Читать книгу Keiko's Ikebana - Keiko Kubo - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеIntroduction

The shapes and colors of flowers are naturally beautiful without even arranging them. A single flower in a bud vase, flowers in a garden, or a bunch of flowers thrown together in a vase all make enjoyable arrangements with little effort. So why learn ikebana? Though it takes more time to make ikebana than to simply throw flowers together in a vase, in making ikebana we receive more than just visual pleasure-we also receive the creative pleasure of crafting an arrangement through an interaction with nature. To interact directly with nature, or even to pause and appreciate nature, is something we seldom have the opportunity to do in our busy daily lives. Ikebana allows us to rediscover the beauty of nature and also to experience the personal fulfillment of realizing our own artistic vision.

Each of us possesses artistic creativity, but sometimes it's hidden from us unless we have the opportunity to be in a creative environment. Once the basic skills and techniques have been learned, we can convey our visual sensibility and creativity through ikebana.

About Ikebana

The word ikebana roughly means "bring life to the flowers." After the fresh flowers are cut from the soil (the death of the flowers), they are given new life when they are arranged in a container. Ikebana is also called kado, which means "the way of mastering flower arrangement" in Japanese. By "way;' we mean the way in which we master the art form. Sado, for instance, means "the way of mastering the tea ceremony," and shodo means "the way of mastering calligraphy."

Ikebana forms were originally composed of three main lines to symbolize the harmony between heaven, man, and earth. A miniature representation of the universe was created in the small container, with three lines of differing heights (tall, medium, and short), and the placement of these lines used to help structure a three-dimensional form.

Ikebana is an art form derived from a combination of several elements: nature, human creativity, and formal technique. Ikebana requires us to craft the arrangement carefully by observing nature, rather than focusing on speed and efficiency. In the process of making ikebana, we must pay close attention to the natural shapes, textures, and colors of the materials. It also generally employs a minimal use of materials. For this reason, the use of one line, one flower, or one piece of foliage has more meaning than the use of many.

There is a basic distinction between commercial and noncommercial arrangements. Although both types of arrangements ultimately serve as decoration and are meant to please the viewer, they each have a fundamentally different underlying purpose and function. The commercial floral arrangement requires speed because the arrangement must be made in a limited time and also requires someone to deliver it to the customer. It also has to match the customer's need (essentially, the desired materials at the desired cost). Ikebana, however, traditionally belongs to the noncommercial category of floral arrangement. It's created for a specific site rather than for delivery, and its purpose is to give enjoyment to the person making the arrangement as much as to serve any practical function.

Those who wish to learn ikebana usually take ikebana classes and spend three to five years learning the basic techniques, skills, and form. Those who have truly mastered ikebana, however, have continually refined their expertise over many years, if not over most of their lives.

The History of Ikebana

Ikebana is a traditional Japanese art form with a long history, although the influence of religious function, developments in Japanese architecture and cultural activities, and our changing lifestyles have also caused the art to evolve over time. At the beginning of its history, ikebana was practiced mainly by monks and the aristocracy. The Rokkakudo Temple in Kyoto is recognized as the original location where monks first began to practice ikebana.

The earliest practice associated with the origins of ikebana centered on the offering of flowers to Buddha at the temple. This type of floral arrangement came to Japan with the introduction of Buddhism to the country in the sixth century. The custom of offering flowers to Buddha is still seen in many Japanese homes that have a Buddhist altar. A few different types of flowers will be simply arranged in a tall vase and placed before the altar in the home. Often these arrangements are made by family members who don't have formal ikebana training. Although offering flowers to Buddha was the origin of Ikebana, it is around the fifteenth century that this practice first developed into a genuine art form.

The frequently prominent display of ikebana in the tokonoma, or alcove, found in the traditional Japanese home was important in elevating its status. The tokonoma, an element of the Shoin architectural style, is a recessed area used to display art objects and a central feature of the interior design. The room with the tokonoma was considered the most important place in the house and was used primarily to entertain distinguished guests and for special occasions. The tokonoma in the traditional Japanese home was adapted from the design seen in the homes of the aristocracy, but was simplified to accommodate the smaller dwelling size of the commoner.

It was after ikebana began to be displayed in the tokonoma in the homes of the aristocracy that its purpose changed from a religious function to the decoration of the home. The ikebana would be displayed alongside valuable artworks and a hanging scroll, and there had to be harmony among the items on display. Thus, the design of the ikebana displayed in the tokonoma became important. Just as the other artworks in the tokonoma would be replaced to reflect the changing seasons, the ikebana would also be changed to incorporate seasonal flowers. Even though it served a decorative function, the ikebana itself came to be appreciated as artwork.

In the sixteenth century a style called rikka (standing flowers) was introduced. This sophisticated style, created by Buddhist monks, utilized materials that were arranged in an asymmetrical form and placed upright in a tall bronze vase. The rikka style also depicted a miniature representation of the universe as symbolized by nature. Plants were used as symbols to represent the natural landscape.

Moribana-style arrangement

Another important Ikebana style originated around the same time that was strongly influenced by the tea ceremony as formally established in this period. Simple and natural ikebana arrangements were displayed in the tearoom where the ceremony was held. This style of ikebana is called chabana, meaning "tea flower;' and the composition uses relatively few materials. It is fairly natural looking and is typically displayed in a tall vase with a narrow mouth.

The development of chabana is closely associated with the nageire style, which literally means to "throw into:' It similarly utilizes an upright vase and is still practiced today as one of the main ikebana styles. Many of the step-by-step arrangements and techniques that appear in the following pages are based upon the nageire style.

By the late nineteenth century, Westernization had not only affected Japanese society but also its art and culture. The moribana style was created around this time and often used imported flowers, following the opening of the door to the West during the same period. Moribana, which means "stacked-up flowers," typically involves using a shallow container with a kenzan (also called the English needle-point holder or a frog) inside to support the materials. Unlike the nageire style of arrangement, the water's surface becomes one of the design elements in the moribana style because the container is so shallow and wide open.

Nageire-style arrangement

When the piled-up style of moribana was invented, it was an innovative departure from the standing (upright) style of ikebana used for so long. Moribana is likewise still practiced today as one of the main ikebana styles. Many of the step-by-step arrangements and techniques that follow are alternately based upon the moribana style.

In the twentieth century ikebana became more internationally known. The styles of arrangements were influenced by the modern culture, architectural styles, and art forms, as well as by changes to daily life.

Ikebana Today

Today, various styles and methods of ikebana are taught at different schools in Japan, many of which have their own approach to design. Some styles are quite classical, and others are contemporary to the point of being avant-garde. Just as the traditional Japanese architectural style had a strong influence on the development of ikebana, the contemporary architectural style is a strong influence on today's designs. We find a variety of ikebana styles well suited to the use of space in contemporary architecture.

Natural-looking ikebana was customarily thought appropriate for use with the traditional Japanese architecture constructed mainly of wood and paper. However, both container choices and ikebana styles have changed to match contemporary architecture that is often constructed primarily out of industrial materials such as steel, glass, and concrete. Modern-looking glass or metal containers and sharp, geometric lines generally match favorably with this type of space. However, I think that a blending of contemporary and classic designs can lead to interesting results. For instance, a modern-looking container can go quite well with a natural-looking arrangement, depending on how it's created and the site of display.

The changing lifestyles and developments in architecture have also influenced the placement of ikebana in the home. As mentioned previously, ikebana is traditionally placed in a tokonoma. In the modern era, Japanese people live in one of three primary types of home: traditional Japanese style, Western style, or an in-between type that includes elements of both Japanese and Western design. Ikebana styles developed that likewise incorporated both Japanese and Western design principles, and today, in homes without the traditional tokonoma, the style of ikebana has been altered for placement in an entrance hall, living room, or elsewhere.

In the traditional tokonoma, the ikebana is arranged facing towards the viewer. Other artworks (such as scrolls or ceramics) are usually displayed alongside the ikebana, meaning that the arrangement's size is limited, and achieving harmony between the ikebana and other artworks becomes important.

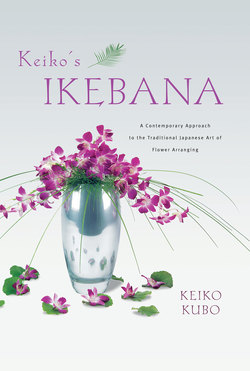

This is an example of my freestyle approach to ikebana. My emphasis on lines in the design, minimal use of materials, and simplicity are related to the ikebana aesthetic. The freestyle ikebana form is an individual creative expression using natural materials as the medium.

For ikebana placed in an entrance hall, on a living-room table, or in another typical display site in Western homes, the arrangement's size should vary depending upon the size of the space and the anticipated perspective of the viewer. For example, for display in an entrance hall, where space is limited, a small arrangement can be made using fewer materials. Similarly, if the ikebana will be displayed on a table, it can be designed using a shallow container and shorter materials so that persons seated around the table can better view the arrangement.

Arrangement sizes can vary widely depending on the display site, and range from a small size for the home to a larger size for the temple or a much larger size often seen as decoration for a special occasion, such as a ceremony or party. The function of ikebana also varies, from its use in ceremonies to its display in a private or commercial space or its presentation in a public space such as at an ikebana exhibition.

Keiko's Approach

Just as new innovations in ikebana style have arisen throughout this art form's history, a contemporary style of ikebana is developing that is part of the twenty-first century. Today, we find flower arrangements that are a blend of ikebana and Western floral art. East meets West in many ways in our modern society; they have influenced one another, and so we find a fusion of the two cultures-in art, music, architecture, cooking, and fashion-in our everyday lives. In this type of cultural environment, I am very interested in making ikebana that doesn't fit into one rigid category or style.

The method that I use is simple and is based on a freestyle approach that utilizes basic ikebana techniques, but that is also influenced by Western-style floral design and my background in fine arts. It can be made by anyone interested in creating a three-dimensional sculptural form using natural materials as a medium of expression. Since each arrangement is a unique personal statement, the results will vary among individuals-even if they use the same materials.

The materials that I use emphasize a minimalist approach (minimal quantities of flowers, branches, and foliage) that is part of the ikebana aesthetic. My style of ikebana is uncomplicated, but the resulting arrangement conveys a strong sense of identity in the space where it's displayed.

Ikebana offers the reward of working closely with nature, which leads me to contemplate the natural cycle in which flowers, trees, and all living things coexist (nature's cycle of death and renewal with the passage of time) . I like to create ikebana to express my self-identity, to present the beauty of nature, and most importantly to complement the times in which we live and the spaces we live in. Working with flowers gives me a sense of connection with the natural world and also a feeling of comfort and healing that comes from the power of nature.

I truly wish to share the exhilaration of creating freestyle ikebana and to inspire others to try and create their own ikebana designs. The following material contains some basic techniques, tips, and other information to help you begin crafting your own arrangements. Each step-by-step arrangement was created using a different primary technique and design style. I hope this provides enough ideas and information to get you started making ikebana!