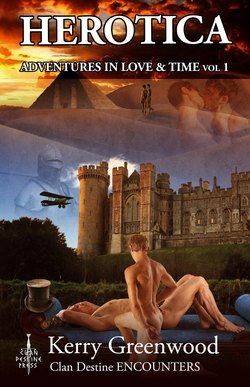

Читать книгу Herotica 1 - Kerry Greenwood - Страница 6

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

THE LIBRARY ANGEL

ОглавлениеLIBRARY OF ALEXANDRIA, ROMAN CONQUEST EGYPT B C 30.

The smoke was already trickling under the closed door. Marcus Tullius Corvinus grabbed the Homeric hymns, which he had been construing, and grappled them to his breast. Whatever the cost, these should not burn, must not burn. The scroll was heavy but he managed to seize a couple of epics as he ran past, seeking the outer gate into the colonnade that gave directly onto the sea.

The scrolls were inscribed in oak-gall ink. Even if they got soaked, they would not blur. The immortal words would not be lost to the night or war and barbarity, roaring towards scholarship and learning, knowledge and wisdom, with the fires from the burning ships. The library of Alexandria was a great monument and treasure of the world. The Romans probably wouldn’t mean to burn it down. But they wouldn’t overly care if they did.

Marcus got to the gate and a rush of flame, gusting with the high wind, forced him back. He stumbled into another scholar on the same errand, Egyptian by the look of him, a load of treatises in his arms.

‘The wooden fence and landing stage is afire,’ he gasped, ‘and there’s smoke coming under the other door.’

‘Windows?’ asked the Egyptian. They scanned the room. There were a few windows, but they were high up, too high for either of them to reach alone.

‘Take the scrolls,’ ordered Marcus. ‘I’m Marcus, what’s your name, fellow scholar?’

‘Imhotep,’ said the Egyptian. The kohl around his beautiful eyes was running down his face in black tears. ‘What do you intend?’

‘I’ll boost you up, you can get out through the window,’ said Marcus. ‘Take the Hymns of Homer with you, they must not be lost.’

‘But you’ll die,’ protested the Egyptian. ‘I would not leave you to perish.’

‘What scrolls do you have?’ asked Marcus, pulling a table over to the wall and climbing on it.

‘Treatise on Surgery, there’s only one, it saves lives,’ said Imhotep. ‘All of it, eight scrolls. That, too, must not be lost.’

‘This window faces onto the stone landing stage where the foreign ships come in. If we wrap them in something, make a bag, that ought to work.’ Marcus dragged off his tunic, piled the scrolls into it, and pinned it shut with his fibulae. The brooches kept the cloth close around the precious writing.

‘Now, up you go,’ urged Marcus. ‘If you stand on my shoulders, you can reach the opening. Hurry, it’s getting hard to breathe.’

Imhotep scaled the naked frame of the young Roman, dragged the scrolls to the window and shoved them out. But there was not a chance that he could fit his body through that narrow embrasure. Imhotep half slid, half fell, into the embrace of Marcus Corvinus.

‘We can’t get out,’ whispered the Egyptian, taking them both to the cold stone floor, where there was still a little air. ‘But the scrolls are safe.’

The Egyptian drew his fine woollen cloak over the two of them, so that they should not feel the teeth of the fire. Marcus Corvinus wrapped Imhotep in a fast embrace.

‘It is an honour,’ he gasped, as darkness crept over his sight, ‘to die with such a devoted scholar’.

Imhotep prayed while he could still form words, then snuggled into the Roman’s body. To die was to return to one’s mother, to go back to the source of all comfort. To die was to sleep the deepest sleep of all.

They slept. The fire roared overhead, licking up words, Greek and Egyptian and Latin, eating knowledge, consuming wisdom, leaving nothing behind but a Roman victory and a thick layer of ash.

Imhotep woke, which was a surprise. Surely they couldn’t have survived that inferno! He was still lying with his Roman, under the cloak Imhotep’s father had woven for him. But there was no sound or heat outside the shelter of the cloth.

He lifted one corner and exclaimed, ‘Isis! Hail, Lady, Keeper of the Door of the Underworld!’

‘If you wish,’ replied the tall, elegant, onlooker. He had a golden aura around his curly head, a white robe and long, white wings.

Strange, thought Imhotep, Isis is supposed to be a Goddess. This is a God of some sort. I don’t recognise him. And I know all of the Ennead.

‘Are you Thanatos?’ croaked Marcus Corvinus, waking and leaning on his Egyptian’s shoulder. Odd, he thought, Thanatos, God of Death, is supposed to be a dark angel.

‘I can be Thanatos if you require,’ replied the figure. His voice was even and musical. And patient.

‘We died, didn’t we? In the fire?’ reasoned Imhotep. ‘I didn’t think we could survive that, Marcus.’

‘No, ’Hotep, we evidently didn’t survive. And, if you would be so good, Honoured Celestial Being,’ Marcus and Imhotep levered themselves to their feet, creaking in every muscle, ‘I regret that I have no sacrifice to offer, but could you tell us where we are?’

‘This is The Library,’ replied the God. ‘And I am the Library Angel. Come along, now, you need to bathe, and then there will be a feast in your honour.’

‘A feast?’ asked Imhotep, following the angel, an arm around Marcus’ waist as the Roman’s was around his shoulders.

‘Well, of course,’ said the angel. ‘You saved the Treatise on Surgery and the Homeric Hymns. Naturally there would be a feast. Here is the bath. Someone will come with some refreshments and some clothes, if you would like to wear them. Then you may rest until I come to fetch you. People find the transition tiring, when it has been so,’ the angel shuddered, ‘violent.’

Marcus and Imhotep staggered into the bath. It was a series of large, steamy, tiled and painted rooms, where they were immediately surrounded by a crowd of nude boys and girls who stripped off the burned remains of Imhotep’s cloth and sat them down on chairs to be scrubbed with a strange substance which foamed; and tasted, when Marcus tried it, very flat and unpleasant. But it smelt divine, of the cypress trees at the Serapeum, the Daughter Library where the remainder of the scrolls should be safe.

The bath creatures – Imhotep observed that they had little wings, which sufficed to lift them a few cubits above the ground – washed them very thoroughly, humming and singing to themselves in a manner reminiscent of bees. They gave off harmony, a sense of happiness and a sweet scent, like honey. But they did not speak.

When Imhotep and Marcus Tullius Corvinus were rinsed as clean as the newborn, the humming attendants ushered them out of the washing room and conducted them down the steps into a sumptuous bath, into warm water which was so mineral rich that they were buoyed up. Marcus caught Imhotep’s hand and they floated together, linked, staring up at a ceiling which was made of immeasurable space, powdered by a million stars.

‘I don’t hurt anymore,’ commented Marcus. ‘All those little burns and bruises are gone. And you, my devout scholar?’

‘Yes, I feel completely unharmed. Is this your afterlife?’ asked Imhotep. ‘If so, it was very kind of you to invite me to come with you. It’s lovely.’

Marcus shivered and pulled Imhotep into the curve of his body.

‘No, my afterlife is both tedious and frightening. Not a good place at all. And to test the hypothesis, in my afterlife you can’t remember what it was to be alive. And I remember everything.’

‘So do I. This isn’t the Field of Reeds either, though don’t think I’m complaining. And did you recognise the Library Angel? And those little winged children?’

‘No, I haven’t studied much comparative religion,’ replied Marcus. ‘But you’ll stay with me? You don’t want to leave me to go to the Field of Reeds?’

‘I’ll stay,’ promised Imhotep. He relaxed in the warm water, feeling the ache of his loss dissolving in the water. ‘I would not be able to go there, anyway. My body must have been burned to ash in the fire; no mummified body, no Field of Reeds.’

‘That seems unjust,’ commented Marcus. ‘I think I like this afterlife better than either.’

‘Yes. And, do you know, Marcus, even though I’m definitely dead, I’m hungry and thirsty. Can we get out and find some of those refreshments of which the angel spoke?’

‘An excellent notion,’ replied Marcus.

The refreshments were a fine loaf of wheat bread, a plait of honey-poppyseed cake, several cheeses, a variety of fruits and a large jug of wine. Marcus looked around for a mixing bowl and a water jug, did not find them, tasted, and smiled. He filled two cups.

‘This is wonderful,’ he said to Imhotep, as they sat on a pile of pillows on a warm wooden floor in a hall hung with tapestries. ‘It would be a crime to dilute it. Drink with me?’ he asked, looking into the Egyptian’s dark eyes. ‘I don’t know how long this is going to last, if we’re dreaming so as not to feel the fire, but I want to eat and drink, and then I want to make love with you, most beautiful of scholars. Before the spell changes. Before it all turns to ash.’

‘Yes,’ agreed Imhotep, biting into a red fruit which trickled juice down his chin. Marcus leaned forward and licked it up. It tasted wonderful. ‘But this has a more permanent feeling than a dream. This is certainly a Heavenly fruit,’ he said. ‘This is nectar and ambrosia, and I would make love to you for all the time there is, until the ending of the world.’

They lay together gently, slowly, not altogether believing that each touch was real. They mouthed the divine grapes, sucking sweet juice from each other’s skin, kissing through an aeon, caressing and holding. Each caress seemed to be magnified, their skin sensitised by the cleansing, and when they cried out together the winged attendants heard, and sent up a humming paean of joy.

Marcus laughed, looking down into Imhotep’s face. He kissed him. Imhotep tasted of grapes and flowers.

‘If it all ceases, and we go into the dark,’ he told his fellow scholar, ‘it will have been worth dying to embrace you.’

‘I love you, Marcus. I treasure your love. And I saved the Treatise on Surgery, and you saved the Homeric Hymns, so it was worth our lives.’

‘It was,’ agreed Marcus. ‘But I had not expected such an extravagant reward.’

Imhotep kissed him again.

Marcus elected for a tunic and Imhotep for a cloth, and they were conducted to the feast by the Library Angel. The hall was like none they had ever seen, huge and noisy, with lot of tables and chairs and hundreds of scholars, all talking and drinking and disputing. And a group of them, in one corner, were singing.

‘I present them to you,’ announced the Angel, and the room fell silent. ‘Marcus Tullius Corvinus and Imhotep, who died in saving the Homeric Hymns and the Treatise on Surgery. The hymns inspired poets through all ages, and the Treatise educated a thousand years of healers. Hail!’ cried the Angel, and the whole company surged to their feet and cried, ‘Hail!’

‘And who’s that?’ asked Marcus of their table-mate, Captain Elijah Raven, a grizzled old man who had smuggled Ancient Greek manuscripts out of Romanian monasteries just ahead of another purge of literature. He had one leg and a parrot called Livy on his shoulder, and Marcus liked him instantly.

‘That’s Pan Tzu,’ said the Captain. ‘He carved the Analects of Confucius on stones and laid ’em face down in a path, so that after the Tiger of Ch’in was dead, philosophy could emerge again. That’s Hypatia, martyred for learning, what they forbad to women. And all them women over there, they’re witches, what wrote down their spells and recipes so other women didn’t die. And burned for it. Good earthy company for a man like me, them witches. The singers, they’re bards and troubadours; they remembered what couldn’t be written down. The women over there are the storytellers – they remembered tales that would have died out, if they hadn’t told ’em to the childer. The ones in them puffy breeks, they’re Shakespeare and his pals. I like Will. He said he’s here to improve his Greek. That chatty bloke, that’s Sir Thomas Browne, who wrote the Bibliographica Abscondita, making people look for old books, and that’s Mr Cotton, who bought ’em when I brung ’em. Nice old man, used to give me brandy, I used to bring ’im them fruits done up in sugar, not a tooth to ’is head but one and that was ’is sweet tooth, poor man. That’s Keats, who died for ’is verse, and that’s... oh, you’ll meet ‘em all, good fellows, most of ‘em. Have some beer?’

‘Do we stay here forever?’ asked Imhotep.

‘Forever and a day, my son,’ said the Captain, ‘as long as you want to be ’ere. All the lost books are in the library. If you saved a book, and you work on it, then someone in the world below will be inspired by your work. Everything we do here has its reflection in the world. Aye, somewhere some student is reading your hymns, boy, and will write a novel with a new translation that will set another soul afire. As above, so below, that’s what Master Josephus says. What more could you want? Food’s good, ale’s better. You’ve got your lover, Marcus, and your work. And if you study too much, if you tire of learning, they’ll hale you out, to fly into the stars, or bask on a beach with blue sand or bathe in the light of three moons. Universe’s your oyster. There’s a lot of advantage in being dead, I find,’ confided the Captain. His parrot Livy croaked an assent and beaked a fig, spitting the stalk down the Captain’s shirt collar.

Marcus embraced Imhotep and surveyed the gathering. ‘Yes,’ he said. ‘What do you say, my heart?’

‘Yes,’ replied Imhotep. A wealth, a treasury, of books awaited them. He felt light headed with joy. ‘More wine, my love?’