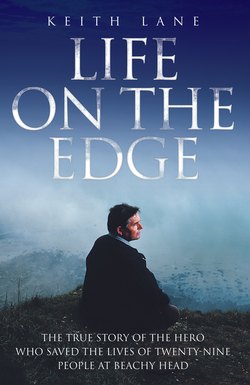

Читать книгу Life on the Edge - The true story of the hero who saved the lives of twenty-nine people at Beachy Head - Keith Lane - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ROAD TO RECOVERY, ROAD TO RUIN

ОглавлениеWith depression and alcoholism, a person must recognise and accept they have a problem before they can begin to deal with it. The same goes for any illness, of course. Recognition is the first big step to recovery. Maggie was suffering from both depression and dependency on alcohol and as we lay in bed in the early hours, I brought the subject up with her.

‘Sweetheart,’ I began, ‘I love you more than anything and that’s why I’m going to say what I’m about to say. I think you have a problem with alcohol. I think you need help. You need to see someone about your drinking – a counsellor, perhaps.’

Maggie nodded. She seemed to agree. For the first time I was getting through to her and I felt a massive sense of relief. Maggie agreed to go to Alcoholics Anonymous and I was quietly over the moon.

The meetings helped her; I encouraged her and Maggie went teetotal. It was amazing how quickly things began to get back to normal. It was as if the real Maggie had finally returned from a long holiday, and as each day went by I could see her improving. The difference was incredible and obvious. Just as my family had thanked Maggie for coming into my life and bringing me back to my old self, Maggie’s family thanked me for encouraging her to lay off the booze. They cared for her deeply and had been as worried as I was about her downward spiral. We were all so happy to see her nearly back once more to being the bubbly woman we loved. She was still on anti-depressants, but now she was off the drink they were working properly – it’s well known that alcohol will interfere with (and render useless) most psychoactive drugs.

To my delight, she decided she was ready to go back to work, so began temping locally while she looked for a full-time job. It was wonderful to see her flinging herself at life again instead of sitting at home. But there was a problem. For one reason or another, things kept going wrong at work. A job would end, and she’d have difficulty finding another. Eventually she’d find one but then get knocked back again after a few weeks. With the memory of the job she had loved in her mind, Maggie found it hard to find anything to match it and this started to get her down. After several kicks in the teeth, her moods began to dip again. She hadn’t had a drink for three months, but towards the end of that period she must have started to lose faith again. And that’s when she turned back to the bottle.

When Maggie agreed to stop drinking, I felt she’d taken the first big step to becoming well again. Indeed by stopping drinking she had taken a huge step. But what I didn’t consider at the time was exactly why. Looking back, I can see that she was doing it for me, because she loved me, because she could see the damage that it was doing to our relationship. And that’s the point – she was doing it for me, but not for herself. Maggie was still in the grip of alcohol even when she wasn’t drinking. Even though she was sober, she still wanted to be drinking. Giving up required strength – and boy, she could be strong when she wanted to – but when a person has deep-rooted problems, those problems often win out. Maggie’s resolve went because her problems overwhelmed her again.

I began to find booze hidden away again and it was a real blow. I felt we’d come so far. It wasn’t that I was sad for myself. I was sad for my wife and I didn’t know what to do. This time around, Maggie’s drinking was worse than before. It became more secretive and now I’d even find small bottles tucked away at the bottom of her handbag. Maggie began to drink throughout the day and would even fill up water bottles with vodka so that she could drink in public and at work without raising any eyebrows. It was such a sad time, and there was very little I could do to stop her. It was as if she’d resigned herself to being a drinker. Before long she was physically dependent on alcohol and would drink any time, morning noon and night. If Maggie didn’t have access to liquor she would be in a real state – mentally agitated and physically shaky – yet even though it was obvious how dependent she was, she would still frequently deny that she was drinking.

I remember coming home from golf one day and finding what looked like a glass of orange juice on the bedside table. I picked it up and could smell vodka in it. When I asked her about it she was adamant that it was just orange. There was no point in getting into an argument, so I left it. Watching a person in denial is a frustrating thing and I used to boil up inside whenever Maggie lied in such a way, but I would always try and count to ten and walk away – labouring the point would have been destructive and a waste of time. When someone is so deeply in denial they have got to a point where they really believe what they are saying. It’s hard to comprehend, but this is what happened to Maggie.

On occasions, it was really hard to control my anger and frustration. There were a number of times when Maggie would lock herself in the bathroom for no reason other than to be able to drink. I’d be around the house and eventually realise where she was before walking up the stairs to try and coax her out gently. But most of the time talking was no use – Maggie either didn’t want to come out or she was too drunk to respond to me coherently. In the end, I’d have to resort to threatening to kick the door down – sometimes I even began to kick it pretty hard, though I never actually kicked it in – and it was only then that she would open up, fall into my arms and cry. I’d try and be positive, telling her that we could get through this, that things could be OK again, but things only went from bad to worse.

I’d find Maggie really out of it, being sick down the toilet and over herself, and the process of cleaning everything up and trying to straighten her out broke my heart. All the time this was going on I would think back to the woman I once knew and wonder how things had got so bad. I sometimes asked myself whether it was all my fault. Looking back, I think I can say it wasn’t, for I would soon discover that there were more contributing factors to Maggie’s depression than her life as it stood – she had a dark past – and I would soon be given a glimpse into it. But something truly awful was to happen first.

My wife would try to kill herself.

I came home from a busy day at work. Maggie was nowhere to be seen downstairs – as was often the case these days – so I walked upstairs to find her. My first reaction to what I found was complete shock. For a few moments I simply froze. Maggie was in the bedroom, sprawled on the bed, passed out with her head tilted back and her eyes rolled back, an empty bottle by her side, along with an empty packet of antidepressants. The realisation that she had overdosed hit me and after a couple of seconds I leaped into action, rushed down the stairs and dialled 999. The voice at the end of the line told me to leave the front door open, go back upstairs and try to wake Maggie up. Once back at her side I shook her, kissed her and did everything I could to try and bring her back to consciousness. Maggie came round a tiny bit and began murmuring, but it was hard to keep her awake – her eyes were rolling and her body was completely limp. All I could do was hold her and call her name in an effort to keep her with me.

I can barely describe the feeling of being on that bed by Maggie’s side. When I first found her, the adrenaline kicked in and I simply went into a practical mode. But I had time to think once I had called the ambulance and managed to bring her round a little. And that’s when the fear kicked in. The reality of the situation hit me like a hammer and I began to tremble and sweat with sheer panic. The woman I loved so dearly was lying in my arms and close to death yet there was nothing I could do but wait. I felt so lonely and useless, paralysed with terror that my Maggie was about to die.

‘Don’t worry, she’s going to be OK,’ the paramedics reassured me after several minutes of working on her. Those words were like a ten tonne weight being lifted from my shoulders. They strapped an oxygen mask to her face, and whisked her off to A & E. I followed in the car, and after hours of vomiting and rest Maggie eventually came round fully.

A psychiatrist assessed her, told me that Maggie needed help and arranged for her to see a counsellor once a week. Maggie agreed to the arrangement, but she was more concerned with the fact that she’d put me through the mill again. She was full of apologies and I know she really was sorry. To an outsider, it may appear as if Maggie’s behaviour was purely selfish, but I don’t see it that way at all. I saw that what she was going through was part of an illness. Sure, that illness meant I had to go through a lot of shit with her, but I went through it because I loved her so much and believed we could get through it.

It used to make me really mad when people said how awful it was that Maggie was putting me through so much. ‘Don’t you dare judge Maggie, nor me,’ I’d reply. ‘If you had cancer and were being sick all over the place, would you like to have your better half look after you? Of course you would, so don’t slam her or me just because her illness has a stigma attached to it.’

I don’t care how much Maggie made my life difficult – I won’t hear a bad word said about her. I chose to stay with her because I loved her and that’s it. It wasn’t me that was a victim, it was her. Seeing her in that hospital made it very obvious who was suffering the most and when she said sorry and that she would try to get better I could tell that she meant it. Yet, looking back, I can see that she was so trapped in her illness that she only wanted to get better for my sake. Once again it was me that was putting the words in her mouth.

I asked her if there was anything I could do to help her and she told me that I couldn’t do anything more than I was already doing. I remember telling her that she needed to give up not for me, but for her. She would nod in response and say ‘Of course I’ll stop’, but not once did she say that she needed to give up for her sake, for our sake. I think the points at which Maggie said she would stop are comparable to the situation of a husband who beats his wife but insists he will stop – at the time he says it, when all the remorse and regret is there, he truly believes that he won’t hit her again. Time passes, however, and the original unresolved problem overwhelms the man, whatever his good intentions, and he does it again.

We left the hospital and the cycle started all over again. For a while Maggie stopped, but then she lapsed once more. This went on and on, and every time she lapsed she fell further and crashed harder than before. She began to disappear from the house and stay out for hours and hours without letting me know where she was. Because of her history with booze, I found this hard to bear. The worry her disappearances caused me was overwhelming. On countless occasions I’d let the clock tick until I could bear it no longer – your imagination goes wild when someone you love goes missing, especially when they have a problem. I used to worry that she was in a bar somewhere, smashed out of her head, and that someone might take advantage of her – rape her, murder her even. The paranoia would set in and a number of times I had to call the police to help me find her.

I remember one night when I’d been waiting for Maggie for hours and hours. Eventually, at around 11.30 pm, she called. Her speech was so slurred that I could barely understand what she was saying, but I managed to glean that she had booked herself into a hotel. I drove over and picked her up – literally – before driving home. When we pulled up outside the house, I opened the car door and went to support her. But I misjudged it a little and she collapsed in a heap on the kerb.

As I carried her towards the house I could see a few of the neighbours’ curtains twitching and I knew we were being watched. It sounds awful, but when you have the one you love in your arms, and she’s completely drunk again, and people are watching, it is embarrassing. I felt bad for Maggie’s indignity, and I felt bad for myself – I suppose it was only natural. I propped Maggie up against the wall while I opened the door, then carried her inside. I struggled up the stairs, undressed her and put her into bed.

Then I wept.

It was one of the first times I’d really cried about it all. I’d been holding so much in and had been hoping that things would work out for so long, but that night I just began to fall apart a little. I sat on the edge of the bed, stroking Maggie’s head and crying my eyes out. I couldn’t believe this was happening. I didn’t know which way to turn any more. I’m doing all I can here, I thought to myself. I’ve got her counselling, I’ve got her to AA and I’m giving her all the support I can, so why is she not responding? What am I doing so wrong, for God’s sake?

I knew that there would be the usual apology in the morning. There was, but with a heartbreaking twist.

‘I’ve really hurt you this time, haven’t I?’ said Maggie, her face filled with remorse and sadness.

‘Yes,’ I said. I couldn’t lie to her. The situation was tearing me up inside.

‘Well, OK, go on then,’ she said meekly. I had no idea what she was talking about.

‘What do you mean, “Go on then”?’ I replied, confused.

‘Go on,’ she replied, ‘hit me.’

I was dumbstruck. ‘Why would I hit you?’ I said incredulously. I could hardly believe the words had come from my wife’s mouth.

‘Because that’s what men do. It’s what I deserve. I’ve always been hit. I’ve always been beaten.’

To realise that Maggie felt this way about herself, to know that she thought I wanted to hit her, broke my heart. I took her hands in mine and looked right into her eyes.

‘I would never touch a hair on your head apart from to care for you,’ I told her firmly.

‘Hit me,’ she said again, ‘just give me a good hiding and it will all be forgotten.’

‘No,’ I protested, ‘I won’t hit you, and I’ll never hit you as long as I live. If I ever went for you it would be over. I’d walk because we’d be finished.’

‘Well, what can I do to make it up to you?’ she asked.

‘All you can do for me is get better, darling,’ I said as tears began to stream from my eyes. ‘I love you so deeply that it’s all I want.’

It was one of the most depressing conversations I’ve ever had, but it offered me a little more insight into the causes of Maggie’s depression. In the past, long before we met, she had taken several beatings. I began to think that it was her past that was haunting her and I wondered if addressing whatever demons lurked there might help her.

It was when Maggie attempted to slit her wrists that I decided to try and get to the bottom of her past, and that’s because I saw this incident as little more than a cry for help – I didn’t believe that Maggie really wanted to die, but I felt she was calling out for someone to rescue her. The attempt itself was almost half-hearted, if that doesn’t sound too unsympathetic. Rather than a knife, Maggie used a razor blade and didn’t take the cover off. Perhaps it was because she was too drunk – who knows? – but she only had a few scratches down her arms. I took her cry for help as an opportunity to play the psychiatrist and try to understand her past in order to hopefully help the present. Maybe, I thought, just maybe, if Maggie can exorcize her demons with me, if she can face up to whatever is haunting her, then she’ll be happy in herself, get her confidence back and be able to face the problem of the demon drink. Perhaps it was wishful thinking, but I was desperate to explore any avenue that might lead to Maggie getting well.

So I started to ask about her past and, indeed, she’d had her fair share of trouble. She told me that her problems had started from an early age. Her mother died when Maggie was only three and her father destroyed all the photos of her, so Maggie never got to find out what she looked like. Her dad found someone else, who became Maggie’s stepmum, and there was a lot of friction between Maggie and her. Put simply, Maggie received some pretty awful treatment at her stepmum’s hands – she told me that she was locked in cupboards as a punishment for minor things, that she was beaten regularly and that she had vivid memories of lying on the floor, crying, and her stepmother simply walking over her. To make matters worse, her stepmother would tell her father that Maggie had been bad when she hadn’t, which resulted in Maggie being banished to her room – punished for no good reason. This was very painful for her, because until her stepmum came along Maggie had received a huge amount of love and affection from her father. She had fond memories of sitting on his lap listening to nursery rhymes, and of feeling warm and secure when he read bedtime stories to her. Yet once Maggie’s stepmum arrived on the scene and began telling fibs about her, the affection dropped away and he began to lock her in her room. In Maggie’s mind, within a year of losing her mum she had lost her dad too.

Anyone with negative early experiences is likely to have problems with self-esteem and depression as they get older. To feel rejected by your own family sets you up for a life of feeling bad about yourself, of feeling you don’t deserve affection, and makes you far more likely to get into bad relationships where it is somehow ‘the norm’ to be treated badly. I think Maggie’s past partly explains why she ended up going for men who treated her unkindly – it was a weird way of replicating what she know best and of letting history repeat itself. When you’re a kid and the version of ‘affection’ you get is mucked up, you’re going to take that on with you in life.

Some people can deal with the problems they faced in childhood – whether it be through therapy, talking to friends, or just thinking long and hard – but I don’t think Maggie ever came to terms with the traumas of her past. What’s more, I know I never got her whole story from her – I can never shake from my mind something she said to me a number of times when we talked about her past. ‘You’ll never know the whole truth,’ she’d say through her tears with deadly seriousness, but no matter how much I probed she would not elaborate on certain areas. Quite obviously, things had happened to Maggie that were just too painful for her to talk about.

I know there are two sides to every story and I was always conscious of this when listening to Maggie’s point of view about her past. It’s often natural for a person to exaggerate and sometimes I asked myself whether or not she was bending the truth in some way. My gut feeling is that she wasn’t because I could see so clearly how depressed she was and how much her past haunted her. I may be wrong, but I don’t think Maggie would have ended up with such bad depression, or such an addictive personality, were it not for her troubled past.

Talking about her history may have helped Maggie get things off her chest, and it gave me more insight into what lay behind her drinking and depression, but it didn’t help with the problems of the present. Maggie’s periods of sobriety shortened to the point that I was never sure if she was actually off the booze. I’d find it in any number of places around the house – at the back of cupboards, hidden in the linings of cushions and pillows – and Maggie knew I was looking too. ‘Here comes old supersleuth,’ she would joke sarcastically. ‘Where are you going to look tonight, then?’

Trying to catch Maggie out all the time was probably not helpful, and it certainly didn’t stop her from drinking, but I was in a position where I really didn’t know what else to do. I’d tried everything to get her to stop, so at the very least I wanted to know what was going on and whether she was drinking or not. More often than not, she was.

Gradually, Maggie’s disappearances became more frequent and she began to go missing overnight; it was agony not knowing where my wife was. She also took another couple of antidepressant overdoses, one of which caused her to have a fit that frightened the life out of me. I was at my wits’ end, but I never thought about giving up hope.

During one spell in hospital, a psychiatrist asked Maggie if she realised how much her behaviour was damaging not just her, but me too. To this day I’m convinced that she took this on board and I think part of the reason Maggie ended up taking her life was that she didn’t want to put me through such misery any more. She felt she would never get better and she didn’t want to drag me along with her any longer.

Life was becoming very hard, and one day there came a moment where I thought the unthinkable; even now I’m ashamed to admit to a feeling that flashed through my mind one night. I had just returned home from a party. I’d had my doubts about going, because by that stage I didn’t want to leave Maggie alone, but she had persuaded me that that she would be OK – all she wanted to do was sleep, she said. She wanted me to go and enjoy my evening. I went to the party, but I was so worried about what she might do in my absence that I only stayed for an hour before returning home. It turned out that I was right to be worried.

I found Maggie had overdosed again – the bottle and the empty sachet of pills were by the bed and on the bed itself was Maggie. She was absolutely out of it. Oh God, I thought, I can’t take this any more, and for a brief moment I thought how it would be the easiest thing in the world to simply turn on my heel, walk out of the house and make out that I hadn’t come home at all.

That’s right: I thought about leaving my wife to die.

Needless to say, I didn’t turn on my heel, and I hated myself for having even thought such a thing. But think it I did. Getting to the point where I could contemplate such a terrible thing made me realise just what an impossible situation Maggie and I were trapped in. Life had turned from a dream into a nightmare. Maggie was lost and so was I.