Читать книгу Indonesian Gold - Kerry B Collison - Страница 22

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

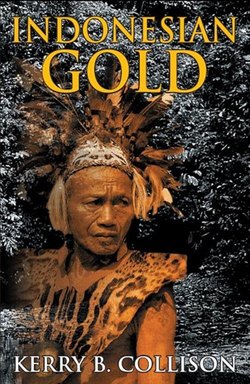

Indonesian Borneo (East Kalimantan ) Longdamai – Mahakam River

ОглавлениеOnce test drilling along the Mahakam River’s reaches showed substantial traces of gold, excitement swept through the villages and, in less than a year, a flood of prospectors from neighboring provinces inundated the stretches along the once-deserted riverbanks. The effects had been catastrophic for the Mahakam Dayaks – not least amongst these, Jonathan Dau’s Penehing whose lands would soon come under threat. He had ventured downriver to the provincial capital, Samarinda, to seek the Governor’s support in stemming the flow of illegal miners, his pleas falling on deaf ears. Gold fever had reached new levels within the corrupt, local Administration, with officials accumulating mining lease titles via their cronies in Jakarta’s Ministry of Mines. As the State maintained ownership of all natural resources, gold concessions were naturally allocated to vested interest groups associated with the Central Government. Increased foreign investment activity along the Mahakam reaches brought an even greater influx of Madurese and Javanese, the Dayak communities becoming increasingly incensed with these migrant groups’ complete disregard over local claims. Although the Longdamai mining rights originally belonged to Dayaks, somewhere along the line officialdom managed to secure these on behalf of a number of Samarinda Chinese businessmen who, subsequent to a number of catastrophic forays into the area, abandoned the site. Within weeks, itinerants had appeared, equipped with the most simple of tools, and started digging, their numbers so great the Dayak chief believed that it would only be a matter of time before all Penehing communities were overrun. Not surprisingly, sprawling shantytowns began to appear along the Mahakam, Dayak communities in Longbangun and Batukelau already under threat.

The wave of illegal miners not only occupied traditional land, but brought with them one of the most dangerous of substances known to man – the highly toxic, liquid metal, mercury. Jonathan visited the Longbangun camp, observing the archaic methods used by the miners in the extraction process. Shafts, barely large enough for one man let alone several, had been dug, thirty and forty meters underground, the men unable to swing their hand-picks more than a few centimeters in the cramped and poorly-lit tunnels. Of course, many had already been killed, most buried under tons of rock and soil, the result of poorly shored shafts. But it was the long-term effects of their presence that worried Jonathan most. The ancient process utilized in the crude extraction of gold was poisoning Dayak lands and, undoubtedly, rivers and streams.

He observed as the potential, gold-bearing rocks were crushed by hand and large amounts of mercury were added to small, manually rotated barrels to separate the gold. Jonathan watched as the mercury was strained, and then burned, the deadly gas given off going straight into the atmosphere. None, of course, wore any form of protective clothing such as gloves or masks. Once the precious yellow metal had been extracted, the workers would then discard the deadly residual along the riverbanks where they took their drinking water, washed their bodies and clothes, and fished. It was far too soon for the inevitable symptoms to appear; and, when these did, he knew that the cause of their skin and gum diseases would all be disguised by ignorance.

Depressed by what he witnessed, Jonathan Dau became impatient for Angela to complete her studies and return home, where they could work together to prevent the further spread of devastation to their precious forests and land.

****