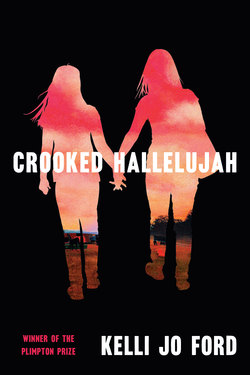

Читать книгу Crooked Hallelujah - Kelli Jo Ford - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеBook of the Generations

1.

When Lula stepped into the yard, the stray cat Justine held took off so fast it scratched her and sent the porch swing sideways. Justine had been feeding the stray, hoping to find its litter of kittens in spite of her mother’s disdain for extra mouths or creatures prone to parasites. She tried to smooth cat hair from her lap. She’d wanted everything to be perfect when she told her mom that she’d tracked down her father in Texas and used the neighbor’s phone to call him.

“That thing’s going to give you worms.” Lula dropped her purse onto the porch. She hadn’t been able to catch a ride from work. With a deep sigh, she untucked her blouse and undid the long green polyester skirt she’d started sewing as soon as she’d seen the HELP WANTED sign at the insurance office. She was a secretary now, and as she liked to tell Justine, people called her Mrs. and complimented her handwriting.

“I’ll wash up,” Justine said. She’d already decided today wasn’t the day. Like yesterday. And the day before that.

“At least let me say hi.” Lula kicked off dusty pumps and let her weight drop into the swing beside Justine. The swing skittered haywire as Lula pulled bobby pins from her bun, scratching her scalp. Her long salt-and-pepper braid fell past her shoulder and curled under her breast. “Bless us, Lord,” she said, the words nearly a song. She closed her eyes, and as she whispered an impromptu prayer, she touched the end of her braid to the mole on her lip that she still called her beauty mark.

As a girl, Justine had pored over the pictures from Lula’s time at Chilocco Indian School, trying to see her mother in the stone-cold fox who stared out from the old photographs. Lula’s clothes hung loosely, even more faded than the other girls’ in the pictures, but something about her gaze—framed by short black curls, of all things—made it seem as if she were the only one in the photo. If Marilyn Monroe had come of age in an Indian boarding school and had fierce brown eyes instead of scared blue ones, that would have been young Lula. Justine kept the old pictures in a box hidden in the top of the closet where she kept her Rolling Stones and a mood ring, other forbidden things. She hadn’t thought of the pictures in ages, but she did so now as she watched her mom in prayer.

Lula whispered amen, caught Justine staring at her.

“Granny’s out gathering wild onions with Aunt Celia,” Justine said quickly.

“Late in the year for it,” Lula said. She unrolled her nylon stockings and wiggled her toes in the air. In the way of Cherokee women, Lula could still make you feel that she held down the Earth around her one moment and then seem almost like a girl the next. “Did you do your homework?”

“I swept and did the rugs too.”

“My Teeny,” Lula said, calling her the nickname that had stuck when Justine’s middle sister, Josie, hadn’t been able to say her name. Together they pushed the swing back and let it fall forward.

Justine closed her eyes. In the cool air that had come with the night’s rain, her mother’s warmth felt nice, which made the words she’d been practicing feel all the worse.

“Evenings like this make me wonder how a body would want to set their bones anywhere other than these hills,” Lula said.

Justine opened her eyes. The two-bedroom house they rented with her granny sat on the edge of Beulah Springs, the outer walls almost as much tar paper as asphalt shingle. She had her own room now that her sisters, Dee and Josie, had married themselves out of state, but her mother and Granny still split a room barely big enough for one. Hand-sewn curtains strung on a clothesline separated their beds. The low green hills beyond the train tracks seemed like folds in a crumpled blanket after Dee sent her pictures of Tennessee mountains. Justine had a good idea why a body might light out for other hills, other lands.

“I talked to Daddy.” Her nerves blurted it out for her.

Lula put her feet down to stop the swing. Justine couldn’t read her mother’s face, but she wished she could put the words back in her mouth, swallow them for good.

Justine’s father had dropped the family off for a Saturday night service at Beulah Springs Holiness Church almost seven years back. As far as anyone could tell, he’d then been swallowed up by the Oklahoma sky. He’d never sent an ounce of child support or a forwarding address, never even called.

Lula held herself together with a religion so stifling and frightening that Justine, the youngest and always the most bullheaded, never knew if she was fighting against her mother or God himself, or if there was even a difference. Still, her father was a betrayal of the knife-in-the-heart variety—something far beyond all their fighting—and here he was on a cool spring evening, right between them.

“He’s in Texas. Near Fort Worth,” Justine said. She bit her lip. “He asked me to go to Six Flags with him. Just for the weekend. He has a little boy now, I guess.”

She almost hoped Lula would hit her, but Lula stared into the hills. It wasn’t clear she had heard, so Justine’s mouth kept moving.

“Six Flags is an amusement park. With roller coasters. I know you might think it’s too worldly, but I can wear a long skirt on the rides and all. It’s sort of like a big old playground!” Justine forced a smile. She pushed a strand of hair back into her bun and waited. “I’m sorry, Mama.”

Lula remained quiet, focused on the horizon.

“I guess I pestered Mr. Bean at the plant so much he helped put me in touch.” She didn’t say that she’d gotten the information from her dad’s old foreman almost two years ago and then been so ashamed that she tore the paper into bits she spread over Little Locust Creek. A few weeks back, her treacherous mind had begun to play the numbers across her thoughts, a musical sequence that interrupted her over dinner or during tests.

“I’m real excited about Six Flags,” she said, and despite everything, she realized it was true.

“I’ll talk to Pastor about it,” Lula said, finally. She pushed herself out of the swing and walked inside.

At first Justine was surprised at how well it had gone. Then she saw Lula’s purse kicked over on the porch, her comb and Bible in a puff of cat hair. Justine scrambled to retrieve them and ran her hand over the textured leather cover of the heavy book.

She pushed past the screen door and went to her mother’s room, where she could hear Lula already in prayer. One of Lula’s drawings of a Plains Indian’s teepee was tacked to the closed door. Justine knew that on the other side of the teepee, her mother knelt, as she did in church. Instead of a wooden pew or an altar, Lula’s face was buried in her twin bed, if she had made it that far. Justine ran her finger over the smooth indentations of her mother’s ink. She wanted to take Lula the purse and Bible, decided that if Lula stopped praying, she would make herself push through the door. She would go into the small, dark room, where maybe she would lay her head on her mother’s shoulder. If she did, Justine knew that her mouth would open back up. Instead of telling Lula about Six Flags and a new half brother, Justine would tell her about what Russell Gibson did to her.

She wouldn’t be able to omit the details of the night she’d snuck out and met him down their dirt road, how he looked back over his shoulder then let her steer the car while he pushed from the open driver-side door, only cranking the engine once they were well out of Lula’s earshot. How her stomach flip-flopped over the way he had looked at her as he drove, shaking his head, saying, “Fif-teen,” and how her insides had frozen when she noticed a blanket folded neatly in the back seat. She would say how very sorry she was that she had pretended to be asleep that night when Lula stuck her head into the dark room and said, “Good night, my Teeny. Love you.” She would tell her how she’d thought his abrupt movements must have been what first dates were made of. She would tell Lula that she said no quietly at first.

But Lula’s prayer rose and dipped into a moan. Then great, body-shaking sobs vibrated through the door into Justine’s hand, along her arm, and into her chest. She dropped the purse and Bible on the kitchen table and locked herself in the bathroom.

“Shit. Shit. Shit,” she muttered. Feeling as if her bones were shaking, she took a can of Aqua Net, covered her eyes, and sprayed it all around her head. She waved hairspray from the air and then scrubbed her face red with scalding water. Her father’s blue eyes reflected back at her, not Lula’s brown eyes or eyes that seemed her own. Mostly she didn’t think about him anymore. She didn’t think she wanted to see him, but what was done was done. She decided then that she would go to Six Flags with her father and never think of Russell Gibson again. It was as if her young heart could only hold the two emotions: one, a guilt so deep for betraying her mother that it left her feeling like a human rattle, empty save for a few disconnected bones; and two, a joy so sudden and surprising at the thought of riding Big Bend, the fastest roller coaster in the world, that she felt she might pass out.

2.

“We’d love to have you, babe,” her father had said. “We’ll go to Six Flags. It’ll be a blast.” Through the crackly long-distance line, his baritone sounded familiar but busy, his words fireflies that flitted between them without illuminating a thing. She cradled the telephone on her shoulder and counted France, Spain, Mexico, Confederacy, United States on her fingers, trying to think of the sixth flag. “Roller coasters big as mountains,” he’d said. “Hold on.” She heard muffled talking, then he came back. “Justine, is everything okay?”

“Just dandy,” she said, and he was off again, filling the distance between them with empty words. It was a presumptuous question after all these years: Is everything okay? Where to begin? She knew he’d meant: Why now? Just like she knew that if he’d really wanted her to visit, she wouldn’t have had to go to such lengths to find him. She should have called her oldest sister, who was spending the summer on the Holiness Camp Meeting circuit with her new preacher husband.

Six Flags, like the basketball team she’d wanted to join last year, was “of the world.” Justine could hear Lula already: “The world passeth away, and the lust thereof: but he that doeth the will of God abideth for ever.” Justine was only fifteen, but she held no illusions—nor intentions—of abiding forever. Maybe Six Flags would be less hurtful than the truth that she needed to get away from here. And that her father was the there.

She had imagined the night for weeks after Russell Gibson had first spoken to her on her class trip to Sequoyah’s Cabin. When she’d seen him working on a water leak outside the stone house covering the cabin that day, she recognized him. Her cousin John Joseph played music with him. She knew he was twentysomething, Choctaw, already back from the war. He had his shirt off and a rolled red bandana holding walnut-colored hair out of his eyes. When he saw her looking, he grinned and dropped his shovel for a pick mattock that he buried in the red earth.

She slipped away and let him write a phone number on her wrist, not telling him they didn’t have a phone. She liked that he wasn’t much taller than her but had wisps of a mustache. She thought the homemade outline of the Hulk tattooed on his forearm was cool and pictured them going to a drive-in movie in Fort Smith. Or maybe he would lean on the hood of his car and sing her a song: sinful, surely, but nothing she couldn’t pray her way out of. Every bit of that had been the work of a girl’s imagination, nothing else. They hadn’t gone to a movie, and he didn’t even bring a guitar.

She had her first moment of regret when she looked back at their little house, porch light glowing on the hill, but then he let her start the car. She revved the engine and laughed. Freedom had been waiting just on the other side of her bedroom window! He used his thigh to push her to the middle of the seat and took the wheel. He passed her his cigarette and rubbed her leg when he wasn’t shifting gears. Time and place swirled together as he turned onto a two-track road that disappeared into Little Locust Creek. He pushed the emergency brake, and before he cut the lights, she could see where the two-track, broken by the black water, picked back up on the other side of the creek.

She thought she should have fought him, thought maybe she’d unknowingly agreed to what happened. Her mind kept mixing up the jumble of memories from that night, but it returned again and again to Proverbs 5, a favorite of church deacons. She suspected she caused the whole thing.

She told herself that if she could forget the terrible night ever happened, it would be so. She didn’t sleep for days. Numbers replaced her thoughts. She found her father. When her body grew too tired to keep up her mind’s tormented vigil, she dreamed of roller coasters.

3.

Lula came red-eyed out of the bedroom. Her voice nearly a whisper, she said that if Justine wanted to see her father, it was her choice. “It seems you’re old enough, Justine, that your salvation is your own burden.” Then, her voice sharper: “And if you want to ride a roller coaster in your first act as a spiritual adult, so be it.” All Justine had to do was make it out of Wednesday night service.

People in town called them Holy Rollers, but the congregation of Beulah Springs Holiness Church referred to themselves as the Saints, the hardy few called to travel Isaiah’s Holiness Highway. They set themselves apart from the world with their Spirit-filled meetings, faith healing, prophetic visions, and modest dress. Though even wedding rings were forbidden as outward adornment, they believed once married, always married: Lula’s solitude was a sentence of belief and circumstance. They believed Stomp Dances were of the devil, that God healed what was meant to be healed, and children obeyed. Justine learned early that life was made up of occasional threads of joy woven through a tapestry of unceasing trials and tribulations. Life was spiritual warfare, and Six Flags would be no exception.

Justine sat where she always sat, in the back pew with her cousin John Joseph. His father was Lula’s brother, Justine’s Uncle Thorpe, but first and foremost he was their pastor. John Joseph’s black hair was stuck behind one ear in a greasy clump. He had his father’s square jaw and his mom’s gray eyes, which made him a hit with girls in town, girls who didn’t go to a Holiness church or wear slicked-back buns and skirts down to their ankles. Like Justine, he was old enough to be an adult in the eyes of God and their church, and like Justine he hadn’t prayed through, no matter what terrors his soul faced in this world and after. “Jesus wept” had been their favorite Bible verse for as long as she could remember. She always thought it was because it was the shortest and easiest to recite on demand, but lately she’d found herself wondering why the words were so sudden and set apart.

Justine’s eyes welled up, so she kept them on her lap while Uncle Thorpe finished his sermon with a story about a teenager who had died in a car wreck on his way home from a concert. The teenager had been raised Holiness and knew better. Uncle Thorpe walked around the simple wooden pulpit, rested an elbow on it, and looked at Justine. He wiped his eyes with his handkerchief. One brylcreemed strand of hair had fallen onto his forehead, like some kind of Native Superman. Justine imagined herself melting to nothing on the floor and sliding away.

Up there in front of the whole ragtag congregation filled mostly with poor whites, mixed-bloods—nearly half of whom were Uncle Thorpe’s kids—and a few full-bloods like her granny, Uncle Thorpe spoke to her: “The pleasures of this world may seem great. They are supposed to, for if we are not tested, like Jesus in the wilderness,” he shouted, raising his voice until it cracked, “how can we find our salvation?” Tears fell down his face. “Justine, God’s talking to my heart. You could die on that roller coaster.”

Not just a roller coaster, she thought. Big Bend.

The Saints began to whisper to God to intercede in her sinful plans. Uncle Thorpe took a long time wiping his eyes. He blew his nose and opened his arms wide, palms to the sky, and said, “Saints, we’re going to start up altar call.” From a raised platform behind the pulpit, the four-piece band lurched into “Consider the Lilies.”

“If you hear the Lord talking to you today,” Uncle Thorpe shouted over the music, “even if the voice is small, Saints”—his own voice grew quiet—“maybe it’s doubt nagging from the back of your mind. Maybe it’s sorrow or quiet longing tucked away in your heart. Maybe it’s fear for your children. Maybe it’s been too long since you’ve prayed through. Or maybe you never have.” He held his eyes on John Joseph, who never stopped digging dirt from his fingernails with his pocketknife. Then Uncle Thorpe turned his eyes back to Justine. “Come, children. Jesus is waiting. The only way to him is to bow your head and ask him into your heart. It doesn’t matter how you got here or what you’ve done. You will know a new day, children. I love you, but only God can turn this car around.”

Lula moved toward the altar first, and then other Saints streamed to the front. Some knelt before the altar in prayer, waving wadded-up handkerchiefs to the sky. Some stood, placing their hands on the shoulders or backs of the others. Their murmuring and crying pushed at Justine, but she stayed firmly planted in her seat, rubbing the scar between her left thumb and pointer finger.

After a time, three deacons started down the aisle toward her. She’d been weepy since she sat down, but she quickly wiped her eyes. Uncle Thorpe pushed himself up off the altar and started down the aisle. The band kicked into high gear, banging out the rhythm of Justine’s dormant salvation. Justine swore she could feel the little wooden church shake as Uncle Thorpe strode toward her.

“Playing you their war song,” John Joseph nearly yelled into Justine’s ear. His three brothers made up three-quarters of the band, the piano player the only woman of the bunch. The most gifted musician in the family, John Joseph refused to play in church. Instead, he sat in the back with Justine, who didn’t find his joke funny.

The Saints banged their callused hands on leatherskinned tambourines, working themselves into a hallelujah frenzy that only stopped when Uncle Thorpe set his jaw and said a prayer over a bottle of olive oil. He poured some into each deacon’s upturned hand.

In the hush, Uncle Thorpe hitched his polyester pants high enough to show the green stripe of his tube socks and knelt before Justine. She could have stared a hole through Lula, who now stood dabbing her eyes with a handkerchief in a small group of women behind the deacons.

Justine wasn’t going to bow her head. Couldn’t. Not if she wanted Six Flags. She knew that the minute she started to pray, she would lose her nerve. Who knew what she might say if she let herself go. Brother Eldon, the deacon with the bushy eyebrows angled into a permanent scowl, was already beginning to speak in tongues and squeeze her shoulder too hard.

“I pray you’ll save this young woman, Lord, who is old enough now to know you, Great God, and therefore to deny you,” Uncle Thorpe began in his down-low prayer cadence that always went straight to Justine’s insides. She hoped he’d finished, but then he shouted, “Show her your glory, Lord!” The band took off again, vamped into “I Come to the Garden Alone,” her granny’s favorite song.

Playing that song right now was a dirty trick, and they knew it. Her granny sat up front in the perpendicular pews reserved for deacons and elders. Justine could see her face, could see her arthritic brown hands curled on her knees. Granny sometimes kept her hearing aids turned down during services, and Justine wondered if they were on now. She wondered if Lula had told her about Six Flags.

“Keep Justine from this world and the sins within, Lord,” Uncle Thorpe shouted. The band picked up the pace until her granny’s slow, mournful hymn sounded more like the Stones. People were beginning to convulse and shout, as the Holy Spirit took charge of their mouths and bodies. “Help her to make choices with her body and mind, Lord, that lead her closer to you.”

Justine kept her eyes on Lula, but tears began to roll down her cheeks. She wiped her face, angry that they would think they were getting to her, ashamed of the night that had led her to this moment, maybe even more ashamed that Granny would think Justine chose an amusement park—or worse, her father—over her own mother. Her mother—who’d had to quit art school when he left, who had to stand in line for the government commodities she’d always wanted to feel above, whose artist’s fingers ballooned with blisters from the first job she’d found at a shoestring potato factory.

She thought about trying to pray. Maybe God would be there and would show her a way. The thought had hardly formed when Brother Eldon pressed her head downward, as if by putting her head in the right position he could force words into her heart and out of her mouth. Furious, she cut her eyes at John Joseph, who chomped his gum, unmoved by his father and the deacons.

Justine felt her lip quivering, but then John Joseph blew a big pink bubble and smirked—for her, she knew. He was her cousin, but she could have kissed him.

4.

When Justine heard two honks from the big horn, she looked around the empty house and felt a sorrow she couldn’t explain. She brushed off the hungry cat and climbed into a running Lincoln with whitewall tires, her father a stranger in a car full of strangers. She couldn’t think of a time she’d felt more affection for her mother.

There was a minute—the boy was asleep, and she’d thought that his mom was—when Justine caught a flash of what it had been like before her father left. She remembered how special it had been for one of the girls to be chosen to run an errand with him, to stand in middle of the seat next to him and have him put the flat of his hand against her chest as he came to a stop. In the steady hum of the wheels and road, she quit worrying about how Lula would feel when she got home from work and saw that Justine had gone through with the trip. From her place in the passenger-side back seat, she watched her dad adjusting his fingers on the steering wheel, tensing his jaw. She saw the razor burn on the back of his neck and remembered rubbing her fingers along the stubble when he held her in the rocking chair. She’d spent years pretending that dream of him away, and now here he was driving her down the interstate in a new car, a blonde wife sleeping at his side. Before she could catch the words falling from her mouth, she said, “You didn’t even call.” He didn’t understand what she’d said, so he looked back over his shoulder with raised eyebrows. Now she’d have to repeat herself. “Why didn’t you at least help us?” she said, a little louder.

At that, her stepmother raised her head, yawned, and blinked around the car. “Oh, honey, you know your mama is plumb crazy.” Justine closed her eyes and pressed her forehead to the window glass, praying as she never had before for God to keep her from putting her hands on another person’s body, lest she kill her stepmother where she sat.

The trip was downhill from there, no fiery redemption. Justine hardly said another word the rest of the drive to Texas, certain that Uncle Thorpe’s premonition was right and that no matter her motives she would die a wretched soul on a roller coaster. Her father’s boy was sticky and kept pulling her hair; her father was awkward and overly polite. The stepmother (if the woman who had disappeared your father, the car, and the bank account could be considered a mother of any sort) wore gold rings and a crop top that showed her freckled chest. She made a big show of feeling sorry for Justine in her long dress.

By the time they got there, Justine felt so nauseous and frightened of dying and going to hell that Six Flags was one of the worst days of her life. She threw up on her father’s shoes while waiting in line for Big Bend, and one of the ticket takers told her she was not allowed to ride because “vomit at these speeds ain’t pretty.” Her stepmother took Justine’s place in line, and Justine held her half brother’s hand as she watched her father and stepmother click up the near-vertical roller coaster track and disappear in joyful screams. She thought her nausea was from fear.

5.

Though she was fifteen and a bonerack, she started showing late. So when it came time to start school that fall, all she knew was that she hadn’t felt right since the day she first talked to her father on the phone. She didn’t let herself think of any reasons beyond that. She started sitting next to Lula in church, leaving John Joseph in the back to trim his nails with his pocketknife and break wind without an audience.

She’d avoided Russell Gibson since the night she snuck out with him. He’d asked John Joseph to have her call him, as if they were merely two star-crossed lovers, but she cut John Joseph off before he could get the words out. She wanted to forget, and she’d almost been successful with the summer so full of Six Flags and penance.

But then for two days straight she couldn’t eat lunch or make it through Ms. Peterson’s fifth-period Algebra 2 class without running to the bathroom to vomit. On the third day, Nurse Sixkiller waited outside the bathroom. Justine was still wiping her face with a rough brown paper towel she’d wet in the sink when the nurse put her wide palm to Justine’s forehead.

“You’re not warm,” she said. “Clammy, maybe.”

Justine tried to push past Nurse Sixkiller and return to class, but the woman had that way of holding down the Earth. She would not budge. Justine acted like she didn’t care about her place at the top of the class, but that was the only thing that kept Lula from putting her in the church school, which she would surely graduate from in no time and be ready . . . for what? Marriage? Justine was no longer interested in a man or boy of any sort. “Ms. Peterson’s going to be upset,” she said.

“Have you eaten?”

Justine shook her head. Nurse Sixkiller took her in with her warm, brown eyes, head to toe and back to belly, before leading her into her office and closing the door. “When was your last period?”

Justine shrugged.

“You don’t keep track?”

Dee and Josie, who’d been getting ready to marry or graduate around the time Justine needed to learn about such things, probably thought Lula had talked to her like she’d talked to them. But Justine’s Lula wasn’t their Lula. She hadn’t told Justine anything.

Nurse Sixkiller handed her a small pocket calendar with a ridiculous yellow smiley face on it. “I want you to mark the day you start from here on out.” She didn’t let go of the calendar until Justine looked up at her. “Let me know?” She seemed finished but then: “Your family is Holiness, right?”

Justine held up the hem of her long skirt and sighed.

“Well, you need to go to the clinic anyway. If you need me to talk to your mom with you . . . or if need be, I can take you to the Indian Hospital. Do you know what you want to do?”

Justine grew hollow. She felt as if all of her insides were spilling out, and she cupped her tight belly to check. Around her, the white-and-green tile floor shifted. She wondered if she might fall, but Nurse Sixkiller placed a hand against the small of her back and kept talking.

“I want you to know there’s a doctor in Tulsa. He will take what money you can pay.”

Justine was out the door before she heard the rest. She understood what the nurse was getting at. She kept going down the hallway and out the big metal doors, leaving her open algebra book on the desk in the back row of Ms. Peterson’s class for good.

6.

When Justine walked in the door and smelled frying wild onions and salt pork, she felt as if she hadn’t eaten in a year. Granny turned from her work over the propane stove and smiled. “Always know when it’s ready, an’it? Rinse this,” Granny said, flapping two old bread bags at Justine. “And get plates.”

Justine washed the bags that had held frozen spring onions and hung them inside out. Then she got hot sauce from the cabinets and a bottle of Dr Pepper, Granny’s favorite indulgence, from the icebox.

“Think there’s beans left in there,” Granny said. “No school?” She handed Justine the plate of pork and began breaking eggs into the cast-iron skillet on top of the long, skinny onions.

“I didn’t feel good.”

“You call Lula’s work?”

“Not yet.”

“Eat. Then better call.” Granny sat down with the wild onions and scrambled eggs, but she didn’t begin to eat. Justine felt the silence between them more than she heard it. She put her fork down on the table and took a deep breath. Granny tilted the hot sauce toward her. When Justine waved it off, Granny asked, “Sick a lot?”

Justine’s heart sank. Had someone stuck a sign to her back? Why had her body chosen today to reveal her secrets to the world? Or maybe it had been blabbing for some time to anybody who cared to listen.

“You okay?”

Justine shook her head.

“Been a long time?”

Justine shrugged.

Granny adjusted her hearing aid, seemed to be thinking. Finally she said, “There’s medicine, but maybe it’s too long already.” She paused again. “I don’t remember where to find it anymore. Celia knows maybe.”

“Before summer,” Justine said. Granny spooned food onto her plate and opened the hot sauce.

“Too long, I think,” she said. “Somebody hurt you?”

Justine couldn’t lie to her, so she said nothing. She hoped Granny would go on eating, but the room grew quiet. Granny covered her mouth with her hand. Grease had made the deep ridges of her nails and swollen knuckles shiny. She took off her glasses and began to wipe her eyes with a dish towel.

Justine could not see Granny cry. She pushed herself away from the table, walked out the door, and began to run in the hot sun. At the road, she turned west and kept going. She did not stop until she came to Little Locust Creek. She took off her shoes and sat on the edge of the bank, crying until her body stopped making tears and the sound of her dry-socket wails made her lonely. Then she wiped her eyes on her blouse and hugged her knees into her chest, seeing where she was for the first time. It had been dark, but this was where he had stopped the car.

On the far side of the creek, seven buzzards filled a tree whose dead, gray branches spidered into the sky. The great black birds eyed her and ruffled themselves from time to time but were mostly content opening their lazy wings to the sun. She put her feet in the cool water and flipped rocks with her toes, watching red crawdads skitter away into the deep. She felt like a crawdad today. She’d run from Nurse Sixkiller, a kind woman only trying to help, and now she’d run from Granny, who Justine loved as if she were an extension of her own heart. A fat, nearly black cottonmouth S’ed across from the buzzard’s side of the creek, holding its bully head high above the water. Justine grabbed a stick and stood, waving it over her head, stomping and screaming at the snake to leave her be. It drew near and opened its white maw until it saw that she was a crazy creature not worth fooling with. Then it turned and went back through the pool and disappeared into the weeds along the bank.

Justine sat back down. She made sure that the snake was gone and checked in on the buzzards before she bowed her head and started at the beginning. Not her first birth, but her second, when her father left and they lost their car and their house and Lula had her first nervous breakdown, all at once like that, leaving eight-year-old Justine and her two big sisters to pack their piddly boxes and figure out a way to get them to Granny’s house on their own. It wasn’t fair that her mom had to drop out of college, that they had to eat powdered commodity eggs and fight over the cheese, that they hadn’t had bacon since he left, or that Granny had to share her room with Lula. It wasn’t fair that Justine was one of the best athletes in her class but couldn’t join the basketball team because men would see her legs. It wasn’t fair that Justine had caused one of Lula’s nervous breakdowns herself or that in the midst of it, Lula, out of her mind, had whipped Justine so badly that she couldn’t sleep under a sheet. It wasn’t fair that Justine was made to fear for her soul over a Beatles album or a stupid roller coaster she didn’t even get to ride. It wasn’t fair that she was so angry over it all when every little thought she had would probably require forgiveness. She was just a girl, and she told God so. She didn’t know what to do next, so she kept talking. Sometimes she yelled.

She went on so long that when she heard a big engine rumbling and opened her eyes, the world went white for a minute. When she could focus, she saw an ancient Chevy truck easing into the creek from the two-track on the far bank. The engine cut off, and two little kids stripped out of their clothes and clambered out of the truck bed. A woman and a man, both laughing about something he said, stepped out of the truck too. As the woman tied up her skirt, she grinned at Justine and waved, “Siyo!” Then she called for the man, who was already splashing the kids, to get back over there. The woman spoke Cherokee, but Justine knew she was telling him to grab a bucket and some rags and help her. While the woman and man soaped the truck, the two little kids found the deep hole and dove for rocks.

“There’s a cottonmouth over there,” Justine said and pointed toward the kids. The woman and man left their buckets and ran toward the kids. “Where at?” the woman called, once the kids were hanging from their hips.

“It came after me a while ago, but I scared it off back over there where they’re playing.”

“Wado,” the woman said, no longer worried. She directed the kids to play in the shallows in front of the truck and went back to her bucket. The man scanned the bank for a minute before kicking water at the little kids and getting his bucket too.

After the commotion, the giggling kids crept over to Justine. The tallest, a girl, held a minnow in her cupped hands. “Hey, girl, if you swallow this, you will swim fast-fast,” she said and passed the minnow in a handful of water to Justine. The fish flitted about the palms of her hands, tickling.

“Better not,” Justine said. “I have a long ways to walk today, and flippers won’t do me any good.”

“I already ate one. He’s scared,” the girl said, rolling her eyes at her little brother. She took the minnow back. “Guess I got to eat this one, too, and be the fastest swimmer in the world.” The kids splashed back toward the truck, the little boy unsure if the trick was to get him to eat the minnow or not eat the minnow.

Justine watched the family while the sun worked its way over the buzzard tree. Soap bubbles floated past her on brown water headed through town to Lake Tenkiller. She almost offered to tie up her skirt and help, but the family seemed to work together so perfectly, voices sometimes serious or sharp but mostly full of joy or humor, that she felt happy to watch them, same as the buzzards in the tree and the crawdads in the pools and the snake from wherever. Finally, she stood and waved to them. The kids, wrapped in towels on the hood of the truck eating watermelon, grinned.

Justine told the crawdads she was sorry for wrecking their homes, nodded a solemn goodbye to the buzzards, and spit at the snake. She looked back toward the road she’d come from but decided to try the dirt trail that lined the creek. Though she’d never been down it, great sycamores and cottonwoods shaded the way. She started in the direction of town, unsure if the trail went all the way or if she’d have to cut across somebody’s pasture to get back to a road. Even in the shade, her clothes dripped with sweat, the air heavy with the water it absorbed from the tea-colored creek with its sedges and lizard tails. Soon the trail gave way to weeds and briars, and she could hardly see her feet. She kept going, though her heart pounded in fear of stepping on a snake. She was beginning to wonder if she’d ever get back to town when she came upon a frazzled rope swing over shallow water that told her where she was. This was where the church gathered for baptisms. She and John Joseph used to come down here when they were kids and could get away with sneaking off during camp meeting. She knelt before the creek and rinsed her face in the cool water. Big yellow grasshoppers thunked against her legs as she followed a side trail up the hill to the row of trees that surrounded the church.

She stood behind a shagbark hickory watching people file in for Wednesday night service. After nearly everyone had arrived, John Joseph pulled up with Granny and Lula in his old Ford Falcon. When Lula got out, she approached the few people remaining outside. Justine could tell by the way men clasped both hands around Lula’s and how women hugged her that she was asking them if they’d seen her. Justine should have gone back home or gone on into the service, filthy though she was, but she felt as if a powerful force kept her there watching. After everyone else had gone inside, Lula stood before the open church doorway, scanning the field before her, as if that weren’t the last place Justine would go if she had run away. Except here she was, and unbeknownst to Lula, the only earthly things between them were the fireflies beginning to flash before a row of oak trees and one lone shagbark hickory. Finally, Lula turned and went into the bright doorway and closed the door.

7.

Justine waded through the fireflies and weeds to a yellow-lit church window where a fan rattled and shielded her peeping. Inside, people hurried to shake hands or pass sticks of gum. Little children squirmed, and mothers fanned them or unfolded quilts beneath the pews so they could rest when the service stretched into the night. As the piano player tried to cut off the guitar player’s noodling with the opening chords of a song, a little cousin ran from her mom and jumped onto Granny’s lap. Justine felt a fondness for it all that she’d never been free to feel.

Uncle Thorpe shook hands with a traveling preacher, a man Justine remembered from years back who’d preached a good sermon that had spoken to her in a not-frightening way. Brother Eldon left his spot at the head of the deacon pew and greeted them solemnly. Justine could see Brother Eldon shift his great eyebrows at the other deacons, and instead of returning to his seat, he headed down the aisle toward the church office. The other deacons rose one by one and walked in a line of earth-toned polyester pants and plain long-sleeved button-ups after him. Brother Shane, the young, kind-faced deacon, whispered in Lula’s ear, and Lula, after checking the back door again, got up. She slowly draped her purse over her shoulder, tucked her Bible under her arm, and followed him.

“Busted, cousin,” John Joseph whispered. Justine nearly jumped through the window. He leaned next to her, digging into his front pants pocket for a pack of cigarettes, grinning. He pulled one out, stepped downwind from the window, and lit it. “Why’d you bug out?”

“It’s crazy,” Justine said.

“Reckon so.” He swiped his black hair out of his eyes and offered her the cigarettes. She waved them off. He raised his eyebrows and slid the pack back into his pocket.

“You’re getting brave. Or stupid. Uncle Thorpe’s going to beat you up one side and down the other.”

“Wouldn’t be the first time.” He cupped his hand around the cigarette, took a drag. “Might be the last.”

“What’s going on with Brother Eldon and them? Why’d they come get Mama?”

“Can’t be good.” John Joseph shrugged. “You need to talk to her. She’s going to lose it again.”

Justine couldn’t believe she’d come to church of all places. For months, she’d been drifting along as her insides turned decisive and took charge, driving every decision that would follow. Then she’d let her feet carry her here because that’s what they’d been trained to do. She thought about running again. Once she got home, she could pack a bag and go. Somewhere. To her dad’s? He might not want her there but probably wouldn’t be able to turn her away. She wasn’t afraid to hitch. She wasn’t afraid of work, either, would sooner break her own bones than admit she couldn’t do something. Then what? Her bones no longer felt like hers to break. But she had time to save up for a place, maybe, if she could get someone to hire her. The thought of asking her bronzed stepmother for help sent a fire through her chest.

Up front, the service was starting. Justine squatted down again and peered inside, wondering if she should go on in. Maybe she’d get something out of it, some direction or at least a chance to rest her blistered feet. Uncle Thorpe introduced the traveling preacher and then walked down the same aisle as the deacons and Lula. Granny sat in her pew watching him go. She whispered to an old woman next to her, and the woman shook her head. Granny waited a minute; then she took the little cousin to her mom and headed down the aisle as the service started up around her.

“I’ve got to go check on Mama,” Justine said, nearly running over John Joseph as she started around the side of the church. She pushed into the glass door and stopped still before Uncle Thorpe’s office. She’d never been inside before. She took a deep breath, turned the knob, and went in.

Uncle Thorpe sat behind his wooden desk, the deacons standing in a half circle behind him. Lula sat in the lone chair across from them. Granny pressed a hand on Lula’s shoulder, a mountain. Lula’s skirt had somehow become caught in the top of one of her knee-high stockings and flopped over, showing a small V of her knee. Justine was so startled at the sight of her mother’s knee that she almost turned and walked out. Nobody else seemed to have noticed. Lula’s face grew pale as she studied Justine. Justine knew then that Lula must have been the only one who hadn’t seen what was happening until now.

“Has the devil had his way with you, Justine?” Brother Eldon said. He looked like a mean old eagle.

Justine put her hand to her belly, and Lula reached out and called, “My sweet baby.” Justine took a step away from Lula. She didn’t have to go to her dad’s. She could just go.

“It’s not right having a Sunday school teacher with an unwed pregnant daughter,” Brother Eldon said. “What does that say to the congregation and other churches?” His face grew red as he spoke. “I don’t think it speaks well of us to have a pregnant girl in the church at all.”

“Brother Eldon.” Uncle Thorpe put his thumb on his temple and began to pinch his forehead. He took a deep breath. “The deacons are excused.”

“We’ve discussed this,” Brother Eldon said.

“Give us some time, Brother,” Uncle Thorpe said. “Mama, we’ll be okay. You can go on, too.”

Granny stood her ground until the last deacon was out the door. Then she leaned down and kissed Lula’s head before she squeezed Justine’s hand. “I’ll be outside, u-we-tsi,” she said to Uncle Thorpe. Her voice was sharp and left no room for discussion.

Lula didn’t seem to register Granny closing the door. She began to smooth her skirt, oddly focused on the folds of the fabric.

“Do you know who the father is, Justine?” Uncle Thorpe asked.

Justine didn’t answer, didn’t have time to feel angry or embarrassed at the insinuation. She was watching Lula, who had begun to rock her shoulders from side to side and hum.

This church was all she had. People respected her testimony, her voice, the songs she wrote, the murals she’d painted in the nursery. She could elaborate on any Bible verse as well as a deacon, maybe as well as Uncle Thorpe. People admired her resilience, which to Justine seemed the funny thing about faith. The bigger your obstacle, the greater your heavenly blessing. Lula would be truly blessed.

The night Lula learned Justine’s father was not dead in an accident, just gone, neighbors found her at 3:00 a.m. wandering around in her nightgown. She couldn’t talk for days afterward, never quite got her pieces put back together right. She’d married him right out of Chilocco, and the church considered him Lula’s husband in God’s eyes until he died, no matter how many other women he married or how far he roamed. Her house—when she had a house—used to be full of girls and a husband. One by one, they had left.

Justine had fought her at every turn. It might as well have been written. Justine wasn’t her sisters, wasn’t wired to go along with things for the sake of comfort. In that way, she was as religious as Lula. When she stopped fighting her mother long enough, Justine understood her. And now, because of Justine, Lula might lose the church too.

“It’s okay, Mama,” she said. She moved to Lula and put her arm around her. “It’s going to be okay.”

“Who’s the baby’s father?” Uncle Thorpe asked again.

Justine ignored him. She put her hands around Lula’s cheeks and pulled her face to hers. “I’ll get my GED and get a job. I’ll get two. We’ll be fine, Mama.”

“How?”

“I don’t have an answer for that, Mama. But there is a baby in here. It’s true. I’ve felt it moving.” Justine smiled, but her tears were starting up too. “This baby is coming, Mama. It doesn’t matter what the deacons say. I’ve been praying, and God knows what he needs to know. That’s all I’m going to say, except I’m sorry for the trouble it’s causing you.”

She couldn’t have told herself why she wouldn’t say his name. Maybe she still thought this was all her fault for sneaking out and for every little bad thing God had tallied over the course of her life. She hadn’t asked for what happened, but if there was one thing she’d taken from the nights she’d spent in the pews of Beulah Springs Holiness Church, it was that the Lord worked in mysterious ways. Regardless, the deacons might pressure her to marry him. After all, it was she who had opened her window that night and run down the hill to his waiting car. They might do an okay job of pressuring him too. And then she’d be married to a son of a bitch who made her sick to her stomach, a man who’d already shown her he was stronger than she was. She wouldn’t let it happen again.

Things would be simpler if she kept the focus on this baby. Maybe that was as far as her young mind could stretch, as much as it could handle. As far as she was concerned at that moment, the father didn’t exist, nor did that night. She was simply a girl, or had been, and now there was a baby, immaculate as could be.

Uncle Thorpe poured olive oil into his hands, put them over each of their heads, and prayed over them. Justine didn’t mind for once that her hair would be oily. She let her mind settle into Uncle Thorpe’s words. She figured she needed all the help she could get. When he finished, Uncle Thorpe wiped his eyes and hugged them.

“Maybe you two should spend the evening sorting things out at home. I’ll bring Mama home. You can take John Joseph’s car.”

Justine was gathering Lula’s purse when Lula hugged it back into her belly.

“We won’t go,” she said.

“Won’t go where?” Uncle Thorpe asked.

“We won’t go home. The Lord’s house is home, where we need to be.”

“I thought you would want to sort things out, Sister Lu.”

“Justine is having a baby. It is sorted.” She stood and picked up her Bible from his desk. “I won’t have us thrown out of here like trash by Brother Eldon.”

“He’s worried about factions in the church, Sister. You know how he gets.”

“I know how he talked to my daughter like trash, and I won’t have it. From anyone.” She turned to Justine. “It’s going to be alright, Justine. You’re right about that. God holds us in his hands even when we feel the farthest from him. We can do whatever we have to do. If you want to go back to the service, let’s go. Only God can make our way. If you want to go home, I think that will be fine. God will be with us where we are.”

“Let’s just go, Mama. I don’t want to cause any more mess.”

“Your decision.”

When they walked into the hallway, Granny was sitting in a chair she’d pulled up from one of the classrooms. Lula leaned down and yelled into her ear.

“We’re leaving, Mama. You can stay if you want.”

Granny shook her head, and Justine helped her stand. Uncle Thorpe walked the three of them to the door and said, “I’ll go get John Joseph’s keys.”

“I think he left them in his car,” Justine said, maybe a little too quickly.

Uncle Thorpe studied her for a moment, then squeezed her shoulder and said, “I’ll be praying for you.”

When the three of them got to the other side of the church, John Joseph was still leaning by the window. Now he was listening to the traveling preacher’s sermon. Justine was glad to see he didn’t have a cigarette because she didn’t want to get into a-whole-nother thing with Lula.

“Where’s the party?” John Joseph grinned. Lula tried to scowl, but even she couldn’t pull it off. Granny shook her head. He had always been her favorite, Justine knew. It was okay. He was Justine’s favorite too.

“Can you please take us home, young man?” Lula asked. She smoothed her hair, and Justine noticed that her fingers shook ever so slightly as she tucked a handkerchief into her bag.

“At your service,” John Joseph said. He opened the primer-colored door and pushed the front seat forward so Lula and Justine could squeeze into the back. Then he helped Granny down into the frayed passenger seat.

Uncle Thorpe walked out the back door as John Joseph was backing out. He raised his hand, trying to get John Joseph to stop, but he hit the gas around the corner out of the gravel parking lot. When he did, the car skidded sideways, and Justine slid into the middle of the seat, pressed against Lula.

“John Joseph!” Lula shouted, and Justine laughed. Granny held tightly to the roof outside the rolled-down window and muttered something in Cherokee that Justine couldn’t understand. Lula’s shouting only goaded John Joseph. He pressed the car faster up the big hill into town. The wind whipped in the windows, and Justine forgot for a minute what would happen when they got home and the real questions and shouting and crying began. She couldn’t know how in a few months she’d be flooded with a crippling love for another human being that would wound her for the rest of her days, how her insides would be wiped clean, burdened, and saved by a kid who’d come kicking into this world with Justine’s own blue eyes, a full head of black hair, and lips Justine would swear looked just like a rosebud. For now, that little car filled with three—almost four—generations flew. And when they dropped over the top of the hill, Justine threw her hands up, her mouth agape in wonder.