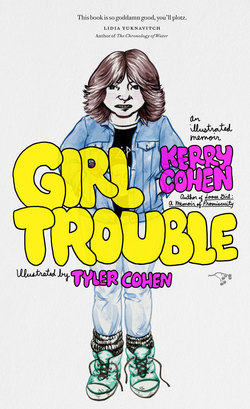

Читать книгу Girl Trouble - Kerry Cohen - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеPREFACE

Tyler

IN THE BEGINNING, THERE WAS TYLER AND ME. I FOLLOWED her around, wishing I could do the things she did. I remember chasing her through tall grass. I remember watching her on the jungle gym. She was always more athletic than I was. That was the time she accidentally knocked a board down and it hit me square on the nose because I had bent my head back to see her, see her going up and up away from me. It’s my one scar. I wore her hand-me-downs, her clothes mine, her scent mine. Tyler and Kerry. Unknowable apart.

When I was seven and she was nine, we started fighting. Bad fights where she punched, and I pushed and ran. Our mother gave us separate rooms then. She had to. This, I think, is when we began a necessary separation. Tyler, and then Kerry.

Next there were friends and boys and our parents’ divorce. It was an ugly divorce, fraught with affairs and devastation and anger. Our mother chose Tyler for her ally. Our father chose me. We visited our father every other weekend and for dinner on Wednesdays, and we sat in opposition to each other, fierce eyes, hungry hearts. When our mother left us with our father to pursue medical school in the Philippines, Tyler got left in a deeper way. She retreated to her room. She got into things I didn’t, like punk music and alternative clothes. And I got into boys, whatever it would take to get into boys.

I called her names I can never take back. I told her she was a lesbian, like that was a bad thing. I told her she was a loser, that she had no friends. I don’t remember her ever calling me names back.

I hated her because I hated my mother. For never allowing me to have my feelings, for controlling who I was and where I went, even from overseas. I didn’t care that she left me. But Tyler seemed ruined to me, and so I hated her for leaving Tyler alone. Hated that I had to care. Hated the ways in which I felt guilt.

Once, I came home from school, and Tyler had locked herself in our father’s bathroom. I knew there were pills in there. I’d already stolen a couple. My father was an addict—pot, cocaine, pills. He was a functional addict, but he was an addict nonetheless. The kind that kept himself removed from us, just enough so that Tyler and I were alone in this wilderness of our adolescent lives. And now Tyler was locked in the bathroom. I knocked once.

“Tyler?” I asked.

I heard a glass clink, then something fell to the floor.

“What?” she said.

“You okay?”

“Fine.”

I went back to the living room, my swollen heart in my throat. I waited, bouncing my leg. Waiting, waiting. Finally, I heard the toilet flush and she came out.

“Hey,” she said, when she saw me sitting there. The divide between us was so long, so deep. I couldn’t imagine how to cross it.

“Hey,” I said back.

“I have a headache is all,” she said.

I nodded, didn’t know what to say.

“Okay,” I said finally.

It was the closest we would get for many years.

She left for college. She grew up and out. Eventually, she got married, and then divorced. And then married again. She gave birth to a daughter. I got married, and then divorced. I had two boys, one with autism, and then I married again too.

We did things differently, and she felt criticized by me. I had an autistic child, and I felt that she didn’t care.

Also, though, I didn’t want to share myself with her. I didn’t want closeness or intimacy. Not with her, not with anyone. There was a period of time that was true.

Slowly, we found our way back. We were survivors, after all. Just her and me. Tyler and Kerry. We were the only ones who knew. Who know. Something happens as you grow up. Barriers matter less. Differences do too. You reach for people. You know time is limited, and that some things that mattered before stop mattering so much.

Last year I asked Tyler to work on Girl Trouble with me. Tyler was my first female friend, after all. My first trouble with a friend. She was there. She was there. And now here we are together, matched through blood, chosen through love. Sisters.