Читать книгу The Silent Son - Ken Atkins - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

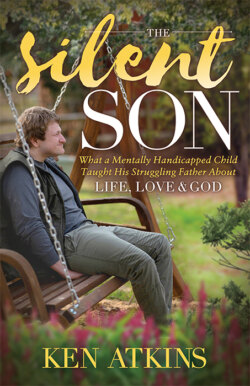

Chapter 1 THE RELUCTANT PARENT

Оглавление“For I know the plans I have for you,” declares the Lord, “plans to prosper you and not harm you, plans to give you hope and a future.”

– Jeremiah 29:11

It is a typical Sunday afternoon. My twenty-six-year-old son is on his twin bed, bent double, with feet on the floor, butt on the edge of the bed and head resting on my office chair, having spent several minutes getting perfectly placed in this very uncomfortable looking resting position. He is paying no attention to the SpongeBob rerun playing on his large screen TV. Oblivious to the world around him, he quietly rubs his thumb back and forth over his mouth, an activity that can occupy hours if left uninterrupted by me or our black cat who wanders in and out looking for someone to hit up for a quick game of swat or a back and head rub.

I am on my twin bed next to his, working the Sunday crossword, both glad for and resigned to the fact that this peace and quiet will last the entire afternoon, as long as I stay in the room with him, even though he seems to be totally unaware of my presence. Experience has taught me that if I leave the room for more than two minutes, he will be banging on the wall, demanding my return, so that he can resume his thumb-licking.

Such is the life of caring for a mentally handicapped person. It can be daunting, physically and emotionally challenging, scary, exhilarating, exhausting, even soul crushing. Mostly it can be incredibly monotonous.

But don’t get me wrong. Raising my son has been the greatest joy and blessing I have ever known. It has taught me to be more patient, less self-centered, more organized, yet less structured. Mostly, it has taught me I can do many, many things I never imagined, but only by the grace and mercy of God.

I write this book as a message of hope and understanding for those who find themselves in this position with no idea what it means. There are no classes or instruction manuals for quick reference. There are lots of ideas, stories and suggestions that you will receive from family, friends, doctors, therapists and unlimited Internet sites. Some of it might even be helpful, but none of it should be accepted without careful examination.

Three things you should know before we start:

1 1.There is no single right way for raising your handicapped child. Every disability comes with a wide range of effects and effective treatments. Not all Downs kids are the same. Or CP kids. Or, in my son’s case, AS (Angelman Syndrome) kids. Just like normal kids, special needs kids have a million subtle and not-so-subtle differences between them and their peers with the same diagnosis. One of those differences, possibly the most important one, is you. How you adjust to this new life will have a huge impact on your beloved child (or adult). Which leads us to:

2 2.You will never totally get this the way you hope. There will be mistakes, tears, fears and moments of doubt and depression. Your old life is basically over, but that’s not necessarily a bad thing. You will find yourself thinking more intentionally about what you can do to enhance your child’s life, which may include getting rid of a lot of old, bad habits and distractions that needed dealt with anyway. One of the greatest gifts of this quarter century of raising my son has been that it forced me to do some serious soul searching and make some huge changes in how I live my life. With Angelman Syndrome, intellectual development pretty much stops at about eighteen months, so some things never change. Other than physical growth, Danny isn’t much different than he has been his whole life, but I am a completely different—and better—person. And that leads me to:

3 3.I can’t speak for anyone else, but I could not have done this without a deep faith in and dependence on God. If you find that idea foolish, then I suggest you return this book and get your refund now. Because without God, I would not be writing this; I’m not sure I would even be alive. One of the greatest results of this amazing journey so far has been realizing that God not only has a plan for Danny’s disability, but that a significant part of that plan is to lead his dad back to his own heavenly father. My own depression, low self-esteem, relationship addiction and alcohol abuse were as important to God as Danny’s mental and physical limitations. Thanks to God, working through my nonverbal son, I finally found the strength to face my life-long demons.

So here is the story of a mentally challenged young man and his equally imperfect old man, and their journey through strange and wonderful waters.

I never planned on being a father. Having already been through a couple of failed marriages and approaching my fortieth birthday, the dream of parenthood had long faded. Besides, I was too busy trying to make a name for myself as a writer and marketing professional to worry about kids.

Discovering that I was about to become a dad brought a crazy mixture of uncertainty, doubt, fear, dread and all those other wonderful things expectant parents feel. But as the big day approached, I began to warm to the idea.

Very early in the morning on the first day of spring in 1992, my wife and I were suddenly jolted out of our slumber by something which we both felt but at first couldn’t pinpoint. We immediately sat up in bed and looked at each other confused and a bit fearful. I thought I had heard a pop somewhere, and my wife had felt something strange. It only took a few seconds for the sleep to clear and the reality to set in that her water had broken (about a week ahead of schedule), and off we rushed down blessedly traffic-free Dallas freeways to the hospital.

Thanks to some good financial decisions my wife had made prior to our marriage, we were able to afford what our ob-gyn referred to as the “North Dallas delivery.” That meant a beautiful delivery suite, highly trained and attentive nurses, and an epidural applied early enough that the only way we knew my wife was having contractions was by watching the monitor.

The delivery was totally uneventful, which was perfect for me as I was an absolute bundle of sleep-deprived, over-caffeinated jitters. Possibly the happiest moment in my life came around noon that day when the doctor placed Danny in my arms. He was a healthy, happy baby whose fine blonde hair gave him almost an angelic appearance (I’m pretty sure I’m not the first person to think that about their newborn child).

In the beginning, life was beyond good. It was amazing. And exhausting. And frustrating. Danny was unable to nurse properly, which meant his mom had to spend lots of time pumping, and I had the opportunity to fully participate in the 2:00 a.m. feedings. His digestion was poor, leading to lots of crying, colic and long, late-night drives to soothe the beast.

But this new normal was just fine with us. We traded our copy of What to Expect When You’re Expecting for a copy of What to Expect: The First Year and steeled ourselves for the bumpy ride ahead.

We waited anxiously for him to do all those precious things babies do—like learning to crawl, then stand, then walk, and utter those first babbling words. But nothing ever seemed to change. At the six-month checkup, our pediatrician lectured us for raising a tyrant since he wasn’t eating any solid food yet, and demanded that we take control of the situation immediately. We did—we found a new, less condescending pediatrician.

Despite the underlying worries, life during that time was wonderful. Danny was happy, always smiling, laughing and waving his arms. He had an aura about him that just made him glow. He wasn’t difficult, fitting easily into our small home-based publishing and marketing business. I took him to business meetings, church leadership training sessions, occasionally even to my weekly Rotary Club meetings. I was a proud father and he was the perfect companion.

One of my favorite memories (and this happened on several occasions) was being in a supermarket or Walmart and having some lady come over and stare at Danny in his car seat in awe. “What an absolutely beautiful baby,” she would exclaim. Then she would look at me and gush, “He looks just like you!” Yes, good times indeed.

At the nine-month checkup, Danny’s new doctor said she wasn’t sure if he was just a late bloomer or there was something more serious going on, and suggested we visit a children’s hospital in Dallas to do some preliminary genetic testing. The real answer would be much clearer by the twelve-month checkup, she said. And so we waited, and watched.

Danny’s first birthday was a bittersweet celebration of the joy of the first year of his life, and the nagging worries about his lack of development. It was also the beginning of a life-changing journey that would take us far and wide, and run through tens of thousands of dollars in medical bills. The genetic testing ruled many possibilities out, but never gave us the definitive name for what we were facing. That was maddening, because without a name, we couldn’t begin to focus our search for the right medicine or operation or therapy that would fix things. And that was our ultimate goal—to fix this problem and make Danny normal.

The summer of 1993 brought two big changes: our daughter Chrissy was born, and one of the members of our church life group introduced us to a Pennsylvania-based program for brain-injured children—the Institutes for the Achievement of Human Potential.

My wife’s pregnancy with Chrissy had been somewhat difficult, particularly in the final weeks, but the delivery went just fine and we brought home another healthy, beautiful baby. Less than three months later, the four of us packed into our van and headed to Philadelphia to go through an intense, week-long session on fixing our brain-injured child.

On the second day of our trip, we finally got the call from the doctor giving us the answer we had been seeking. The latest genetic testing had confirmed that Danny’s condition was known as Angelman Syndrome, a deletion in the fifteenth chromosome on the maternal side.

We had questioned our pediatrician about the possibility of Danny being an Angelman child after his grandmother had seen an article in a Florida newspaper about a professional baseball player whose daughter had Angelman Syndrome. We were struck by how much this little girl looked like our son and how many of her symptoms mirrored Danny’s.

“Oh no,” the doctor assured us. “I’ve been around Angelman kids and they are much more involved than he is. That’s a pretty dire prognosis, and I think he is much more high-functioning.”

“Involved.” That’s a key word in the special needs world. Let’s just say that while a high degree of involvement is a good thing in a normal child’s life, the opposite is true over here on the handicapped side of the fence. Being highly involved means that your child’s condition affects a large number of basic life functions, such as walking, speech, continence, self-care and self-control.

Put another way, if you have a highly involved child to care for, you are going to be highly involved in meeting his or her most basic needs for as long as you can provide that care. Then you get to pass that responsibility on to someone else.

One of the things I love most about God is that He is faithful to dish out the bad news in manageable doses. I know our physician felt terrible about calling us over the Thanksgiving holiday to deliver the devastating news that Danny’s condition was severe and lifelong, with little hope of a cure. But it couldn’t have come at a better time. We were riding high all the way to Philadelphia with the promise of better, miraculous days ahead. The Institutes had done amazing things in the past with people much more involved than Danny. We believed that God had opened this door, and nothing could staunch our excitement.

Fortunately, this all occurred before the widespread use of the Internet and Wikipedia. Had we been able to read more about this expensive program, we might have had some doubts and possibly chosen not to give it a try.

Maybe. But we were pretty desperate. By this time, Danny was twenty months old and could not crawl, pull up, roll over, or even get up on all-fours. He made his noises, but nothing approaching words or even meaningful sounds.

Then, and now, the medical community took a fairly dim view of the Institutes’ approach to treating brain injuries and lack of development through a rigid program of repetitious activities designed to increase the brain’s functions. “We only use about 10 percent of our brain,” they kept telling us again and again. We can’t fix those parts that were damaged by an injury or just never developed, but we can stimulate other areas of the brain to take over those functions.

The training was intense, stimulating and exhausting—ten hours a day for a week. All these years later, I remember some of it. But mostly I remember the sweet, sad families from all over the world who were there to “fix” their imperfect kids. There was the middle-aged dad from Austin, Texas, whose daughter’s perfect life as cheerleader, college student, gymnast and beautiful person came to an abrupt end at the hands of a drunk driver. Now she lay paralyzed and non-communicative. “I’m going to bring her back,” he told me over afternoon coffee. “I know she’ll never be what she was, but I’m going to bring her back to me.”

There was the Hasidic Jewish couple from Israel—dad with his long beard and ringlet hair, mom with a newborn tucked under her shawl. They had come in hopes of fixing their Down’s Syndrome son. We became brief but fast friends as our van provided a private place for her to nurse her baby.

This was my first encounter with a group of special needs family sojourners. I was touched by their hope and dedication. I was moved by their stories. And, in truth, I found myself giving quiet thanks that I didn’t have their “problem” to face.

At the end of the week, the Institutes gave us a program to carry out when we returned home, taught us how to do the different tasks, sold us several hundred dollars’ worth of equipment and books, made us sign an agreement that we would diligently and honestly follow the prescribed program, and sent us on our way. In the parking lot, the emotions of the week and the enormity of the challenge ahead finally hit me. I cried uncontrollably for nearly an hour. They were the first tears I had shed since Danny was born.