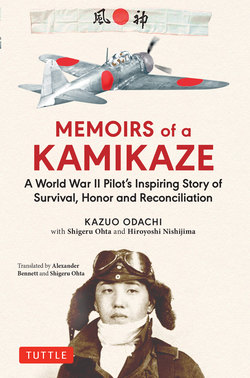

Читать книгу Memoirs of a Kamikaze - Kazuo Odachi - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеPROLOGUE

A little before noon on August 15, 1945, at an airbase on the north-east coast of Taiwan called Yilan, more than thirty Zero fighter planes carrying 500-kilogram bombs under their fuselages were preparing to take off. They were Kamikaze suicide planes and their mission was to attack hundreds of American ships anchoring off Okinawa. Succeed or fail in their mission, they would not be returning.

Clouds were high in the sky and it was very hot. The propellers sputtered into motion in a haze of smoky exhaust. The Zero piloted by sergeant Kazuo Odachi was in his squadron’s first team at the head of the runway, positioned to the left-rear of the section leader’s. The moment the planes began to move, an engine-starting car hurtled at full speed down the runway to block their path.

“Abort attack!” a mechanic shouted from the car. Somewhat startled by this sudden postponement, Odachi and the others disembarked their winged coffins and walked back to the command post. Before long, the somber voice of Japan’s emperor, Hirohito, crackled from the wireless speakers. It was difficult to hear, but the pilots got the gist of the imperial broadcast. Japan had accepted non-conditional surrender.

In the buildup to the mission, Odachi thought to himself “My time has surely come.” It was going to be the last of his eight attempted Kamikaze missions. But this time, once again, his life was miraculously spared. Fighting Grummans in aerial combat, strafed by American fighters when walking down a road, afflicted by malaria, making a narrow escape from Philippine mountains where hope had all but been lost.… He experienced all of this over the course of a year. For whatever reason, death passed him by and he was saved by the skin of his teeth more times than he cared to remember.

Student Draftees and Yokaren Trainees

In addition to footnotes, special columns such as this are included throughout the book to provide contextual information on Japanese history and some details related to Japan’s involvement in the Second World War. This is the first such column, and has been included at the beginning to explain why this story is so special.

Most people have heard of “Kamikaze,” but few, even in Japan, realize that there were essentially two categories of suicide attacker. This is not referring to the modes or units of suicide attack (planes, boats, human torpedoes, Navy Air Service, Army etc.), as there were several variations, but to the status of the men involved in aerial Kamikaze attacks.

Kamikaze suicide operations commenced around October of 1944. It was a desperate last resort for Japan with its military capacity having been crushed by a series of monumental defeats. Until the final stages of the war, young men studying at university in Japan had been exempted from compulsory military service. With the war situation worsening, however, a new policy to draft students was introduced in the Fall of 1943 to compensate for critical manpower shortages at the front.

Students were considered society’s elite, but thoughts of a bright and prosperous future were abruptly cut short for many when they were press ganged into service midway through their studies. A significant number received no more than a few dozen hours of flight training. Some did not even make 20 hours, so only had a rudimentary understanding of flying before being sent to their deaths in one-way suicide sorties.

They wrote long wills and letters to their loved ones. They mentioned the pain they felt about having to die so young, their philosophy of death, their love of family members, girlfriends and wives, and sometimes included private criticisms of the war and its leaders. Many such records were published in a well-known book titled Kike Wadatsumi no Koe (Listen to Voices from the Sea). Their moving letters left a deep impression on both Japanese and Western readers. Compared to this and similar books about the Kamikaze tragedy, however, readers will notice a different tone in this volume.

Kazuo Odachi and his comrades enlisted in the Yokaren in their mid-teens, fully aware that their chosen vocation was risky. The Yokaren was the much-lauded Japanese Naval Preparatory Flight Training Program for boys aged 15 to 17. Cadets were originally educated in a three-year preliminary course followed by one-year flight training, but this was considerably expedited by the time Odachi was admitted towards the end of the war.

Compared to student draftees, Yokaren graduates were highly skilled professional airmen. Their training was rigorous, and they were experienced in actual combat with the enemy before the Kamikaze strategy was devised. When they ‘volunteered’ for Kamikaze missions, their designated targets were enemy fleet ships, especially the biggest prize of them all aircraft carriers. To make the most of their expertise and machines, they had the option of returning to base if engine trouble occurred, the weather turned bad, or a suitable target was not located. Although each mission was embarked on as the last, this is how Odachi miraculously survived seven intended suicide sorties.

Odachi and the other battle-hardened airmen never wrote wills or sent letters back home before their final mission. They had long been mentally prepared to die in the course of duty. In this sense, therefore, there were two kinds of Kamikaze attackers: professional pilots, and amateur draftees. Odachi belonged to the former. That is not to say, however, that the sacrifice of one was greater than the other. Nevertheless, attitudes and expectations were different, and Odachi was one of only a small handful of his peers who came back from the war. That is why his story is unique.