out to be rubbish,’ she told me in 2005. ‘There’s no real community spirit. And it’s not exotic: it’s like any small town. The only difference is you can’t escape.’

From the start, the teacher had a nagging sense that something was ‘not quite right’ with the children. Six- to eight-year-olds in her class talked about boyfriends and girlfriends in a way that seemed, to her, precocious. When Carnihan’s own family got to Adamstown, a boy slightly younger than her 11-year-old daughter, Hannah, told the girl, ‘You’re mine.’ Another boy said the same thing to Carnihan’s other daughter, nine-year-old Adie.

About halfway through her two-year posting, she overheard a snippet of conversation between two schoolgirls, aged 11 and 13, who were sitting on a verandah outside the classroom. ‘You’ll be 12 next week, you know you’ll be old enough for it?’ the older pupil asked her friend.

From what she had seen and heard, Sheils Carnihan already suspected that girls on Pitcairn were considered ‘fair game’ once they turned 12. This little exchange seemed to confirm that. ‘I was appalled,’ she says. ‘The older girl knew her friend would be expected to have sex. She was making sure she understood what her birthday meant.’

Carnihan was particularly worried about two 13-year-old girls, Belinda and Karen, who seemed extremely troubled. They would ‘talk about sexual things and then giggle and be secretive, or make quite blunt sexual comments’, she says. Soon after the teacher’s family arrived, Belinda jumped onto Daniel’s knee and snuggled up to him in a suggestive fashion.

Once Carnihan had occasion to reprimand Karen for bullying, and the girl’s emotional reaction startled her. ‘She was really angry with me, she was crying and told me that I didn’t understand. She said I didn’t know what it was like to be made to be friends with someone or else they would beat me up.’ Perturbed by these incidents, she confided in Meralda Warren, the police officer, and in the Seventh-day Adventist pastor, John Chan, the only other outsider. Meralda, she says, dismissed her concerns, while Chan’s response was that ‘the morals [on Pitcairn] are quite loose, but you don’t do anything about these things’.

During Sheils Carnihan’s stay, Chan, an Australian, was succeeded by a South African-born pastor, Neville Tosen. Before long, Tosen came to share her unease. ‘But we didn’t know what to do about it,’ she says. ‘We didn’t have any evidence. It was just a gut feeling. And we didn’t feel we could ask the girls yet.’

Even as Carnihan agonised about what to do, her own daughters were forming friendships that would be crucial to this case. Hannah and Adie got to know Belinda and Karen, as well as other girls, and went on camping trips with them around the island. During those trips, the adolescents shared their secrets.

Just as for the Carnihans, Pitcairn was not what Neville Tosen had expected. Brought up on tales of a beacon of faith in the Pacific, he had been looking forward to ministering to a community of committed Adventists. However, when he arrived in late 1998 with his wife, Rhonda, he discovered that only a few people went to church—and they were not exactly glowing advertisements for the religion they professed to practise. Tosen was dismayed to learn that adultery was rife, and that churchgoers were also involved in dubious financial dealings. He delivered a few blunt sermons, ‘and we weren’t too popular as a result’, he says. ‘No one had ever told Church members to pull their socks up before. It caused quite a stir. But nothing changed.’

One islander warned him, ‘There’s more to come.’ And Tosen feared that he knew what the man meant. ‘I’ve been a teacher most of my life, and we immediately picked up mood swings,’ he says. ‘One day a certain student will be friendly to you, the next day totally withdrawn. It took me three months. I said, “Wait a minute, these kids are being abused.” When I tried to talk about it, everyone just clammed up, including the kids themselves.’

He and Carnihan agreed to keep a careful eye on the situation; meanwhile, Tosen examined the birth records that were kept in the island secretary’s office. They revealed a pattern: most Pitcairn women had their first child between 12 and 15. The pastor, who spoke to me at his home in Queensland in 2005, raised the subject at a meeting of the island council. One councillor, Tom Christian, who had four daughters, replied, ‘The age of consent has always been 12, and it’s never hurt them.’ Neville Tosen, who had worked all over the Pacific, says, ‘I remember getting quite hot and saying that even the Kanakas of Western Guinea had 16 as an age of consent. Tom got very angry. He called me a racist, and accused me of interfering in island politics.’

Tosen went on, ‘Steve [Christian] also spoke up, saying it was their Tahitian culture and sometimes the girls couldn’t even wait until they were 12. Everyone else at the meeting was very quiet, including Jay, who was mayor then. The only person who supported me was Brenda [Steve’s sister]. She said, “Any man that does that to a 12-year-old deserves to be knackered.”’

When Gail Cox returned to Pitcairn in October 1999 to conduct her second block of training, she found a community at war with itself. Things were very different from her first visit, and she was different, too. Dennis McGookin, her boss, had instructed her to be a police officer, not the islanders’ friend.

The first problem she had to deal with was theft, particularly of government property, which she discovered was widespread and had been going on for years. Diesel fuel was siphoned off into quad bike tanks; timber, roofing iron and fuse boxes vanished as soon as they were unloaded at the wharf; cement for the slipway ended up as a swimming pool in someone’s garden. Electrical equipment and a computer had been stolen. People jokingly referred to one Adamstown home, which was built entirely from pilfered materials, as ‘Government House’. ‘They don’t see it as stealing,’ one outsider told me later. ‘In their minds, everything that arrives on the island is Pitcairn property.’

British officials ordered the policewoman to crack down. She questioned all of the islanders, and nearly everyone, even the elderly folk, owned up to something. One man confessed to stealing NZ$20,000 (£7,500) from the co-operative store. At the suggestion of diplomats in Wellington, Cox offered the locals an amnesty, which they accepted. ‘But they weren’t happy with me challenging them like that,’ she says.

Six weeks or so after Gail Cox returned, Sheils Carnihan’s two-year posting was up. Two days before the family left, 13-year-old Hannah spoke to her mother, disclosing the explosive information that Belinda and Karen, her friends on the island, had confided months earlier. Both girls, allegedly, had been sexually assaulted by Randy Christian, the burly 25-year-old who was Steve’s middle son. Carnihan straight away told Gail Cox, who notified British diplomats in Wellington as well as the Commissioner, Leon Salt.

According to Hannah, Belinda, in particular, was ‘dying to tell’ her mother about Randy, but could not summon up the courage. She even begged her friends to speak to her mother on her behalf, and wrote her a letter, which she then burnt. Belinda was anxious about damaging the friendship between her family and Randy’s, and was sure her mother would not believe her. Hannah told Sheils, ‘She wanted to write to her mum saying what had happened, and that she wanted it to stop. I mean, if her mum knew, maybe it would.’ To which Neville Tosen comments, ‘How the mother didn’t already know about it—I’ve never answered that question. Because from my rather limited access to the girl, I was aware that she’d been interfered with.’

Gail Cox was supposed to leave in late November, on the same ship as the Carnihans, but agreed to stay on longer to deal with the fallout from the thieving revelations. By chance, then, she was still on Pitcairn when Ricky Quinn, a visitor from New Zealand, turned up.

The step-grandson of Vula Young, one of Pitcairn’s matriarchs, Quinn struck Pitcairn like a tropical storm. A good-looking 23-year-old, he had past convictions for possession of LSD, morphine and heroin, which, to the local teenagers, gave him an exciting aura of danger. Quinn had brought with him a stash of marijuana, and he slotted straight in with the minority of islanders who formed the ‘drinking crowd’.

A visiting policewoman on the alert; a handsome newcomer with drugs in his pocket; young girls tired of being preyed upon and itching to talk. All the elements were in place. Now all that was needed was the spark.

The drinkers got together most Friday nights. Two weeks before Christmas, Pawl Warren had a party. Most of the young people on the island attended. They stole some alcohol from their parents, and also some Valium tablets.

Gail Cox was still awake at 1.10 a.m. when Dave Brown, one of the partygoers, knocked on her door. ‘There’s trouble at Pawl’s house,’ Dave announced. At Pawl’s, Cox found several frightened and sobbing youngsters, who admitted that they had been drinking. The police officer went on to Belinda’s house, where Belinda and Karen had taken refuge; once inside, she got the feeling that Belinda wanted to tell her something. But when Cox tried to speak to her, the teenager’s mother stood up and blocked out her husband, who was lying behind her. ‘Not now,’ she mouthed.

Belinda’s mother took Cox aside and told her what the two 15-year-olds, both very distressed, had confided in her. They had been sexually assaulted by Ricky Quinn—and also, in the past, as Hannah had signalled, by Randy Christian. (A third girl, 12-year-old Francesca, had accused Quinn of similar behaviour.)

At 3 a.m. Gail Cox telephoned Dennis McGookin. It was Saturday daytime in England, and he was on his way to watch his favourite rugby team, Gillingham. Cox explained that she needed a specially trained officer to take a complaint from a child. ‘I knew that wasn’t practicable,’ he told me over a pub lunch in Kent in 2005. ‘I told her to take down a detailed statement, making sure an adult was present, and then fax that over to me.’

Cox also emailed Leon Salt to inform him about the weekend’s events, including the allegations against Randy. As I later found out, Salt’s response was swift. ‘If we dig into this, we’ll open a right can of worms, and we’ll have every man on Pitcairn locked up for life,’ he warned her.

* The names of all victims in this book have been changed.