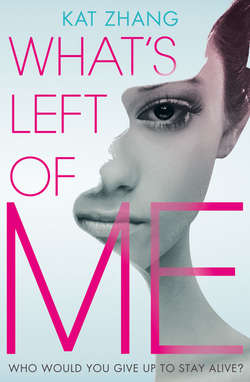

Читать книгу What’s Left of Me - Kat Zhang - Страница 5

Оглавление

ddie and I were born into the same body, our souls’ ghostly fingers entwined before we gasped our very first breath. Our earliest years together were also our happiest. Then came the worries—the tightness around our parents’ mouths, the frowns lining our kindergarten teacher’s forehead, the question everyone whispered when they thought we couldn’t hear.

Why aren’t they settling?

Settling.

We tried to form the word in our five-year-old mouth, tasting it on our tongue.

Set—Tull—Ling.

We knew what it meant. Kind of. It meant one of us was supposed to take control. It meant the other was supposed to fade away. I know now that it means much, much more than that. But at five, Addie and I were still naive, still oblivious.

The varnish of innocence began wearing away by first grade. Our gray-haired guidance counselor made the first scratch.

“You know, dearies, settling isn’t scary,” she’d say as we watched her thin, lipstick-reddened mouth. “It might seem like it now, but it happens to everyone. The recessive soul, whichever one of you it is, will simply … go to sleep.”

She never mentioned who she thought would survive, but she didn’t need to. By first grade, everyone believed Addie had been born the dominant soul. She could move us left when I wanted to go right, refuse to open her mouth when I wanted to eat, cry No when I wanted so desperately to say Yes. She could do it all with so little effort, and as time passed, I grew ever weaker while her control increased.

But I could still force my way through at times—and I did. When Mom asked about our day, I pulled together all my strength to tell her my version of things. When we played hide-and-seek, I made us duck behind the hedges instead of run for home base. At eight, I jerked us while bringing Dad his coffee. The burns left scars on our hands.

The more my strength waned, the fiercer I scrabbled to hold on, lashing out in any way I could, trying to convince myself I wasn’t going to disappear. Addie hated me for it. I couldn’t help myself. I remembered the freedom I used to have—never complete, of course, but I remembered when I could ask our mother for a drink of water, for a kiss when we fell, for a hug.

<Let it go, Eva> Addie shouted whenever we fought. <Just let it go. Just go away.>

And for a long time, I believed that someday, I would.

We saw our first specialist at six. Specialists who were a lot pushier than the guidance counselor. Specialists who did their little tests, asked their little questions, and charged their not-so-little fees. By the time our younger brothers reached settling age, Addie and I had been through two therapists and four types of medication, all trying to do what nature should have already done: Get rid of the recessive soul.

Get rid of me.

Our parents were so relieved when my outbursts began disappearing, when the doctors came back with positive reports in their hands. They tried to keep it concealed, but we heard the sighed Finallys outside our door hours after they’d kissed us good night. For years, we’d been the thorn of the neighborhood, the dirty little secret that wasn’t so secret. The girls who just wouldn’t settle.

Nobody knew how in the middle of the night, Addie let me come out and walk around our bedroom with the last of my strength, touching the cold windowpanes and crying my own tears.

<I’m sorry> she’d whispered then. And I knew she really was, despite everything she’d said before. But that didn’t change anything.

I was terrified. I was eleven years old, and though I’d been told my entire short life that it was only natural for the recessive soul to fade away, I didn’t want to go. I wanted twenty thousand more sunrises, three thousand more hot summer days at the pool. I wanted to know what it was like to have a first kiss. The other recessives were lucky to have disappeared at four or five. They knew less.

Maybe that’s why things turned out the way they did. I wanted life too badly. I refused to let go. I didn’t completely fade away.

My motor controls vanished, yes, but I remained, trapped in our head. Watching, listening, but paralyzed.

Nobody but Addie and I knew, and Addie wasn’t about to tell. By this time, we knew what awaited kids who never settled, who became hybrids. Our head was filled with images of the institutions where they were squirreled away—never to return.

Eventually, the doctors gave us a clean bill of health. The guidance counselor bid us good-bye with a pleased little smile. Our parents were ecstatic. They packed everything up and moved us four hours away to a new state, a new neighborhood. One where no one knew who we were. Where we could be more than That Family With The Strange Little Girl.

I remember seeing our new home for the first time, looking over our little brother’s head and through his car window at the tiny, off-white house with the dark-shingled roof. Lyle cried at the sight of it, so old and shabby, the garden rampant with weeds. In the frenzy of our parents calming him down and unloading the moving truck and lugging in suitcases, Addie and I had been left alone for a moment—given a minute to just stand in the winter cold and breathe in the sharp air.

After so many years, things were finally the way they were supposed to be. Our parents could look other people in the eye again. Lyle could be around Addie in public again. We joined a seventh-grade class that didn’t know about all the years we’d spent huddled at our desk, wishing we could disappear.

They could be a normal family, with normal worries. They could be happy.

They.

They didn’t realize it wasn’t they at all. It was still us.

I was still there.

“Addie and Eva, Eva and Addie,” Mom used to sing when we were little, picking us up and swinging us through the air. “My little girls.”

Now when we helped make dinner, Dad only asked, “Addie, what would you like tonight?”

No one used my name anymore. It wasn’t Addie and Eva, Eva and Addie. It was just Addie, Addie, Addie.

One little girl, not two.