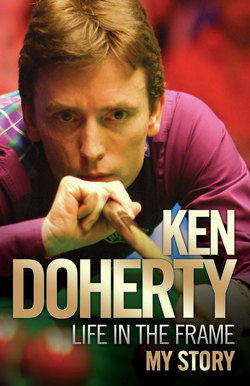

Читать книгу Life in the Frame - Ken Doherty - Страница 5

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеCHAPTER ONE

WORLD CHAMPION

Crucible Theatre, Sheffield, 5 May 1997

To be at the table on the final night of the World Snooker Championship, potting the balls you need to become the winner of our sport’s greatest prize, is every player’s dream.

It had been mine since I was a boy. I’d got into snooker through watching the weekly series Pot Black on television but I realised I wanted to be a professional – wanted to be world champion – when I saw Alex Higgins win his second world title in 1982. I was 12 years old and sat there transfixed. Alex was the most exciting player in the game and had helped to put it on the map through his brilliant play and well-documented off-table antics. I can still see him that night, stood on the stage at the Crucible Theatre in Sheffield after beating Ray Reardon in the final, tears rolling down his face, calling for his wife and baby daughter to join him as he cradled the silver trophy. It was such an incredible, unforgettable moment and I knew as I watched from my front room in Ranelagh, Dublin that I wanted to be part of that world. And there I was, 15 years later, about to follow in Alex’s footsteps.

The odds were stacked against me going into the final. Stephen Hendry was unbeatable at the time. He’d won six world titles, including every single one since 1992. He had established himself as one of the greatest players in the history of the sport and the Crucible was like his back room. For these reasons, most people would have backed him to win but I believed in myself. It was, after all, only a two-horse race. I’d beaten him before and I saw this as my big chance to join the pantheon of snooker legends. I pictured myself lifting the trophy up in that iconic arena, the famous twinkle lights providing the backdrop for a hundred photographs as I held the silverware aloft. I imagined the applause and the acclaim. I had to believe I was capable of experiencing that because if I’d allowed myself to think about Stephen, about how good he was and the damage he could do, then I don’t think I’d have won.

I went into the final full of hope with the feeling that I could come out on top if I played a good tactical match and punished his mistakes. I wasn’t going to out-score Stephen or out-pot him, but I could compete in the safety department and I knew if he missed that I could feed off the crumbs. I got stronger and stronger as the match went on.

I’d led Stephen 15-7 before he won the last two frames of the third session. 15-9 was still a good lead but then he won the first three of the final session and suddenly it was 15-12. Like everyone else in the game, I’d seen him make incredible comebacks before, as when he’d come from 14-8 down to beat Jimmy White 18-14 in the 1992 final, so the pressure was on me. In the 28th frame, I made a break of 61 but he had a chance to steal it. That would have turned the match and made it an unpleasant 15-minute interval for me, spent contemplating defeat having held such a massive lead. However, he missed a red down a cushion and instead of 15-13 it was 16-12. I won the next frame and I was so relieved at that point that I felt great, as if I couldn’t lose.

Potting the last few balls was just surreal. It was like it was happening in slow motion. I looked over to the press seats and saw Tony Drago, a Maltese player and a good pal of mine, with a big smile on his face and that started me smiling. I looked up to my friends in the crowd. I thought of Alex Higgins and my dad, who watched Alex’s 1982 victory with me and who died when I was 13. I just wished he could have been there to see me do it.

Stephen shook my hand and then I was interviewed by David Vine of the BBC before the trophy presentation. I held up the cup just as I’d imagined, only the reality was far better. It was a fantastic feeling.

My family didn’t come over for the final. They couldn’t take the nerves and the pressure. A crew from RTE went round to my mam’s house to film them watching the match but she’d gone out on her bike. She couldn’t even take watching it on the TV. My two brothers, Seamus and Anthony, and my sister, Rosemarie, were there and they had press knocking on the door all day for interviews. They had the champagne on standby but were climbing the walls with nerves.

My mother ended up getting a puncture and had no way of knowing what had happened in the final. She didn’t have a mobile phone and, anyway, she tried to avoid people in case they gave her the latest score. She just wanted to shut the final out until it was over. She had to walk back to the family home in Ranelagh from Donnybrook, pushing her bike all the way, and called in at a friend’s house, which is how she found out I’d won.

My memory of winning the title was made more special by the way the Irish people celebrated with me and by discovering the impact it had had on so many of them. You don’t realise when you’re playing in a big match like that just how many people are living every emotion with you, willing on every pot and going through every little setback. I would discover just what it meant to everyone back home in the next couple of days.

After the final, I did press interviews and then went to the champion’s reception at a hotel in Sheffield. We had a great party. Eamon Dunphy was there and quite a few other friends from Dublin, including the footballer Niall Quinn, who said he’d never experienced tension like it. We partied all night and I didn’t get a wink of sleep. I rolled in at 9am and there was a press conference booked for 10. After that we went down to Ilford in Essex, where I’d been based for almost a decade. It was great to take the trophy down there so that everyone could get pictures with it.

I went home to Ireland on the Wednesday, two days after the final. We landed at a special place in the airport and I was told to let the passengers get off first and stay in the aircraft. Everyone was lined up on the runway: my family, press, airport staff, politicians. It was unbelievable. I came down the steps and my mother was first in line. I gave her a kiss and handed her the trophy.

I’d been in my own little world in Sheffield and didn’t realise just how many people had been watching. I was told that the main police station in Dublin didn’t receive a single call on the final night. Even the criminals had taken the evening off to watch me play Stephen.

I went on Joe Duffy’s RTE show and he had George Best on one line, the boxer Steve Collins on another, footballer Paul McGrath on another and loads of other Irish sports stars who I looked up to and who’d been watching, wanting to congratulate me. It was then that I began to grasp how big a deal this was to Ireland and its people. I hadn’t been aware of that when I was playing, which is just as well because all the excitement would probably have got to me and I wouldn’t have been able to pot a ball.

We had a press conference at the airport and they laid on two buses that went through to the city centre, with me on one holding up the trophy. There were thousands of people lining O’Connell Street. Passing cars beeped their horns and people were leaning out of their office windows, waving and clapping. It was amazing. I felt like some sort of pop star. You see footage of football teams parading through towns and cities and everyone coming out to cheer them, but you don’t think it will ever happen to a snooker player, least of all to you.

We stopped at the Mansion House on Dawson Street. They put on a reception inside and then we got back on the bus and went through to Ranelagh. We stopped again outside Jason’s, the snooker club where I’d started playing, and had a party in there. Then we went to a couple of pubs, the Richard Crosbie Tavern and Russell’s, where parties had been thrown for me. I had Gardai chaperoning me in case things got out of control, which I found strange to say the least. My life seemed to have changed within the space of a couple of days. I didn’t want the guards but they insisted and they were friendly guys, so I sneaked out a Guinness or two for them.

The following weekend the people of Ranelagh threw a street party for me where they put up a bandstand. I got up to make a speech and said I was proud to be world champion, proud to be Irish, proud to be a Dubliner and proud to come from Ranelagh. My mother and I sang Molly Malone and everyone was coming up to me, offering their congratulations, and I could see how genuinely happy they were that this kid they’d known for years had become world snooker champion. It seemed everyone wanted to shake my hand and touch the trophy. I celebrated with old friends from school and complete strangers alike.

Those sorts of scenes could never have been repeated. Even if I’d won it again, it wouldn’t have been as special so I drank it all in. I knew it was something to savour. When people close to you follow your sporting career they have to go through all the disappointments as well as the highs. They feel your pain so it’s wonderful when they can also share in your joy. They’d always believed in me and supported me, even when I hadn’t been doing so well.

I’d had a bad run leading up to the World Championship. Steve Davis hammered me in the Masters at Wembley and also in my home event, the Irish Masters, and then I lost in the first round of the British Open. Ian Doyle, my manager, lambasted me in the newspapers, saying I was lazy and not making enough of an effort to improve my form. Ian was the sort of guy who would use the press like that to motivate his players but what he said shook me up. I felt I’d been doing all the right things but I think his comments focused my mind and made me more determined. I wanted to prove him wrong and show everyone, and most especially myself, that I was capable of being a world class player.

In 17 days at Sheffield I’d gone from feeling low and struggling for form to beating the best player in the world in the biggest tournament of the year. Outside of having children and getting married, there’s no feeling like picking up that trophy. I just wanted to give it a big kiss and hold it up in the air. Nothing as a player will ever beat that moment. The hairs on the back of my neck still stand up when I watch other players win the World Championship and lift up the trophy, as it brings my own personal memories of that special night flooding back.

No matter how many other tournaments you win or other great moments you experience, nothing tops winning the world title. You’d swap all the other tournament wins for one at the Crucible. Your name will always be on the trophy and people will always come up to you with a story of where they were watching or what they were doing when you won it. You’re etched into the history of the sport and to be part of that is very special. That’s why the reaction from the public was so positive, because they recognised what a big deal it was.

I really appreciated the reception I received from the people of Ireland and enjoyed every minute of all the celebrations, but it was also nice to finally come home and just be with my family. I promised my mother that if I ever won the trophy she could keep it on top of the television set and that’s what she did for the next year. She hadn’t wanted me to become a snooker player. She’d felt it was too risky a profession and had wanted me to follow the academic route instead. It was hard for her. She went through all of the emotions with me. I didn’t really understand the extent of that back then but I’ve begun to now that I’ve become a parent myself.

The trophy rarely left the TV set. People would come round just to have their picture taken with it. I paraded it at Old Trafford, Croke Park and Lansdowne Road but it belonged in my mother’s front room. Every day she gave it a kiss and she kept getting it shined up so that it sparkled. I would often come in and have a look at it to check my name was actually on it with all the other great champions.

And it was. It had really happened. I’d really done it: the high point of a career that’s been quite a ride.