Читать книгу Tell the Machine Goodnight - Katie Williams - Страница 6

The Happiness Machine Apricity (archaic): the feeling of sun on one’s skin in the winter

ОглавлениеThe machine said the man should eat tangerines. It listed two other recommendations as well, so three in total. A modest number, Pearl assured the man as she read out the list that had appeared on the screen before her: one, he should eat tangerines on a regular basis; two, he should work at a desk that received morning light; three, he should amputate the uppermost section of his right index finger.

The man—in his early thirties, by Pearl’s guess, and pinkish around the eyes and nose in the way of white rabbits or rats—lifted his right hand before his face with wonder. Up came his left, too, and he used its palm to press experimentally on the top of his right index finger, the finger in question. Is he going to cry? Pearl wondered. Sometimes people cried when they heard their recommendations. The conference room they’d put her in had glass walls, open to the workpods on the other side. There was a switch on the wall to fog the glass, though; Pearl could flick it if the man started to cry.

“I know that last one seems a bit out of left field,” she said.

“Right field, you mean,” the man—Pearl glanced at her list for his name, one Melvin Waxler—joked, his lips drawing up to reveal overlong front teeth. Rabbitier still. “Get it?” He waved his hand. “Right hand. Right field.”

Pearl smiled obligingly, but Mr. Waxler had eyes only for his finger. He pressed its tip once more.

“A modest recommendation,” Pearl said, “compared to some others I’ve seen.”

“Oh sure, I know that,” Waxler said. “My downstairs neighbor sat for your machine once. It told him to cease all contact with his brother.” He pressed on the finger again. “He and his brother didn’t argue or anything. Had a good relationship actually, or so my neighbor said. Supportive. Brotherly.” Pressed it. “But he did it. Cut the guy off. Stopped talking to him, full stop.” Pressed it. “And it worked. He says he’s happier now. Says he didn’t have a clue his brother was making him unhappy. His twin brother. Identical even. If I’m remembering.” Clenched the hand into a fist. “But it turned out he was. Unhappy, that is. And the machine knew it, too.”

“The recommendations can seem strange at first,” Pearl began her spiel, memorized from the manual, “but we must keep in mind the Apricity machine uses a sophisticated metric, taking into account factors of which we’re not consciously aware. The proof is borne out in the numbers. The Apricity system boasts a nearly one hundred percent approval rating. Ninety-nine point nine seven percent.”

“And the point three percent?” The index finger popped up from Waxler’s fist. It just wouldn’t stay down.

“Aberrations.”

Pearl allowed herself a glance at Mr. Waxler’s fingertip, which appeared no different from the others on his hand but was its own aberration, according to Apricity. She imagined the fingertip popping off his hand like a cork from a bottle. When Pearl looked up again, she found that Waxler’s gaze had shifted from his finger to her face. The two of them shared the small smile of strangers.

“You know what?” Waxler bent and straightened his finger. “I’ve never liked it much. This particular finger. It got slammed in a door when I was little, and ever since …” His lip drew up, revealing his teeth again, almost a wince.

“It pains you?”

“It doesn’t hurt. It just feels … like it doesn’t belong.”

Pearl tapped a few commands into her screen and read what came back. “The surgical procedure carries minimal risk of infection and zero risk of mortality. Recovery time is negligible, a week, no more. And with a copy of your Apricity report—there, I’ve just sent that to you, HR, and your listed physician—your employer has agreed to cover all relevant costs.”

Waxler’s lip slid back down. “Hm. No reason not to then.”

“No. No reason.”

He thought a moment more. Pearl waited, careful to keep her expression neutral until he nodded the go-ahead. When he did, she tapped in the last command and, with a small burst of satisfaction, crossed his name off her list. Melvin Waxler. Done.

“I’ve also recommended that your workpod be reassigned to the eastern side of the building,” she said, “near a window.”

“Thank you. That’ll be nice.”

Pearl finished with the last prompt question, the one that would close the session and inch her closer to her quarterly bonus. “Mr. Waxler, would you say that you anticipate Apricity’s recommendations will improve your overall life satisfaction?” This phrasing was from the updated training manual. The question used to be Will Apricity make you happier? but Legal had decided that the word happier was problematic.

“Seems like it could,” Waxler said. “The finger thing might lower my typing speed.” He shrugged. “But then there’s more to life than typing speed.”

“So … yes?”

“Sure. I mean, yes.”

“Wonderful. Thank you for your time today.”

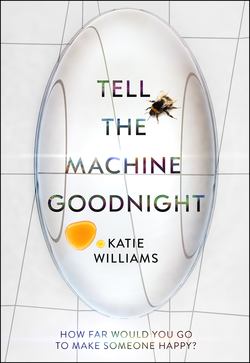

Mr. Waxler rose to go, but then, as if struck by an impulse, he stopped and reached out for the Apricity 480, which sat on the table between them. Pearl had just last week been outfitted with the new model; sleeker than the Apricity 470 and smaller, too, the size of a deck of cards, the machine had fluted edges and a light gray casing that reflected a subtle sheen, like the smoke inside a fortune-teller’s ball. Waxler’s hand hovered over it.

“May I?” he said.

At Pearl’s nod, he tapped the edge of the Apricity with the tip of the finger now scheduled to be amputated in—confirmations from both HR and the doctor’s office had already arrived on Pearl’s screen—a little over two weeks. Was it Pearl’s imagination or did Mr. Waxler already stand a bit taller, as if an invisible yoke had been lifted from his shoulders? Was the pink around his eyes and nose now matched by a healthy flush to the cheek?

Waxler paused in the doorway. “Can I ask one more thing?”

“Certainly.”

“Does it have to be tangerines, or will any citrus do?”

PEARL HAD WORKED AS A CONTENTMENT TECHNICIAN for the Apricity Corporation’s San Francisco office since 2026. Nine years. While her colleagues hopped to new job titles or start-ups, Pearl stayed on. Pearl liked staying on. This was how she’d lived her life. After graduating college, Pearl had stayed on at the first place that had hired her, working as a nocturnal executive assistant for brokers trading in the Asian markets. After having her son, she’d stayed on at home until he’d started school. After getting married to her college boyfriend, she’d stayed on as his wife, until Elliot had an affair and left her. Pearl was fine where she was, that’s all. She liked her work, sitting with customers who had purchased one of Apricity’s three-tiered Contentment Assessment Packages, collecting their samples, and talking them through the results.

Her current assignment was a typical one. The customer, the up-and-coming San Francisco marketing firm !Huzzah!, had purchased Apricity’s Platinum Package in the wake of an employee death, or, as Pearl’s boss had put it, “A very un-merry Christmas and to one a goodnight!” Hours after the holiday party, a !Huzzah! copywriter had committed suicide in the office lounge. The night cleaning service had found the poor woman, but hours too late. Word of the death had made the rounds, of course, both its cause and its location. !Huzzah!’s January reports noted a decrease in worker productivity, an accompanying increase in complaints to HR. February’s reports were grimmer still, the first weeks of March abysmal.

So !Huzzah! turned to the Apricity Corporation and, through them, Pearl, who’d been brought into !Huzzah!’s office in SoMa to create a contentment plan for each of the firm’s fifty-four employees. Happiness is Apricity. That was the slogan. Pearl wondered what the dead copywriter would think of it.

The Apricity assessment process itself was noninvasive. The only item that the machine needed to form its recommendations was a swab of skin cells from the inside of the cheek. This was Pearl’s first task on a job, to hand out and collect back a cotton swab, swipe a hint of captured saliva across a computer chip, and then fit the loaded chip into a slot in the machine. The Apricity 480 took it from there, spelling out a personalized contentment plan in mere minutes. Pearl had always marveled at this: to think that the solution to one’s happiness lay next to the residue of the bagel one had eaten for breakfast!

But it was true. Pearl had sat for Apricity herself and felt its effects. Though for most of Pearl’s life unhappiness had only ever been a mild emotion, not a cloud overhead, as she’d heard others describe it, surely nothing like the fog of a depressive, none of this bad weather. Pearl’s unhappiness was more like the wisp of smoke from a snuffed candle. A birthday candle at that. Steady, stalwart, even-keeled: these were the words that had been applied to her since childhood. And she supposed she looked the part: dark hair cropped around her ears and neck in a tidy swimmer’s cap; features pleasing but not too pretty; figure trim up top and round in the thighs and bottom, like one of those inflatable dolls that will rock back up after you punch it down. In fact, Pearl had been selected for her job as an Apricity technician because she possessed, as her boss had put it, “an aura of wooly contentment, like you have a blanket draped over your head.”

“You rarely worry. You never despair,” he’d gone on, while Pearl sat before him and tugged at the cuffs of the suit jacket she’d bought for the interview. “Your tears are drawn from the puddle, not the ocean. Are you happy right now? You are, aren’t you?”

“I’m fine.”

“You’re fine! Yes!” he shouted at this revelation. “You store your happiness in a warehouse, not a coin pouch. It can be bought cheap!”

“Thank you?”

“You’re very welcome. Look. This little guy likes you”—he’d indicated the Apricity 320 in prime position on his desk—“and that means I like you, too.”

That interview had been nine years and sixteen Apricity models ago. Since then Pearl had suffered dozens more of her boss’s vaguely insulting metaphors and had, more importantly, seen the Apricity system prove itself hundreds—no, thousands of times. While other tech companies shriveled into obsolescence or swelled into capitalistic behemoths, the Apricity Corporation, guided by its CEO and founder, Bradley Skrull, had stayed true to its mission. Happiness is Apricity. Yes, Pearl was a believer.

However, she was not so naïve as to expect that everyone else must share her belief. While Pearl’s next appointment of the day went nearly as smoothly as Mr. Waxler’s—the man barely blinked at the recommendation that he divorce his wife and hire a series of reputable sex workers to fulfill his carnal needs—the appointment after that went unexpectedly poorly. The subject was a middle-aged web designer, and though Apricity’s recommendation seemed a minor one, to adopt a religious practice, and though Pearl pointed out that this could be interpreted as anything from Catholicism to Wicca, the woman stormed out of the room, shouting that Pearl wanted her to become weak minded, and that this would suit her employer’s purposes quite well, wouldn’t it, now? Pearl sent a request to HR to schedule a follow-up appointment for the next day. Usually these situations righted themselves after the subject had had time to contemplate. Sometimes Apricity confronted people with their secret selves, and, as Pearl had tried to explain to the shouting woman, such a passionate reaction, even if negative, was surely a sign of just this.

Still, Pearl arrived home deflated—the metaphorical blanket over her head feeling a bit threadbare—to find her apartment empty. Surprisingly, stunningly empty. She made a circuit of the rooms twice before acknowledging that Rhett had, for the first time since he’d come back from the clinic, left the house of his own volition. A shiver ran through her and gathered, buzzing, beneath each of her fingernails. She fumbled with her screen, pulling it from the depths of her pocket and unfolding it.

“Just got home,” she spoke into it.

k, came the eventual reply.

“You’re not here,” she said. What she wanted to say: Where the hell are you?

fnshd hw wnt out came back.

“Be home in time for dinner.”

The alert that her message had been sent and received sounded like her screen had heaved a deep mechanical sigh.

Her apartment was in the outer avenues of the city’s Richmond District. You could walk to the ocean, could see a corner of it even, gray and tumbling, if you pressed your cheek against the bathroom window and peered left. Pearl pictured Rhett alone on the beach, walking into the surf. But no, she shouldn’t think that way. Rhett’s absence from the apartment was a good thing. It was possible—wasn’t it?—that he’d gone out with friends from his old school. Maybe one of them had thought of him and decided to call him up. Maybe Josiah, who’d seemed the best of the bunch. He’d been the last of them to stop visiting, had written Rhett at the clinic, had once pointed to one of the dark bruises that had patterned Rhett’s limbs and said, Ouch, so sadly and sweetly it was as if the bruise were on his own arm, the blood pooling under the surface of his own unmarked skin.

Pearl said it now, out loud, in her empty apartment.

“Ouch.”

Speaking the word brought no pain.

To pass the hour until dinner, Pearl got out her latest modeling kit. The kits had been on Apricity’s contentment plan for Pearl. She was nearly done with her latest, a trilobite from the Devonian period. She fitted together the last plates of the skeleton, using a tiny screwdriver to turn the tinier screws hidden beneath each synthetic bone. This completed, she brushed a pebbled leathery material with a thin coat of glue and fitted the fabric snugly over the exoskeleton. She paused and assessed. Yes. The trilobite was shaping up nicely.

When it came to her models, Pearl didn’t skimp or rush. She ordered high-end kits, the hard parts produced with exactitude by a 3-D printer, the soft parts grown in a brew of artfully spliced DNA. Once again, Apricity had been correct in its assessment. Pearl felt near enough to happiness in that moment when she sliced open the cellophane of a new kit and inhaled the sharp smell of its artifice.

Before the trilobite, she’d made a Protea cynaroides, common name king protea, the model of a plant that, as Rhett was quick to point out, wasn’t actually extinct. She could have grown a real king protea in the kitchen window box, the one that got weak light from the alley. But Pearl didn’t want a real king protea. Rather, she didn’t want to grow a king protea. She wanted to build the plant piece by piece. She wanted to shape it with her own hands. She wanted to feel something grand and biblical: See what I wrought? The king protea had bloomed among the dinosaurs. Think of that! This blossom crushed under their ancient feet.

The Home Management System interrupted Pearl’s focus, its soft librarian tones alerting her that Rhett had just entered the lobby. Pearl gathered her modeling materials—the miniature brushes, the tweezers with ends as fine as the hairs they placed, and the amber bottles of shellac and glue—so that all would be put away before Rhett reached the apartment door. She didn’t want Rhett to catch her at her hobby because she knew he’d smirk and needle her. Dr. Frankenstein? he’d announce in his flat tone, curiously like a PA system even when he wasn’t imitating one. Paging Dr. Frankenstein. Monster in critical condition. Monster code blue! Code blue! Stat! And while Rhett’s jibes didn’t bother Pearl, she also didn’t think it was especially good for him to be given opportunities to act unpleasant. He didn’t need opportunities anyway. Her son was a self-starter when it came to unpleasantness. No, she hadn’t thought that.

The sound of the front door, and a moment later, there Rhett was, each of the precious ninety-four pounds of his sixteen-year-old self. It had been cold outside, and she could smell the spring air coming off him, metallic, galvanized. Pearl looked for a flush in his cheeks like the one she’d seen in Mr. Waxler’s, but Rhett’s skin remained sallow; his visible cheekbones were a hard truth. Had he been losing weight again? She wouldn’t ask. After all, Rhett had arrived in the kitchen without prompting, presumably to say hello. She wouldn’t annoy him by asking him where he’d been or, to Rhett’s mind the worst question of them all, the one word: Hungry?

Instead, Pearl pulled out a chair and was rewarded for her restraint when Rhett sat in it with a truculent dip of the head, as if acknowledging she’d scored a point on him. He pulled off his knit cap, his hair a fluff in its wake. Pearl resisted the impulse to brush it down with her hand, not because she needed him to be tidy but because she longed to touch him. Oh how he’d flinch if she reached anywhere near his head!

She got up to search the cupboards, announcing, “I had a horrible day.”

She hadn’t. It’d been, at worst, mildly taxing, but Rhett seemed relieved when Pearl complained about work, eager to hear about the secret strangeness of the people Apricity assessed. The company had a strict client confidentiality policy, authored by Bradley Skrull himself. So technically, contractually, Pearl wasn’t supposed to talk about her Apricity sessions outside of the office, and certainly many of them weren’t appropriate conversation for a teenage boy and his mother. However, Pearl had dismissed all such objections the moment she’d realized that other people’s sadness was a balm for her son’s own powerful and inexplicable misery. So she told Rhett about the man, earlier that day, who’d been unruffled by the suggestion that he exchange his wife for prostitutes, and she told him about the woman who’d shouted at her over the simple suggestion of exploring a religion. She didn’t, however, tell him about Mr. Waxler’s amputated finger, worried that Rhett would take to the idea of cutting off bits of himself. A finger weighed, what, at least a few ounces?

Rhett grinned as Pearl laid the office workers bare, a mean grin, his only grin. When he was little, he’d beamed generously and frequently, light shining through the gaps between his baby teeth. No. That was overstating it. It had simply seemed that way to Pearl, the brilliance of his little-boy smile. “Moff,” he used to call her, and when she’d pointed at her chest and corrected, “Mom?” he’d repeated, “Moff.” He’d called Elliot the typical “Dad” readily enough, but “Moff” Pearl had remained. And she’d thought joyously, foolishly, that her son’s love for her was so powerful that he’d felt the need to create an entirely new word with which to express it.

Pearl went about preparing Rhett’s dinner, measuring out the chalky protein powder and mixing it into the viscous nutritional shake. Sludge, Rhett called the shakes. Even so, he drank them as promised, three times a day, an agreement made with the doctors at the clinic, his release dependent upon this and other agreements—no excessive exercise, no diuretics, no induced vomiting.

“I guess I have to accept that people won’t always do what’s best for them,” Pearl said, meaning the woman who’d shouted at her, realizing only as she was setting the shake in front of her son that this comment could be construed as applying to him.

If Rhett felt a pinprick, he didn’t react, just leaned forward and took a small sip of his sludge. Pearl had tried the nutritional shake herself once; it tasted grainy and falsely sweet, a saccharine paste. How could he choose to subsist on this? Pearl had tried to tempt Rhett with beautiful foods bought from the downtown farmers’ markets and local corner bakeries, piling the bounty in a display on the kitchen counter—grapes fat as jewels, organic milk thick from the cow, croissants crackling with butter. This Rhett had looked at like it was the true sludge.

Many times, Pearl fought the impulse to tell her son that when she was his age, this “disease” was the affliction of teenage girls who’d read too many fashion magazines. Why? she wanted to shout. Why did he insist on doing this? It was a mystery, unsolvable, because even after enduring hours of traditional therapy, Rhett refused to sit for Apricity. She’d asked him to do it only once, and it had resulted in a terrible fight, their worst ever.

“You want to jam something inside me again?” he’d shouted.

He was referring to the feeding tube, the one that—as he liked to remind her in their worst moments—she’d allowed the hospital to use on him. And it had been truly horrible when they’d done it, Rhett’s thin arms batting wildly, weakly, at the nurses. They’d finally had to sedate him in order to get it in. Pearl had stood in the corner of the room, helpless, and followed the black discs of her son’s pupils as they’d rolled up under his eyelids. After, Pearl had called her own mother and sobbed into the phone like a child.

“‘Jam something’?” she said. “Really now. It’s not even a needle. It’s a cotton swab against your cheek.”

“It’s an invasion. You know the word for that, don’t you? Putting something inside someone against their will.”

“Rhett.” She sighed, though her heart was hammering. “It’s not rape.”

“Call it what you want, but I don’t want it. I don’t want your stupid machine.”

“That’s fine. You don’t have to have it.”

Even though he’d won the argument, Rhett had afterward closed his mouth against all food, all speech. A week later he’d been back in the clinic, his second stint there.

“School?” she asked him now.

She fixed her own dinner and began to eat it: a small bowl of pasta, dressed with oil, mozzarella, tomato, and salt. Anything too rich or pungent on her plate and Rhett’s nostrils flared and his upper lip curled in repulsion, as if she’d come to the table dressed in a negligee. So she ate simply in front of him, inoffensively. The ascetic diet had caused her to lose weight. Pearl’s boss had remarked that she’d been looking good lately, “like one of those skinny horses. What are they called? The ones that run. The ones with the bones.” Fine then. Pearl would lose weight if Rhett would gain it. An unspoken pact. An equilibrium. Sometimes Pearl would think back to when she was pregnant, when it was her body that fed her son. She’d told Rhett this once, in a moment of weakness—When I was pregnant, my body fed you—and at this comment he’d looked the most disgusted of all.

But this evening, Rhett seemed to be tolerating things: his nutritional shake, her pasta, her presence. In fact, he was almost animated, telling her about an ancient culture he was studying for his anthropology class. Rhett took his classes online. He’d started when he was at the clinic and continued after he’d returned home, never going back to his quite nice, quite expensive private high school, paid for, it was worth noting, by the Apricity Corporation he disdained. These days, he rarely left the apartment.

“These people, they drilled holes in their skulls, tapped through them with chisels.” There was fascination in Rhett’s flat voice, a PA system announcing the world’s wonders. “The skin grows back over and you live like that. A hole or two in your head. They believed it made it easier for divinity to get in. Hey!” He slammed down his glass, fogged with the remnants of his shake. “Maybe you should suggest that religion to that angry lady. Tap a hole in her head! Gotta bring your chisel to work tomorrow.”

“Good idea. Tonight I’ll sharpen its point.”

“No way.” He grinned. “Leave it dull.”

Pearl knew she must have looked startled because Rhett’s grin snuffed out, and for a moment he seemed almost bewildered, lost. Pearl forced a laugh, but it was too late. Rhett pushed his glass to the center of the table and rose, muttering, “G’night,” and seconds later came the decisive snick of his bedroom door.

Pearl sat for a moment before she made herself rise and clear the table, taking the glass last, for it would require scrubbing.

PEARL WAITED UNTIL an hour after the HMS noted Rhett’s light clicking off before sneaking into his bedroom. She eased the closet door open to find the jeans and jacket he’d been wearing that day neatly folded on their shelf, an enviable behavior in one’s child if it weren’t another oddity, something teenage boys just didn’t do. Pearl searched the clothing’s pockets for a Muni ticket, a store receipt, some scrap to tell her where her son had been that afternoon. She’d already called Elliot to ask if Rhett had been with him, but Elliot was out of town, helping a friend put up an installation in some gallery (Minneapolis? Minnetonka? Mini-somewhere), and he’d said that Valeria, his now wife, would definitely have mentioned if Rhett had stopped by the house.

“He’s still drinking his shakes, isn’t he, dove?” Elliot had asked, and when Pearl had affirmed that, yes, Rhett was still drinking his shakes, “Let the boy have his secrets then, as long as they’re not food secrets, that’s what I say. But, hey, I’ll schedule something with him when I’m back next week. Poke around a bit. And you’ll call me again if there’s anything else? You know I want you to, right, dove?”

She’d said she knew; she’d said she would; she’d said goodnight; she hadn’t said anything—she never said anything—about Elliot’s use of her pet name, which he implemented perpetually and liberally, even in front of Valeria. Dove. It didn’t pain Pearl, not much. She knew Elliot needed his affectations.

Ever since they’d met, back in college, Elliot and his cohort had been running around headlong, swooning and sobbing, backstabbing and catastrophizing, all of this drama supposedly necessary so that it could be regurgitated into art. Pearl had always suspected that Elliot’s artist friends found her and her general studies major boring, but that was all right because she found them silly. They were still doing it, too—affairs and alliances, feuds and grudges long held—it was just that now they were older, which meant they were running around headlong with their little paunch bellies jiggling before them.

The pockets of Rhett’s jeans were empty; so was the small trash basket beneath his desk. His screen, unfolded and set on its stand on the desk, was fingerprint locked, so she couldn’t check that. Pearl stood over her son’s bed in the dark and waited, as she had when he was an infant, her breasts filled and aching with milk at the sight of him. And so she’d stood again over these last two difficult years, her chest still aching but now empty, until she was sure she could see the rise and fall of his breath under the blanket.

After Rhett’s first time at the clinic, when treatment there hadn’t been working, they’d taken him to this place Elliot had found, a converted Victorian out near the Presidio, where a team of elderly women treated the self-starvers by holding them. Simply holding them for hours. “Hug it out?” Rhett had scoffed when they’d told him what he must do. At that point, though, he’d been too weak to resist, too weak to sit upright without assistance. The “treatment” was private, parents weren’t allowed to observe, but Pearl had met the woman, Una, who had been assigned to Rhett. Her arms were plump and liver-spotted with a fine mesh of lines at elbow and wrist, as if she wore her wrinkles like bracelets, like sleeves. Pearl held her politeness in front of her as a scrim to hide the sudden hatred that gripped her. She hated that woman, hated her sagging, capable arms. Pearl had sat here in this apartment, imagining Una, only twenty-two blocks away, holding her son, providing what Pearl should have been able to and somehow could not. Once Rhett had regained five pounds, Pearl had convinced Elliot that they should move him back to the clinic. There he’d lost the five pounds he’d gained and then two more, and though Elliot kept suggesting returning him to the Victorian, Pearl had remained firm in her refusal. “Those crackpots?” she said to Elliot, pretending this was her objection. “Those hippies? No.” No, she repeated to herself. She would do anything for her Rhett, had done anything, but the thought of Una cradling her son, as he gazed up softly—this was what Pearl couldn’t bear. She would hold Una in reserve, a last resort. After leaving the Victorian, Rhett was back in the hospital again and then the terrible feeding tube. But it had worked, eventually it had. Pearl had eked out her son’s recovery pound by pound. Was that where Rhett had been this afternoon? Had he gone to see Una? Had he needed her arms?

A subtle shift of the bedcovers as Rhett’s chest rose, and Pearl slipped out of the room. If she were to sit for Apricity again, she wondered if there’d be a new item listed on her contentment plan: Watch your son breathe. Though, in truth, this practice didn’t make her happy so much as stave off a swell of desperation.

THE NEXT MORNING, the web designer was late for their follow-up appointment. When she finally arrived, she entered in a huff, which Pearl mistook for more of yesterday’s outrage. But once the woman had taken her seat and unwound a long red scarf from her neck, the first thing she did was apologize.

“You probably won’t believe this,” she said, “but I hate it when people yell. I’m not one to raise my voice.”

The woman, Annette Flatte, made her apology in a practical manner with no self-pity or shuffling of blame. She wore the exact same outfit she had the day before, a white T-shirt and tailored gray slacks. Pearl imagined Ms. Flatte’s closet full of identical outfits, fashion an unnecessary distraction.

“Did they tell you about what happened after the Christmas party?” Ms. Flatte said. “Why they brought you in?”

Pearl made a quick calculation and decided that Ms. Flatte would not be the type of person who would consider feigned ignorance a form of politeness. “Your coworker who killed herself? Yes. They told me at the outset. Did you know her?”

“Not really. Copywriting, Design: different floors.” Ms. Flatte opened her mouth, then closed it again, reconsidering. Pearl waited her out. “Some of them are joking about it,” Ms. Flatte finally said.

Pearl was already aware of this. Two employees had made the same joke during their sessions with Pearl: Guess Santa didn’t bring her what she wanted.

“It’s tacky.” Ms. Flatte shook her head. “No. It’s unkind.”

“Unhappiness breeds unkindness,” Pearl said dutifully, one of the lines from the Apricity manual. “Just as unkindness breeds unhappiness.” She reached for something else to say, something not in the manual, something of her own, but the landscape was razed, barren. There was nothing there. Why was there nothing there?

“They’re scared,” she finally said.

“Scared?” Ms. Flatte snorted. “Of what? Her ghost?”

“That someday they might feel that sad.”

Ms. Flatte stared at the scarf in her lap, combing its fringe. When she spoke, it was in a rush: “She wrote something for me once, a little line of copy, or actually poetry. She left it on my desk my first week here.”

“What did it say?”

Ms. Flatte bent down to the bag at her feet. Pearl could see the bones of her skull through the close crop of her hair, could see the curve and divot where spine and skull met. Pearl pictured fitting these pieces together, turning the tiny screws. Ms. Flatte came back up with a pocketbook, and from its coin compartment she extracted a slip of paper. Pearl took the slip carefully between two fingers. It was printed with a computer font designed to imitate hasty cursive.

You will take a long trip and you will be very happy, though alone.

“I looked it up,” Ms. Flatte said. “It’s from an old poem called ‘Lines for the Fortune Cookies.’ And see? Doesn’t it look like the little paper you get inside the cookie? Apparently she did it for everyone on their first week, chose a different line from a different poem. To welcome them. No one else told you about how she did that?”

“They didn’t say.”

Ms. Flatte pressed her lips together.

“The truth is, you were right,” Ms. Flatte said. “Or your machine was anyway. I do need something.” She laid heavily on the last word. “I don’t know about religion. I was raised to distrust it. But … something. This morning—” She stopped.

“This morning?” Pearl prompted.

“The bus takes me through Golden Gate Park, and there’s always these old people out on the lawn doing their tai chi. Today I got out and watched them for a while. That’s why I was late to meet you. Do you think … could that be it? For me, I mean? Do you think that’s what the machine could have meant?”

Pearl pretended to consider the question, already knowing she would deliver the standard reply. “Try and see. With Apricity, there’s no right and wrong. There’s just what works for you.”

Ms. Flatte smiled suddenly and broadly, her whole face changed by it. “Can you imagine?” She laughed. “All those old Chinese people … and me?”

She thanked Pearl, apologizing once more for her outburst the day before, before bending to gather and rewind her long red scarf.

“Ms. Flatte,” Pearl said as the woman stood to go, “one more thing.”

“Yes?”

“Would you say that you anticipate Apricity’s recommendations will improve your overall life satisfaction?”

“What’s that?”

“Will you be happier?” Pearl asked. “Will you … will you be happy?”

Ms. Flatte blinked, as if surprised by the question; then she nodded once, curt but sure. “I think I will.”

Pearl was surprised to feel a flare of … was it disappointment? She watched the gentle nape of Ms. Flatte’s neck as the woman walked from the conference room, and she felt a sudden and ferocious wish that Ms. Flatte would turn around and, as she had the day before, begin to shout.

WHEN SHE RETURNED HOME, Pearl wondered if she’d find the apartment empty again. But no, there was Rhett, in his room at the computer, doing schoolwork, just as he was supposed to be.

“Hey,” he said without turning around.

Pearl was so focused on the delicate wings of his hunched shoulders that it took her a moment to spot the half-finished trilobite set out on his desk.

“Is it okay I took it?” He’d turned and followed her gaze.

“Of course. But it’s not finished yet. It still needs its details: antennae, legs, a topcoat of shellac.” Then, on impulse, “You could help me finish it.”

“Yeah, maybe.” He’d already turned back around.

“This weekend?”

“Maybe.”

Pearl lingered. She wished she could make her departure now, on this promising note, but they had to get it done before Rhett ate (drank) his dinner.

“Rhett? It’s weigh-in day.”

“Yeah, I know,” he said tonelessly. “Just let me finish my paragraph.”

He met her, minutes later, in the bathroom, where he shrugged off his sweatshirt and put it into her waiting hand.

“Pockets,” she said.

He gave her a look but obliged without comment, turning them inside out. It had been his trick in the past to load his pockets with heavy objects. When Pearl nodded, Rhett stepped on the scale. She was not tall, but he was taller than her now, taller still as he stood on the scale. Taller, but he weighed less than her, and she was not a large woman. Rhett stared straight ahead, leaving Pearl to gaze at the number on her own. She felt it, that number. Higher or lower, she felt it every week, as if it affected her body in reverse, lightening her or weighing her down.

“You’ve lost two pounds.”

He stepped off the scale without comment.

“That’s not good, Rhett.”

“It’s a blip.” “It’s not good.”

“You’ve seen me. I’m drinking my shakes.”

“Where were you yesterday?”

He closed his mouth slowly, defiantly. “Nowhere that has anything to do with that number.”

“Look. I’m your mother—”

“And I’m sorry for that.”

“Sorry? Don’t be sorry. I just want you to—” She stopped. What was she saying? She just wanted him to what? She sounded as if she were reading from some sort of script. “We’ll do an extra weigh-in. On Saturday. If it’s just a blip, it’ll be back to normal then.”

“Okay.”

“If it’s not, we’ll call Dr. Singh and adjust the recipe for your shake. He may want us to come in.”

“I said okay.”

DINNER WAS SILENT, except for the deliberate sound of Rhett slurping his shake. Pearl comforted herself by thinking that this was the exact sort of thing teenage boys did, acted purposely obnoxious to get back at you for scolding them. After dinner, she got out a new modeling kit, this one for a particular species of wasp, and began the armature, twisting the wire filaments with her pliers. As usual, Rhett had disappeared to his room directly after dinner. To study for a test, he’d said. Pearl was lost in her work with the wasp, only emerging when she heard a scrape on the tabletop to find Rhett there, returning the trilobite. He stood, as if waiting, his hand still on the model. She couldn’t read his expression.

“It’s fine if you keep it in your room,” she said. “I mean, I’d like you to.”

“But you need to finish it? You said that.”

On impulse, she reached out and grabbed his wrist. It was so thin! You didn’t really know until you’d touched it. She could have circled it with her thumb and finger easily. There was still a bit of the fur on his skin, the silky translucent hair that his body had grown to keep him warm when he’d been at his skinniest. Lanugo, the doctors had called it. They both stared down at her hand on Rhett’s wrist. She knew he was probably horrified; he hated being touched, especially by her. But she couldn’t make herself release it. She stroked the fur with her finger.

“It’s soft,” she murmured.

He didn’t speak, but he also didn’t pull away.

“I wish I could replicate it on one of my models.” She’d spoken without thinking, a bizarre and horrible thing to say.

But Rhett stayed and let her stroke his wrist for a moment longer. Then, something more, he touched it—improbably—to her cheek before extricating himself.

“Goodnight,” he said, and she thought she heard him add, “Moff.” Then he was gone; again, the sound of his bedroom door. Pearl stared at the unfinished trilobite, imagined it swimming through the dark oceans without the benefit of its antennae to guide it, a compact little shell, deadened and blind. Surely he hadn’t said “Moff.”

Pearl stayed up late again, pretending to work on the wasp, but really making unguided twists in the wire, ending up with an improbable creature, one that had never existed, could never exist; evolution would never allow it. She imagined that the creature existed anyway, imagined it covered with fur, with feathers, with scales, with cilia that reacted to the slightest sensation. When the light to Rhett’s room finally shut off, she went down the hall and got a cotton swab from her bag.

Rhett slept on his back with his lips slightly parted, the effect of the sleeping pill she’d crushed into his shake when fixing his dinner. It was easy to slip the swab into his mouth, to run it against his cheek without causing a murmur or stir. Easier than perhaps it should have been, this act that Rhett and the company, both, would consider a violation. The Apricity 480 sat on the kitchen table, small and knowing. Pearl approached it, the cotton swab in her grip. She unwrapped a new chip, the little slip of plastic that would deliver her son’s DNA to the machine.

You will take a long trip and you will be very happy, though alone.

She loaded the chip, fit it into the port, and tapped the command. The Apricity made a slight whirring as it gathered and tabulated its data. Pearl leaned forward. She unfolded her screen and peered into its blank surface, looking to find her answer there, now, in this last moment before it began to glow.