Читать книгу To Cap It All - Kenny Sansom - Страница 20

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

TERRY AND KENNY

ОглавлениеTerry Venables and I clicked straightaway and I think this was as much to do with our similar personalities and sense of humour as our passion for football. I had always been a joker and loved the old comedians – as did Terry. We both found the old-school types such as Tommy Cooper hilarious. He had a bar called the Laurel and Hardy, and once we did a fine rendition of these two old comedians, but we rarely got into ‘a fine mess’ the way they did. On the contrary, we rarely messed up. These were golden days – days of hard work, laughter and innocence.

Being an apprentice in a big club in the seventies was bloody hard work – but, as Terry was telling me often, ‘The harder you work, the luckier you become, Kenny.’ So I got stuck in. Some days the other boys and I would be pushed so hard running around the track that we’d fall in a heap afterwards. Some of the others were actually vomiting, and the sweat would be pouring off us.

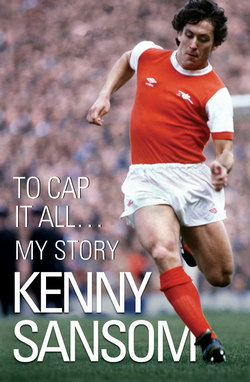

I was a young member of the team and very fit, so I coped better than most. (In fact the photograph on the front cover of my book was taken just after one of these runs.) I remember watching George Graham, who was a senior player, gasping for air as he slumped on the ground. Life for us could be quite gruelling and much harsher than the lads today have to contend with. It would be commonplace for us to clean out the referee’s room (and, trust me, the ref’s room could be a right old smelly place – it was a good job Robbie Savage wasn’t around then).

During preseason training we’d paint the stadium. Imagine that happening today.

Can you see John Terry and Frank Lampard getting busy with a paintbrush during the hot month of July? I don’t think so.

I wouldn’t have had it any other way, though – and I really mean that. I honestly think that, had I been a part of this football world today, when wages and temptation are ridiculously high, I would have totally, totally, self-destructed. The discipline and positive mentorship I received was worth its weight in gold and saved me just in time from that self-destruction.

You know something? There’s hard work that is exhilarating, and then there’s hard work that is a bloody drag. Fortunately, my kind of work fell into the former category. At the end of the day I’d literally collapse into the chair with exhaustion. The day had been a great big ball of fun and, as the evening turned into night, I fell asleep with a great sense of satisfaction at a job done well.

In my early days at Palace I took great pride in shining the boots of some of the big names of the day, like Jim Cannon – a rarity who chose to spend his entire 16-year career with one club. I also polished Nicky Chatterton’s boots. He was a highly industrious midfielder and I was later to play alongside him in the ‘Team of the Eighties’. Another teammate was the legendary Dave Swindlehurst. It really was quite something for a youngster like me to be surrounded by such talent.

We all ate hearty food such as pies, pasties, sausage rolls and chips. We also played our hearts out in our quest to take our team to promotion.

My mind still held onto a childlike quality and it rarely crossed my mind that I had been signed by a famous club, that I was being coached by a man destined to become a legend, and that I was in a prime position to realise many a schoolboy’s dream. I didn’t think about ‘being a pro’. I was simply having fun. Being coached by Terry Venables and Don Howe was quite something.

I wasn’t sure about our ‘kit man’, though – he troubled me somewhat. At 6 foot 2 inches, he towered above me, and his name was David Horne. He wasn’t sinister, but I couldn’t understand how his mind ticked. I was used to kindness and consideration and I felt he was less than gracious when he declined to give me a lift home, even though he drove past the end of my road.

I’d look into his mustachioed face and gingerly ask him, ‘Are you going to be long, Mr Horne?’ This was a subtle way of saying, ‘Give us a lift, mate. I hate doing this bloody bus journey on my own!’ But I wasn’t brave (or cheeky) enough to say, ‘I hate travelling alone, Dave.’

But I have a hunch he looked upon me as an annoying little bugger he wanted to avoid. He’d say, ‘Sorry, Kenny, I’ve got masses to do here yet.’

So, off I’d trot to the bus stop and then, as I stood in all kinds of weather, he’d sail past me in his comfy car without as much as a backwards glance. How can you do that to an eager kid who would give his last Rolo away? I suppose it takes all sorts to make the world go round.