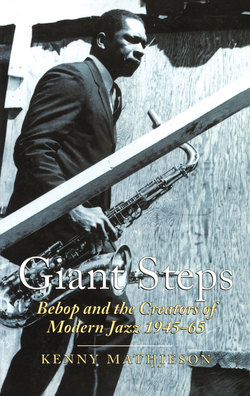

Читать книгу Giant Steps - Kenny Mathieson - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеCharlie Parker

Charlie Parker is the ultimate example of both the creative glory of bebop as a musical form, and the degrading destructiveness of its social ethos. Bebop cemented the domination of the soloist in jazz begun by Louis Armstrong two decades earlier, and nobody stood higher on that pinnacle than Parker. A largely self-taught musician, a drug addict and chronic drinker with acute self-destructive tendencies, Parker and his music burned as brightly as any in the annals of twentieth-century culture, but, unlike the more astute Dizzy Gillespie, he was never destined for longevity.

Burned out by drugs, alcohol, and the pressures of trying to maintain his own slipping artistic standards, he died on 12 March 1955 while watching Tommy Dorsey’s television show in the Manhattan apartment of Baroness Pannonica de Koenigswarter (generally known as Nica), a rebellious member of the Rothschild family who became a celebrated patroness of jazzmen – Thelonious Monk spent his last years in her New Jersey home, and also passed away there.

Parker’s life and death is the stuff of legend, and the sequence has been played out many times in American music, from Hank Williams and Elvis Presley to Jimi Hendrix and Marvin Gaye. The physician who performed the final inspection of the corpse infamously estimated his age to be fifty-three. He was thirty-four. Nica claims to have heard a momentous rumble of thunder at the moment his pulse finally faltered and stopped. Alternative unsubstantiated accounts of his death have circulated, suggesting he was killed by another musician – one story suggests internal injuries received in a fight, another that he was shot. The graffiti began to appear in the streets of Greenwich Village almost immediately, with its simultaneously defiant and triumphant cry: Bird Lives!

And so he does, or at least his music does, both in itself and in the huge, pervasive influence which it exerted on the course of modern jazz. There has also been more than one account of the origins of his nickname, but the most canonical version maintains that he acquired it while with the Jay McShann Band, after ordering the driver to go back and let him retrieve a chicken (or ‘yardbird’) hit by the car they were travelling in, to be cooked and eaten at their destination because black musicians travelling in the south generally roomed in private houses, since hotels were rigorously segregated, and most towns offered no alternative. The other musicians began to call him Yardbird, which was sometimes shortened to Yard (Dizzy Gillespie’s favoured version), but most commonly simply to Bird. Its connotations of freedom and flight have been milked relentlessly by writers and album-compilers ever since, but with ample justification.

Ross Russell first became involved with Parker as the co-owner and sole record producer of Dial Records in Los Angeles, a shop-based label which cut some of the saxophonist’s most important sides. His biography of Parker, Bird Lives!: The High Life and Hard Times of Charlie ‘Yardbird’ Parker, remains the most vivid account of his life, despite its self-serving tendency to myth-making and the liberties it takes in reconstructing many events. (Carl Woideck’s Charlie Parker: His Music and Life, is largely a penetrating analysis of Bird’s music, but also attempts to sort out some of the biographical confusions surrounding the saxophonist in a useful opening chapter.) Here Russell describes Parker’s attitude and reaction to drugs.

Charlie’s attitude was conditioned by the discovery that his physiology, uniquely resilient in so many ways, could tolerate heroin far better than most. Junkies were usually detached and on the nod. They had no appetite for food, and less for sex. They shunned alcohol as if it were poison. Charlie experienced none of these reactions. His appetites went unchecked. He could drink and he could eat like a horse and run after all the women that interested him. At Monroe’s, where the management stood drinks, he would start the night with two double whiskeys, and continue to down shots between sets. Nor was there ever a time when he could not play.

That final statement seems an extraordinary one, and if accurate, certainly only applied for a limited time early in Parker’s use of heroin, for Russell’s own book, as well as many others, goes on to catalogue a whole series of occasions when the saxophonist could not play. He became infamous for missing sets and entire gigs, and for nodding off on stage. Gil Fuller’s story of his brief sojourn in Dizzy’s big band in the previous chapter is only one of many such tales – Norman Granz once offered Red Rodney a substantial bonus for every time he delivered Bird on time and in fit state for their portion of a JATP touring show: the trumpeter never collected once. It is true that Parker’s physical and carnal appetites certainly remained prodigious, and he does seem to have had a high tolerance of narcotics, but that combination of hard drugs and hard drinking killed him well before his time. Russell, though, has more to say on the subject.

Drugs allayed the pressure he suffered from the lack of steady work, the public indifference to his music, his contradictory, indeed ridiculous role – a creative artist composing and improvising in a night club. Drugs screened off the greasy spoon restaurants and cheap rooming houses with their unswept stairs and malodorous hall toilets. Drugs kept him out of the military draft: an army psychiatrist had taken one look at the needle marks on his arm and immediately classified him as 4-F. Heroin became his staff of life. The monkey on his back kept the outside world off it. Like all who meddled with drugs, Charlie believed that he could kick the habit at his own convenience. He experimented with goof balls (phenobarbital) to decelerate the highs and alleviate withdrawal symptoms. The score became the most urgent task of each day. He learned the trick of borrowing small amounts of money, a dollar or two, sums too small to be remembered. His lifestyle was hardening into a mold he would never succeed in breaking. Except for a single factor, there was nothing to distinguish Charlie from hundreds of other Negro youths who had been drawn to New York City and were drifting aimlessly about the streets of Harlem, in imminent danger of being swallowed by the underworld. That factor was the saxophone.

The pressures of living and creating in a society where both your art and your humanity are devalued by your skin colour was emphasised for Parker by his experiences of Europe in 1949 and 1950. Like many black musicians, he found a more respectful environment for his music and his person there than in his homeland, and did not encounter the kind of routine racism, both implicit and overt, which was the everyday fabric of life back home. However, Angelo Ascagni, who met Bird through Dean Benedetti, is quoted in Robert Reisner’s Bird: The Legend of Charlie Parker as saying that the saxophonist did not succumb as much as he is reputed to have done to the welcome, but rather saw ‘a sort of subtle prejudice’ at work in the European attitude, and refused to fit himself into ‘the mold of an African genius, an uninhibited primitive spirit, or any of the idolizations which the European opposes to the American abuse of the Negro’. Reisner’s collection of reminiscences was the first book on Bird, and has been a source of a great many much-repeated quotes, but the unreliability of oral testimony, and the great number of contradictory statements in it, make it a dubious witness at best, and readers should take that ‘legend’ in the title literally.

Nonetheless, some jazz historians, led by the redoubtable James Lincoln Collier (see, for example, his provocative essays in Jazz: The American Theme Song) and Gene Lees, have attempted to argue that our view of such matters has become distorted. While it would be foolish to pretend that racism was purely an American phenomenon, or love and respect for jazz uniquely European, generations of jazz musicians have provided overwhelming subjective evidence to back up the point.

Of course, the use of narcotics in music was never limited to black musicians – indeed, the classic account of that subject comes from the white saxophonist Art Pepper in his harrowing autobiography, Straight Life. If they were shielded from some of the worst consequences of casual and institutional racism, however, the low regard in which jazz – and especially the new jazz – was held rubbed off on white as well as black artists, and they occupied the same bandstands in the seedy club-land underworld, with its ongoing ugly parade of pushers, pimps, gangsters and conmen. Pepper not only chronicles his drug use, but also the effects of reverse racism, the so-called ‘Crow Jim’ principle in which white jazz musicians were designated second-class citizens, not only by society at large but by some of their fellow black musicians, who saw them as interlopers on a black art form.

Nor can all responsibility rest with the world through which the saxophonist moved. Others – and Dizzy is a notable example – succeeded far better in combating the perils of the jazz life as it existed at that time, and some – possibly much – of the stimulus for Bird’s all too willing slide into addiction has to be rooted in his own personality. Whatever the combination of inner weakness and outer temptation, private demons and public devils, it proved a lethal one in the end, and drove one of the great musical geniuses of the twentieth century to a tragically early demise.

Astonishingly, despite constant police harassment, he was apparently only arrested once for possession, when he received a three-month suspended sentence in 1951, leading to the loss of his cabaret card, a statistic which says a great deal for his astuteness and street-cunning. His use of drugs inevitably left many other musicians, black and white, facing the burning question: to play like Bird, do I have to turn on like Bird? Did that little spoonful of white powder hold the keys to the kingdom of improvisational greatness? The answer seems obvious: no, it did not, and Bird always said the same thing. His argument – essentially ‘do as I say, not as I do’ – lacked conviction in the eyes of those under his powerful spell, and a long line of jazzmen turned on to heroin on the back of his example. Even more, however, were inspired by his musical example. Perhaps more than any other single figure in the history of jazz, Parker’s influence was all-pervasive, affecting not just alto saxophonists, or even saxophonists in general, but players on every instrument. After Bird, there was only one flight-path to follow.

Charles Parker, Jr was born in Kansas City on 29 August 1920, on the Kansas side of the Kaw River which divides that state’s portion of the city from the Missouri one. By the time he started to develop a serious interest in music, the Missouri side of the city (where the family now lived) was reaching its peak as one of the crucial musical centres in jazz history. The town was effectively run by the notorious Tom Pendergast, and the wholesale corruption of his regime had encouraged a thriving hotbed of rackets – gambling, prostitution, extortion, narcotics – all carried on largely untroubled by the police, who kept out of the way other than to collect their pay-offs. As in other cities, the gangster-run clubs provided a dubious working environment for musicians, but the dingy drinking dens which sprang up around the city’s Twelfth Street also provided the well-springs of the Kansas City sound. The legendary jazz sessions would carry on through the night, and occasionally round the clock. Clubs like the Harlem, the Hey-Hey and the Reno attracted the best musicians of the day, who either took up residence in KC – the New Jersey-born Count Basie ran the city’s number one band – or sat in on the jam sessions when passing through on road tours with nationally known outfits like the Duke Ellington or Cab Calloway orchestras.

According to Russell, and the testimony of Bird’s friends at the time, as a teenager Parker ingratiated himself with local musicians, and they would sneak him into the quiet balcony above the stage at the Reno. There, he would absorb hour after hour of music, and try to apply the sounds he heard to his own battered alto, bought by his hard-working, doting mother and barely playable. Instruments did not seem to matter much to Bird – he got his first decent instrument, a brand new Selmer, with the insurance pay-off following a car accident on the way to a gig in 1936 – but a good horn was useful for its pawn value as much as its sound. Since he replicated his distinctive sonority on a whole succession of borrowed instruments over the years, and played a plastic alto from England for a time in the 1950s with equally positive results, it is reasonable to assume that he regarded tone production as a function of the player rather than the horn.

Like the later sessions at Minton’s and Monroe’s, the Kansas City jam sessions were merciless affairs for anyone who did not have their chops and their musical ideas together. As a tyro musician, Parker endured some famous humiliations, firstly in attempting a double-time passage on ‘Body and Soul’ with some of his peers at the Hi-Hat, and subsequently in an even more humiliating breakdown at the Reno, when he was ‘gonged-off’ by an irate Jo Jones, the great drummer of the Basie band. The flying cymbal provided a tiresomely repeated leitmotif in Clint Eastwood’s well-intentioned film of Parker’s life, Bird (1988), but it also provided the stimulus for further advancement in the altoist’s playing.

A summer spent working with singer George Lee’s band at the summer resort of Lake Taneycomo in the Ozark mountains in 1937 provided an intensive wood-shedding experience which did much to set him on the right course following that humiliating night at the Reno in 1936. Parker had always proved willing to learn everything he could from those around him, and had the capacity to put in endless hours of practice on his horn. He knew nothing about playing in different keys, for example, but when the realisation began to dawn, he did not go out and master the three or four most common keys used in jazz, but learned to play with equally dazzling facility in all twelve. His gradual assimilation of the rudiments of harmony from a succession of informal teachers – pianist Lawrence ‘88’ Keyes, clarinettist Tommy Douglas, altoist Buster ‘Prof’ Smith, guitarist Efferge Ware and pianist Carrie Powell – as well as the long hours spent wearing out recordings studying Lester Young brought about a remarkable metamorphosis in his playing. He began to pick up jobs around town with Buster Smith (an important early influence) and pianist Jay McShann, who described his recollections of first meeting Bird to Ross Russell.

I first ran into Charlie in November or December of 1937 at one of those famous Kansas City jam sessions. Charlie seemed to live for them. I was in a rhythm section one night when this cocky kid pushed his way on stage. He was a teenager, barely seventeen, and looked like a high school kid. He had a tone that cut. Knew his changes. He’d get off on a line of his own and I would think he was headed for trouble, but he was like a cat landing on all four feet. A lot of people couldn’t understand what he was trying to do, but it made sense harmonically and it always swung.

Musical ideas, that is what jam sessions were really about. Charlie was able to hold his own against older men, some of them with years of big-band experience. He was a strange kid, very aggressive and wise. He liked to play practical jokes. And he was always borrowing money, a couple of dollars that you’d never get back. He was trying to act like a grown man. It was hard to believe those stories about what a poor musician he’d been. That fall when he came back from the Ozarks he was ready.

As the decade drew to a close, though, Kansas City was changing. Pendergast had been tumbled (he was tried and convicted of tax evasion, the same charge which had brought down Al Capone in Chicago), and the city had moved into a clean-up phase which destroyed the nightclub scene. The geographical focus on jazz itself was also shifting again. The Count Basie Band had broken out from Kansas to become a nationally-known outfit with their powerful riff-based style (the riff, a pervasive figure in black music, is a short melodic phrase, usually of four or eight bars’ length, either repeated literally or varied to accommodate a harmonic pattern, which formed the cornerstone of the south-western swing style), and the drift of top musicians away from the city – particularly to New York – became a haemorrhage in the wake of their success. Parker, too, had made his initial move out of Kansas when he hopped a ride on a freight train to Chicago in 1938 or, more probably, early in 1939, by which time he was already using heroin. Again, accounts vary on when he actually started using drugs, but the likely year seems to have been 1935. That first scuffling trip subsequently took him to New York, where he worked as a dish-washer at Jimmy’s Chicken Shack in Harlem for three months (the only non-musical job he would ever take). It was grinding, dirty work for poor pay, but his compensation lay in being able to absorb resident pianist Art Tatum’s harmonic genius night after night.

Parker’s style at that point was already showing evidence of the expanded harmonic awareness which would underpin the development of bebop. Exposure to Tatum’s playing (according to Russell, he was never able to pluck up the courage to speak to the blind piano genius when Tatum would slip into the kitchen to take a hit from the bottle of Scotch he kept there) further expanded his harmonic horizons, and in the few opportunities he did get to play, he worked on developing his still inchoate ideas. By his own testimony, the final revelation took place in the back room of an establishment named Dan Wall’s Chili House, where he was practising with guitarist Bill ‘Biddy’ Fleet on one of his favourite improvising vehicles, ‘Cherokee’. The famous ‘quote’ which follows is given as a verbatim one in Shapiro and Hentoff’s Hear Me Talkin to Ya, but is actually a paraphrase of a section of a Down Beat interview from 1949, in which Parker’s direct speech and the words of the writers, Michael Levin and John S. Wilson, have been combined as if it was a direct quotation. As Woideck points out in his study of the saxophonist, ‘the effect is to make the account more vital than the original’, and since no damage is done to the meaning of what Bird was telling the interviewers in the process, we will let it stand in the first person.

I remember one night before Monroe’s I was jamming in a chili house on Seventh Avenue between 139th and 140th. It was December 1939. Now I had been getting bored with the stereotyped changes that were being used at the time, and I kept thinking there’s bound to be something else. I could hear it sometimes, but I couldn’t play it. Well, that night I was working over ‘Cherokee’, and as I did I found that by using the higher intervals of a chord as a melody line and backing them with appropriately related changes, I could play the thing I’d been hearing.

What Parker had discovered was that a new and radically different-sounding melody line could be conjured up through moving away from the obvious melody notes within a given chord sequence, and instead using less familiar notes made up from intervals further away from the chord root. He began to extend his use of the upper intervals, the ninths, elevenths and thirteenths beyond the octave (intervals falling within a given octave are known as simple, and those beyond it as compound), and concentrated on the challenge of not simply using those notes to create a new melody line, which was difficult enough in itself, especially given his highly original rhythmic accentuation and increasingly fit-to-bust tempos, but of making their natural tendency toward dissonant effects (the ‘wrong’ notes which so many musicians of the older school heard in bebop harmony) reach an appropriate resolution within the harmonic fabric of the tune. There are strong hints of that direction in his first studio recordings, made with the Jay McShann Band in 1941, notably in ‘Swingmatism’ and his solo on ‘Hootie’s Blues’, which Russell suggests was ‘a Pandora’s box of things to come’. In his fine study Celebrating Bird: The Triumph of Charlie Parker, Gary Giddins encapsulates those developments at this point in his career.

Parker was achieving the kind of fluency that only the greats can claim: complete authority from the first lick, and the ability to sustain the initial inspiration throughout a solo, so that it has dramatic coherence. His tone became increasingly sure, waxing in volume despite the deliberate lack of vibrato. It was candid and unswerving, and it had a cold blues edge unlike that of any of his predecessors. The musicians in New York had tried to intimidate him into aping the clean, pear-shaped sound of Benny Carter or the rhapsodic richness of Johnny Hodges. His contemporaries in McShann’s band knew what he was after. They were amused, too, by how fast his mind worked, as he imitated sounds echoing in from the streets – engines backfiring, tires, auto horns – and worked them into musical phrases. He not only mastered Tatum’s trick of juxtaposing discursive melodies in such a way that they fit right into the harmonic structure of the song he was playing, but took it another step: he quoted melodies that had lyrical relevance to the moment. He might nod to a woman in blue with a snippet of ‘Alice Blue Gown’, or a woman in red with ‘The Lady In Red’, or comment on a woman headed for the ladies’ room with ‘I Know Where You’re Going’. He had a ripe eye for women.

The full fruition of those ideas was still some way off, however. He remained with McShann until 1942, but chose to stay in New York rather than swing back on another southern tour with the band. He continued to develop both his ideas and his facility in executing them in a way that was entirely new to jazz, playing in the jam sessions at Minton’s and Monroe’s, and in the seminal swing-into-bop transitional big bands of Billy Eckstine and Earl Hines (where he occupied the tenor saxophone chair and is said to have perfected the art of sleeping on stage with his horn in playing position to fool his leader).

A 1944 session with guitarist Tiny Grimes is usually seen as the first of his mature recordings, but it is also something of a preface to the major achievements which were now just around the corner. The session’s two instrumentals, ‘Tiny’s Tempo’ and ‘Red Cross’, both feature cogent contributions from the altoist, and he was back in the studio on several occasions as a sideman in 1945, with pianist Clyde Hart (featuring very odd vocals by the singer Rubberlegs Williams, allegedly under the influence of coffee which Parker had spiked with Benzedrine to liven up a miserable session), the self-styled Sir Charles Thompson on piano, vibraphonist Red Norvo and, most significantly, with Dizzy Gillespie on the crucial sessions of February and May, which produced bebop classics like ‘Groovin’ High’ and ‘Salt Peanuts’. His playing is striking at this stage, but is still a step away from the full unfettered flow of musical discoveries which he would unleash as his phrasing and rhythmic style reached maturity in the exhilarating ferment of the quintet music he was creating with Gillespie at The Three Deuces on 52nd Street. It all came together in the recording studio on 26 November 1945, when Bird cut a session with a quintet which featured both Miles Davis, sounding rather out of his depth, and Dizzy, who played piano as a late stand-in (depending on which source you consult, the scheduled pianist was either Thelonious Monk or Bud Powell). To complicate matters, another pianist, Argonne Thornton (also known as Sadik Hakim) was pulled in to contribute to the session and is heard on ‘Thriving On A Riff’.

Curly Russell and Max Roach provided a real bebop rhythm section for the band, who cut five tracks as well as Parker’s alto exploration on the literal ‘Warming Up a Riff’, which he did not know was being recorded – his outrageous interpolations have Gillespie shouting with laughter towards the end. They included two very different blues tunes in F, ‘Billie’s Bounce’ and ‘Now’s The Time’ (which later became a rhythm and blues dance hit as ‘The Hucklebuck’, although Bird received nothing as composer, which may have been a form of poetic justice since the tune may not have been entirely original with him in the first place – one theory credits it to saxman Rocky Boyd), as well as the riff tune mentioned above and an informally recorded, abruptly terminated ballad based on ‘Embraceable You’ which was given the non-committal title ‘Meandering’ but no matrix number.

The final tune laid down that day is one of the most incendiary slices of jazz ever committed to record. Even now, ‘Koko’ remains an astonishing piece. It is a contrafact of one of his favourites, ‘Cherokee’, and the band actually start into the theme of the tune following the complex introduction in the first, aborted take (Hakim plays piano in the intro here, and it may be he who is heard behind the alto solo on the completed master take). That is quickly dropped, though, probably to extend the alto solo, in the master take, which sizzles along at a ferocious pace (about quarter note = 300). It begins with a highly unusual 32-bar introduction: eight bars of unison chorus, followed by eight bars each of trumpet (played by Gillespie rather than Davis) and then alto, then a final 8-bar section which begins by repeating the unison theme of the opening, then abruptly executes a sharp-angled turn leading into the first solo chorus. The effect is immediately arresting, and a portent of things to come.

Parker then soars into a two chorus, sixty-four-bar solo which quickly became an icon for saxophonists. It is a tremendous outpouring of rhythmic and harmonic ingenuity, and if it was not intended as a clarion call for the new music, it certainly served as one. Parker’s steely tone and the calculating complexity of his invention can seem daunting, but the sheer explosive exuberance of the music remains breathtaking. Max Roach follows his leader with a drum break which maintains the high-strung tension of the piece, and the ensemble fall back into the final flourish of that complex introduction, this time repeated as a triumphant coda. The whole piece has the air of a defiant ultimatum: this is our music, take it or leave it.

Parker always complained about the use of what he saw as the demeaning word ‘bebop’ to describe his music, preferring the naïve option of just calling it music. When it came to naming the works that posterity would view as masterpieces of a serious art form, however, he was as cavalier and careless as any of his contemporaries, and just as guilty of leaving us with a legacy of tune titles which belong in the playroom rather than the conservatory, in direct opposition to the musical polarities they represent.

In the case of ‘Koko’, the designation of this immortal slice of recorded history was left to producer Teddy Reig, who came up with the title (possibly inspired by the alliterative effect in the closing bar) after the fact, thereby fulfilling the saxophonist’s obligation to provide four original tunes for the session, despite the piece’s distant harmonic roots in ‘Cherokee’. (It is not, incidentally, related to the famous ‘Koko’ recorded by the Duke Ellington Orchestra.) That casual indifference was not a one-off, since Reig was left with the job of inventing names for a number of other tunes during his association with Bird (and with other beboppers in the Savoy fold, including Dexter Gordon) – documented examples include ‘Donna Lee’, a Miles tune named after Curly Russell’s daughter, and ‘Cheryl’, a Bird tune from the same session named for Miles’s daughter (see Douglass Parker’s ‘“Donna Lee” and the Ironies of Bebop’ in The Bebop Revolution in Words and Music.

The session again underlines Parker’s reliance on a set pattern of formal structures: the blues, with its twelve-bar choruses and formalised but malleable I-IV-I-V-I chord progression; the harmonic structure of the AABA, thirty-two-bar popular song exemplified by the ‘I Got Rhythm’ changes; and, more distantly, the riff tunes of his south-western roots. These were the foundations of his art, and although what he did within them transcended those origins in spectacular fashion, he eventually grew to feel that his music was artificially constrained by his dependence on too narrow a structural basis. His aspirations to work in more complex modernist compositional forms, which he revealed to the composer Edgar Varèse and others, were never to be fulfilled, and it is hard to know how serious he was about them.

That New York session, like the earlier sessions with Tiny Grimes and those under his own name, was made for one of the most important of the independent labels recording the new jazz. Savoy was founded in 1942 by a traditional jazz fan named Herman Lubinsky, and its most successful releases were in the swing and blues fields. The stimulus to bring the modernists on board came from producer Teddy Reig, who arranged important pioneering recording sessions not only with Parker, but with Dexter Gordon, Fats Navarro, J.J. Johnson, Sonny Stitt (in a band which featured Bud Powell), Miles Davis and Serge Chaloff, among others. The label continued to record some jazz in the 1950s and 1960s (including free jazz sessions with the likes of Sun Ra and Archie Shepp), and their work has been extensively re-issued in various forms.

Next came one of the most troubled episodes of Parker’s life, and one which took him away from the city for well over a year at a crucial time in the development of the music. In December of 1945, the Dizzy Gillespie All-Stars were booked into a six-week engagement at Billy Berg’s nightclub in Los Angeles, the first time that a New York-based bebop outfit had been scheduled to appear on the west coast. Knowing Bird’s already well-established reputation for unreliability, Dizzy and promoter Billy Shaw hired Milt Jackson as an extra member of the band who could fill in when the saxman did not make the gig. As it turned out, they also added the underrated tenor saxophonist Lucky Thompson once they reached LA, and he replaced Parker with increasing regularity as the run went on.

The portents were ominous right from the start. During a much-delayed train journey to the coast, Bird, suffering from withdrawal symptoms, wandered off into the desert in the midst of a panic attack and had to be strapped to his bed for the remainder of the trip. He managed to score morphine from a doctor on arrival, and although he missed the first two sets, he eventually made the gig on the opening night at Berg’s on 10 December, an occasion which was, in Ross Russell’s words, ‘a red letter event, its attendance de rigueur for everyone with any claim to status in the west coast jazz community’. The public, though, proved more resistant to the new music, and audiences quickly fell away.

Bird was up and down, ready to sweet-talk his acolytes and go jamming in the jumping after-hours club scene along Central Avenue on the good nights, short-tempered and withdrawn on the bad. The determining factor was, of course, whether or not he had scored – again, as Russell observes, ‘for the first time in his life, heroin had caught up with him’. Ironically, his connection in LA was a man called Emry Byrd, whose more familiar monicker has gone down to posterity through the tune Parker named for him – ‘Moose The Mooche’. From his wheelchair, he ran a shoeshine stand on Central Avenue which fronted for his dealing activities, and Parker became so dependent on his back-door services that he signed an extraordinary document giving Byrd half of his royalties under the exclusive deal he had just signed with Ross Russell’s Dial Records. The dealer was jailed shortly afterwards, and never did collect on his contract.

While at Berg’s, Bird and Dizzy cut some sides with singer and hipster Slim Gaillard, which includes an exchange with Bird on the vexed subject of reeds on ‘Slim’s Jam’. Both men were featured in a poll-winners’ concert at the Philharmonic Auditorium in LA on 28 January 1946, an occasion which was the genesis of Norman Granz’s Jazz at the Philharmonic touring presentations, an attempt to recreate the jam session ambience in a formal concert setting. (Although he quickly found alternative venues to the stuffy and unwelcoming Philharmonic, he retained the prestigious name.) This was the first time that Bird had shared a stage with his hero, Lester Young, although it was a very different Lester from the one he remembered tearing up the Reno a decade before. Bird turned up late from his score and can be heard making his entrance on ‘Sweet Georgia Brown’ just before the interval on Granz’s recording of the date, which now features on the first disc of the ten-CD set Bird: The Complete Charlie Parker on Verve. It also boasts a famous Bird solo on ‘Lady Be Good’ among the five selections, and although the jazzmen were quickly shown the door from that pompously august venue – the owners argued the crowd were too exuberant, but Granz attributed the ban to their dislike of the racially integrated group he put on stage, and his musicians agreed – the concept was now launched and continued as a very successful touring package under the JATP banner for many years.

The notion of taking the jam session onto the concert stage was not entirely new with Granz (Eddie Condon, for example, had organised a series of traditional jazz jam sessions at Town Hall in New York in 1942), but it was JATP which took the idea onto the international stage. Bird would be featured on further recordings in that context in 1949 and 1950, all included in the Verve collection.

As the engagement at Berg’s closed, however, Parker was in a downward spiral. He cashed in the flight ticket provided to get the band back to New York, which Dizzy had unwisely given him, and disappeared, forcing his collaborators to leave him behind on the coast. He scuffled for a while, working at a new bottle club (so-named because customers brought their own booze) called the Finale, in LA’s Little Tokyo district, a club which Russell, one of its regular customers, described as a ‘West Coast Minton’s’ in its brief existence. Bird’s presence brought in the best of the emerging beboppers on the coast, and musicians passing through on tour would drop in to jam.

Five very lo-fi cuts recorded live at the Finale were included on Spotlite’s Yardbird in Lotus Land album, with a quintet which featured Miles Davis, pianist Joe Albany, Addison Farmer on bass, and drummer Chuck Thompson. (The album also features invaluable broadcast recordings in much better sound of the Gillespie quintet/sextet/septet during their stay in Los Angeles, probably from January, and an alto summit meeting with Benny Carter and Willie Smith.) The Finale was a short-lived venture, but during its tenure Parker cut his first session for Russell’s Dial Records, with the exception of an aborted affair with Dizzy and pianist George Handy, of which only a raggedy run-through of ‘Diggin’ Diz’, a contrafact of Richard Rodgers’s ‘Lover’, was completed. The four sides cut that day (28 March 1946) were all classic Parker creations, and, as in much of his work from the Savoy and Verve catalogues, survive in multiple takes, each featuring the saxophonist’s fabled ability not to repeat himself in his solos. The playing length of compact disc technology has encouraged companies to exhume a mountain of alternate and discarded takes to pad out re-issues or make up lavish collected editions. These are often of scant value, either in themselves or in what they add to our knowledge, but Parker’s are a different matter, and his alternates were among the first deemed worthy of re-issue on LP long before the compact disc made its appearance. His rejected takes (very often due to some lapse by a sideman) offer a constantly shifting view on his thought processes in negotiating the tune in question, not only in his chosen melodic and harmonic route, but also in tempo and rhythmic nuance, while Ross Russell has also observed that he tended to play best on early takes, which were often precisely those not released at the time.

The bustling ‘Moose the Mooche’ was built on the ‘Rhythm’ changes, ‘Ornithology’ on ‘How High the Moon’, ‘Yardbird Suite’ on ‘What Price Love’, and the session was rounded out with the Gillespie original, ‘Night in Tunisia’. Bird’s chosen trumpet-man was Miles Davis (whose playing still lacked conviction), with Lucky Thompson on tenor, and the fine, under-recorded west coast pianist Dodo Marmarosa. The rhythm section struggles at times, but Parker is in gloriously inventive form throughout.

That was certainly not true by the time he re-entered the studio at Dial’s behest for the ill-fated session of 29 July which precipitated the disastrous sequence of events which saw him committed to the federal hospital at Camarillo. Parker had been off heroin since the arrest of Moose the Mooche, but was drinking heavily, and both his behaviour and playing had become increasingly unpredictable. Trumpeter Howard McGhee had re-opened the Finale and taken Bird into his home, and it was he who organised the band for the session, despite both his and Russell’s fears regarding the outcome.

Parker was in a bad way, and the results have become notorious, notably his pained reading of Ram Ramirez’s ‘Loverman’, on which the saxophonist already seems on the verge of collapse. The recording has an awful fascination even now, and it is symptomatic of the veneration in which Bird was held by his followers that saxophonists actually learned and replicated the faltering, tortured chorus which he manages to squeeze from his horn, alongside his masterpieces. Bird never forgave Russell for releasing the four tracks cut that day, but they provide an all-too-vivid aural portrait of a man on the verge of complete breakdown.

The inevitable followed quickly. Parker was arrested that night after a fire in his hotel bedroom and some string-pulling by his admirers saw him committed to the best of the three state mental hospitals. It probably saved his life at that time, and while at Camarillo he was restored to the best health he had enjoyed in years. The resident physician assigned to the case suspected he might be schizophrenic, but Ross Russell reports that Richard Freeman (the brother of the co-owner of Dial, Marvin Freeman), a psychiatrist who had taken a particular interest in Bird before his incarceration, believed that the saxophonist exhibited a classic psychopathic personality.

A man living from moment to moment. A man living for the pleasure principle, music, food, sex, drugs, kicks, his personality arrested at an infantile level. A man with almost no feeling of guilt and only the smallest most atrophied nub of conscience. One of the army of psychopaths supplying the populations of prisons and mental institutions. Except for his music, a potential member of that population. But with Charlie Parker it is the music factor that makes all the difference.

Parker was also a master of the put-on, a trait observed by many, and was expert in disguising his feelings – as Miles Davis put it, ‘Bird always wore a mask over his feelings, one of the best masks that I have ever seen’. That almost schizophrenic change of face was noted by others, but as a symptom of lifestyle rather than basic personality. In his autobiography, Unfinished Dream: The Musical World of Red Callender, bass player Red Callender recalled working with the saxophonist on the coast during this period.

To most people Parker would have seemed a trifle remote because he was always preoccupied with his thing, music. He could sit and write out a chart in a matter of a few minutes. Anything he played he could put on manuscript. Charlie Parker was actually a brilliant man who was unfortunate enough to be into drugs. When he was straight, he was a beautiful person to talk to, he was well-versed, even erudite on many topics. Bird would talk Stravinsky or Bartók, he’d talk politics too. Often he’d discuss what was happening with President Truman, who was from his home state, Missouri. He was very articulate, had opinions on everything, especially the structure of the capitalist system and racism in America. Bird wasn’t at a loss on any subject, particularly when his head was together. When he was strung out he became another person.

He was released into the custody of Ross Russell early in 1947, and claimed much later that the record producer had made him sign a contract as a condition of release, a claim denied by Russell. The deal was struck, however, and it was a very different Parker who went back into the studio on 19 February with a band which also featured pianist Erroll Garner’s working trio, with Red Callender on bass and drummer Doc West, as well as Earl Coleman, an unpretentious Eckstine-style singer the saxophonist had discovered in an LA club. It was not the session that Russell had in mind, but it did produce two dazzling, impromptu instrumentals in ‘Bird’s Nest’ and ‘Cool Blues’, which not only provide a taster for the relaxed feel evident on Parker’s final Hollywood session for the label a week later, but benefit from the more spacious ensemble textures provided by Garner’s fine trio. ‘Cool Blues’ is especially good, and if you have the Spotlite issues of the complete Dial sessions on either LP or CD, it is intriguing to trace the evolution of the final master through the three alternate takes which preceded it, with a particularly overt reconsideration of tempo, which is clearly much to Garner’s liking.

While the septet featured in the second session looks a more homogeneous bebop unit than the trio, with Howard McGhee and Wardell Gray on their respective horns, and Marmarosa joined by guitarist Barney Kessell, Callender, and Don Lamond on drums, in practice the procession of soloists tends to get a little congested. In both sessions, though, Parker could hardly sound more different than he did on the fraught ‘Loverman’ date, and the benefits of rest and rehabilitation are obvious on his informal blues creation ‘Relaxin’ at Camarillo’, said to have been cooked up in a taxi on the way to the studio, and on three tunes wisely provided by McGhee on the assumption that the saxophonist was unlikely to show up with the four commissioned new pieces. They announced that Bird was back, and ready to resume the flight so rudely interrupted the previous summer. That resumption, though, was not to be consummated on Central Avenue, but back in the cradle of bebop, 52nd Street.

Before he left for New York, however, Dean Benedetti, already a devoted acolyte of the master, began to make the celebrated series of recordings which achieved an almost legendary status for over four decades. Benedetti was an alto saxophonist who experienced a conversion of almost religious intensity when he first heard Bird play. Between 1 March 1947 at the Hi-De-Ho club in LA, and 11 July 1948 at The Onyx on 52nd Street, he set up his recording devices in a number of clubs in the hope of preserving Bird’s gorgeous flights for posterity. And he did mean Bird. For the most part, he was interested only in recording the saxophonist, and either omitted or quickly cut off the other musicians on the stand, however distinguished or unique the occasion. The results constitute an astonishing, fragmentary, and in truth at times barely listenable record of obsession: Benedetti had the right idea in wanting to catch Bird’s evanescent creations on the wing, free of the artificial environment of the recording studio, but lacked the technical means to achieve it. Most of the fragments are in poor sound quality, but what they have to reveal about Parker’s methods as a creative improviser has helped flesh out the picture already available from the canonic sets of recordings on Dial, Savoy and Verve, as well as a whole range of broadcasts and other unofficial sources.

For a long time, though, it seemed as if the Benedetti recordings would remain firmly part of the Parker myth. A smattering of the material had been commercially released, but the huge majority of this remarkable archive was thought lost. In fact, they were in the possession of his brother, and were finally unearthed and lovingly assembled by Mosaic Records in 1990, as The Complete Dean Benedetti Recordings, a seven-CD set which, unlike all other Mosaic limited edition sets, will remain permanently available, since they own rather than lease the rights to the material. They are, however, likely to prove compelling only to the devoted and the scholarly.

Bird returned to New York early in April 1947, by way of a stop-over in Chicago to play a gig with Howard McGhee. He settled in the Dewey Square Hotel (commemorated in his tune ‘Dewey Square’), and put together a famous quintet for an engagement at The Three Deuces, playing opposite Lennie Tristano. The band featured Miles Davis (trumpet), Duke Jordan (piano), Tommy Potter (bass) and Max Roach (drums). There is some debate about the dates of this engagement, but in his autobiography Miles Davis puts the opening as April. Bird ‘seemed happy and ready to go’, Miles recalls, and the band had their work cut out in adjusting to his radical rhythmic experiments.

I was really happy to be playing with Bird again, because playing with him brought out the best in me at that time. He could play so many different styles and never repeat the same musical idea. His creativity and musical ideas were endless. He used to turn the rhythm section around every night. Say we would be playing a blues. Bird would start on the eleventh bar. As the rhythm section stayed where they were, then Bird would play in such a way that it made the rhythm section sound like it was on one and three instead of two and four. Nobody could keep up with Bird back in those days except maybe Dizzy. Every time he would do this, Max would scream at Duke not to try to follow Bird. He wanted Duke to stay where he was, because he wouldn’t have been able to keep up with Bird and he would have fucked up the rhythm section. Duke did this a lot when he didn’t listen. See, when Bird went off like that on one of his incredible solos all the rhythm section had to do was to stay where they were and play some straight shit. Eventually Bird would come back to where the rhythm was, right on time. It was like he had planned it in his mind. The only thing about this is that he couldn’t explain it to nobody. You just had to ride the music out. Because anything might happen musically when you were playing with Bird. So I learned to play what I knew and extend it upwards – a little above what I knew. You had to be ready for anything.

Miles paints a typically graphic image of the discomfited musicians as Bird launched into one of his flights: ‘Anyway, so then, sometimes Max Roach would find himself in between the beat. And I wouldn’t know what the fuck Bird was doing because I wouldn’t have never heard it before. Poor Duke Jordan and Tommy Potter, they’d just be there lost as motherfuckers – like everybody else, only more lost. When Bird played like that, it was like hearing music for the first time.’ That sense of freshness and surprise, though, is underpinned by an equally crucial element in his music: structural logic. Even in his wildest inventions, his most dazzlingly dense solos, Parker’s music is informed by a clear architectural sense of purpose, a remorseless musical logic which may have torn up expected preconceptions, but was thoroughly if intuitively thought through in the process of its creation (‘it was like he had planned it in his mind’). This was not only the expression of an exceptional musical intelligence, it was also the pay-off for all the wood-shedding of a decade before, which left him with the technical capability to realize the dazzling array of ideas and heightened emotions flowing through his horn.

With a typical disregard for such frivolities as contracts, Bird’s first recording session on his return to New York was for Savoy, despite his still-current ‘exclusive’ deal with Dial. The studio band featured a change favoured by both Miles and Max, which brought Bud Powell to the piano chair, despite the personal difficulties that existed between Bird and Bud and that would surface periodically over the years, culminating in an infamous occasion on Parker’s final appearance at Birdland, just days before his death. After a confrontation on stage, the pianist, drunk and all but incapable of playing, smashed some keys with his elbow and stalked off stage, leaving the saxophonist repeating his name over and over into the microphone. Eventually, as the tension became unbearable, Charles Mingus, the bass player for the date, apologised to the audience (‘This is not jazz. These are sick people’), and the gig – and Bird’s career – ground to a premature halt, although some observers have claimed that Parker played on as a trio without Powell and trumpeter Kenny Dorham, whose own account of the incident appears in Reisner’s Bird: The Legend of Charlie Parker.

On this studio date, though, Powell was in scintillating form, with the inner demons held at bay and the creativity in full flow on take after take. Potter and Roach provide a buoyant underpinning for the music, but a youthful Miles Davis sounds distinctly out of his depth much of the time (he would find his forte in a different direction by the end of the decade), and Bird is uneven, as an inspection of the four completed takes of ‘Donna Lee’ will readily confirm. Although Miles wrote the line (it was wrongly credited to Parker on the record), he struggles to play it and intonation remains a problem for both hornmen through all the takes.

While yet another contrafact on the ‘Rhythm’ changes, ‘Chasing The Bird’ is unusual in Parker’s discography in that it features contrapuntal lines for the alto and trumpet, rather than the usual unison statements, a refreshing shift of direction which we might wish he had followed up more often. Counterpoint was rare in bebop generally, although it was taken up with a vengeance in the so-called West Coast Cool style, and indeed, given his alleged chafing against the restrictions of form, it is surprising that Parker did not explore that possibility more fully. Two sharply contrasting blues, the serpentine ‘Cheryl’ (with Powell in formidable flow) and ‘Buzzy’, completed the session.

Bird played tenor on his next studio outing, a date for Savoy under the leadership of Miles Davis in August, with John Lewis on piano, Nelson Boyd (bass), and Max Roach (drums). The trumpeter sounds much more at home with the music this time around, while the bigger horn blunts Bird’s attack a little, but not his rhythmic or harmonic acuity. This is a relaxed and inventive session (one of only two Parker would record on tenor), and includes Miles’s first tune under the title ‘Milestones’ (he would write the other, better-known one a decade later), his adaptation of a Tadd Dameron line as ‘Half Nelson’, a sophisticated blues in F he called ‘Sippin’ at Bells’, and the bustling ‘Little Willie Leaps’, the tune which would precipitate the bust-up with Powell at Birdland (the pianist insisting on playing it when the rest of the band were playing something else entirely). Bird was on a roll, however, and 1947 would be widely seen as marking the start – and perhaps the apex – of his period of greatest ascendency in the music, one which lasted until the early part of the next decade. He was off heroin at this point, although drinking heavily, and the recordings left to us clearly reveal the saxophonist restored to full command of his mature powers.

Dial were finally able to get their ‘exclusive’ signing back into a studio for a series of three sessions in October, November and December 1947, which completed his output for the label, although a home jam session at the house of Chuck Kopely in Los Angeles is also included in the complete issues of the Dial material, recorded Benedetti-style by Howard McGhee with a hand-held microphone, leaving the other musicians largely inaudible. It is all too indicative, incidentally, of the neglect of jazz in its homeland that it was left to a tirelessly dedicated English ornithologist, Tony Williams, to gather and issue the definitive collection of the complete Dial recordings on his Spotlite label in the late 1960s.

The Dial sessions provide a strong indication of why Parker preferred the relative anonymity of Duke Jordan (or the even more sympathetic Al Haig) to the quirky individuality of Monk or the ebullient dazzle of Powell, and the cool, understated middle-register work of Miles over the pyrotechnics of Gillespie or Navarro. The group is designed to support and complement the brilliance of his own playing and his own harmonic conception, and another incendiary talent on or near his level was likely to prove a distraction. The exception, of course, was the drummer, and while Bird valued the solid support of a compliant rhythm section, he also saw the necessity of having it fired up by Max Roach’s incomparable drumming (though sadly, the finer details of his work are not convincingly captured by the recording processes of the time).

The October session added six tunes to his discography, including arguably his finest ballad performance in the studio on ‘Embraceable You’. The ensembles have that lived-in feel which only comes with night after night spent together on the stand, and the now-familiar structures dominate, with three AABA tunes (‘Dexterity’, ‘Dewey Square’ and ‘Bird Of Paradise’) and two blues (‘Bongo Bop’ and ‘The Hymn’). His control of tension and release is startlingly evident on ‘Dexterity’, a ‘Rhythm’ contrafact in which he explores the alternation of measured phrases with sizzling double-time passages in a masterly exhibition of musical and emotional control, but one which feels entirely organic and unforced. That ability to combine exhilarating spontaneity with impeccable balance is a constant of his best work.

Bird was clearly in more reflective mood on the November session. Unusually, three of the six tunes were ballads and, equally unusually, two of them, ‘My Old Flame’ and ‘Don’t Blame Me’, were gracefully dispatched in a single take. The three takes of ‘Out Of Nowhere’, although made only minutes apart, provide another fascinating example of his ability to radically redefine his approach to the same tune, while the uptempo cuts include two more classics, the phonetically titled ‘Klact-oveeseds-tene’, a fine example of his ability to build a brilliantly coherent solo out of seemingly fragmentary phrases, and ‘Scrapple from the Apple’, taken at the ‘medium bounce’ tempo he loved, and built in part on one of the first tunes he ever learned, Fats Waller’s ‘Honeysuckle Rose’, but with an altered bridge. The session began with the inevitable blues, a concoction entitled ‘Bird Feathers’.

His Dial output was completed the following month, this time with trombonist J.J. Johnson drafted in to enlarge the band to a sextet. The first thing which strikes the ear is the additional lustre of the alto sound, courtesy of a brand new Selmer saxophone which Bird had acquired just before the session. The trombonist dovetails neatly into the ensemble, and his own solo statements reveal how far he had progressed in tailoring his intractable horn to the demands of the bebop idiom, and vice versa. The session contains another version of ‘Embraceable You’, this time in a medium bounce version entitled ‘Quasimodo’, a furious version of Benny Harris’s ‘Little Benny’ re-cast as ‘Crazeology’ (of the four extant versions, two have survived only as alto solos), and ‘Charlie’s Wig’, a choice contrafact of ‘When I Grow Too Old to Dream’, as well as the blues tunes ‘Drifting on a Reed’ and ‘Bongo Beep’, and a ballad, ‘How Deep is the Ocean?’

At the time he was making these sides, Bird also took part in a series of broadcast sessions which reflect the in-fighting of the period. The post-war years saw a concentrated animosity between jazz’s traditional wing (dubbed the ‘mouldy figs’, often with the mock-anachronistic spelling ‘fygges’ to underline the point), and the emerging modernists, whose champions in the press included the editors of Metronome, Leonard Feather and Barry Ulanov. In September, Ulanov organised a battle of the bands on radio, with his own hand-picked selection going up against the resident band on Rudi Blesh’s This Is Jazz show, with a programme billed as ‘Bands For Bonds’ as the chosen battleground. Parker took part in all three sessions in September and November (the latter a celebration for the triumphant modernists, who won the listeners’ votes). The tapes have survived and were issued – again by Spotlite – in the early 1970s, with the altoist in typically fine fettle. For lovers of the curious, the second session of 20 September includes a radical re-interpretation of the New Orleans warhorse ‘Tiger Rag’, with Bird and Dizzy taking no prisoners. Their version prompted Ulanov to comment in the November issue of Metronome that what they did with a tune which was ‘entirely new to all of them as a piece to perform, surely must rank high in jazz history. Its remorseless progression from B flat to A flat to E flat was never accomplished with more ingenuity and less confinement’.

Shortly after that second broadcast, Bird and Dizzy were reunited again, this time on the stage of Carnegie Hall, where the saxophonist appeared as Dizzy’s guest in a concert which, as the play-bill proclaimed, brought The New Jazz to that august venue, and featured the trumpeter’s big band and singer Ella Fitzgerald. Parker received secondary billing (perhaps in part because his notorious unreliability left doubts as to whether he would actually show up), and joined Dizzy on five quintet tunes after the interval, with a rhythm section drawn from the big band, featuring John Lewis (piano), Al McKibbon (bass) and Joe Harris (drums). The music they played that night was recorded and has been issued in various forms, initially by a pirate company called Black Deuce as 78 rpm discs, and later in legitimate form by Savoy. The rivalry between the two mainstays of bebop is readily apparent as each pushes the other to more and more remarkable feats – both musical and athletic – and the rhythm section comes close to surrender at times, notably on a furious ‘Dizzy Atmosphere’ and ‘Koko’, all spurred on by their partisan supporters in the sell-out crowd. The result has to be declared an honourable draw, with the music the ultimate winner.

The final Dial session had been cut in the shadow of another recording ban called by James Petrillo of the American Federation of Musicians and scheduled to commence on 1 January 1948. Savoy, however, managed to get the quintet back into the studio for one final pre-ban session in Detroit on 21 December. ‘Klaustance’ and ‘Bird Gets the Worm’ are particularly interesting products of this session (which was completed by two blues, ‘Another Hair-Do’ and ‘Bluebird’). There is no ensemble statement of the theme in ‘Klaustance’ – Parker launches directly into a searing improvisation right from the first bar, and it is only a brief nod in the final measures that give away its distant harmonic grounding in Jerome Kern’s ‘The Way You Look Tonight’. On ‘Bird Gets the Worm’ he does the same thing, only at an even faster tempo, and perhaps with a very slight melodic hint of its distant progenitor, ‘Lover Come Back to Me’, on the opening chorus of the first take. The saxophonist had never paid a great deal of attention to themes in any case, treating them largely as launching points for the serious business to come, and the sprinkling of such tunes where he ignores the theme altogether (‘Bird’s Nest’ is an earlier example) seems to allow him an even greater freedom of expression. He adopts fearsome tempos in all of them, but the surge of ideas flowing from the saxophone is even more unfettered than usual and never falter. ‘Bird Gets the Worm’, incidentally, also contains an early example of a device that would eventually become a bop cliché, the exchange of improvised four-bar phrases with the drummer and bassist Tommy Potter. Known as ‘trading fours’ (or ‘trading eights’, depending on the measure used), it became – and remains – a staple final chorus interchange between soloists and their rhythm players.

It was to be the last session for this particular line-up. By the time Parker completed his recorded output for Savoy in the latter part of 1948 (in sessions arranged in clandestine contravention of the ban), he had a new rhythm section, with John Lewis replacing Jordan, and Curly Russell taking over from Potter. The two sessions in September produced eight more sides, including his only other contrapuntal theme, ‘Ah-Leu-Cha’, and an interesting Latin-based blues extemporisation, ‘Barbados’, which prefigured projects to come. ‘Constellation’ became a favourite bop blowing vehicle, as did ‘Steeplechase’, laid down in one take (and a fragment of false start) after twelve attempts at ‘Marmaduke’. Both these tunes were part of a generally less spectacular second session, although one which has its share of characteristically sublime moments as well, notably on the vibrant ‘Merry Go Round’. A blues, ‘Perhaps’, completed the session. ‘Marmaduke’ provides further justification of the real value in issuing the alternate takes: the final master (take 8) is arguably the best ensemble version of the tune, but equally arguably not the saxophonist’s best solo performance. There are numerous examples of that situation which recur across his work, and provide endless matter for discussion and argument.

The masterpiece of that month’s work in the studio, though, and one of his finest creations on disc, was the incomparable ‘Parker’s Mood’, a slow blues which rounded out the first session. It is one of the most expressive blues performances ever committed to record by anyone, and it could be said that Parker’s most intense display comes on the opening chorus of the rejected first long take (take two), which is both slower in tempo and darker in mood than the eventual master, but breaks down just before the coda. The slightly faster master (take 5), while more relaxed and still unquestionably sublime, does not capture quite the same level of heightened emotion and poetic clarity as the saxophonist’s initial effort. Fortunately, the listener has both options readily available.

Parker made his debut at the Royal Roost, a chicken restaurant and jazz club on Broadway, on 3 September 1948, and for a time the venue became the new focal point for modern jazz, in large part as a result of the regular broadcasts made from the club. These were presented by ‘Symphony Sid’ Torin, whose dated spiels survive on most of the record releases of these broadcasts from what he dubbed the Metropolitan Bopera House. These recordings, issued in various forms on the Savoy label, are arguably the single most valuable body of Parker’s live recordings which have come down to us. Recorded between 4 September 1948 and 12 March 1949, they provide a snapshot of Bird’s working band caught outside the confines and restrictions of the studio, sometimes augmented by guests, and in decent sound (at least by comparison with the Benedetti tapes) and complete versions.

It was at the Roost at Christmas 1948 that Miles handed in his notice by stalking angrily from the stage, complaining that Bird ‘makes you feel about one foot high’. In his autobiography, he refutes the much-repeated suggestion that he walked out of the gig for good in mid-set, but confirms that his relationship with Bird – apparently never very close on a personal level in any case – had become irreparably strained. Arguments over money and his professed disdain for Bird’s clowning brought matters to a head, and the trumpeter departed to be replaced by McKinley Dorham, who abbreviated his forename as Kinny but eventually gave up and settled on the misrepresentation which everybody actually used, Kenny. Al Haig was also now the regular piano man in the quintet (another source of friction with Miles, who favoured either Lewis or Tadd Dameron, the pianist featured on the opening night at the Roost).

If 1947–48 were arguably the years of Parker’s peak musical achievements, certainly in terms of consistency and creative discovery, it was in 1949 that he began to gain the kind of public recognition which had so far eluded him. In November 1948, he signed a recording deal with Norman Granz (in addition to the JATP recordings, Granz had made two sides featuring Bird for a limited edition compilation a year earlier), the first fruits of which were a vibrant Cubop session with Machito and his orchestra in December, which realised the two-part ‘No Noise’ and the exuberant ‘Mango Mangue’, although a second session the following month was less successful, with Bird cutting only one side, ‘Okiedokie’. It was the beginning of a long and often productive relationship with Granz, initially for the Mercury label, and later for Granz’s own labels, Clef, Norgran, and ultimately Verve. It is the largest single portion of Bird’s confused discography, although the overall standard is not as breathtakingly high as the Dial or Savoy sides, in part due to Granz’s penchant for introducing unsuitable guests into an otherwise promising line-up.

Chico O’Farrill’s Afro-Cuban Suite, which was recorded in December 1950 but not released in full form until the late 1970s, and not in a good sound source until the Verve box in 1988, was a more ambitious collaboration with Machito, although, according to the composer, Parker seems to have been a late choice as one of the jazz soloists, stepping in when Harry Edison withdrew from the project. He was back in a Latin groove on the sessions of 1951–52 which made up an album released as South of the Border where he explored Latin, Mexican and Caribbean rhythms – indeed, the calypso groove of ‘My Little Suede Shoes’ provided him with his second most successful single release.

Bird visited Europe with his quintet for the first time in 1949, where they played several dates in France, and returned again in 1950 to Sweden, Belgium and France (recordings survive from both tours). The latter visit was cut short by a peptic ulcer which hospitalised him on his abrupt return to New York, when he should have been playing in Paris. Whatever reservations he may have had, he found the respectful reception he received there a sharp contrast to the prevailing ethos in the USA, and even talked of joining the expatriate jazz community scattered around Europe. In fact, he was never to return.

Just before the first tour, he cut two sessions for Granz, the first with guests Tommy Turk (an early example of that incompatible JATP-style mis-matching) and Carlos Vidal. The second session was the only occasion on which Granz recorded Bird’s working quintet of the day without the augmentation of guests or stand-ins. The sessions with Machito suggested that Bird was now ready to experiment beyond the small-group bebop idiom, and his next studio visit at Granz’s behest certainly achieved that aim.

The ‘Bird with Strings’ recordings have always been controversial. Many hipsters and followers of the true bop religion saw the move as a commercial sell-out, probably engineered by Granz, but Parker himself refuted that suggestion, claiming that ‘I was looking for new ways of saying things musically. New sound combinations’. He added that Granz was simply allowing him to fulfil an ambition he had nurtured since the early 1940s. He spoke often of his admiration for classical composers, notably Stravinsky and Bartók among the modernists, but there is little of their power or invention evident in his own efforts in this context. There had been a dry run of sorts the previous year when Bird soloed on ‘Repetition’ with the Neal Hefti Orchestra, which included a string section, for Granz’s compilation album. The fully-fledged strings project required numerous sessions to complete, however, although the finished releases are generally attributed to the session of 30 November 1949. Bird was joined by a jazz rhythm section of Stan Freeman (a studio player with some jazz chops), Ray Brown and Buddy Rich, and a string group of classical musicians under the supervision of Mitch Miller, which included violin, viola, cello, harp and oboe playing arrangements by Jimmy Carroll, who also conducted.

Hard though it is to believe, Parker seems to have felt a genuine inferiority complex in the presence of classically-trained musicians, even though they were not remotely on his plane as a creative talent, and seems to have approached the sessions with considerable anxiety. The first set of releases in this format produced the most fully realised cut, a lovely version of ‘Just Friends’ which gave the saxophonist the biggest single hit of his whole career. In ‘Just Friends’, Bird and his collaborators found the optimum balance between his characteristically hard-edged, astringent alto style and the sweet, poppy string arrangements which are distinctly cloying on some of the other efforts from this session, and from the two subsequent studio dates in this format, in the late summer of 1950 and early in 1952, both of which featured arrangements by Joe Lipman. Bird also played tour and club dates with strings, and there are live recordings from the Apollo, Carnegie Hall and Birdland.

The most successful performances are generally those where Bird is able to free himself most emphatically from the insipid accompaniments. Nonetheless, he continued to work intermittently with strings until a disastrous night at Birdland, the Broadway club named after him, in August 1954. The scheduled three-week engagement began well enough, but as the first week wore on, Bird became increasingly argumentative with his sidemen, culminating in a stand-up row on the bandstand, and the public firing of the string players. He was banned from the club which bore his name at a time when his personal health and state of mind were already much battered – his daughter with Chan Richardson, Pree, had died earlier that year while he was working on the west coast, a loss which profoundly affected him. That night, he attempted to commit suicide by drinking iodine; his stomach was pumped at Bellevue and he survived, but not for much longer.

Parker’s decline in the 1950s was by no means a uniform one, at least in artistic terms. His drug-free interlude in the wake of Camarillo had been a short one and the cumulative effects of drugs and alcohol on his health grew inexorably more serious. He bickered with his various managers and agents, including the long-suffering Billy Shaw, battled with club owners, ran into trouble with the union over failure to fulfil engagements and pay his sidemen, and had his vital cabaret card revoked in 1951, without which no musician could undertake regular nightclub work in New York. Deprived of the crucial base of regular engagements in the city, he was forced to take on more out-of-town engagements as a soloist working with local rhythm sections. His employment became increasingly sporadic and the measure of financial success he had begun to enjoy in the late 1940s turned instead to mounting debts.

Nonetheless, he continued to produce memorable music throughout his final half-decade, both in the studio and, on the evidence of the surviving live recordings, on stage, where the lucid flow of his boundless invention is often worked out at greater length. The studio session reuniting him with Dizzy Gillespie and Thelonious Monk on 6 June 1950 was marred by Granz’s inclusion of the stylistically inappropriate Buddy Rich on drums, but both hornmen are in fine, highly characteristic fettle on ‘Bloomdido’ and ‘An Oscar For Treadwell’, the picks of the session, although Monk is more self-effacing throughout than posterity would have wished. It was the last time Bird and Diz met in a studio, although subsequent occasional live dates have been preserved, including sides from Birdland in 1951 and the famous concert from Massey Hall in Toronto in 1953, which does not quite live up to its frequent on-disc billing as ‘The Greatest Jazz Concert Ever’ but is essential listening nonetheless, bringing together as it does the titanic talents of Bird, Dizzy, Bud Powell, Charles Mingus and Max Roach on a single stage.

There was a further studio reunion on 17 January 1951, this time with both Miles Davis and Max Roach in a quintet which also included Bird’s regular piano-man of the period, Walter Bishop, Jr, and bassist Teddy Kotick. ‘Au Privave’ is arguably the classic outcome of the session, which also yielded ‘She Rote’ and ‘KC Blues’, as well as a re-make of ‘Star Eyes’, which he had cut with a quartet the previous year. (Miles went on to make his recording debut for Prestige later that same day, and one of his subsequent sessions for the label would feature Bird, credited as ‘Charlie Chan’ for contractual reasons, on a rare tenor outing in 1953, which Prestige released on LP as Collectors Items.) These sides were later combined with a quintet session of 8 August as the LP Swedish Schnapps. The second session featured trumpeter Red Rodney, who had taken over as Bird’s regular trumpet-man the previous year, and the rhythm section which would provide the platform for the formation of the Modern Jazz Quartet with Milt Jackson, comprising John Lewis (piano), Ray Brown (bass) and Kenny Clarke (drums). The title track is again vintage Bird, while ‘Si Si’ and ‘Blues for Alice’ are not far behind. In an interesting historical footnote, he also returns to ‘Loverman’ – according to John Lewis, in response to a special request from Granz – but does not sound fully committed to a tune which presumably held bad memories from the infamous Dial version. If, as Red Rodney has suggested, it constituted some kind of purging of that memory, it does not sound like an entirely effective one.

There is some doubt over the actual dates of the quartet session which produced four more eminently worthy contributions to the Parker discography in either December 1952 or the following month. The sparkling ‘Kim’ and more relaxed ‘Laird Baird’ are both dedications to his children (Chan’s daughter Kim, and his son with her, Baird), while ‘Cosmic Rays’ is another blistering blues performance and ‘The Song is You’ a fine medium tempo treatment of that ballad. Whatever his personal state – and the decline was now well underway – the saxophonist could still rise to the occasion in the studio, and with a remarkable consistency of invention which belies his problems outside. Time, though, was starting to run short on one of jazz’s most spectacular flights.

The only other small-group session of 1953 saw Bird eventually turn up with only 45 minutes of the scheduled three-hour session left. The quartet – old hands Al Haig (piano) and Max Roach (drums), plus a slightly bemused Percy Heath on bass getting his first taste of Bird’s methods in the studio – brought the session in on schedule in the remaining time, with six full or partial takes of ‘Chi-Chi’, first time hits on ‘I Remember You’ and ‘Now’s the Time’, and, after two false starts, a rampant ‘Confirmation’. Max Roach had already recorded ‘Chi-Chi’, and recalls Parker sitting at the table in his basement apartment in the middle of the night writing the tune straight off ‘like a letter’ as a gift for the drummer’s debut recording session as a leader, which he was scheduled to make the next morning.

Bird’s last two small-group sessions were both for quintet, although it seems likely that he added guitarist Jerome Darr to a planned quartet date on one of his infamous last-minute whims for the session on 31 March 1954, and maintained that instrumentation on the 10 December date, but with Billy Bauer on guitar. The material was all from the Cole Porter book and the project was intended to be the first of what became a Verve trademark, the Songbook project. He also took part in the first of Granz’s JATP-style studio jam sessions in June 1952, and there were also studio ventures with a swinging big band (four sides recorded on 25 March 1952, with Joe Lipman as arranger and conductor) and a more experimental orchestra session under Gil Evans on 25 May 1953, which included a ‘Birth of the Cool’-style instrumental line-up with French horn, clarinet, oboe and bassoon alongside a jazz rhythm section and a sugary mixed vocal chorus led by Dave Lambert. Parker had spoken in Down Beat in January about his desire to make such a session, this time citing Hindemith as a precedent, but the attempt proved unsatisfactory. Both Evans and Bird blamed faulty engineering balances and offered to do it again but Granz, who disliked it intensely, refused the offer and the Parker – Evans combination remained one of unrealised potential.

By 1955, Bird’s health was in serious decline, and a number of musicians have reported him making portentous remarks about not being around much longer, including Dizzy Gillespie, Sonny Stitt and Charles Mingus (on the night of the Birdland debacle on 5 March). His gloomy predictions proved all too accurate. By the time he dropped into Nica’s apartment, he was very ill indeed, and the Baroness’s doctor would not allow him to travel to Boston, where he was booked as a soloist with a local rhythm section at the Storyville club. His death briefly stirred a mainstream press scenting a possible scandal, as the ‘bop king dies in heiress’s flat’ headlines in the popular sheets confirm, but they quickly lost interest again. His funeral arrangements became another source of dissension, as Chan, his final partner but never his wife (Bird had never gotten round to divorcing his third wife), and his first wife, Rebecca, disputed the right to bury him. Rebecca won out and he was interred in Kansas City, with a service which seemed totally inappropriate.