Читать книгу Milky Way Railroad - Kenji Miyazawa - Страница 4

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

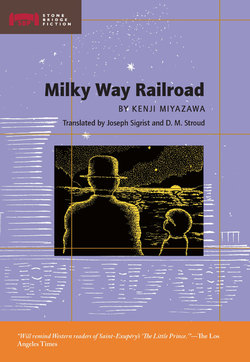

ОглавлениеIntroduction

Kenji Miyazawa (1896–1933) was Japan’s best-loved children’s writer and one of its three greatest modern poets. He spent most of his brief life in the cold, isolated prefecture of Iwate, hundreds of miles north of Tokyo. Although he was well known in literary circles and published in Tokyo magazines, Miyazawa devoted most of his life to teaching school, when he was not engaged as a chemist and government agricultural agent. To while away the long winters, he created stunningly original poems and a series of beautiful tales for children, one of which is translated here.

Miyazawa was well informed about most aspects of modern science, yet he devoted many years roaming from temple to temple in search of the Buddhist doctrine that would best accommodate his syncretic religious beliefs. His fascination with Christianity led him to imagine a kind of universal dogma that would fuse Christianity and Buddhism. He seems to have been particularly taken with the relationship between Esoteric Buddhism and the Hermetic doctrines of Giordano Bruno and Tommaso Campanella, which attempted to reconcile Christianity and Renaissance science with alchemy, astrology, and Eastern esotericism. Bruno and Campanella, in turn, were closely associated with the scientific ideas of Galileo, another great hero of Miyazawa’s.

Milky Way Railroad, probably written in 1927, is a masterpiece of transcendental realism, a children’s science fiction fantasy that expresses in symbolic form many of Miyazawa’s religious and personal beliefs. Its physical setting is the small riverside town of Hanamaki, on the banks of the Kitakami River, where Miyazawa spent most of his life. Hanamaki at that time was connected to the town of Kamaishi by a narrow-gauge railroad, the Iwate Line; the four stations on the galactic railroad in the story correspond to the four actual stops between Hanamaki and Kamaishi.

The time of year is Tanabata, the seventh night of the seventh month, celebrated by the old lunar calendar in August so that it coincides with Obon, the festival of dead souls. The Tanabata Festival was brought to Japan from China in the eighth century. It commemorates the love of two personified stars, both prominent in the summer sky: the Weaver (Vega, in the constellation Lyra, “Harp”) and the Cowherd (Altair, in Aquila, “Eagle”). The Weaver was a princess who wove the garments of the gods. She lived on the east side of the Milky Way and became so devoted to her husband, the Cowherd, who lived to the west, that she began to neglect her weaving. Her father, the Master of Heaven, condemned the couple to be separated, but he allowed them to meet on one night a year, the night of the Milky Way Festival. According to one version of the story, if the princess’s weaving during the year was satisfactory a boatman would come to ferry her across the Milky Way, but in years when her father was displeased he would cause it to rain, making passage by boat impossible. A flock of magpies would then spread their wings to create a bridge across the river. In some parts of Japan, as in Kenji’s town, during the celebration of Tanabata and Obon small gourds are hollowed out, filled with lighted candles, and set adrift on the rivers to symbolize the boat as well as the soul’s passage to heaven.

The two separated “lovers” in Miyazawa’s story are both male. They are two friends and schoolmates, the poverty-stricken Giovanni, whose father, a fisherman, is miles away in Hokkaido, and Campanella, whose father is a professor. On the night of the festival, Campanella, against his will, joins the other boys in their mockery of Giovanni, and Giovanni goes off alone to mope at the top of a hill, where he is suddenly transported on a magical train to the Milky Way. While his friends are celebrating the yearly meeting of the Cowherd and the Weaver, Giovanni will be right up there with the stars. And better yet, he’ll find his friend Campanella on the train with him.

Little does he realize, however, that Campanella has already drowned in the river below and that the train he is on is the train of death. Giovanni is the only one alive and the only one who will return to earth. But for this one night, he is alone with his best friend and nobody will interrupt their reverie. Perhaps Miyazawa was recalling a lost friend of his own or the recent death of his sister, or was describing the relation of the soul and its animus.

It is certain, however, that this story is a kind of Quest. The hero crosses the bridge of dreams after watching his friends sail the lighted gourds representing dead souls on the river below. Then, after climbing a magic mountain, he is given a ticket that takes him to a second river, the Silver River (as the Milky Way is called in Japanese). There he meets the dead souls themselves and visits Heaven. Later he returns over the same bridge and sees the heavenly river reflected in the river below.

This bridge fits nicely into the Japanese literary tradition, for the “Bridge of Dreams” (Yume no Ukihashi) is the title of the last book of the eleventh-century classic The Tale of Genji. But Milky Way Railroad is really a compendium of Eastern and Western myth and folklore. Here we have the scholar who sees the universe in a grain of sand, the bird catcher who is a dead ringer for Mozart’s Papageno, the fields of light, the leaping dolphins (a key Hermetic image that, besides being a symbol of Apollo and the oracle at Delphi, is one of the eight auspicious signs of Mikkyo—Tantric Buddhism—and the derivation of one of the three sacred symbols of imperial rule in Japan, the magatama), the flocks of magpies who form the bridge that unites the Weaver and the Cowherd, the Northern and Southern Crosses, and the golden apples of the Hesperides. Miyazawa’s own original mythmaking is at work in his depictions of the observatory, the lighthouse keeper, and the Pliocene beach.

More than the synthesis of East and West, it is Miyazawa’s attempt to create a literature that fuses the imagery of religion and science that most sets him apart from other writers of his era. Many of his poems are nearly untranslatable, so clotted are they with these fusions of religious and scientific language. But in the purer, simpler vocabulary of Milky Way Railroad, the syncretism is more successful. Indeed, Miyazawa’s playful conceptualizing often seems to anticipate later scientific discoveries. The multiple-mirror telescope in his observatory was not actually built until 1977. Likewise, his galactic Coal Sack suggests a knowledge of black holes that did not emerge until much later, and his speculation about powerful magnetic fields in the Milky Way was replicated by research at the National Science Foundation in 1986.

A devout Buddhist, Miyazawa was often used by the wartime Japanese regime as a posthumous spokesman for their Shinto-based yamato damashi or “persistence in the face of the unbearable.” Miyazawa, however, was delivering a strong message to children in favor of universal brotherhood and compassion. And it is significant for Japanese readers that he began this story in 1927, the year of Ryonosuke Akutagawa’s tragic suicide. Akutagawa, a great writer who was dismayed with the militaristic trends of that time, died with an open Bible by his side and used in his suicide note the words bonyari shita fuan (a vague feeling of uneasiness), which Miyazawa repeats several times in the context of Giovanni’s quest. The same note also contains a reference to the Milky Way.

Yet Miyazawa speaks not just the language of the stars, but also the language of everyday human discourse. And it is the marvelously constructed paradoxes of this tale that lift Milky Way Railroad beyond the level of ordinary children’s literature. Giovanni is sent on an errand to bring milk to his mother, but can’t do it until he returns from the Milky Way. The cow is out of milk just like the one in “Jack and the Beanstalk.” Jack must find his way out of maternal dependence by climbing to heaven, just as Giovanni does as soon as he finds the Pillar of Heaven. This Pillar of Heaven is a reference to the “August Heavenly Pillar” of Japanese mythology, which Izanagi and Izanami must walk around before allowing their Moses-like son to float away in a reed boat.

His best friend, Campanella—representing the Weaver Maiden in the Tanabata legend—falls into the river in which the Milky Way is reflected. Giovanni must go to the Milky Way to find Campanella, but he also finds himself and learns some of the most important lessons of life from examples like the Scorpion, who is transformed into a constellation so he can serve others. Finally, Giovanni, the fatherless boy who yearns for his father’s return, can’t be reunited with his own father until his father’s best friend, the professor, loses a son (Giovanni’s own best friend).

One life ends, another begins. Giovanni has sampled both. As he turns from the gloomy bridge over the Kitakami River, he sees the entire gleaming Milky Way reflected in its waters, the river of earth joined to the river of sky in a perfect bond.

Just as he gave Japanese names to the obviously Western and Christian children on the train, Miyazawa gave his Japanese characters Italian names to emphasize the story’s universality, even though it is set in the very rural part of Japan where he lived. The names are also a tribute to his hero, Tommaso Campanella (1568–1639). Campanella was originally christened “Giovanni,” the name he used until he was fifteen. Thus the two boys, Campanella and Giovanni, are a kind of doppelganger, two aspects of the same child, one poor and reticent, the other rich and better educated. Campanella, who spent twenty-seven years in prison, part of them under torture in a lightless dungeon, wrote a utopian vision of a communist and sexually liberated world order in La cittá del sole (City of the Sun, 1602–23) and was an early champion of Galileo’s scientific proofs that the earth revolved around the sun. He was arrested for leading an unsuccessful revolt against the Spanish conquerors of his native Calabria. Campanella, like Miyazawa, hoped to integrate modern science with both orthodox religion and the mystical concepts that predate both Buddhism and Christianity. There are very slight hints that Miyazawa also favored rebellion: Giovanni’s father may be in jail because of a communist-inspired fishermen’s revolt that was raging at that time in Hokkaido, the topic of a popular novel of the period, Takiji Kobayashi’s The Factory Ship (1929).

Miyazawa, who was an avid opera fan and owned one of the largest record collections in his hometown, probably first became interested in this Italian rebel-philosopher through the 1828 opera Masaniello or La Muette de Portici by Auber and Scribe. One of the most popular operas of its day, whose most famous aria was frequently sung in concerts up to Miyazawa’s time, it described another popular insurrection in the same part of Italy fifty years after Campanella. Miyazawa, in fact, was so impressed that he wrote a poem about Masaniello.

The name of a minor character, Zanelli, also suggests this link to opera and the fictional doubles of the story. Renato Zanelli (1892–1935) was one of the foremost operatic tenors and the most famous Othello of Miyazawa’s day. He traveled and recorded widely, making twenty recordings for Victor in 1919, the year of his Metropolitan debut. Miyazawa would also have been fascinated with the fact that Zanelli switched in mid-career from baritone to tenor and had a brother, Carlo Morelli (1897–1970), who in true doppelganger fashion once appeared as Iago to his Othello in the Verdi opera.

This translation, originally completed by Joseph Sigrist in 1971, was substantially revised by me. It was first published in abridged form by Japan Quarterly in 1984 and subsequently was revised again.

D. M. Stroud