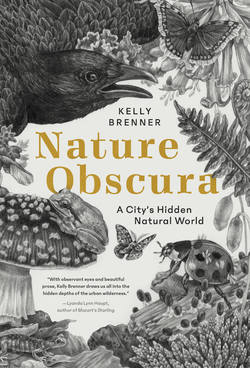

Читать книгу Nature Obscura - Kelly Brenner - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

The Patina of Time

ОглавлениеTo a naturalist nothing is indifferent; the humble moss that creeps upon the stone is equally interesting as the lofty pine which so beautifully adorns the valley or the mountain . . . .

—James Hutton, Theory of the Earth

Before I climbed up onto the railing outside our back door, I first looked around to see if any neighbors were in their yards or walking down the alley. When the coast was clear, I hauled myself up and stood on the railing before stepping across the gap to the roof of our detached garage. I scooted on my backside across the roof, where I lay down, stretched out across the asphalt shingles.

Conventional wisdom says that moss on your roof is bad and that it’ll make the shingles too wet, causing them to rot, or that the roots will lift up the shingles, leading to water damage. A mossy roof is considered an eyesore in the city and better suited to a rustic old cabin in the woods. But I’m curious and tend to question the status quo.

As I lay on my belly, I studied the rows of moss organized neatly along the shingle edges. The moss grew in tiny clumps, no more than a half-inch wide at most. The little green tufts with silver tips were nothing short of adorable, a miniature landscape growing far above the ground. I saw no shingles being forced up into the air, and when I pulled a couple clumps off, they came up easily, without a fight, leaving nothing behind. I couldn’t see any damage at all. As I studied the moss, poking and prodding at it, I began to question whether it really needed to be removed.

The problem, I quickly found, was that there are scant studies conducted on roof moss. Some sources, notably roofing companies, say moss is damaging. Others, like those of the green roof industry, state that moss can be beneficial, protecting shingles from sun damage. But the information on both sides is largely anecdotal. Since there was no consensus, I turned to the person whose name is synonymous with moss: botanist and professor Robin Wall Kimmerer. In her book Gathering Moss, Kimmerer writes that while mosses do produce tiny rhizoids, which are the moss equivalent of roots, she strongly doubts they “could pose a serious threat to a well-built roof.”

And yet, in a city where everything is meticulously maintained and managed, moss defies our modern, neat and tidy landscapes. A mossy roof is a mark of age. We accept moss in the forest or on an ancient stone wall in the country without question, but in the city, we’ve decided it’s unseemly and must be scraped away.

When we moved into our house, I was happy when the moss began spreading under our maple tree. It was pretty, softer to sit on, and didn’t require any maintenance. I considered it a win-win. I’m not alone in thinking a blanket of moss is preferable to the dramatically higher maintenance grass. In recent years the idea of a moss lawn has grown on gardening websites and in books, and now you can buy moss in sheets or as a blended moss and yogurt milkshake to spread out and grow in your garden. But it’s not a new idea; gardeners have used moss as a deliberate design element for almost seven hundred years.

Not far from Seattle is a place that has become famous for its moss garden, and one day I traveled across Puget Sound on the ferry Wenatchee to Bainbridge Island, where the Bloedel Reserve is located. During the passage I stood on the front deck, braced against the cold winter air as I looked for orcas and birds. A few gulls flew overhead along with the ferry, as though escorting it across the Salish Sea.

By the time I’d driven to the Bloedel Reserve, on the opposite end of Bainbridge Island, I had just about warmed up. For more than thirty years the 150-acre reserve was the private landscape of Virginia and Prentice Bloedel. Mr. Bloedel had a complicated relationship with the land; he was heir to his family’s timber business but he was also an environmentalist. Under his leadership, the company was the first to plant seedlings after harvesting the trees. Following his retirement, his connection to the land played out in the Bloedel Reserve, where he frequently walked and worked with landscape architects to form the grounds. Today the reserve contains formal gardens, woodland trails, meadows, and the award-winning Garden Sequence containing four “rooms,” including the Moss Garden.

The Bloedel Reserve’s Moss Garden is legendary not only locally but widely among landscape architects. It’s a place I’d learned about while earning my degree in landscape architecture. I was to meet the garden’s current caretaker, Darren Strenge, and its previous caretaker, Bob Braid—who had tended the Moss Garden since 1985 before handing the reins to Darren and turning to manage the nearby Japanese Garden.

Together, Darren and Bob led me into the Moss Garden, telling me it had been completed in 1982 and was inspired partly by Japanese gardens and partly by the rainforests of the Olympic Peninsula. At two acres, it is the largest public moss garden in the United States. Designed by acclaimed Seattle landscape architect Richard Haag, the Moss Garden, or Anteroom as it is also known, is part of the Garden Sequence, a series of four rooms starting with the Garden of Planes (now a Japanese rock garden) and moving on to the Anteroom, the Reflection Garden, and the Bird Refuge.

Not only was the idea of a moss garden unique when it was designed, but entire dead logs and stumps were brought in and left to rot in place, to be claimed by moss. Initially, 275,000 plugs of Irish moss (not a moss at all, but a perennial plant) were planted until native mosses took over. And they did, until the garden became a mosaic of varying shades of green containing more than forty species of moss with almost none of the original Irish moss remaining, outcompeted by the native moss.

Throughout the garden, moss-covered mounds of vague, fuzzy shapes—remnants of the original logs—slowly collapse in on themselves as they gradually rot. Bob told me that Mr. Bloedel was fascinated by these stumps and nurse logs. Native plants such as sword fern, evergreen huckleberry, and salal grew on some of the stumps and logs while along the southern edge of the garden, the thorny devil’s club marked the border. Old western red cedars towered over the garden, creating a shifting pattern of light on the ground where the sun filtered through. Moss crept up the flare of the tree trunks, making it hard to distinguish where the ground ended and a tree began.

The more I looked, the more I could begin to detect patterns in the ground. It was not a simple blanket of green, but a complex tapestry of many tones, some tending toward blue, others tipping to yellow. In between the greens stood patches of rust from the reddish capsules of common smoothcap moss. But the pattern isn’t random, and to know the mosses is to understand the various microclimates they favor. Some species are tolerant of the sun and boldly grow where no other mosses dare to creep. Others crowd around the soggier parts of the landscape, wanting to keep their toes constantly wet. Some live high, hanging on the branches of trees and never touching the ground. A few grow side by side, competing in a slow-motion struggle to gain more ground.

As we walked through the moss garden, Darren occasionally hopped off the path to pluck out various species, and I could easily feel his connection to the outdoors. He’s been working at the reserve since 1997 when he decided, after finishing his master’s in botany and working in a lab studying pollen fertility, that he’d rather spend his days outdoors than in a laboratory. He has been getting to know the reserve ever since, and the Moss Garden in particular, after he took over its care in 2017. At one point on our tour, he leaned down over a bed of green, teased out a single tiny plant, and handed it to me. He said it’s called Menzies’ tree moss, and I could easily see why. The foliage of the “tree” sat atop a long, brown stem, reminiscent of a trunk. The slender leaves radiated down along arching “branches,” and as a whole it looked like a miniature tropical tree. However, unlike a tree, the plant had two thin stalks protruding from the top. These setae, part of the moss’s reproducing sporophyte, were red at the base, with the color shifting in gradients to green at the top, where two bright green, oval-shaped capsules sat, nodding downward, nearly ready to release their spores.

Next Darren handed me snake moss, which he said he liked showing to visiting kids. One after another, he pulled up tiny, individual plants of different mosses, and as they started to accumulate on my notebook, I could see how different they were one from the other when removed from their mats. One stood at least four inches tall with dark green, swordlike leaves. Another sprawled seaweed-like in a tangle of bright green, and still another looked like a feather taken from a parrot. They were all green, but the textures and variations of green were astonishing.

To describe the garden as a carpet would be a disservice because it looked much softer than any human-made carpet. The temptation to feel that soft, damp green on my feet was irresistible, and I joked to Darren that I would love to take my shoes and socks off and walk through it. He replied that he actually does that sometimes, when no one is around. I don’t think he was joking.

Once Darren and Bob left me to return to their duties, I retraced my steps back to the beginning of the Moss Garden, where two moss-covered rocks stood as guardians, to walk through the garden again, alone, in the quiet of the reserve. But what I didn’t realize was that I was starting my walk out of order, in the second room of the Garden Sequence. I had missed the first room.

Richard Haag, who designed the Garden Sequence at the Bloedel Reserve, had long been attached to the Pacific Northwest, spending most of his professional life in Seattle. He designed landscapes in the region but also around the world, as well as founding the landscape architecture program at the University of Washington, before he was chosen to shape these acres of formerly logged land.

The Garden Sequence begins in what was once the Garden of Planes, adjacent to the Moss Garden, but the start of the sequence no longer exists, as I would find out at the end of my walk when I visited the first room last. Originally the Moss Garden was a bog overgrown with pink-flowered salmonberries, and the tiny rivulets of water forking through the moss are evidence today of that bog. Haag said this garden was “created by selective subtractions of the nuances of nature from the chaos of a tangled bog,” reflecting a trademark of his design style. Here, as in another of his famous landscapes, Gas Works Park in Seattle, Haag liked to leave traces of the landscape’s history. By leaving the enormous downed logs, he recognized the history of logging in this place while contrasting it with the surrounding second-growth forest. By removing the undergrowth and leaving the trees and the ancient logs to be claimed by moss, Haag created a space that breaks free of any traditional landscape style.

The towering western hemlock trees, the bare roots tipped up vertically, the decay and decomposition, the damp earth, and the intimacy of the space make the garden feel primordial, as it’s often described today. It’s a walk back in time, where the ghosts of 700-year-old trees, gone for a hundred years, remain in the shapes under the moss.

Coming to the end of the Moss Garden, I stepped out of one room and into the most iconic place in the reserve, the Reflection Garden. In this room, set in grass, is a long, rectangular pool surrounded by a long, rectangular yew hedge. The room sits, almost impossibly, surrounded by towering trees, which are reflected in the smooth water. Linear, simple, obviously human made, it’s the opposite of the Moss Garden. And yet it complements the previous room with its green hues and lofty trees. Haag designed the Garden Sequence this way intentionally; the four rooms alternate between the obviously crafted to the more natural, although still heavily cultivated, spaces. They complement one another and lead the visitor through a pattern of interpreting nature in different ways.

Leaving the Reflection Garden, I wandered aimlessly along a wooded path, and while the ground wasn’t covered in moss, it still grew in thick patches along Douglas fir trunks and mixed in with licorice ferns. I crossed the road again and entered the lower portion of the Japanese Garden, not part of the Garden Sequence, where I found two ponds, one large and one small, split in half by a walkway. Along the undulating edges of the water, large boulders grew sweaters of moss and lichens, and a wooden bench sprouted moss from its corners. The smaller pond, punctuated with traditionally pruned pines and Japanese maples, reflected the image of the guesthouse perched on the hill above. The building is beautiful, with wide glass windows and a glass roof supported by large wood timbers—a merging of Japanese and Pacific Northwest design styles. Walking farther, I ended up at a Japanese rock garden—what used to be the Garden of Planes—situated behind the guesthouse at the top of the Japanese Garden.

Echoing the form of the Reflection Garden, a long, rectangular rock garden dominates the space. Nestled in the raked sand are two clusters of boulders, and surrounding the garden is a checkerboard of alternating squares of concrete stepping-stones and grass. The rectangular garden was originally a swimming pool before Haag’s redesign filled it with two pyramid shapes—one inverted and extending down into the former pool interior and the other rising up within that space right beside it. This was his Garden of Planes. Haag first envisioned the pyramids becoming slowly colonized by mosses. The surrounding checkerboard did not originally include grass, but moss squares alternating with the concrete stepping-stones.

Sadly, or perhaps ironically, the very year Haag won the prestigious President’s Award of Excellence from the American Society of Landscape Architects for his Garden Sequence design, the Garden of Planes was replaced with the rock garden and his Garden Sequence forever broken. According to Haag in an interview in Landscape Architecture Magazine, one reason, besides some internal politics, was because a fox had a den under a nearby stump and “every morning, the fox would come out and leave his morning offering right on top of the gravel pyramid.”

As I wandered around the rock garden, I noticed that the concrete stepping-stones were slowly being consumed by moss. The large boulders were similarly being enveloped by thick green clumps. After I had made my way through the reserve’s gardens, one fact seemed clear: moss simply grows, mindless of the grand designs of any human.

Having spent time in Japan, Richard Haag likely took inspiration for the Bloedel Reserve’s Anteroom from one of the world’s best-known moss gardens: Saiho-ji, in Kyoto. While Saiho-ji was first built hundreds of years ago, it wasn’t until after it fell into neglect and mosses claimed it that Buddhist monk Muso Soske embraced moss as part of the garden and experience. Today moss is a standard element in traditional Japanese garden design worldwide, including at the Seattle Japanese Garden.

I had been granted permission to visit the Seattle Japanese Garden during its annual winter closure, a time that allows the landscape crew to undertake major work. It wasn’t my first visit, but it was my first winter visit. The morning I arrived, a couple of weeks after I had visited the Bloedel Reserve, the weather was cold and crisp, with frost lining the grass and the edges of fallen leaves. My guide for this visit was Pete Putnicki, senior gardener at the Seattle Japanese Garden. Although Pete had only been the head gardener for a couple of years, he is intimately knowledgeable about the garden and has a tremendous eye for detail.

As we walked through the back gate and into the garden, he explained that while the mosses may look effortless to maintain, they’re really not. In autumn the crew must rake the leaves fallen from the garden’s many Japanese maples and other trees to prevent the leaves from damaging the mosses. Metal rakes can pull the moss out of the ground, so the crew uses traditional Japanese bamboo rakes to sweep up leaves and other debris, a slow, delicate process.

Pete pointed to a patch of moss with a rusty tinge and told me that this moss is one of their favorites in the garden: Sugi moss. Also known as Sugi-goke, meaning cryptomeria moss, it is popular in Japanese gardens. The name comes from the moss’s resemblance to the Japanese cedar tree, Cryptomeria japonica. When pulled out from the dense mat, the individual plant looks uncannily like a miniature cedar tree. Part of the appeal of Sugi moss in the garden is its tolerance of the conditions in Seattle, where the groundcover withstands the wear from raking and changes colors during the year from bright green to red and green when the red-stemmed capsules sprout.

We squatted down to take a closer look at the Sugi moss, and as Pete talked about encouraging this particular moss to grow, he rubbed his hand over the red capsules, sending a cloud of spores into the cold morning air. It was easy to see how the moss spreads on its own, with spores so small and light.

Still, some of the garden’s mosses were intentionally planted, and that winter break, the crew had been doing just that. They had shifted the main path slightly and added a rope barrier here and there, leaving behind bare patches of soil. They had collected moss from other parts of the garden, mostly areas out of view along the fence, and set the moss out in little clumps, right on the soil, like cookies set on a baking sheet. According to Pete, in only three years the moss will have spread enough to cover the bare soil and in only five years will look as if it has always been there.

Next we made our way up the stone stairway to the tea garden, a small fenced-off area open to the public only for weekly tea ceremonies. The tea garden was designed to feel as if it’s set deep in the woods, and as we walked up the boulder-lined steps, Pete explained that there are no cut stones in this part of the garden—they are all natural. Pointing out the moss growing in thick mounds between the stone steps and up along their edges, he commented that although this garden was built in 1960, the moss adds a patina that makes it appear much older. At the top of the stairs we headed to the left, where a series of stepping-stones set in a sea of moss leads to the teahouse. Slowly, I tiptoed from stone to stone, balancing carefully after each deliberate step so as not to tread on any moss. The uncomfortable placement of stones is intentional, serving to slow visitors down, encouraging mindfulness and focus as we pay more attention to our surroundings and the moment.

The moss sprouting up between the stones was a deliberate part of the garden, a desired urban patina. Some of it had been intentionally planted and gently managed, but moss is going to grow where it will. Maybe it’s time we embrace it.