Читать книгу Words of Our Mouth, Meditations of Our Heart - Kenneth Bilby - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеIntroduction

Let the words of our mouth,

And the meditation of our heart,

Be acceptable in thy sight,

O Far I

—Devotional lyric adapted by

Jamaican worshipers from Psalm 19

The half has never been told.” This oft-repeated phrase holds the key to a fundamental Jamaican truth, reminding each generation that no matter how much we think we know, there is always more—much more—to the story. Only with time, patience, and determination can what has long remained hidden be revealed. Nothing in Jamaica embodies this truth better than its music.

The voices and faces in this book speak to this truth from a special vantage point. Not only were these pioneers present when the earliest styles of Jamaican popular music were being born; more important, they themselves were some of the first players and shapers of these styles. Without their creative work, this music, as we know it, quite simply would not exist. Without their portion of the half that remains untold—their memories of the early days and the unique perspectives they can bring—there can be little hope of arriving at a balanced understanding of this music and how it came to be. Their truth is at the heart of this book.

Once scorned and neglected in both its homeland and the Euro-American Capitals of Culture, Jamaica’s popular music has gone on to capture the hearts and minds of people everywhere—and I do mean everywhere. While it is clear enough that this music (and here we must include the distinct genres of ska, rocksteady, and dancehall/ragga along with reggae) has risen to the status of a global art form over the last few decades, it is probably safe to say that no one knows just how vast its actual reach is today. It would take an army of researchers with unlimited time and resources to tally all the local permutations Jamaican music has left in its wake while penetrating virtually every corner of our planet. What we do know is that reggae, like its American cousin hip-hop, has crossed virtually every conceivable border and become one of the world’s most prominent sounds. How could one of the smallest and most economically challenged countries on earth produce a music of such astonishing boundary-breaching power? This in itself remains an enigma—a part, perhaps, of the “half that has never been told.”

Given its remarkable leap from obscurity and disdain to worldwide influence, it is hard to avoid the sense that there is something special and inexplicable about Jamaica’s popular music. What are the actual cultural wellsprings of this music, and who exactly are its creators? Despite the millions of words exchanged about the mysteries of Jamaican music since the global rise of reggae, the readily available answers, in my view, are far from satisfactory. This book is fueled partly by my frustration at this lack of adequate answers to basic questions.

THE NEW SOUNDS of ska, rocksteady, reggae, and dancehall—the distinctive genres of popular music that the world now identifies as Jamaican—came into being primarily in the recording studios of Kingston. On this point there seems to be general agreement. Although the dawn of Jamaica’s recording industry can actually be traced back to the early 1950s, when a handful of cottage enterprises emerged to produce records in the homegrown mento style for limited markets, it was not until the early 1960s that an explosion of recording activity began, unleashing an extraordinary new wave of musical creativity. The birth of Jamaica’s first urban popular music, ska, coincided precisely with the sudden appearance of full-fledged, modern recording facilities in the capital of the newly independent nation, and the major stylistic shifts that followed, from rocksteady through reggae and dub, grew directly out of Kingston’s rapidly evolving studio culture.

The existence of studios depended on certain things. A basic infrastructure was required, including a physical building, recording equipment, and musical instruments. Technicians were needed, including studio designers, recording engineers, and trained maintenance personnel. Some form of centralized economic management was indispensable, as were individual “producers” who possessed (or were able to scrape together) the financial means to initiate and enable recording sessions. None of this would have amounted to anything, however, without proficient musicians—individuals capable of making appealing musical sounds that could be captured on tape and then rendered into marketable products. In a very real sense, these musicians were the most important link in the chain, the foundation upon which everything else stood. They were the primary creators, the producers of first instance. Their livings depended on their ability to come up with novel sounds in the studio that people would want to listen to, dance to, and buy. Because of the demands placed on them, they were the primary architects of new and original musical styles.

This elementary point, you would think, should be self-evident. Yet it has gone largely unrecognized in the voluminous literature on Jamaican popular music. In fact, the fundamental contribution made by these studio musicians remains woefully underacknowledged. This omission can be attributed in part to certain peculiarities that became entrenched early on as the recording of Jamaican music developed into a profitable business. The bosses in this new enterprise were the studio owners and the producers who assembled musicians for sessions and paid for studio time. Session musicians most often were hired on an ad hoc basis, being paid per song or individual recording. Their creative labor was treated as a kind of piecework, the end product of which belonged solely to those who had paid for it. Not only did producers own and control the resulting master tapes, which they were free to convert into marketable commodities as they wished, but they often felt that they owned the music itself in perpetuity. Some even went so far as to claim authorship (or coauthorship), crediting themselves on record labels as composers, and in some cases copyrighting or publishing songs in their own names.

There were, in fact, many more pieces to this puzzle, and students of Jamaican music will be teasing out the complex factors involved in the growth of this somewhat chaotic local music industry for years to come. On the creative side of things, one can single out certain prominent contributors who played an important role alongside the instrumentalists who provided the musical bedrock. These include singers, songwriters, arrangers, and audio engineers. But as more information comes to light about the recording process during the critical formative years, it becomes increasingly apparent that a large majority of the creative work, especially during this early period, fell on the shoulders of the session musicians who ultimately were responsible for inventing the musical frameworks (and with the advent of multitrack recording, the backing tracks and fundamental “riddims”) upon which hit records (and later, dub versions and deejay tracks) were constructed. More often than not, singers arrived in the studio with little more than a sketch of a song, consisting of partial lyrics and a tentative melody devoid of a harmonic progression or arrangement. The musicians routinely supplied the critical missing elements (including the song’s rhythmic structure) on the spot, through a collaborative process of experimentation and playing-in-the-moment—what might be thought of as a kind of spontaneous composition. These session musicians, in effect, actually doubled as co-composers and arrangers.

Seldom did the producer in charge of a session contribute specific musical suggestions to this fast-moving creative process (although there were exceptions). Indeed, producers were often not even present at the actual sessions. For this reason, Jamaica’s foundational session musicians often point out the need to qualify the term “producer.” It would be more accurate, they say, to characterize most of those who bore this title as “executive producers,” meaning simply the parties who financed the production. According to these musicians, those who typically styled themselves “producers” in Jamaica (with rare exceptions, such as the legendary Lee “Scratch” Perry) were producers only in this financial sense and had very little to do with the actual creation of the music they ended up controlling. Creatively speaking, these musicians insist, they themselves were most often their own producers (although they sometimes also credit audio engineers for innovative contributions, which could feed back into the ways session musicians thought about and played their music).

The peculiar way in which the local recording industry was structured led to a perverse outcome. As markets for Jamaican music expanded over time and the economic potential of the music, including older recordings, increased exponentially, the actual creators of the music watched while the “producers”—those who held the master recordings (and sometimes the legal rights)—received most or all of the resulting windfall. Studio musicians were not alone in being deprived of what they saw as their just deserts. Singers (who often were also songwriters) shared this embittering experience, for most of their recordings had been made before the notion of copyright had gained any real traction in Jamaica. As they became aware that recordings featuring their voices (and sometimes songs they had written) were now being sold around the world for profits they would never see, they found that they had little or no legal recourse, since they lacked proper documentation of the circumstances of composition or recording. But the session musicians—the instrumentalists on whose talents the entire enterprise rested—suffered the added indignity of receiving virtually no credit for their efforts. While some singers at least achieved a measure of fame and were able to translate this into new opportunities for live performance and touring abroad, most of the foundational musicians, as times changed and new musical trends took over, were forgotten and languished in obscurity.

Adding insult to injury, many of the first generation of “producers” themselves went on to gain a certain celebrity, eclipsing the musicians who had worked for them. Confronted with a growing variety of Jamaican releases that typically featured prominent “production” credits but little or no information on instrumentalists, fans began to identify particular sonic qualities and stylistic traits with specific studios and producers rather than the revolving “stables” of musicians on whom they depended. “Producers” became as “legendary” for what was thought of as “their” music as for the romanticized stories told about their exploits in Jamaica’s “cutthroat” music business. To a large extent, scholars, music journalists, and other writers have followed suit, treating well-known producers, most of whom were essentially small businessmen looking to turn a quick profit, as if they deserve primary credit for the creative output of the musicians they employed on a temporary basis. Strange as it might seem, the names (or nicknames) of these nonmusician entrepreneurs (for example, Clement “Sir Coxsone” Dodd, Arthur “Duke” Reid, Harry Johnson [“Harry J”], Bunny “Striker” Lee, Vincent “Randy” Chin, Joel Gibson [“Joe Gibbs”], Lloyd “Matador” Daley, Sonia Pottinger, Lawrence Lindo [“Jack Ruby”], Joseph [“Jo Jo”] Hookim, Alvin “G.G.” Ranglin, and Leslie Kong, among others) are today much more likely to be recognized by aficionados of reggae than those of the founding musicians who actually created and performed the sounds that mean so much to so many around the world.

If one chooses to focus on the founding musicians themselves, rather than their employers, the implications are far-reaching. Consider the backgrounds of these foundational players. Although formally trained and highly experienced professional musicians always have played an important role in Jamaican studios—and during the transition from American-style rhythm and blues to ska they were particularly prominent—sessions were, from the beginning, open to anyone who could bring interesting musical ideas and could play with the right “feel.” Over time, as migration from rural areas increased, more and more people from Kingston’s expanding periphery, many of them recently arrived from country parts, turned to the rapidly growing music industry as a means of subsistence. Although few in Jamaica could afford a formal education in music, life across the island was full of music of a noncommoditized kind—music that formed part of the fabric of daily life—and some of those who had participated in such “traditional” musical settings in the countryside or on the urban fringe might well think of themselves as bearers of “natural” musical gifts. As it turned out, more than a few such individuals were able to work up the courage to try their hands in the studios, and before long they were to become a critical part of the mix that produced Jamaica’s distinctive popular sound.

Whether urban or rural, trained or untrained, session musicians are key to the understanding of how this popular music evolved. As a vernacular tradition, a genuine “people’s music,” reggae (in its broadest sense) has always been viewed by the society from which it sprang as an expression of something greater than individual creativity (although individual artistry is certainly appreciated in Jamaica). Like all popular musics, its success, artistic as well as commercial, depended on broad appeal. As the business of Jamaican popular music grew, the participants in the best position to coax forth new sounds that would appeal to the broadest possible cross-section of the population were not those who happened to be skilled in the arts of promotion and marketing, but rather those who, at a profound level, shared a preexisting musical language with the majority of their countrymen and were capable, in the contrived setting of the studio, of translating this effectively into fresh and original, yet locally rooted, syntheses. Rather than the “producers” who provided them with material incentives, or the mobile sound systems that made their recordings available to the masses and became a crucial part of the feedback loop on which they depended, it was Jamaica’s hard-working session musicians themselves who represented the primary creative interface between Jamaican popular music and the Jamaican people.

PERSONAL AS WELL AS professional predilections lie behind this book. Jamaican sounds have been with me from as far back as I can remember. My maternal grandmother lived a good portion of her life on the island. After growing up in Kingston as a young child in the early 1900s and then moving to the United States, she returned to spend much of her adult life in the northern parish of St. Ann between the 1940s and 1970s. She had a keen ear and an artist’s eye, and Jamaica’s physical beauty and cultural richness had much to do with her choice to take up residence there once again as an adult. My mother, in turn, absorbed Caribbean rhythmic and melodic sensibilities in her youth while visiting my grandmother in Jamaica, and also while participating as an amateur musician and composer in the North American vogue for calypso music during the 1940s and 1950s. One of my fondest early memories is that of romping on my hands and knees underneath my mother’s baby grand piano to the magical outpouring of Caribbean-derived rhythms overhead.

My first trip to Jamaica occurred when I was too young to remember anything. But musical memories from later in my childhood have stayed with me. I can remember the strains of mento played by string bands at tourist spots in and around Kingston, the fifing and drumming of Jonkonnu troupes parading outdoors over the Christmas holidays, and the barely audible pulse of unseen drums wafting across the jasmine-laced night air of the St. Ann hills. At a tender age, I began to associate these sounds with the sensory wonders of the environment in which I encountered them—the amazingly lush landscape, the profusion of powerful fragrances, the vibrant colors, the narrow streets bustling with unfamiliar cadences of speech and movement, and the incredible brilliance of the Caribbean moon. While still a young child, I learned from concerned Jamaicans to be aware of duppies, or ghosts, which, I was told, inhabited the tangled roots of cotton trees but also wandered about at night and could become troublesome and dangerous if encountered under the wrong circumstances. I came to feel that the entire place was pervaded by spirits, especially at night, and all the music I heard in Jamaica as a child—even some of the more familiar American tunes coming out of radios—somehow came to be imbued with a peculiarly Jamaican spiritual charge. Though only a visitor, and though my contacts with Jamaicans were mostly superficial, it was hard at this impressionable age not to come under the spell of the island.

Later still, on visits to my grandmother as a young teenager, I remember being intrigued by the rumbling bass and pumping accents of rocksteady and early reggae while passing sound systems on the streets of St. Ann’s Bay, scarcely aware that I was witnessing the birth of a major new form of music. I remember late one night, toward the end of the 1960s, happening upon a Jamaican band playing on a small stage for a local crowd of dancers at a rough-edged nightspot in Ocho Rios. As potent as the vaguely familiar beat was, I was too fixed on the countercultural energy of the rock explosion then dominating the U.S. airwaves to pay more than passing attention. I remember another time, at age sixteen, accompanying a group of friends on a trip into the hills of St. Ann to sample the wisdom of some dreadlocked Rastafarian brethren; the local music that was a conspicuous part of the backdrop made only a vague impression at the time. It wasn’t that I was completely oblivious to the signs at every turn that some new cultural energy was bubbling up in Jamaica. But music had always been everywhere in Jamaica, and people seemed to take it for granted. I took it for granted too.

In the 1970s, when I entered college and began to study ethnomusicology, it seemed only natural for me to gravitate back to Jamaica. The island’s first film of note, The Harder They Come, starring Jimmy Cliff, had recently become a cult hit in the United States, and Bob Marley’s star was on the rise as well. Under Prime Minister Michael Manley, Jamaica had become a major force in progressive Third World politics, and the country’s burgeoning popular music scene had much to do with its sudden entry onto the world stage. Having continued to visit my grandmother in Jamaica into the new decade, I had witnessed some of this from close up. Yet, as inspiring as these new trends in music and politics were, I was drawn at first not to the rapidly shifting soundscape of urban Jamaica but to the older musical traditions of the countryside that resonated with memories from my childhood.

So, unlike most foreigners discovering Jamaica’s music, I focused at first on the “traditional” (the “roots”), leaving the “popular” (the “branches”) for later. Even then, I realized that the conventional partitioning of these imagined domains into separate worlds was not to be given too much credence in the Jamaican context. While working in rural Jamaica as a budding ethnomusicologist and participating as often as possible in traditional musical events, I also spent a fair amount of time in record shops sampling the latest reggae tunes and went to my share of booming all-night sound system dances for the pure pleasure of it. These popular musical sites were among the hot spots of an emerging youth-oriented “roots” culture for which a newfound Rastafari consciousness was the main catalyst. One of the fruits of this youth culture was the newly ascendant genre that later was to become known to the world outside Jamaica as “roots reggae.” In those days, young “knotty dreads” in the cultural vanguard would greet one another on the streets of the city with the slogan, “Roots!” The entire society seemed to be turning “forward,” as Rastas would say, through a redemptive appeal to Jamaica’s African past.

Coexisting with this vibrant youth culture was a still vital older musical world, harboring “folk” forms tied to various traditional social settings that remained a part of daily life—village churches, social dances, wakes, parades, healing ceremonies, communal labor. These too were “roots” musics, although in a much less self-conscious way. And although, at the time, these so-called folk musics were spurned by many urbanizing youths, who saw them as old-fashioned, all of Jamaica’s musics seemed to me to be interconnected, part of the same larger world. The rural quadrille and mento musicians I recorded in the hills of St. Ann in 1975 all knew Bob Marley personally—he had grown up in a neighboring village listening to the very music they still played virtually every weekend—and there was much excitement about the ambitious local boy, a true son of the soil just like them, who was just then starting to take the world by storm. As I continued to move between different parts of Jamaica, exploring its complex and layered social and cultural reality, I began to feel and hear more clearly how much of the old continued to live in the new.

By the time I finally felt ready to turn my focus to the sound of the city and to seek out some of its creators, more than two decades had passed. In the interim I had gained an abundance of experience in the Jamaican countryside. After spending roughly a year in a Maroon town in the mountains of the eastern part of the island, where I had shared in daily life and learned as much as I could about the unique music of that community, I had returned to Jamaica many times to explore other kinds of music, traveling widely and eventually making field recordings of traditional genres in every parish. I had learned the rudiments of Kumina drumming and had sat in on the bandu drum at ceremonies for the Kongo ancestors. I had been welcomed to Revival Zion and Poco meetings and Pentecostal services. I had learned old songs from mediums possessed by the spirits of long-departed African Bongo men. I had added my voice to the chorus at nine nights (wakes) and had joined in on guitar at quadrille dances and mento sessions. I had faced the fire at Rastafarian Nyabinghi ceremonies. I felt prepared, at last, to approach with both confidence and humility those pioneering studio musicians who years earlier had succeeded in synthesizing their varied Jamaican experiences and broader influences into a new music for their country and, as it turned out, the world.

THE WORDS AND IMAGES gathered in the following pages reflect my quest to better understand and pay respect to the flesh-and-blood musicians who, during the twentieth century in Jamaica, performed their own version of what the Haitian anthropologist Michel-Rolph Trouillot called “the miracle of creolization.” Starting with what seemed to be little or nothing, they came up with more than anyone can say, literally changing the soundscape of the world. I wanted to know their own thoughts on this miracle. To my mind, the only way to approach this question was through face-to-face dialogue.

The opportunity to turn this dream into a reality came with a Guggenheim Fellowship in 2004, which provided me with the necessary support over the following year and beyond to track down a sizeable proportion of these foundational musicians in person, in the hope of engaging them in conversations of substance. In creating a list of musicians to contact, I relied on performers or other figures in the world of Jamaican music whom I had already met, the scant references to studio musicians in existing publications, and my own intuitions derived from years of listening and paying close attention to Jamaican popular music. As interviewing got under way, I also asked the interviewees to suggest other important musicians who might not yet have made it onto my list.

What constitutes a “musician” in this context is not always easily definable. I was interested first and foremost in instrumentalists who had been active in Jamaican studios during the critical years of the 1950s, 1960s, and 1970s. However, certain individuals identified primarily as singers also made significant contributions as occasional or regular instrumentalists, while some known mostly for their instrumental contributions also recorded from time to time as singers. Moreover, instrumentalists and singers also occasionally doubled as producers, and the opposite could also occur (though less often)—a person known mostly as a producer might perform in an instrumental or vocal role. In keeping with this fluidity, this book includes both instrumentalists and singers, as well as a handful of exceptional producers who are widely acknowledged for the creative ideas they brought to the studio. However, by choice, I have featured a preponderance of instrumentalists. Also appearing are a smaller but still substantial number of recording artists who worked almost entirely as singers. Among these singers are some who never played any instruments in recording sessions. The individuals in the latter category were included because they were credited by many of the musicians interviewed as important songwriters or arrangers, or because I was aware that they had played prominent roles of various other kinds in popular music and had regularly attended and observed studio sessions during critical periods in the music’s development. Finally, to give a sense of the interconnectedness of Jamaican music as a whole, I have included alongside these professional musicians and singers a number of traditional musicians I have recorded and photographed over the years, whose musical and social worlds overlap to varying degrees and in numerous ways with the musical experiences and repertoires of these same session musicians.

Once I had tracked them down, I found that the studio musicians whose images appear here were more than ready to talk. Most were quick to express their frustration at the neglect from which they had suffered and eager to set the record straight by testifying to the way things had really worked in the studios in the old days. Both they and I knew that the credit they deserved was overdue. Beyond our shared wish to correct the record, I wanted to engage these artists in a serious dialogue about the meaning of the new music they had fashioned in the studios. In their view, where did it really come from? What were their earliest musical experiences, and what kinds of music were they exposed to while growing up? What were they thinking while bringing new forms of music into being in the studios? What about their music mattered most to them? In interviews that lasted between one and four hours, I tried to elicit (or simply keep pace with) their memories and thoughts on the creative “miracle” to which they had contributed, or any other aspect of their careers they deemed especially important.

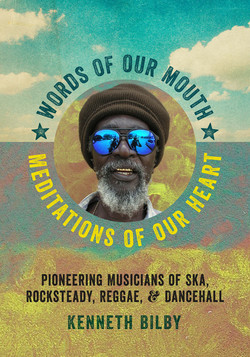

MOST OF THE PHOTOGRAPHS that appear in this book were taken immediately after the interviews from which the juxtaposed texts were extracted. When I look at them, they speak to me of the palpable conviction running through these musicians’ words. Most represent self-posed portraits taken on the spur of the moment—though, as I see it, these were special moments produced by the mutually satisfying exchange of thoughts that had come before.

Of course, only a tiny fraction of what these musicians discussed with me can be reproduced here. In selecting verbatim passages to go with the photographs, I aimed for what seemed to me high points—statements delivered with particular passion and personal conviction. The points made in these passages recur in many of the interviews and would seem to reflect widely held views among Jamaica’s foundational studio musicians. Here I weave these brief individual statements together in a particular order calculated to create a kind of larger conversation that tacks between interconnecting points along a continuum of shared memories and understandings.

The texts accompanying the photographs in this book represent excerpts from interviews I myself conducted (or in some cases, songs I recorded in traditional contexts). All texts are verbatim (except for the bracketed passages), though they have been edited to make them more readable. The texts are in Jamaican English, but many of them also incorporate, to varying degrees, elements from Patwa (Jamaican Creole). I have borrowed a variety of nonstandard spellings commonly used by Jamaican “dialect” writers to indicate differences from “standard” (or metropolitan) English speech.

Each interview excerpt is supplemented with two additional features intended to provide the reader with a bit of background on the interviewee: 1) examples of what I call “standout tracks,” and 2) a capsule summary containing very basic biographical information.

The “standout tracks” represent examples of recordings on which the interviewee played, sang, or otherwise performed, and which I see as somehow special. I limited myself to two such tracks per interviewee. (“Standout tracks” are provided for traditional musicians only in the rare instances in which they are known to have ventured into a studio and made recordings that were released at some point.) The criteria for selection varied, and sometimes were purely subjective. Some tracks were major hits. Some contain original versions of what were to become perennial “riddims” (backing tracks used for many later versions). Some exemplify innovative trends or critical stylistic shifts. Some were pointed out to me by interviewees as recordings of which they themselves were particularly proud. And some I selected simply because they appeal to me personally. In no way should any of them be taken to be the “best” tracks in the career of the individual in question.

The very idea of representing each of these amazingly prolific musicians and singers with only two examples might seem absurd. (Most of the musicians included in this book, even those who have received the least attention for their contributions, have played on hundreds or thousands of recordings; by some estimates, the team of Sly Dunbar and Robbie Shakespeare, to take two musicians who have achieved fame, have played on or produced over two hundred thousand records.) If you have listened to a good amount of Jamaican music, chances are that you have already heard most or all of the session musicians featured in this book. In fact, since studio sessions in the early days were so poorly documented, it is often impossible to tell with certainty who the individual musicians are on a particular recording. The “standout tracks” listed in the following pages, for which the contributing musicians have been identified with a high degree of certainty, are intended simply as pointers. Listeners already familiar with Jamaican music are likely to recognize many of these recordings from the titles; others may use them as a starting point to explore further the individual contributions of these originators of Jamaican music. Careful Internet searches by name of even the least-heralded session musicians appearing in this book will quickly reveal some additional tracks on which they are known to have played, and I encourage readers to use this method to seek out their work. (For additional listening suggestions, see the appendix titled “Recommended Listening” near the end of the book.)

Each capsule summary provides a few lines of background information. When known, the following information (except in the case of a few of the traditional musicians) is presented: instrument(s) (including voice) for which the individual is (or was) known; year of birth (and if applicable, death); period during which he or she first became active in recording or professional performing (or in the case of nonprofessional musicians, in performing in traditional musical events); recording or performing groups of which he or she was at some point a member (not an exhaustive listing); and general musical roles for which he or she was known (e.g., session musician, lead singer, harmony singer, producer). These brief capsule summaries are intended to help the reader quickly fit these important contributors, many of whom have unjustly been consigned to anonymity, into the larger picture of Jamaican music.

As we follow the flow of ideas, some of which appear and reappear in various guises throughout the book, we become privy to what these musicians see as the true sources and key properties of their music. Music, we learn, is for them an important conduit to an unwritten past, a means of communion with the ancestors. It is a carrier of spiritual power, a container of “magic” (as guitarist and singer Bobby Aitken puts it, music is itself a spirit). Music is something from deep within, something “inborn” and “in the blood” (as drummer Horsemouth Wallace puts it, something first experienced in the womb)—something that can suddenly and spontaneously “come out” of people when the time is right. Music is fundamentally a matter of “feel” (intuition and sensation); and because it relies so heavily on intuition, it offers a natural platform for experimental and creative impulses. Music is also fundamentally about “feeling” (emotion); and when feelings are painful, it becomes a healing balm. Music functions in the material world as a crucial means of economic survival, yet is fundamentally about love for one’s fellow human beings and a sense of community rather than commerce. Music serves as a barometer of human suffering and a measure of social conscience that remains ever sensitive to the enormity of Jamaica’s founding sin—the enslavement and attempted dehumanization of an entire people—and its painful echoes in the present. It is a privileged vehicle for messages of all kinds, a powerful voice of and for the people. It is a bearer of warnings and prophecy. It is a cry for freedom and social justice. And, we learn, music is much more than all of this. It is, when all is said and done, an irreducible and essential part of the flow of life in Jamaica. When we view it with a wide-angle lens that takes in the broad array of music makers and genres brought together in this volume, we see that the old and the new, the rural and the urban, the “traditional” and the “popular,” are all integral to this irrepressible flow.

IF THERE IS TO BE a last word in this book, it belongs to the musicians, the original crafters and performers of sounds that, transformed but still recognizable, now circulate around the globe. But, as these musicians themselves might remind us, there is always more to a story than any single telling, or series of tellings, can capture. Some seeking to explain the “miracle” of Jamaican popular music might choose to focus not on the session musicians, but on the ingenuity of the studio engineers who interacted with and influenced the playing of these musicians; at a later point, these engineers took the raw materials created by the musicians and enhanced them with ideas of their own, eventually conjuring entirely new sonic worlds and musical aesthetics through the creation of electronically manipulated “dub” mixes, and in the digital dancehall era, radical new configurations of synthesized sounds. Others might wish to highlight the contributions of the crews who developed the complex and innovative sound system culture that has helped to spread Jamaican music around the world, or the vocalizing deejays who have added yet another tremendously influential dimension by regenerating the verbal artistry that has long been a prominent part of Jamaica’s vigorous oral culture in the new context of mass-mediated performances. One could even argue for the critical importance of the creative entrepreneurship and risk taking of the “producers,” without whom, after all, the enterprise could not have gotten off the ground either; some of these energetic businessmen also helped to shape their “products” in important ways, at times deciding what to record, how to record it, and what to release. All of these parties—sometimes in overlapping roles—played their parts. Creativity, after all, is not exclusive to “artists” (which, in Jamaican musical parlance, most often refers to singers) or “musicians” (players of instruments). But, in the written history of Jamaican popular music, the musicians remain, paradoxically and regrettably, the most unsung of all.

There are yet other portions of the proverbial half that has never been told that cannot be given equal time here, though these too are deserving of attention. Although the testimonies in this book occasionally point to sources of musical inspiration from beyond Jamaica, the primary focus stays on local roots and concerns. Once again, this is because I selected passages in which points were made emphatically; and these musicians tended to become particularly animated and to speak with special conviction when discussing ways in which they felt their music was specifically Jamaican. Yet Jamaica has never been closed to the rest of the world. If one were to draw on other interviews (or indeed, other sections of those excerpted in this book), it would be possible to construct a view rather different from what is presented here—one oriented more toward North American or other foreign influences than indigenous sources. This view has value as well. Make no mistake: Jamaica’s session musicians always have been cosmopolitan in spirit, open to the wider world and ready to take from it as needed. And they have continued to look outward. Indeed, whether for artistic or economic reasons, many of them have become world travelers. To get a good sense of this, one need only consider how far I myself had to journey to find some of them. This project brought me not just to Jamaica, but also to London, Birmingham, New York, Miami, Boston, Philadelphia, Washington, D.C., Chicago, Los Angeles, San Francisco, Toronto, Montreal, and elsewhere.

But sometimes it is necessary, when searching for answers, to go back to where it all started. In this case, that is where an essential part of the half that remains to be told can still be found. And many of the thousands of non-Jamaican singers and players of instruments who have carried the flame of Jamaican music around the world, I think, would agree. For no matter how much they have done to make this music their own, lending their own words and giving their own hearts to it, something crucial remains of its original spark—something without which their own creations would be diminished. In much the same way, without the words and the meditations of the actual originators of Jamaican music, our understanding and appreciation of what has become one of the world’s most influential musics would be greatly diminished. By listening to the originators, whose words and images grace these pages, and by remembering the inestimable portion they contributed, we help to keep the flame they long ago ignited burning bright.