Читать книгу Urban Farm Projects - Kelly Wood - Страница 4

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

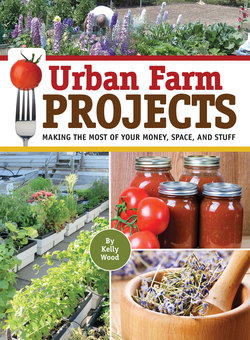

ОглавлениеIntroduction

Receive a fish, eat for a day. Learn how to fish, eat for a lifetime.

—Variation on an ancient proverb

It seems that going hand in hand with the current technological revolution is widespread nostalgia for the past. There is renewed interest in self-sufficiency through traditional farm-style practices, and increasing demand for space in which to garden or raise livestock in close proximity to urban amenities. Many people realize that these practices can be done in smaller dwellings and on urban plots instead of solely on rural acreage. More of us are rethinking how and where food can be grown, leading to a surge in innovation and ingenuity. It’s a movement toward simplification and getting back to the land while incorporating modern technology to facilitate the process. The challenge is how to optimize this on a functional, daily basis.

Modern life is too full—full of possessions, activities, news, and information. We have electronic screens in our homes, our offices, our cars, and even our pockets. Everywhere we turn, advertisements tout products that we “need” to make us happy and fulfilled. Every new item promises to streamline our lives, yet each one requires accessories and obligations—another power plug, another holder, another monthly fee. More and more, people are seeking less and less—fewer objects, fewer activities, less (or at least better) news, more concise information. We want respite from the busy norm. Because “getting back to basics” differs from many of our current habits, it feels new. But many of these basics have been around for a long, long time.

There was a lot of life before automation. A few generations ago, the majority of American families lived on farms, raising almost all of their own food. Parents needed their children to help run the family farm; in turn, the grown children took over the farm from their aging parents. But far-off cities were growing, and the higher paying jobs, less physical toil, and greater excitement of city life began luring young people away from the farms.

In the early to mid-twentieth century, planners created new sub-urbs (from the Latin for “under” and “city”), which offered this younger population affordable housing with easy proximity to urban jobs. Families were able to live close to cities but still have modest houses and yards for kids and pets. The 1950s postwar American lifestyle, with newfound exuberance and affluence, embodied the quest for ease and leisure, resulting in people embracing “labor-saving” devices for use in the home. Televisions became ubiquitous, and thus marketers discovered a ready audience for their sales pitches.

Despite the influx of tools designed to simplify cooking, there also was a new industry in grocery stores and ready-made foods. It became easier and more stylish to buy a package instead of assembling fresh ingredients to cook from scratch. Advertisers of modern conveniences strove to convince potential buyers that they’d wonder “how they ever lived without it!” There always seemed to be something newer and better to help homemakers or please the kids. Our collective discontent began growing.

Meanwhile, the migration away from family farms reduced the number of able bodies to inherit and work the land. As people aged out of farming and chose to sell their acreage, the fewer remaining farmers consolidated their holdings. These bigger farms needed to keep up with the demand for their products, and labor-saving methods were available to them also. Industrial practices emerged to facilitate running bigger operations, and the family farm became quaint and old-fashioned, left behind in the drive toward large-scale food production.

Many studies have shown how environmental degradation can result from industrial production and processing. Certain practices contribute to the pollution of air, water, and soil, which are the foundations that food sources—plants and livestock—need to grow. When the foundations are unhealthy, the food quality suffers, and then we all suffer. Problems keep surfacing in our food supply; concerns have arisen about how and where food is being grown and raised, and where contaminants are coming from. The “epidemics” of obesity and diabetes demonstrate how the ingredients in processed foods can affect our bodies. More problems mean more need for solutions, and manufacturers are ready to fill this new need. Advertisers again tell us, “You won’t know how you lived without it!” And so the cycle repeats.

Today, more people live in cities than in rural areas, but there is nostalgia for the perceived simplicity of country living, and a renewed appreciation for what small farms provide. People are beginning to understand that “old-fashioned” doesn’t mean “outmoded.” Farm products—think fresh milk and eggs, whole grains, and homegrown produce—and the active processes of raising them are what many city dwellers seek. Some of this desire has come from increased scrutiny of our food-production systems, while many want to return to the way that previous generations ate—freshly prepared meals made from basic, wholesome ingredients.

I am a farmer and a full-time mother. Despite certain perceptions, being a stay-at-home parent does not bring limitless free time. For many of us, it ups the ante to do more because tasks such as laundry, cleaning, grocery shopping, and running errands are just not that mentally stimulating. I enjoy challenges, and I often encounter people who can’t believe my activity level. They speculate that I must never sleep, and they don’t know how they could fit the things I do into their own routines. In our ready-made consumer culture, they think doing things by hand is more difficult—why make it when you can buy it?

The pioneers and settlers who built our country had the same twenty-four-hour days that we have, but they had less time to work because they were beholden to natural cycles for light. They worked hard because they had only their physical strength and ingenuity to help them survive. The infrastructure that we take for granted didn’t exist—they didn’t have cars, paved roads, heavy machinery, electricity, phones, indoor plumbing and heating, convenience stores, garbage collectors, media, or the Internet. Nonetheless, they built sturdy structures, kept in contact with friends and family, drank clean water, prepared flavorful food and beverages, took medicine, kept animals, had social gatherings, grew gardens, preserved food, enjoyed music, cleaned their houses, washed their clothes, and bathed—just like us. And they took every Sunday off.

I have always been a curious person, seldom satisfied with the status quo. How and why are two of my favorite words. I constantly ask myself how things are made, or why I am buying something. There is little I like better than something to take apart or an opportunity to find a different solution. When a commercial or advertiser tells me that I’ll wonder how I ever lived without a certain product, I do exactly that—I wonder how people lived without it. If past generations got the job done without this gadget, how did they do it? Usually, they did just fine. Our great-grandparents grew up without the paraphernalia that we have, but they seem to have been healthier and happier. They made do with less because they knew how to do more. Many of the projects in this book are old practices that our generation has not been taught.

I think we should relearn how things used to be done. If I can buy an item in the store, then someone, somewhere, made it. How is it made? How did it used to be made? Is it something that I can make so I don’t need to buy it or rely on a manufacturer for refills? Could I save time or money by making it? Would it be fun to try? When these questions motivate me to act, I inevitably learn something—either from the research, the process, or the mistakes made. The knowledge is out there to be had, and finding it and applying it are up to you.

I’ve compiled my years of giving in to curiosity in these pages. Although our predecessors worked incredibly hard, I found out that we can make many of the things they did, often more easily and in less time, resulting in healthier, simpler, more rewarding lives.

This book is intended for the average householder. Each project has an introductory page that gives an overview, including any specific skills required. Special equipment is also listed, but you may come up with your own ideas. Depending on how you do something, someone else’s ideal tool might not work for you.

I try to operate on the assumption that you are not interested in accumulating a lot of specialized equipment and would rather use tools and devices that you already own—simplification means more “double-duty” items. Since my family relies on one income, I try to spend as little as possible and avoid superfluous purchases altogether. Don’t buy something new for an activity you might not pursue, and be realistic. Remember, despite convincing advertisements, many “perfect solution” items are not perfect solutions at all—if they were, inventors would stop trying to improve upon them.

Some stores will allow you to “test-drive” an item, meaning that you can try it and return it if you aren’t happy with it, but check their policies first. Or try

borrowing—many people have items that you could use, and someone might even be interested in trying the project with you, using the equipment together, and sharing the resulting yield. This is a great way to meet new people or get together with friends for a fun undertaking.

I have tried every project in this book. My results are not all pretty or perfect, but they are effective. My idea of an accomplishment may differ from yours, just as my definition of “functional” differs from my husband’s perception of “nice to look at.”

Feel free to adapt and adjust the parameters of any project—in other words, experiment! I am not the authority on these topics, and I’ve come up with my own methods through practice. Many of these projects are pretty forgiving, and if I haven’t included exact measurements or recipes, you can safely assume that the process is fairly loose and play with it a bit. If it doesn’t work, don’t give up. Learn from it and try a different approach the next time. You’ll work out what suits you best.

If you’re particularly interested in a project or practice, by all means delve into it further. Resources are out there for anyone who wants to learn; I’ve included a few of my favorites with most of the projects.

You can find more resources online; there are countless websites on most of the topics discussed in this book, with many recipes and formulas to be shared. Also look for more in-depth books on your favorite topics—before you buy, check your local library for books that explain clearly and answer your questions. I have some books that are dog-eared from constant reference, and others I wish I hadn’t wasted money on.

If you try something and decide it’s not for you, at least you will have gained an appreciation for what goes into it. You’ll be especially glad the next time you reach for the product on the shelf, thinking, “Thank goodness I don’t have to make this myself!” It might even inspire you to find a local purveyor who has mastered the craft and makes an exquisite version and who might be willing to give you tips if you want to try the project again.

Humans are social creatures—we cannot do everything for ourselves, but there is a lot we can accomplish on our own. If we make time for what we believe is important, we can derive so much enjoyment from doing instead of having. We can simplify and actively learn simultaneously. When we work hard to achieve something, the outcome is even more fulfilling. We all have the potential for this kind of satisfaction. Give it a try.